Artur Axmann

Artur Axmann (18 February 1913 – 24 October 1996) was the German Nazi national leader (Reichsjugendführer) of the Hitler Youth (Hitlerjugend) from 1940 to the war's end in 1945. He was the last living Nazi with a rank equivalent to Reichsführer.

Artur Axmann | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reichsjugendführer | |

| In office 8 August 1940 – May 1945 | |

| Appointed by | Adolf Hitler |

| Preceded by | Baldur von Schirach |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 18 February 1913 Hagen, Province of Westphalia, Kingdom of Prussia, German Empire |

| Died | 24 October 1996 (aged 83) Berlin, Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Political party | Nazi Party (NSDAP) |

Early life

Axmann was born in Hagen, Westphalia, the son of an insurance clerk.[1] In 1916, his family moved to Berlin-Wedding, where his father died two years later. Young Axmann was a good student and received a scholarship to attend secondary school. He joined the Hitler Youth in November 1928, after he heard Nazi Gauleiter Joseph Goebbels speaking, and became leader of the local cell in the Wedding district.[2] He also joined the National Socialist Schoolchildren's League, where he distinguished himself as an orator.

Nazi career

In September 1931, Axmann joined the Nazi Party and the next year he was called to the NSDAP Reichsjugendführung[1] to carry out a reorganisation of Hitler Youth factory and vocational school cells. After the Nazi seizure of power in 1933, he rose to a regional leader and became Chief of the Social Office of the Reich Youth Leadership.[2]

Axmann directed the Hitler Youth in state vocational training and succeeded in raising the status of Hitler Youth agricultural work. In November 1934, he was appointed Hitler Youth leader of Berlin and from 1936 presided at the annual Reichsberufswettkampf competitions. On 30 January 1939 he was awarded the Golden Party Badge. Since October 1941, Axmann became a member of the Reichstag constituency of East Prussia.

After World War II began, Axmann was on active service on the Western Front until May 1940.[2] On 1 May 1940, he was appointed deputy to Nazi Reichsjugendführer Baldur von Schirach, whom he succeeded three months later on 8 August 1940.[2] As a member of the Wehrmacht 23rd Infantry Division, he was severely wounded on the Eastern Front in 1941, losing his right arm.[2]

In early 1943, Axmann proposed the formation of the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend to Heinrich Himmler, with servicemen drawn from the Hitler Youth.[3] Hitler approved the plan for the combat division to be made up of Hitler Youth members born in 1926. Thereafter, recruitment and training began.[3] In the last weeks of the war in Europe, Axmann commanded units of the Hitler Youth, which had been incorporated into the Home Guard (Volkssturm). His units consisted mostly of children and adolescents. They fought in the Battle of Seelow Heights and the Battle in Berlin.[2]

Berlin, 1945

During Hitler's last days in Berlin, Axmann was among those present in the Führerbunker.[1] During that time it was announced in the German Press that Axmann had been awarded the German Order, the highest decoration that the Nazi Party could bestow on an individual for his services to the Reich.[4] He and one other recipient, Konstantin Hierl, were the only holders of the award to survive the war and its consequences. All other recipients were either awarded it posthumously, or were killed during the war or its aftermath.[4]

On 30 April 1945, just a few hours before committing suicide, Hitler signed the order to allow a breakout. According to a report made to his Soviet captors by Obergruppenfuehrer Hans Rattenhuber, the head of Hitler's bodyguard, Axmann took the Walther PP pistol that had been removed from Hitler's sitting room in the Fuehrerbunker by Heinz Linge, Hitler's valet, which Hitler had used to commit suicide; saying that he would "hide it for better times".[5]

On 1 May, Axmann left the Führerbunker as part of a breakout group that included Martin Bormann, Werner Naumann and SS doctor Ludwig Stumpfegger.[6] Attempting to break out of the Soviet encirclement, their group managed to cross the River Spree at the Weidendammer Bridge.[7]

Leaving the rest of their group, Bormann, Stumpfegger, and Axmann walked along railway tracks to Lehrter railway station. Bormann and Stumpfegger followed the railway tracks towards Stettiner station. Axmann decided to go in the opposite direction of his two companions.[8] When he encountered a Red Army patrol, Axmann doubled back. He saw two bodies, which he later identified as Bormann and Stumpfegger, on the Invalidenstraße bridge near the railway switching yard (Lehrter Bahnhof), the moonlight clearly illuminating their faces.[8][9] He did not have time to check the bodies thoroughly, so he did not know how they died.[10] His statements were confirmed by the discovery of Bormann's and Stumpfegger's remains in 1972.[11]

