Sannyasa

Sannyasa (Sanskrit: संन्यास; IAST: Saṃnyāsa) is the life stage of renunciation within the Hindu philosophy of four age-based life stages known as ashramas, with the first three being Brahmacharya (bachelor student), Grihastha (householder) and Vanaprastha (forest dweller, retired).[1] Sannyasa is traditionally conceptualized for men or women in late years of their life, but young brahmacharis have had the choice to skip the householder and retirement stages, renounce worldly and materialistic pursuits and dedicate their lives to spiritual pursuits.

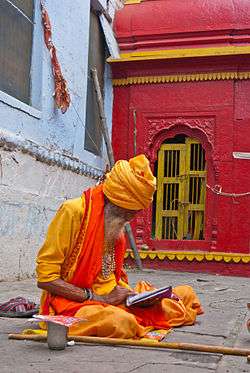

Sannyasa is a form of asceticism, is marked by renunciation of material desires and prejudices, represented by a state of disinterest and detachment from material life, and has the purpose of spending one's life in peaceful, love-inspired, simple spiritual life.[2][3] An individual in Sanyasa is known as a Sannyasi (male) or Sannyasini (female) in Hinduism,[note 1] which in many ways parallel to the Sadhu and Sadhvi traditions of Jain monasticism, the bhikkhus and bhikkhunis of Buddhism and the monk and nun traditions of Christianity.[5]

Sannyasa has historically been a stage of renunciation, ahimsa (non-violence) peaceful and simple life and spiritual pursuit in Indian traditions. However, this has not always been the case. After the invasions and establishment of Muslim rule in India, from the 12th century through the British Raj, parts of the Shaiva(Gossain) and Vaishnava(Bairagi) ascetics metamorphosed into a military order, where they developed martial arts, created military strategies, and engaged in guerrilla warfare.[6] These warrior sanyasi (ascetics) played an important role in helping European colonial powers establish themselves in the Indian subcontinent.[7]

Etymology and synonyms

Saṃnyāsa in Sanskrit nyasa means purification, sannyasa means "Purification of Everything".[8] It is a composite word of saṃ- which means "together, all", ni- which means "down" and āsa from the root as, meaning "to throw" or "to put".[9] A literal translation of Sannyāsa is thus "to put down everything, all of it". Sannyasa is sometimes spelled as Sanyasa.[9]

The term Saṃnyasa makes appearance in the Samhitas, Aranyakas and Brahmanas, the earliest layers of Vedic literature (2nd millennium BCE), but it is rare.[10] It is not found in ancient Buddhist or Jaina vocabularies, and only appears in Hindu texts of the 1st millennium BCE, in the context of those who have given up ritual activity and taken up non-ritualistic spiritual pursuits discussed in the Upanishads.[10] The term Sannyasa evolves into a rite of renunciation in ancient Sutra texts, and thereafter became a recognized, well discussed stage of life (Ashrama) by about the 3rd and 4th century CE.[10]

Sanyasis are also known as Bhiksu, Pravrajita/Pravrajitā,[11] Yati,[12] Sramana and Parivrajaka in Hindu texts.[10]

History

Jamison and Witzel state[13] early Vedic texts make no mention of Sannyasa, or Ashrama system, unlike the concepts of Brahmacharin and Grihastha which they do mention.[14] Instead, Rig Veda uses the term Antigriha (अन्तिगृह) in hymn 10.95.4, still part of extended family, where older people lived in ancient India, with an outwardly role.[13] It is in later Vedic era and over time, Sannyasa and other new concepts emerged, while older ideas evolved and expanded. A three-stage Ashrama concept along with Vanaprastha emerged about or after 7th Century BC, when sages such as Yājñavalkya left their homes and roamed around as spiritual recluses and pursued their Pravrajika (wanderer) lifestyle.[15] The explicit use of the four stage Ashrama concept, appeared a few centuries later.[13][16]

However, early Vedic literature from 2nd millennium BC, mentions Muni (मुनि, monks, mendicants, holy man), with characteristics that mirror those found in later Sannyasins and Sannyasinis. Rig Veda, for example, in Book 10 Chapter 136, mentions munis as those with Kesin (केशिन्, long haired) and Mala clothes (मल, soil-colored, yellow, orange, saffron) engaged in the affairs of Mananat (mind, meditation).[17] Rigveda, however, refers to these people as Muni and Vati (वति, monks who beg).

