Vaikom Muhammad Basheer

Vaikom Muhammad Basheer (21 January 1908 – 5 July 1994), fondly known as Beypore Sultan, was an Indian independence activist and writer of Malayalam literature . He was a writer, humanist, freedom fighter, novelist and short story writer, noted for his path-breaking, down-to-earth style of writing that made him equally popular among literary critics as well as the common man. His notable works include Balyakalasakhi, Shabdangal, Pathummayude Aadu, Mathilukal, Ntuppuppakkoranendarnnu, Janmadinam and Anargha Nimisham and the translations of his works into other languages have earned him worldwide acclaim. The Government of India awarded him the fourth highest civilian honour of the Padma Shri in 1982. He was also a recipient of the Sahitya Academy Fellowship, Kerala Sahitya Academy Fellowship, and the Kerala State Film Award for Best Story.

Vaikom Muhammad Basheer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Abdul Rahman Muhammad Basheer[1] 21 January 1908 Thalayolaparambu, Vaikom, Kottayam district, Travancore |

| Died | 5 July 1994 (aged 86) Beypore, Calicut district, Kerala, India |

| Occupation | Author, freedom fighter |

| Language | Malayalam |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Genre | Novel, short story, essays, memoirs |

| Notable works | Balyakalasakhi; Pathummayude Aadu |

| Notable awards | |

| Spouse | Fathima Basheer (Fabi) |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives |

|

Biography

Early life

Basheer was born on January 21, 1908 [2][3] in Thalayolaparambu (near Vaikom) Kottayam District, to Kayi AbduRahman, a timber merchant, and his wife, Kunjathumma,[4] as their eldest child.[5] After completing his primary education at a local Malayalam medium school, he joined an English medium school in Vaikom, five miles away, for higher education. It was during this time, he met Mahatma Gandhi, when the Indian independence movement leader came to Vaikom for the satyagraha, which later came to be known as Vaikom Satyagraham, and became his follower. He started wearing Khādī, inspired by the swadeshi ideals of Gandhi.[6] Basheer would later write about his experiences on how he managed to climb on to the car in which Gandhi was traveling and touched his hand.[4]

Freedom struggle involvement

He resolved to join the fight for an Indian Independence, leaving school to do so while he was in the fifth form.[6] Basheer was known for his secular attitude, and he treated all religions with respect. Since there was no active independence movement in Kochi – being a princely state – he went to Malabar district to take part in the Salt Satyagraha in 1930.[7] His group was arrested before they could participate in the satyagraha. Basheer was sentenced to three months imprisonment and sent to Kannur Prison. He became inspired by stories of heroism by revolutionaries like Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev Thapar and Shivaram Rajguru, who were executed while he was in the jail. His release, along with 600 of his fellow prisoners, came in March 1931 following the Gandhi-Irwin pact. Once free, he organised an anti-British movement and edited a revolutionary journal, Ujjivanam, because of which an arrest warrant was issued on him and he left Kerala.[8]

Journey

Having left Kerala, he embarked upon a long journey that took him across the length and breadth of India and to many places in Asia and Africa for seven years, doing whatever work that seemed likely to keep him from starvation.[8] His occupations ranged from that of a loom fitter, fortune teller, cook, newspaper seller, fruit seller, sports goods agent, accountant, watchman, shepherd, hotel manager to living as an ascetic with Hindu saints and Sufi mystics in their hermitages in Himalayas and in the Ganges basin, following their customs and practices, for more than five years. There were times when, with no water to drink, without any food to eat, he came face to face with death.[4]

