Majdanek State Museum

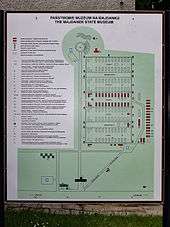

The Majdanek State Museum (Polish: Państwowe Muzeum na Majdanku)[3] is a memorial museum and education centre founded in the fall of 1944 on the grounds of the Nazi Germany Majdanek death camp located in Lublin, Poland. It was the first museum of its kind in the world,[4] devoted entirely to the memory of atrocities committed in the network of slave-labor camps and subcamps of KL Lublin during World War II. The museum performs several tasks including scholarly research into the Holocaust in Poland. It houses a permanent collection of rare artifacts, archival photographs, and testimony.[1]

Państwowe Muzeum na Majdanku | |

One of the exhibits at the Majdanek Museum | |

| |

| Established | 1944, confirmed by an act of the Polish parliament of July 2, 1947.[1] |

|---|---|

| Location | Majdanek, Poland |

| Coordinates | 51.1318°N 22.35579°E |

| Visitors | 121,404 (2011) [2] |

| Director | Tomasz Kranz |

| Website | http://www.majdanek.eu/ |

The museum

.jpg)

After the camp's liberation by the advancing Red Army on July 23, 1944, the site was formally protected.[7] It was preserved as a museum by the fall of 1944, when the War was still ongoing, the best example of Nazi Germany the Holocaust death camps, with largely intact gas chambers and crematoria. The camp became a state monument of martyrology by the 1947 decree of the Polish Parliament (Sejm).[1] In the same year, some 1,300 m³ of surface soil mixed with human ashes and fragments of bones were collected and arranged into a large mound (since turned into a mausoleum).[3] By comparison, the Auschwitz concentration camp liberated a half a year later, on January 27, 1945 was first declared a national monument in April 1946, but handed over to Poland by the Red Army only in 1947. The act of Polish Parliament of July 2, 1947 declared them both as state monuments of martyrology at the same time (Dz.U. 1947 nr 52 poz. 264/265).[8] Majdanek received the status of Poland's national museum in 1965.[3]

The retreating Germans did not have time to destroy the facility. During its 34 months of operation, more than 79,000 people were murdered at Majdanek main camp alone (59,000 of them Polish Jews) and between 95,000 and 130,000 people in the entire Majdanek system of subcamps.[9] Some 18,000 Jews were killed at Majdanek on November 3, 1943, during the largest single-day, single-camp massacre of the Holocaust,[10] named Harvest Festival (totalling 43,000 with 2 subcamps).[11]

In 1969, on the 25th anniversary of the Majdanek liberation, a stunningly emotional monument dedicated to Holocaust victims was erected on the grounds of the former Nazi extermination camp. It was designed by a Polish sculptor and architect Wiktor Tołkin,[3] who also designed the symbolic tombstone at Stutthof.[12] The monument consists of three parts, the symbolic Pylon (gate, 11 meters tall and 35 meters wide), the road, and the Mausoleum, containing a mound of ashes of the victims.[13] The Museum is also in possession of the archives left behind by the SS after a failed attempt at their destruction by Obersturmführer Anton Thernes, tried at the Majdanek Trials.[9]

Recent history

In 2003, a new obelisk was erected at Majdanek to the memory of Jewish victims of Erntefest. In 2004, a new branch of Majdanek State Museum was inaugurated at the Belzec extermination camp nearby. Belzec was created for implementing the Operation Reinhard during the Holocaust. And finally, in 2005 additional archeological works were conducted, resulting in new items being unearthed at the camp site, buried by Jewish prisoners in 1943.[3]

On September 2, 2009 the Majdanek Museum was awarded the Gold Medal Gloria Artis for outstanding contributions to Polish culture by Deputy State Secretary Minister Tomasz Merta. Two other recipients included the Muzeum Stutthof and the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.[14] There was a massive fire at one of the barracks in Majdanek on the night of August 9/10, 2010. Some 7,000 pairs of prisoners' shoes were destroyed – stated the museum administration. The cause of the blaze is unknown.[15] The museum states that bringing children under 13 to Majdanek is not advisable, because it is also forbidden to behave there noisily.[16] Since May 1, 2012 the Museum also serves as the main branch of the Sobibór Museum nearby.[17]

Notes and references

- "Regulamin organizacyjny Państwowego Muzeum na Majdanku". Dz. U. z 1947 r. nr 52, poz. 265. Biuletyn Informacji Publicznej (Bulletin of Public Information, Republic of Poland). 2006. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- "Statystyki". Frekwencja zwiedzających. Państwowe Muzeum na Majdanku. 2011. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- "Kalendarium". Powstanie Państwowego Muzeum (Creation of the Museum). Państwowe Muzeum na Majdanku. Archived from the original on 2011-02-13. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- "Majdanek State Museum". Lublin Sights. Lonely Planet. 2013. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

- "Crematorium at Majdanek". Jewish Virtual Library. 2013. Retrieved 2013-04-15.

- Danuta Olesiuk, Krzysztof Kokowicz. ""Jeśli ludzie zamilkną, głazy wołać będą." Pomnik ku czci ofiar Majdanka". Państwowe Muzeum na Majdanku (Majdanek State Museum). Archived from the original on 2014-10-23. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

- "Majdanek" (PDF). Majdanek concentration camp. Yad Vashem. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 27, 2007. Retrieved 2013-04-14.

- Dziennik Ustaw (2013). "Ustawa z dnia 2 lipca 1947 r." Internetowy System Aktow Prawnych. Kancelaria Sejmu RP. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- Paweł Reszka (Dec 23, 2005). "Majdanek Victims Enumerated. Changes in the history textbooks?". Gazeta Wyborcza. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. Archived from the original (Internet Archive) on November 6, 2011. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- USHMM (May 11, 2012). "Soviet forces liberate Majdanek". Lublin/Majdanek: Chronology. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C. Retrieved 2013-04-13.

- Jennifer Rosenberg. "Aktion Erntefest". 20th Century History. About.com Education. Archived from the original on December 27, 2016. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- PINNEX (2013). "Tołkin, Wiktor (b. 1922)". Encyklopedia Internautica. Interia.pl. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- Kazimierz S. Ożóg (June 7, 2006). "Pomnik Ofiar Majdanka (Majdanek Monument)". Pomniki Lublina (The Monuments of Lublin). Archived from the original (WebCite) on April 29, 2013. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- "Złote medale Zasłużony Kulturze Gloria Artis dla Muzeum Stutthof w Sztutowie, Państwowego Muzeum Auschwitz-Birkenau oraz Państwowego Muzeum na Majdanku". MKiDN.Gov.pl. 2 September 2009. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- GPL (10 August 2010). "Pożar na terenie byłego obozu na Majdanku. Straty na milion złotych" (in Polish). Gazeta.pl Lublin. Retrieved 2013-04-27.

- "Visiting the State Museum at Majdanek". General Rules and Regulations. The State Museum at Majdanek. 2006. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- MBOZS (2013). "Sobibór extermination camp. Commemoration". The State Museum at Majdanek. Archived from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- Państwowe Muzeum na Majdanku (The Majdanek State Museum) official website.

- Internet portal "KL Lublin" ((in Polish))

- Towarzystwo Opieki nad Majdankiem – Oddział w Białymstoku (The Society for the Preservation of Majdanek) official website.

![]()