केश्यग्निं केशी विषं केशी बिभर्ति रोदसी । केशी विश्वं स्वर्दृशे केशीदं ज्योतिरुच्यते ॥१॥ मुनयो वातरशनाः पिशङ्गा वसते मला । वातस्यानु ध्राजिं यन्ति यद्देवासो अविक्षत ॥२॥

He with the long loose locks (of hair) supports Agni, and moisture, heaven, and earth; He is all sky to look upon: he with long hair is called this light. The Munis, girdled with the wind, wear garments of soil hue; They, following the wind's swift course, go where the Gods have gone before.

— Rig Veda, Hymn 10.CXXXVI.1-2[17]

These Munis, their lifestyle and spiritual pursuit, likely influenced the Sannyasa concept, as well as the ideas behind the ancient concept of Brahmacharya (bachelor student). One class of Munis were associated with Rudra.[18] Another were Vratyas.

Lifestyle and goals

Hinduism has no formal demands nor requirements on the lifestyle or spiritual discipline, method or deity a Sanyasin or Sanyasini must pursue – it is left to the choice and preferences of the individual.[19] This freedom has led to diversity and significant differences in the lifestyle and goals of those who adopt Sannyasa. There are, however, some common themes. A person in Sannyasa lives a simple life, typically detached, itinerant, drifting from place to place, with no material possessions or emotional attachments. They may have a walking stick, a book, a container or vessel for food and drink, often wearing yellow, saffron, orange, ochre or soil colored clothes. They may have long hair and appear disheveled, and are usually vegetarians.[19] Some minor Upanishads as well as monastic orders consider women, children, students, fallen men (those with a criminal record) and others as not qualified to become Sannyasa; while other texts place no restrictions.[20] The dress, the equipage and lifestyle varies between groups. For example, Sannyasa Upanishad in verses 2.23 to 2.29, identifies six lifestyles for six types of renunciates.[21] One of them is described as living with the following possessions,[22]

Pot, drinking cup and flask – the three supports, a pair of shoes,

a patched robe giving protection – in heat and cold, a loin cloth,

bathing drawers and straining cloth, triple staff and coverlet.— Sannyasa Upanishad, 1.4[22]

Those who enter Sannyasa may choose whether they join a group (mendicant order). Some are anchorites, homeless mendicants preferring solitude and seclusion in remote parts, without affiliation.[23] Others are cenobites, living and traveling with kindred fellow-Sannyasi in the pursuit of their spiritual journey, sometimes in Ashramas or Matha/Sangha (hermitages, monastic order).[23]

Most Hindu ascetics adopt celibacy when they begin Sannyasa. However, there are exceptions, such as the Saiva Tantra school of asceticism where ritual sex is considered part of liberation process.[24] Sex is viewed by them as a transcendence from a personal, intimate act to something impersonal and ascetic.[24]

The goal

The goal of the Hindu Sannyasin is moksha (liberation).[25][26] The idea of what that means varies from tradition to tradition.

Who am I, and in what really do I consist? What is this cage of suffering?

For the Bhakti (devotion) traditions, liberation consists of union with the Divine and release from Saṃsāra (rebirth in future life);[27] for Yoga traditions, liberation is the experience of the highest Samādhi (deep awareness in this life);[28] and for the Advaita tradition, liberation is jivanmukti – the awareness of the Supreme Reality (Brahman) and Self-realization in this life.[29][30] Sannyasa is a means and an end in itself. It is a means to decreasing and then ultimately ending all ties of any kind. It is a means to the soul and meaning, but not ego nor personalities. Sannyasa does not abandon the society, it abandons the ritual mores of the social world and one's attachment to all its other manifestations.[31] The end is a liberated, content, free and blissful existence.[32][33]

The behaviors and characteristics

The behavioral state of a person in Sannyasa is described by many ancient and medieval era Indian texts. Bhagavad Gita discusses it in many verses, for example:[34]

ज्ञेयः स नित्यसंन्यासी यो न द्वेष्टि न काङ् क्षति । निर्द्वन्द्वो हि महाबाहो सुखं बन्धात्प्रमुच्यते ॥५-३॥

He is known as a permanent Sannyasin who does not hate, does not desire, is without dualities (opposites). Truly, Mahabaho (Arjuna), he is liberated from bondage.