After doing menial jobs in cities such as Ajmer, Peshawar, Kashmir and Calcutta, Basheer returned to Ernakulam in the mid-1930s. While trying his hands at various jobs, like washing vessels in hotels, he met a manufacturer of sports goods from Sialkot who offered him an agency in Kerala. And Basheer returned home to find his father's business bankrupt and the family impoverished. He started working as an agent for the Sialkot sports company at Ernakulam, but lost the agency when a bicycle accident incapacitated him temporarily.[9] On recovering, he resumed his endless hunt for jobs. He walked into the office of a newspaper Jayakesari whose editor was also its sole employee. He did not have a position to offer, but offered to pay money if Basheer wrote a story for the paper.[10] Thus Basheer found himself writing stories for Jayakesari and it was in this paper that his first story "Ente Thankam" (My Darling) was published in the year 1937. A path-breaker in Malayalam romantic fiction, it had its heroine a dark-complexioned hunchback.[11] His early stories were published between 1937 and 1941 in Navajeevan, a weekly published in Trivandrum in those days.[12]

Imprisonment and after

At Kottayam (1941–42), he was arrested and put in a police station lock-up, and later shifted to another lock up in Kollam Kasba police station.[8] The stories he heard from policemen and prisoners there appeared in later works, and he wrote a few stories while at the lock-up itself. He spent a long time in lock-up awaiting trial, and after trial was sentenced to two years and six months imprisonment. He was sent to Thiruvananthapuram central jail. While at jail, he forbade M. P. Paul from publishing Balyakalasakhi. He wrote Premalekhanam (1943) while serving his term and published it on his release. Baalyakaalasakhi was published in 1944 after further revisions, with an introduction by Paul.[13] M. K. Sanu, critic and a friend of Basheer, would later say that M. P. Paul's introduction contributed significantly in developing his writing career.[14] He then made a career as a writer, initially publishing the works himself and carrying them to homes to sell them. He ran two bookstalls in Ernakulam; Circle Bookhouse and later, Basheer's Bookstall. After Indian independence, he showed no further interest in active politics, though concerns over morality and political integrity are present all over his works.[4]

Basheer got married in 1958 when he was over forty eight years old and the bride, Fathima, fondly called by Basheer as Fabi (combining the first syllables of Fathima and Basheer), was twenty years of age.[15] The couple had a son, Anees and a daughter, Shahina, and the family lived in Beypore, on the southern edge of Kozhikode.[16] During this period he also suffered from mental illness and was twice admitted to mental sanatoriums.[17] He wrote one of his most famous works, Pathummayude Aadu (Pathumma's Goat), while undergoing treatment in a mental hospital in Thrissur. The second spell of paranoia occurred in 1962, after his marriage when he had settled down at Beypore. He recovered both times, and continued his writings.[18]

Basheer, who earned the sobriquet, Beypore Sultan, after he wrote about his later-day life in Beypore as a Sultan,[8] died there, on July 5, 1994, at the age of 84, survived by his wife and children.[17] Fabi Basheer outlived him for over two decades and died on July 15, 2015, at the age of 77, succumbing to complications following a pneumonia attack.[15]

Legacy

Language

Basheer is known for his unconventional style of language.[19] He did not differentiate between literary language and the language spoken by the commons[20] and did not care about the grammatical correctness of his sentences. Initially, even his publishers were unappreciative of the beauty of this language; they edited out or modified conversations. Basheer was outraged to find his original writings transcribed into "standardised" Malayalam, devoid of freshness and natural flow, and he forced them to publish the original one instead of the edited one. Basheer's brother Abdul Khader was a Malayalam teacher. Once while reading one of the stories, he asked Basheer, "where are aakhyas and aakhyathas (elements of Malayalam grammar) in this...?". Basheer shouted at him saying that "I am writing in normal Malayalam, how people speak. and you don't try to find your stupid 'aakhya and aakhyaada' in this"!. This points out to the writing style of Basheer, without taking care of any grammar, but only in his own village language. Though he made funny remarks regarding his lack of knowledge in Malayalam, he had a very thorough knowledge of it.

