Scotia

Scotia is a Latin placename derived from Scoti, a Latin name for the Gaels,[1] first attested in the late 3rd century.[1] From the 9th century, its meaning gradually shifted, so that it came to mean only the part of Britain lying north of the Firth of Forth: the Kingdom of Scotland.[1] By the later Middle Ages it had become the fixed Latin term for what in English is called Scotland. The Romans referred to Ireland as "Scotia" around 500 A.D.

Etymology and derivations

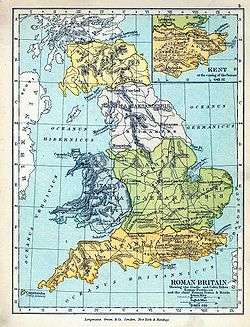

The name of Scotland is derived from the Latin Scotia: the tribe name Scoti applied to all Gaels.[2][3] The word Scoti (or Scotti) was first used by the Romans. It is found in Latin texts from the 4th century describing an Irish group which raided Roman Britain.[4] It came to be applied to all the Gaels. It is not believed that any Gaelic groups called themselves Scoti in ancient times, except when writing in Latin.[4] Old Irish documents use the term Scot (plural Scuit) going back as far as the 9th century, for example in the glossary of Cormac mac Cuilennáin.[5]

Oman derives it from Scuit, meaning someone cut-off. He believed it referred to bands of outcast Gaelic raiders, suggesting that the Scots were to the Gaels what the Vikings were to the Norse.[6][7]

The 19th century author Aonghas MacCoinnich of Glasgow proposed that Scoti was derived from a Gaelic ethnonym (proposed by MacCoinnich) Sgaothaich from sgaoth "swarm", plus the derivational suffix -ach (plural -aich)[8] However, this proposal to date has not been met with any response in mainstream place-name studies. Pope Leo X (1513–1521) decreed that the use of the name Scotia be confined to referring to land that is now Scotland.[9][10]

Virtually all names for Scotland are based on the Scotia root (cf. Dutch Schotland, French Écosse, Czech Skotsko, Zulu IsiKotilandi, Māori Koterana, Hakka Sû-kak-làn, Quechua Iskusya, Turkish İskoçya etc.), either directly or via intermediate languages. The only exceptions are the Celtic languages where the names are based on the Alba root, e.g. Manx Nalbin, Welsh Yr Alban", Irish "Albain."

Medieval usage

Scotia was a way of saying "Land of the Gaels" ; compare Angli and Anglia; Franci and Francia; Romani and Romania; etc. It originally was used as a name for Ireland, for example in Adomnán's Life of Columba,[1] and when Isidore of Seville in 580 CE writes "Scotia and Hibernia are the same country" (Isidore, lib. xii. c. 6), but the connotation is still ethnic. This is how it is used, for instance, by King Robert I of Scotland (Robert the Bruce) and Domhnall Ua Néill during the Scottish Wars of Independence, when Ireland was called Scotia Maior (greater Scotia) and Scotland Scotia Minor (lesser Scotia).

After the 11th century, Scotia was used mostly for the kingdom of Alba or Scotland, and in this way became the fixed designation. As a translation of Alba, Scotia could mean both the whole kingdom belonging to the King of Scots, or just Scotland north of the Forth.

Pope Leo X of the Roman Catholic Church eventually granted Scotland exclusive right over the word, and this led to Anglo-Scottish takeovers of continental Gaelic monasteries (e.g. the Schottenklöster).

In Irish sources

In Geoffrey Keating's Foras Feasa ar Éirinn, Ireland's ninth appellation, named it Scotia, likewise based from the sons of Milesius's of whom's mother's name, Scota, who was the daughter of Pharaoh Nectanebo I, king of Egypt; or perhaps from themselves, they being originally of the Scythian race." According to the Middle Irish language synthetic history Lebor Gabála Érenn she was the daughter of Pharaoh Necho II of Egypt. Other sources say that Scota was the daughter of Pharaoh Neferhotep I of Egypt and his wife Senebsen, and was the wife of Míl, that is Milesius, and the mother of Éber Donn and Érimón. Míl had given Neferhotep military aid against ancient Ethiopia and was given Scota in marriage as a reward for his services. Writing in 1571, Edmund Campion named the pharaoh Amenophis; Keating named him Cincris.

Other uses

In geography, the term is also used for the following:

- the Canadian province of Nova Scotia (New Scotland)

- the village of Scotia in New York State

- the Scotia-Glenville High School in New York State named after a Scottish settler

- the Scotia Sea between Antarctica and South America

- the Scotia Plate, a tectonic plate located to the south of South America

The term also is used/for the following purposes;

- to describe a piece of wood millwork that is used at the base of columns and in stair construction

- Scotiabank, a trade name for the Bank of Nova Scotia

- (rarely) as a feminine first name

- Pride Scotia, Scotland's national LGBT pride festival, involving a march and a community based festival held in June

See also

- Scota

- Scotia's Grave, in the hills, just south of Tralee, County Kerry

- Scottish Gaelic

- Caledonia

References

- Duffy, Seán. Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. Routledge, 2005. p.698

- https://www.tcd.ie/news_events/articles/crowning-of-irelands-last-scottish-high-king/

- "The Story of the Irish Race". Homepage.eircom.net. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- Meyer, K. (ed.). Sanas Cormaic: an Old-Irish Glossary compiled by Cormac úa Cuilennáin, King-Bishop of Cashel in the ninth century. Dil.ie. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- C. Oman, A History of England before the Norman Conquest, London, 1910, p. 157.

- Sir Charles Oman: A History of England before the Norman Conquest

- MacCoinnich, Aonghas Eachdraidh na h-Alba (Glasgow 1867)

- "Scotia, my Scotia, or bringing back the real Scotland!!". Reformation.org. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- Benedict's Fitzpatrick's Ireland and the Foundations of Europe, pp. 376-379