Other behavioral characteristics, in addition to renunciation, during Sannyasa include: ahimsa (non-violence), akrodha (not become angry even if you are abused by others), disarmament (no weapons), chastity, bachelorhood (no marriage), avyati (non-desirous), amati (poverty), self-restraint, truthfulness, sarvabhutahita (kindness to all creatures), asteya (non-stealing), aparigraha (non-acceptance of gifts, non-possessiveness) and shaucha (purity of body speech and mind).[35][36] Some Hindu monastic orders require the above behavior in form of a vow, before a renunciate can enter the order.[35] Tiwari notes that these virtues are not unique to Sannyasa, and other than renunciation, all of these virtues are revered in ancient texts for all four Ashramas (stages) of human life.[37]

Baudhayana Dharmasūtra, completed by about 7th century BC, states the following behavioral vows for a person in Sannyasa[38]

These are the vows a Sannyasi must keep –

Abstention from injuring living beings, truthfulness, abstention from appropriating the property of others, abstention from sex, liberality (kindness, gentleness) are the major vows. There are five minor vows: abstention from anger, obedience towards the guru, avoidance of rashness, cleanliness, and purity in eating. He should beg (for food) without annoying others, any food he gets he must compassionately share a portion with other living beings, sprinkling the remainder with water he should eat it as if it were a medicine.

Types

Ashrama Upanishad identified various types of Sannyasi renouncers based on their different goals:[39] Kutichaka – seeking atmospheric world; Bahudaka – seeking heavenly world; Hamsa – seeking penance world; Paramahamsa – seeking truth world; and Turiyatitas and Avadhutas seeking liberation in this life.

In some texts, such as Sannyasa Upanishad,[21] these were classified by the symbolic items the Sannyasins carried and their lifestyle. For example, Kutichaka sannyasis carried triple staffs, Hamsa sannyasis carried single staffs, while Paramahamsas went without them. This method of classification based on emblematic items became controversial, as anti-thematic to the idea of renunciation. Later texts, such as Naradaparivrajaka Upanishad stated that all renunciation is one, but people enter the state of Sannyasa for different reasons – for detachment and getting away from their routine meaningless world, to seek knowledge and meaning in life, to honor rites of Sannyasa they have undertaken, and because he already has liberating knowledge.[40]

- Other classifications

There were many groups of Hindu, Jain and Buddhist Sannyasis co-existing in pre-Maurya Empire era, each classified by their attributes, such as:[41] Achelakas (without clothes), Ajivika, Aviruddhaka, Devadhammika, Eka-satakas, Gotamaka, Jatilaka, Magandika, Mundasavaka, Nigrantha (Jains), Paribbajaka, Tedandikas, Titthiya and others.

Literature

The Dharmasūtras and Dharmaśāstras, composed about mid 1st millennium BC and later, place increasing emphasis on all four stages of Ashrama system including Sannyasa.[42] The Baudhayana Dharmasūtra, in verses 2.11.9 to 2.11.12, describes the four Ashramas as "a fourfold division of Dharma". The older Dharmasūtras, however, are significantly different in their treatment of Ashramas system from the more modern Dharmaśāstras, because they do not limit some of their Ashrama rituals to dvija men, that is, the three varnas – Brahmins, Kshatriyas and Vaishyas.[42] The newer Dharmaśāstra vary widely in their discussion of Ashrama system in the context of classes (castes),[43] with some mentioning it for three, while others such as Vaikhānasa Dharmasūtra including all four.[44]

The Dharmasūtras and Dharmaśāstras give a number of detailed but widely divergent guidelines on renunciation. In all cases, Sannyasa was never mandatory and was one of the choices before an individual. Only a small percentage chose this path. Olivelle[44] posits that the older Dharmasūtras present the Ashramas including Sannyasa as four alternative ways of life and options available, but not as sequential stage that any individual must follow.[42] Olivelle also states that Sannyasa along with the Ashrama system gained mainstream scholarly acceptance about 2nd century BC.[45]

Ancient and medieval era texts of Hinduism consider Grihastha (householder) stage as the most important of all stages in sociological context, as human beings in this stage not only pursue a virtuous life, they produce food and wealth that sustains people in other stages of life, as well as the offspring that continues mankind.[1][46] However, an individual had the choice to renounce any time he or she wanted, including straight after student life.[47]

When can a person renounce?