Basheer's contempt for grammatical correctness is exemplified by his statement Ninte Lodukkoos Aakhyaadam! ("Your 'silly stupid' grammar!") to his brother, who sermonises him about the importance of grammar (Pathummayude Aadu).[21]

Themes

Basheer's characters were also marginalised people like gamblers, thieves, pickpockets and prostitutes, and they appeared in his works, naive and pure.[9] An astute observer of human character, he skilfully combined humour and pathos in his works. Love, hunger and poverty, life in prison are recurring themes in his works. There is enormous variety in them – of narrative style, of presentation, of philosophical content, of social comment and commitment. His association with India's independence struggle, the experiences during his long travels and the conditions that existed in Kerala, particularly in the neighbourhood of his home and among the Muslim community – all had a major impact on them. Politics and prison, homosexuality, all were grist to his mill. All of Basheer's love stories have found their way into the hearts of readers; perhaps no other writer has had such an influence on the way Malayalis view love. The major theme of all Basheer stories is love and humanity. In the story Mucheettukalikkarante Makal (The Card sharp's Daughter), when Sainaba comes out of the water after stealing his bananas, Mandan Muthappa says only one thing: "Sainaba go home and dry your hair else you may fall sick." This fine thread of humanism can be experienced in almost all his stories.[22]

About the influence of Western literature in his works, Basheer once wrote: "I can readily say that I have not been influenced by any literature, Western or Eastern, for, when I started writing I had no idea of literature. Even now it is not much different. It is only after I had written quite a bit, that I had opportunities to contact Western literature. I read all that I could get hold of—Somerset Maugham, Steinbeck, Maupassant, Flaubert, Romain Rolland, Gorky, Chekhov, Hemingway, Pearl S. Buck, Shakespeare, Galsworthy, Shaw... In fact, I organised one or two bookstalls so that I could get more books to read. But I read these books mainly to know their craft. I myself had plenty of experience to write about! I have even now! I am unable to ascertain who has influenced me. Perhaps Romain Rolland and Steinbeck—but even they, not much."[23]

Works

Almost all of Basheer's writing can be seen as falling under the heading of prose fiction – short stories and novels, though there is also a one-act play and volumes of essays and reminiscences. Basheer's fiction is very varied and full of contrasts. There are poignant situations as well as merrier ones – and commonly both in the same narrative. There are among his output realistic stories and tales of the supernatural. There are purely narrative pieces and others which have the quality of poems in prose. In all, a superficially simple style conceals a great subtlety of expression. His works have been translated into 18 languages.[8]

His literary career started off with the novel Premalekhanam, a humorous love story between Keshavan Nair – a young bank employee, an upper caste Hindu (Nair) – and Saramma – an unemployed Christian woman. Hidden underneath the hilarious dialogues we can see a sharp criticism of religious conservatism, dowry and similar conventions existing in society. The film adaptation of the story was by P. A. Backer in 1985, with the lead roles played by Soman and Swapna.[24] It was remade again by Aneesh Anwar in 2017, featuring Farhaan Faasil, Joy Mathew and Sheela.[25]

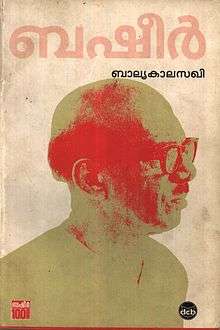

Premalekhanam was followed by the novel Balyakalasakhi – a tragic love story between Majeed and Suhra – which is among the most important novels in Malayalam literature[26] in spite of its relatively small size (75 pages), and is commonly agreed upon as his magnum opus work.[27] In his foreword to Balyakalasakhi, Jeevithathil Ninnum Oru Aedu (A Page From Life), M. P. Paul brings out the beauty of this novel, and how it is different from run-of-the-mill love stories. The novel was later adapted into a film by Sasikumar, under the same name.[28] It was again remade with the same title in 2014, by Pramod Payyannur,[29] with Mammootty and Isha Talwar playing the lead.[30]

The autobiographical Janmadinam ("Birthday", 1945) is about a writer struggling to feed himself on his birthday.[31] While many of the stories present situations to which the average reader can easily relate, the darker, seamier side of human existence also finds a major place, as in the novel Shabdangal ("Voices", 1947),[32] which faced heavy criticism for violence and vulgarity.[33]