Post-war

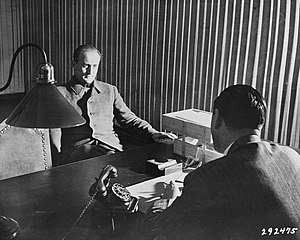

Axmann avoided capture by Soviet troops[12] and lived under the alias of "Erich Siewert" for several months. In December 1945, Axmann was arrested in Lübeck when a Nazi underground movement which he had been organising was uncovered by a U.S. Army counterintelligence operation.[12]

In May 1949, a Nuremberg denazification court sentenced Axmann to a prison sentence of three years and three months as a 'major offender'.[12] He was not found guilty of war crimes.[12] On 19 August 1958, a West Berlin court fined the former Hitler Youth leader 35,000 marks (approximately £3,000, or $8,300 USD) (equivalent to €74,527 in 2009), about half the value of his property in Berlin. The court found him guilty of indoctrinating German youth with National Socialism until the end of the war in Europe, but concluded he was not guilty of war crimes.[12]

Later life

After his release from custody, Axmann worked as a businessman with varying success. From 1971 he left Germany for a number of years, living on the Spanish island of Gran Canaria.[12] Axmann returned to Berlin in 1976, where he died on 24 October 1996, aged 83. His cause of death and details of his surviving family members were not disclosed.[13]

Portrayal in the media

Axmann was portrayed by Harry Brooks, Jr. in the 1973 British television production The Death of Adolf Hitler.[14]

References

Citations

- Joachimsthaler 1999, p. 283.

- Hamilton 1984, p. 247.

- McNab 2013, p. 295.

- Angolia 1989, pp. 223, 224.

- Vinogradov 2005, p. 195.

- Beevor 2002, pp. 382–383.

- Beevor 2002, p. 382.

- Le Tissier 2010, p. 188.

- Trevor-Roper 2002, p. 193.

- Beevor 2002, p. 383.

- Lang 1979, pp. 410, 432, 436.

- Hamilton 1984, p. 248.

- Cowell, Alan (7 November 1996). "Artur Axmann, 83, a Top Nazi Who Headed the Hitler Youth". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- "The Death of Adolf Hitler (1973) (TV)". IMDb.com. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

Bibliography

- Angolia, John (1989). For Führer and Fatherland: Political & Civil Awards of the Third Reich. R. James Bender Publishing. ISBN 978-0912138169.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beevor, Antony (2002). Berlin: The Downfall 1945. Viking-Penguin. ISBN 978-0-670-03041-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hamilton, Charles (1984). Leaders & Personalities of the Third Reich, Vol. 1. San Jose, CA: R. James Bender Publishing. ISBN 0-912138-27-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Joachimsthaler, Anton (1999) [1995]. The Last Days of Hitler: The Legends, The Evidence, The Truth. Brockhampton Press. ISBN 1-86019-902-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lang, Jochen von (1979). The Secretary. Martin Bormann: The Man Who Manipulated Hitler. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-50321-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Le Tissier, Tony (2010) [1999]. Race for the Reichstag: The 1945 Battle for Berlin. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-84884-230-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McNab, Chris (2013). Hitler's Elite: The SS 1939-45. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1782000884.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Trevor-Roper, Hugh (2002) [1947]. The Last Days of Hitler. London: Pan Books. ISBN 978-0-330-49060-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vinogradov, V. K. (2005). Hitler's Death: Russia's Last Great Secret from the Files of the KGB. Chaucer Press. ISBN 978-1-904449-13-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Axmann, Artur : "Das kann doch nicht das Ende sein." Hitlers letzter Reichsjugendführer erinnert sich. Koblenz: Bublies, 1995. ISBN 3-926584-33-5

- Selby, Scott Andrew (2012). The Axmann Conspiracy: The Nazi Plan for a Fourth Reich and How the U.S. Army Defeated It. Berkley (Penguin). ISBN 0425252701.