Baudhayana Dharmasūtra,[48] in verse II.10.17.2 states that anyone who has finished Brahmacharya (student) life stage may become ascetic immediately, in II.10.17.3 that any childless couple may enter Sannyasa anytime they wish, while verse II.10.17.4 states that a widower may choose Sannyasa if desired, but in general, states verse II.10.17.5, Sannyasa is suited after the completion of age 70 and after one's children have been firmly settled.[48] Other texts suggest the age of 75.[49]

The Vasiṣṭha and Āpastamba Dharmasūtras, and the later Manusmṛti describe the āśramas as sequential stages which would allow one to pass from Vedic studentship to householder to forest-dwelling hermit to renouncer.[50] However, these texts differ with each other. Yājñavalkya Smṛti, for example, differs from Manusmṛti and states in verse 3.56 that one may skip Vanaprastha (forest dwelling, retired) stage and go straight from the Grihastha (householder) stage to Sannyasa.

Who may renounce?

The question as to which vaṛṇa may, or may not, renounce is never explicitly stated in ancient or medieval dharma literature, the more modern Dharmaśāstras texts discuss much of renunciation stage in context of dvija men.[51] Nevertheless, Dharmaśāstra texts document people of all castes as well as women, entered Sannyasa in practice.[52]

What happened to renouncers' property and human rights?

After renouncing the world, the ascetic's financial obligations and property rights were dealt by the state, just like a dead person.[53] Viṣṇu Smriti in verse 6.27, for example, states that if a debtor takes Sannyasa, his sons or grandsons should settle his debts.[54] As to the little property a Sannyasin may collect or possess after renunciation, Book III Chapter XVI of Kautiliya's Arthashastra states that the property of hermits (vánaprastha), ascetics (yati, sannyasa), and student bachelors (Brahmachári) shall on their death be taken by their guru, disciples, their dharmabhratri (brother in the monastic order), or classmates in succession.[55]

Although a renouncer's practitioner's obligations and property rights were reassigned, he or she continued to enjoy basic human rights such as the protection from injury by others and the freedom to travel. Likewise, someone practicing Sannyasa was subject to the same laws as common citizens; stealing, harming, or killing a human being by a Sannyasi were all serious crimes in Kautiliya's Arthashastra.[56]

Renunciation in daily life

Later Indian literature debates whether the benefit of renunciation can be achieved (moksha, or liberation) without asceticism in the earlier stages of one's life. For example, Bhagavad Gita, Vidyaranya's Jivanmukti Viveka, and others believed that various alternate forms of yoga and the importance of yogic discipline could serve as paths to spirituality, and ultimately moksha.[57][58] Over time, four paths to liberating spirituality have emerged in Hinduism: Jñāna yoga, Bhakti yoga, Karma yoga and Rāja yoga.[59] Acting without greed or craving for results, in Karma yoga for example, is considered a form of detachment in daily life similar to Sannyasa. Sharma[60] states that, "the basic principle of Karma yoga is that it is not what one does, but how one does it that counts and if one has the know-how in this sense, one can become liberated by doing whatever it is one does", and "(one must do) whatever one does without attachment to the results, with efficiency and to the best of one's ability".[60]

Warrior ascetics

Ascetic life was historically a life of renunciation, non-violence and spiritual pursuit. However, in India, this has not always been the case. For example, after the Mongol and Persian Islamic invasions in the 12th century, and the establishment of Delhi Sultanate, the ensuing Hindu-Muslim conflicts provoked the creation of a military order of Hindu ascetics in India.[6][7] These warrior Ascetics, formed paramilitary groups called ‘‘Akharas’’ and they invented a range of martial arts.[6]