Ntuppuppakkoranendarnnu ("My Gran'dad 'ad an Elephant", 1951) is a fierce attack on the superstitious practices that existed among Muslims. Its protagonist is Kunjupathumma, a naive, innocent and illiterate village belle. She falls in love with an educated, progressive, city-bred man, Nisaar Ahamed. Illiteracy is fertile soil for superstitions, and the novel is about education enlightening people and making them shed age-old conventions. Velichathinentoru Velicham (a crude translation can be "What a bright brightness!") one of the most quoted Basheer phrases occurs in Ntuppuppaakkoraanaendaarnnu. People boast of the glory of days past, their "grandfather's elephants", but that is just a ploy to hide their shortcomings. The book was later translated into English by R. E. Asher.[34]

His next novel was Pathummayude Aadu, an autobiographical work published in 1959, featuring mostly his family members.[35] The book tells the story of everyday life in a Muslim family.[36] Mathilukal (Walls) deals with prison life in the pre-independence days. It is a novel of sad irony set against a turbulent political backdrop. The novelist falls in love with a woman sentenced for life who is separated from him by insurmountable walls. They exchange love-promises standing on two sides of a wall, only to be separated without even being able to say good-bye. Before he "met" Naraayani, the loneliness and restrictions of prison life was killing Basheer; but when the orders for his release arrive he loudly protests, "Who needs freedom? Outside is an even bigger jail." The novel was later made into a film with same name by Adoor Gopalakrishnan with Mammootty playing Basheer.[37]

Sthalathe Pradhana Divyan, Anavariyum Ponkurishum, Mucheettukalikkarante Makal and Ettukali Mammoonju featured the life of real life characters in his native village of Thalayolaparambu (regarded as Sthalam in these works). Perch, a Chennai based theatre, has adapted portions from Premalekhanam and Mucheettukalikkarante Makal as a drama under the title, ;;The Moonshine and the Sky Toffee.[38]

Trivia

New application on Basheer named Basheer Malayalathinte Sultan is now available as an iPad application which includes eBooks of all the works of the author, animation of his prominent works like Pathumayude Aadu, Aanapuda, audio book, special dictionaries encloses words used by Basheer, sketches of characters made by renowned artistes and rare photos among others.[39] Fabi Basheer published her memoirs, Basheerinte Ediye,[40] which details her life with her husband.[41]

Awards and honours

Sahitya Akademi honoured Basheer with their fellowship in 1970,[42] the same year as he was honoured with the distinguished fellowship by the Kerala Sahitya Akademi.[43] The Government of India awarded him the fourth highest civilian honour of the Padma Shri in 1982[44] and five years later, the University of Calicut conferred on him the honorary degree of the Doctor of Letters on January 19, 1987.[45] He received the Kerala State Film Award for Best Story for the Adoor Gopalakrishnan film, Mathilukal in 1989[46] and the inaugural Lalithambika Antharjanam Award in 1992[47] followed by the Prem Nazir Award the same year.[21] He received two awards in 1993, the Muttathu Varkey Award[48] and the Vallathol Award.[49][50] The Thamrapathra'of the Government of India (1972), Abu Dhabi Malayala Samajam Literary Award (1982), Samskaradeepam Award (1987) and Jeddah Arangu Award (1994) were some of the other awards received by him.[21] Mathrubhumi issued a festschrift on him, Ormmayile Basheer (Basheer - Reminiscences) in 2003 which featured several articles and photos[51] and the India Post released a commemorative postage stamp, depicting his image, on January 21, 2009.[52][53]

Published works

Novels

She asked me nothing.

I was amazed. “How did you know, Umma, that I was coming today?”

Mother replied, “Oh... I cook rice and wait every night.”

It was a simple statement. Every night I did not turn up, but mother had kept awake waiting for me.

The years have passed. Many things have happened.

But mothers still wait for their sons.