Nath Siddhas of the 12th century AD, may have been the earliest Hindu monks to resort to a military response after the Muslim conquest.[61] Ascetics, by tradition, led a nomadic and unattached lifestyle. As these ascetics dedicated themselves to rebellion, their groups sought stallions, developed techniques for spying and targeting, and they adopted strategies of war against Muslim nobles and the Sultanate state. Many of these groups were devotees of Hindu deity Mahadeva, and were called Mahants.[6] Other popular names for them was Sannyasis, Yogis, Nagas (followers of Shiva), Bairagis (followers of Vishnu) and Gosains from 1500 to 1800 AD; in some cases, these Hindu monks cooperated with Muslim fakirs who were Sufi and also persecuted.[7]

Warrior monks continued their rebellion through the Mughal Empire, and became a political force during the early years of British Raj. In some cases, these regiments of soldier monks shifted from guerrilla campaigns to war alliances, and these Hindu warrior monks played a key role in helping British establish themselves in India.[62] The significance of warrior ascetics rapidly declined with the consolidation of British Raj in late 19th century, and with the rise in non-violence movement by Mahatma Gandhi.[6]

Novetzke[63] states that some of these Hindu Warrior Ascetics were treated as folk heroes, aided by villagers and townspeople, because they targeted figures of political and economic power in a discriminatory state, and some of these warriors paralleled Robin Hood's lifestyle.[64]

Sannyasa Upanishads

Of the 108 Upanishads of the Muktika, the largest corpus is dedicated to Sannyasa and to Yoga, or about 20 each, with some overlap. The renunciation-related texts are called the Sannyasa Upanishads.[65] These are as follows:

| Veda | Sannyāsa |

|---|---|

| Ṛigveda | Nirvāṇa |

| Samaveda | Āruṇeya, Maitreya, Sannyāsa, Kuṇḍika |

| Krishna Yajurveda | Brahma, Avadhūta,[66] See Kathashruti |

| Shukla Yajurveda | Jābāla, Paramahaṃsa, Advayatāraka, Bhikṣuka, Turīyātīta, Yājñavalkya, Śāṭyāyani |

| Atharvaveda | Ashrama,[67] Nāradaparivrājaka (Parivrāt), Paramahaṃsa parivrājaka, Parabrahma |

Among the thirteen major or Principal Upanishads, all from the ancient era, many include sections related to Sannyasa.[68] For example, the motivations and state of a Sannyasi are mentioned in Maitrāyaṇi Upanishad, a classical major Upanishad that Robert Hume included among his list of "Thirteen Principal Upanishads" of Hinduism.[69] Maitrāyaṇi starts with the question, "given the nature of life, how is joy possible?" and "how can one achieve moksha (liberation)?"; in later sections it offers a debate on possible answers and its views on Sannyasa.[70]

In this body infected with passions, anger, greed, delusion, fright, despondency, grudge, separation from what is dear and desirable, attachment to what is not desirable, hunger, thirst, old age, death, illness, sorrow and the rest - how can one experience only joy? – Hymn I.3

The drying up of great oceans, the crumbling down of the mountains, the instability of the pole-star, the tearing of the wind-chords, the sinking down, the submergence of the earth, the tumbling down of the gods from their place - in a world in which such things occur, how can one experience only joy ?! – Hymn I.4

Dragged away and polluted by the river of the Gunas (personality), one becomes rootless, tottering, broken down, greedy, uncomposed and falling in the delusion of I-consciousness, he imagines: "I am this, this is mine" and binds himself, like a bird in the net. – Hymn VI.30

Just as the fire without fuel comes to rest in its place,

so also the passive mind comes to rest in its source;

When it (mind) is infatuated by the objects of sense, he falls away from truth and acts;

Mind alone is the Samsara, one should purify it with diligence;

You are what your mind is, a mystery, a perpetual one;

The mind which is serene, cancels all actions good and bad;

He, who, himself, serene, remains steadfast in himself - he attains imperishable happiness. – Hymn VI.34

Six of the Sannyasa Upanishads – Aruni, Kundika, Kathashruti, Paramahamsa, Jabala and Brahma – were composed before the 3rd-century CE, likely in the centuries before or after the start of the common era, states Sprockhoff; the Asrama Upanishad is dated to the 3rd-century, the Naradaparivrajaka and Satyayaniya Upanishads to around the 12th-century, and about ten of the remaining Sannyasa Upanishads are dated to have been composed in the 14th- to 15th-century CE well after the start of Islamic Sultanates period of South Asia in late 12th-century.[73][74]

The oldest Sannyasa Upanishads have a strong Advaita Vedanta outlook, and these pre-date Adi Shankara.[75] Most of the Sannyasa Upanishads present a Yoga and nondualism (Advaita) Vedanta philosophy.[76] This may be, states Patrick Olivelle, because major Hindu monasteries of early medieval period (1st millennium CE) belonged to the Advaita Vedanta tradition.[77] The 12th-century Shatyayaniya Upanishad is a significant exception, which presents qualified dualistic and Vaishnavism (Vishishtadvaita Vedanta) philosophy.[77][78]

See also

Notes

- An alternate term for either is sannyasin.[4]

References

- RK Sharma (1999), Indian Society, Institutions and Change, ISBN 978-8171566655, page 28

- S. Radhakrishnan (1922), The Hindu Dharma, International Journal of Ethics, 33(1): 1-22

- DP Bhawuk (2011), The Paths of Bondage and Liberation, in Spirituality and Indian Psychology, Springer, ISBN 978-1-4419-8109-7, pages 93-110

- Alessandro Monti (2002). Hindu Masculinities Across the Ages: Updating the Past. L'Harmattan Italia. pp. 41, 101–111. ISBN 978-88-88684-03-1.

- Harvey J. Sindima (2009), Introduction to Religious Studies, University Press of America, ISBN 978-0761847618, pages 93-94, 99-100

- David N. Lorenzen (1978), Warrior Ascetics in Indian History, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 98(1): 61-75

- William Pinch (2012), Warrior Ascetics and Indian Empires, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1107406377

- saMnyAsa Monier-Williams' Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Cologne Digital Sanskrit Lexicon, Germany

- Angus Stevenson and Maurice Wait (2011), Concise Oxford English Dictionary, ISBN 978-019-9601080, page 1275

- Patrick Olivelle (1981), Contributions to the Semantic History of Saṃnyāsa, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 101, No. 3, pages 265-274

- pravrajitA Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Koeln University, Germany

- yatin Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Koeln University, Germany

- Jamison and Witzel (1992), Vedic Hinduism, Harvard University Archives, page 47

- JF Sprockhoff (1981), Aranyaka und Vanaprastha in der vedischen Literatur, Neue Erwägungen zu einer alten Legende und ihren Problemen. Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde Südasiens und Archiv für Indische Philosophie Wien, 25, pages 19-90

- JF Sprockhoff (1976), Sanyāsa, Quellenstudien zur Askese im Hinduismus I: Untersuchungen über die Sannyåsa-Upaninshads, Wiesbaden, OCLC 644380709

- Patrick Olivelle (1976), Vasudevåśrama Yatidharmaprakåśa: a treatise on world renunciation, Brill Netherlands, OCLC 4113269

- GS Ghurye (1952), Ascetic Origins, Sociological Bulletin, Vol. 1, No. 2, pages 162-184;

For Sanskrit original: Rigveda Wikisource;

For English translation: Kesins Rig Veda, Hymn CXXXVI, Ralph Griffith (Translator) - Arthur Llewellyn Basham, The Origins and Development of Classical Hinduism, OCLC 19066012, ISBN 978-0807073001

- M Khandelwal (2003), Women in Ochre Robes: Gendering Hindu Renunciation, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791459225, pages 24-29

- In practice, women for example, entered Sannyasa in enough numbers that Chanakya's Arthashastra in 3rd century BC, mentions women ascetics (प्रव्रजिता, pravrajitā) in several chapters; see for example, R. Shamasastry (Translator) Chapter 23 page 160; also page 551

- A. A. Ramanathan, Sannyasa Upanishad The Theosophical Publishing House, Chennai, verses 2.23 - 2.29