“Son, I just want to see you...”| # | Title | Translation in English | Year of Publishing |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Premalekhanam | The Love Letter | 1943 |

| 2 | Balyakalasakhi | Childhood Companion | 1944 |

| 3 | Shabdangal | The Voices | 1947 |

| 4 | Ntuppuppakkoranendarnnu | My Grandad Had an Elephant | 1951 |

| 5 | Maranathinte Nizhalil | In the Shadow of Death | 1951 |

| 6 | Mucheettukalikkarante Makal | The Card Sharper's Daughter | 1951 |

| 7 | Sthalathe Pradhana Divyan | The Principal Divine of the Place | 1953 |

| 8 | Anavariyum Ponkurishum | Elephant Scooper and Golden Cross | 1953 |

| 9 | Jeevithanizhalppadukal | The Shadows of Life | 1954 |

| 10 | Pathummayude Aadu | Paththumma's Goat | 1959 |

| 11 | Mathilukal | Walls | 1965 |

| 12 | Thara Specials | 1968 | |

| 13 | Manthrikappoocha | The Magic Cat | 1968 |

| 14 | Prempatta | The Loving Cockroach (Published posthumously) | 2006 |

Short stories

| # | Title | Translation in English | Year of Publishing |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Janmadinam | The Birthday | 1945 |

| 2 | Ormakkurippu | Jottings from Memory | 1946 |

| 3 | Anargha Nimisham | Invaluable Moment (See "Anal Haq") | 1946 |

| 4 | Viddikalude Swargam | Fools' Paradise | 1948 |

| 5 | Pavappettavarude Veshya | The Prostitute of the Poor | 1952 |

| 6 | Vishwavikhyathamaya Mookku | The World-renowned Nose | 1954 |

| 7 | Visappu | The Hunger | 1954 |

| 8 | Oru Bhagavad Gitayum Kure Mulakalum | A Bhagavadgeetha and Some Breasts | 1967 |

| 9 | Anappooda | Elephant-hair | 1975 |

| 10 | Chirikkunna Marappava | The Laughing Wooden Doll | 1975 |

| 11 | Bhoomiyude Avakashikal | The Inheritors of the Earth | 1977 |

| 12 | Shinkidimunkan | The Fools' God Man | 1991 |

| 13 | Sarpayajnam | The Snake Ritual |

Others

| # | Title | Translation in English | Year of Publishing | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dharmarajyam | 1938 | Essays | |

| 2 | Kathabeejam | Story Seed | 1945 | Play |

| 3 | Nerum Nunayum | Truth and Lie | 1969 | Commentary and letters |

| 4 | Ormayude Arakal | The Cells of Memory | 1973 | Commentary and memoirs |

| 5 | Anuragathinte Dinangal | The Days of Desire | 1983 | Diary; Originally titled Kaamukantaey Diary [The Diary of the Paramour] and changed later on the suggestion of M. T. Vasudevan Nair |

| 6 | Bhargavi Nilayam | Bhargavi's Mansion | 1985 | Screenplay for a film (1964) by A. Vincent which is credited as the first horror cinema in Malayalam; adapted from the short story "Neelavelichcham" ["The Blue Glow"] |

| 7 | M. P. Paul | 1991 | Reminiscences of his friendship with M. P. Paul | |

| 8 | Cheviyorkkuka! Anthimakahalam | Hark! The Final Clarion-call!! | 1992 | Speech |

| 9 | Yaa Ilaahi! | Oh God! | 1997 | Collection of stories, essays, letters and poem; Published posthumously |

| 10 | Jeevitham Oru Anugraham | Life is a Blessing | 2000 | Collection of stories, essays and play; Published posthumously |

| 11 | Basheerinte Kathukal | Basheer's Letters | 2008 | Letters; Published posthumously |