- Mariasusai Dhavamony (2002), Hindu-Christian Dialogue: Theological Soundings and Perspectives, ISBN 978-9042015104, page 97

- SS Subramuniyaswami, The Two Paths of Dharma, p. 102, at Google Books, in What Is Hinduism? (Editors of Hinduism Today), Jan-Mar 2006, ISBN 978-1934145005, page 102

- Gavin Flood (2005), The Ascetic Self: Subjectivity, Memory and Tradition, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521604017, Chapter 4 with pages 105-107 in particular

- A Bhattacharya (2009), Applied Ethics, Center for Applied Ethics and Philosophy, Hokkaido University, ISBN 978-4990404611, pages 63-64

- Andrew Fort and Patricia Mumme (1996), Living Liberation in Hindu Thought, ISBN 978-0-7914-2706-4

- NE Thomas (1988), Liberation for Life: A Hindu Liberation Philosophy, Missiology: An International Review, 16(2): 149-162

- Knut Jacobsen (2011), in Jessica Frazier (Editor), The Bloomsbury companion to Hindu studies, Bloomsbury Academic, ISBN 978-1472511515, pages 74-83

- Klaus Klostermaier (1985), Mokṣa and Critical Theory, Philosophy East and West, 35(1): 61-71

- Andrew Fort (1998), Jivanmukti in Transformation, State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-7914-3904-6

- Lynn Denton (2004), Female Ascetics in Hinduism, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791461808, page 100

- M Khandelwal (2003), Women in Ochre Robes: Gendering Hindu Renunciation, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791459225, pages 34-40, 173

- P Van der Veer (1987), Taming the ascetic: Devotionalism in a Hindu monastic order, Man, 22(4): 680-695

- English Translation 1: Jeaneane D. Fowler (2012), The Bhagavad Gita: A Text and Commentary for Students, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1845193461, page 93;

English Translation 2: Edwin Arnold, Bhagavad Gita Chapter 5, Wikisource - Mariasusai Dhavamony (2002), Hindu-Christian Dialogue: Theological Soundings and Perspectives, ISBN 978-9042015104, page 96-97, 111-114

- Barbara Powell (2010), Windows Into the Infinite: A Guide to the Hindu Scriptures, Asian Humanities Press, ISBN 978-0875730714, pages 292-297

- KN Tiwari (2009), Comparative Religion, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120802933, pages 33-35

- Max Muller (Translator), Baudhayana Dharmasūtra Prasna II, Adhyaya 10, Kandika 18, The Sacred Books of the East, Vol. XIV, Oxford University Press, pages 279-281

- The Samnyasa Upanisads: Hindu Scriptures on Asceticism and Renunciation. pp. 98–99. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- The Samnyasa Upanisads: Hindu Scriptures on Asceticism and Renunciation. p. 99. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- MM Singh (1967), Life in North-Eastern India in Pre-Mauryan Times at Google Books, Motilal Banarsidass, pages 131-139

- Barbara Holdrege (2004), Dharma, in The Hindu World (Editors: Sushil Mittal and Gene Thursby), Routledge, ISBN 0 41521527-7, page 231

- (Olivelle 1993, pp. 25–34) translates them as classes, e.g. see footnote 70; while other authors translate them as castes

- Patrick Olivelle (1993), The Ashrama System: The History and Hermeneutics of a Religious Institution, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195344783

- Patrick Olivelle (1993), The Ashrama System: The History and Hermeneutics of a Religious Institution, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195344783, page 94

- Alban Widgery (1930), The Principles of Hindu Ethics, International Journal of Ethics, 40(2): 232-245

- What is Hinduism? (Editors of Hinduism Today), Two noble paths of Dharma, p. 101, at Google Books, Family Life and Monastic Life, Chapter 10 with page 101 in particular

- Max Muller (Translator), Baudhayana Dharmasūtra Prasna II, Adhyaya 10, Kandika 17, The Sacred Books of the East, Vol. XIV, Oxford University Press

- Dharm Bhawuk (2011), Spirituality and Indian Psychology: Lessons from the Bhagavad-Gita, Springer Science, ISBN 978-1441981097, page 66

- See (Olivelle 1993, pp. 84–106) discussion of the development of the āśrama system in "Renouncer and Renunciation in the Dharmaśāstras."

- See (Olivelle 1993, p. 111), "Renouncer and Renunciation in the Dharmaśāstras." p. 111

- For more references to renunciation by Śūdras and women, see (Olivelle 1993, pp. 111–115), "Renouncer and Renunciation in the Dharmaśāstras."

- See (Olivelle 1993, pp. 89–91), Saṃnyāsa Upaniṣads

- Law of Debt Vishnu Smriti, Julius Jolly (Translator), page 45

- Arthashastra - CHAPTER XVI: RESUMPTION OF GIFTS, SALE WITHOUT OWNERSHIP AND OWNERSHIP Book III, Wikisource

- See for example, Arthasastra - CHAPTER X: Fines in Lieu of Mutilation of Limbs Book IV, Wikisource; see also Book IV, Chapter XI which declared murder of an ascetic as a capital crime.

- Andrew O. Fort and Patricia Y. Mumme (1996), Living Liberation in Hindu Thought, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791427057, pages 8-12

- Gavin Flood (2005), The Ascetic Self: Subjectivity, Memory and Tradition, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521604017, pages 60-74

- Thor Johansen (2009), Religion and Spirituality in Psychotherapy: An Individual Psychology Perspective, Springer, ISBN 978-0826103857, pages 148-154

- A Sharma (2000), Classical Hindu Thought: An Introduction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195644418, pages 24-28

- Alf Hiltebeitel, Their name is Legion, in Rethinking India's Oral and Classical Epics, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0226340500, page 332-334 and footnote 104 on page 333

- P van der Veer (2007), Book Review, The American Historical Review, 112(1): 177-178,doi:10.1086/ahr.112.1.177

- "Christian Lee Novetzke", Wikipedia, 31 May 2019, retrieved 17 January 2020

- Christian Novetzke (2011), Religion and Public Memory: A Cultural History of Saint Namdev in India, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231141857, pages 173-175

- Patrick Olivelle (1998), Upaniṣhads. Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199540259

- Note: This exists in two manuscripts, Brihat and Laghu. Olivelle, Patrick (1992). The Samnyasa Upanisads. Oxford University Press. pp. x–xi. ISBN 978-0195070453.

- Paul Deussen (Translator), Sixty Upanisads of the Veda, Vol 2, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 568, 763-767

- Olivelle, Patrick (1992). The Samnyasa Upanisads. Oxford University Press. pp. x–xi, 4–9. ISBN 978-0195070453.

- Hume, Robert Ernest (1921), The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press

- Paul Deussen (Translator), Sixty Upanisads of the Veda, Vol 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 327-386

- Paul Deussen (Translator), Sixty Upanisads of the Veda, Vol 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 332-333

- Paul Deussen (Translator), Sixty Upanisads of the Veda, Vol 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 367, 373

- Olivelle, Patrick (1992). The Samnyasa Upanisads. Oxford University Press. pp. x–xi, 8–18. ISBN 978-0195070453.

- Sprockhoff, Joachim F (1976). Samnyasa: Quellenstudien zur Askese im Hinduismus (in German). Wiesbaden: Kommissionsverlag Franz Steiner. pp. 277–294, 319–377. ISBN 978-3515019057.

- Stephen H Phillips (1995), Classical Indian Metaphysics, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0812692983, page 332 with note 68

- Antonio Rigopoulos (1998), Dattatreya: The Immortal Guru, Yogin, and Avatara, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791436967, pages 62-63

- Olivelle, Patrick (1992). The Samnyasa Upanisads. Oxford University Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0195070453.

- Antonio Rigopoulos (1998), Dattatreya: The Immortal Guru, Yogin, and Avatara, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791436967, page 81 note 27

Cited books:

- Olivelle, Patrick (1993). The Ashrama System: The History and Hermeneutics of a Religious Institution. Oxford University Press. OCLC 466428084.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Articles on aspects of Sannyasa, Vairagya, and Brahmacharya

- 'The Song of the Sannyasin', poem by Swami Vivekananda

- Vows Of Sannyasa Saiva Siddhanta - Example covenant between a Hindu Sannyasin and a Hindu Monastic Order (PDF download)