Filmography

| # | Year | Title | Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1964 | Bhargavi Nilayam | Story, dialogues, screenplay |

| 2 | 1967 | Balyakalasakhi | Story, dialogues, screenplay |

| 3 | 1975 | Mucheettukalikkaarante Makal | Story |

| 4 | 1985 | Premalekhanam | Story |

| 5 | 1988 | Dhwani | Acting |

| 6 | 1990 | Mathilukal | Story |

| 7 | 1995 | Sasinas | Story |

| 8 | 2013 | Kathaveedu | Story |

| 9 | 2014 | Balyakalasakhi | Story |

| 10 | 2017 | Basheerinte Premalekhanam | Story |

References

- V. B. C. Nair (1976). "പൂര്ണ്ണത തേടുന്ന അപൂര്ണ്ണ ബിന്ദുക്കള് [Poornatha Thedunna Apoornna Bindukkal]". Malayalanadu (in Malayalam).

- "Vaikom Muhammad Basheer - Date of Birth". 18 December 2011. Archived from the original on 18 December 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "Basheer Smaraka Trust". www.basheersmarakatrust.com. 19 December 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- "Biography on Kerala Sahitya Akademi portal". Kerala Sahitya Akademi portal. 29 March 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- "Vaikom Muhammad Basheer - profile on Kerala Culture". www.keralaculture.org. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- Reddiar, Mahesh (19 March 2010). "Vaikom Muhammad Basheer - Biography". PhilaIndia.info. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "Vaikom Muhammad Basheer Veethi profile". veethi.com. 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "Vaikom Muhammad Basheer: When brevity becomes soul of wit". The Week. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- Kakanadan (8 March 2008). "Vaikom Mohammed Basheer is the true inheritor of the earth". The Economic Times. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- Madhubālā Sinhā (2009). Encyclopaedia of South Indian literature, Volume 3. Anmol Publications. p. 240.

- M. N. Vijayan (1996). M. N. Vijayan (ed.). Basheer fictions. Katha. p. 21.

- Vaikom Muhammad Basheer (1954). "Foreword". Vushappu (Hunger). Current Books.

It is years since I have started writing stories. When did I start? I think it was from 1937. I have been living in Ernakulam since then. I was a writer by profession. I wrote a great deal. I would get my writing published in newspapers and journals. No one paid me for it. The stories were published between 1937 and 1941 in Navajeevan, a weekly published in Trivandrum in those days.

- Thomas Welbourne Clark (1970). The Novel in India: Its Birth and Development. University of California Press. pp. 228–. ISBN 978-0-520-01725-2.

- "Remembering a visionary - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- July 15, Charmy Harikrishnan; July 15, 2015UPDATED; Ist, 2015 18:27. "Malayalam literature's first lady Fabi Basheer passes away". India Today. Retrieved 30 March 2019.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Musthari, Jabir (16 July 2015). "Basheer's widow breathes her last". The Hindu. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "കരിങ്കല്ലിൽ തീർത്ത മതിലുകൾ". ManoramaOnline. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "Basheer's Insanity". archives.mathrubhumi.com. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- Rath, Ramakanta (2001). "Vaikom Muhammad Basheer (article)". Indian Literature. 45 (4 (204)): 153–155. JSTOR 23344259.

- "Basheer explained complex things in common man'". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "Vaikom Muhammad Basheer Special - Mathrubhumi Books". archives.mathrubhumi.com. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "Quran, karma and a gnostic god". Times of India Blog. 20 January 2018. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- K.M.George (1972). Western Influence on Malayalam Language and Literature. Sahitya Akademi. p. 112.

- "Premalekhanam [1985]". malayalasangeetham.info. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "Joy Mathew and Sheela in Basheerinte Premalekhanam - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "ഏറ്റവും മഹത്തായ പ്രണയം ഏതായിരിക്കും?". ManoramaOnline. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "സാഹിത്യ സുല്ത്താനെ ഓര്മ്മിക്കുമ്പോള്". Mathrubhumi. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "Baalyakaalasakhi (1967)". www.malayalachalachithram.com. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- Anima, P. (31 May 2013). "Translating Basheer to the screen". The Hindu. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- Naliyath, Sunil (6 February 2014). "Poetry on reel". The Hindu. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "മനസ്സിരുത്തി വായിക്കണം ബഷീറിന്റെ ഈ കഥ". ManoramaOnline. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- Vaikkaṃ Muhammad Baṣīr (1994). Poovan Banana and the Other Stories - 1. Orient Blackswan. pp. 2–. ISBN 978-81-250-0323-6.

- Kaustav Chakraborty (17 March 2014). De-stereotyping Indian Body and Desire. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 110–. ISBN 978-1-4438-5743-7.

- "Great Keralites". www.ourkeralam.com. 29 March 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- "മാന്ത്രിക ബഷീർ". ManoramaOnline. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- Vaikkaṃ Muhammad Baṣīr (1994). Poovan Banana and the Other Stories. Orient Blackswan. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-81-250-0323-6.

- "Mathilukal (1990)". www.malayalachalachithram.com. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "ബേപ്പൂർ സുൽത്താന് ആദരമായി 'നിലാവും ആകാശമിട്ടായി'യും വീണ്ടും അരങ്ങത്തേക്ക്". ManoramaOnline. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "Basheer Malayalathinte Sultan for iPad". Download.com. 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- Basheer, Fabi (2011). Basheerinte ediye / (in Malayalam).

- "Fabi Basheer is dead - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "Sahitya Akademi: Fellows and Honorary Fellows". sahitya-akademi.gov.in. 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "Kerala Sahitya Akademi Fellowship". Kerala Sahitya Akademi. 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "Padma Awards Directory (1954-2017)" (PDF). 30 March 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "Former Honorary Degree Recipients" (PDF). University of Calicut. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- "State Film Awards 1969 – 2011". Public Relations Department, Government of Kerala. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- "Lalithambika Antharjanam Smaraka Sahitya Award". www.keralaculture.org. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "മുട്ടത്ത്വര്ക്കി പുരസ്കാരം" [Muttathu Varkey Award]. Mathrubhumi (in Malayalam). 17 September 2010. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- "വള്ളത്തോള് പുരസ്കാരം" [Vallathol Award]. Mathrubhumi (in Malayalam). 17 September 2010. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- "Winners of Vallathol Literary Awards". www.keralaculture.org. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "Ormmayile Basheer". archives.mathrubhumi.com. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "Commemorative and definitive stamps". postagestamps.gov.in. 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "WNS: IN002.09 (Vaikom Muhhammad Busheer)". Universal Postal Union. 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "Basheer and the freedom struggle". frontline.thehindu.com. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

Further reading

- Ronald E. Asher (24 January – 6 February 1998). "Basheer and the freedom struggle". Frontline. 15 (2).

- V. Abdulla (12 August 1994). "A lone traveller". Frontline.

- K. Satchidanandan (19 January – 1 February 2008). "Sultan of story: A birth centenary tribute to Vaikom Mohammed Basheer who picked up his tales from life's poetry". Frontline. 25 (2).

- Venu Menon. "Pantheon Revisited". Venumenon.com.

- Rafi, N. V. Muhammad (8 June 2010). "Ecopresence in the novels of Vaikom Muhammad Basheer". University. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- Satchidanandan, K. (2009). "Vaikom Muhammad Basheer and Indian Literature". Indian Literature. 53 (1 (249)): 57–78. JSTOR 23348483.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vaikom Muhammad Basheer. |

- "List of Works by Vaikom Muhammad Basheer". Kerala Sahitya Akademi. 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- Vaikom Muhammad Basheer on IMDb

- "Portrait commissioned by Kerala Sahitya Akademi". Kerala Sahitya Akademi. 29 March 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- Kerala DD News (15 July 2015). "Vaikom Muhammad Basheer- A profile". YouTube. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- Ramki M (23 June 2011). "Vaikom Muhammad Basheer - A presentation". slideshare.net. Retrieved 30 March 2019.