Robert Morrison (missionary)

Robert Morrison, FRS (5 January 1782 – 1 August 1834), was an Anglo[1]-Scottish[2] Protestant missionary to Portuguese Macao, Qing-era Guangdong, and Dutch Malacca, who was also a pioneering sinologist, lexicographer, and translator considered the "Father of Anglo-Chinese Literature".[3]

Robert Morrison | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait of Morrison by John Wildman | |||||||

| Born | 5 January 1782 | ||||||

| Died | 1 August 1834 (aged 52) | ||||||

| Occupation | Protestant missionary with the London Missionary Society | ||||||

| Spouse(s) | Mary Morrison (née Morton) Eliza Morrison (née Armstrong) | ||||||

| Parent(s) | James Morrison Hannah Nicholson | ||||||

| Religion | Presbyterian | ||||||

| Title | D.D. | ||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 馬禮遜 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 马礼逊 | ||||||

| |||||||

Morrison, a Presbyterian preacher, is most notable for his work in China. After twenty-five years of work he translated the whole Bible into the Chinese language and baptized ten Chinese believers, including Cai Gao, Liang Fa, and Wat Ngong. Morrison pioneered the translation of the Bible into Chinese and planned for the distribution of the Scriptures as broadly as possible, unlike the previous Roman Catholic translation work that had never been published.[4]

Morrison cooperated with such contemporary missionaries as Walter Henry Medhurst and William Milne (the printers), Samuel Dyer (Hudson Taylor's father-in-law), Karl Gützlaff (the Prussian linguist), and Peter Parker (China's first medical missionary). He served for 27 years in China with one furlough home to England. The only missionary efforts in China were restricted to Guangzhou (Canton) and Macau at this time. They concentrated on literature distribution among members of the merchant class, gained a few converts, and laid the foundations for more educational and medical work that would significantly impact the culture and history of the most populous nation on earth. However, when Morrison was asked shortly after his arrival in China if he expected to have any spiritual impact on the Chinese, he answered, "No sir, but I expect God will!"[5]

Life

Early life

Morrison was born on 5 January 1782 in Bullers Green, near Morpeth, Northumberland, England. He was the son of James Morrison, a Scottish farm laborer and Hannah Nicholson, an English woman, who were both active members of the Church of Scotland. They were married in 1768. Robert was the youngest son of eight children. At age three, Robert and his family moved to Newcastle where his father found more prosperous work in the shoe trade.

Robert's parents were devout Christians and raised their children to know the Bible and the Westminster Shorter Catechism according to Presbyterian ideals. At the age of 12 he recited the entire 119th Psalm (176 verses long) from memory in front of his pastor without a single mistake. John Wesley was still alive and many foreign mission agencies were being formed during this period of the Evangelical First Great Awakening.

In 1796, young Robert Morrison followed his uncle James Nicholson into apprenticeship and later joined the Presbyterian church in 1798.

By age 14 Robert left school and was apprenticed to his father's business.[6] For a couple of years he kept company in disregard of his Christian upbringing and fell occasionally into drunkenness. However, this behavior soon ended. In Robert's own words

It was about five years ago [1798] that I was much awakened to a sense of sin … and I was brought to a serious concern about my soul. I felt the dread of eternal condemnation. The fear of death compassed me about and I was led nightly to cry to God that he would pardon my sin, that he would grant me an interest in the Savior, and that he would renew me in the spirit of my mind. Sin became a burden. It was then that I experienced a change of life, and, I trust, a change of heart, too. I broke off from my former careless company, and gave myself to reading, meditation and prayer. It pleased God to reveal his Son in me, and at that time I experienced much of the "kindness of youth and the love of espousals." And though the first flash of affection wore off, I trust my love to and knowledge of the Savior have increased.

When Morrison was at work at his father's business he was employed at manual labour for twelve or fourteen hours a day; yet he seldom omitted to find time for one or two hours of reading and meditation. He read and re-read frequently those few books he was able to obtain. The diary, which he began to keep very early in his life, shows that he did much self-introspection; his earnestness was clearly intense, and his sense of his own shortcomings continued to be remarkably vivid.

Soon he wanted to become a missionary and in 1801, he started learning Latin, Greek Hebrew[6] as well as systematic theology and shorthand from the Rev. W. Laidler, a Presbyterian minister in Newcastle, but his parents were opposed to his new vocation. During this period, Robert often spent free time in the garden in quiet meditation and prayer. At work, the Bible or some other book such as Matthew Henry's Commentary was open before him while his hands were busy. He regularly attended church on Sundays, visited the sick with the "Friendless Poor and Sick Society", and in his spare time during the week instructed poor children. He shared his faith in Christ with another young apprentice and to a sailor, showing a deep concern for the conversion of friends and family.

On 7 January 1803 he entered the Hoxton Academy in London and was trained as Congregationalist minister.[6] He visited the poor and sick and preached in the villages around London.

By the age of 17 Morrison had been moved reading about the new missionary movement in The Evangelical Magazine and The Missionary Magazine. However, he had promised his mother he would not go abroad so long as she lived and was present to care for her during her last illness, when he received her blessing to proceed.

Preparing to be a missionary

After his mother's death in 1804, he joined the London Missionary Society. He had applied to the Society in a letter dated 27 May 1804, offering himself for missionary service. The next day he was interviewed by the board and accepted at once without a second interview. The next year, he went to David Bogue's Academy in Gosport (near Portsmouth) for further training. For a while he was torn between Timbuktu in Africa and China as possible fields of service. His prayer was:

that God would station him in that part of the missionary field where the difficulties were greatest, and, to all human appearances, the most insurmountable.

In 1798, just when the young Robert had been converted, the Rev. William Willis Moseley of Northamptonshire issued a letter urging "the establishment of a society for translating the Holy Scriptures into the languages of the populous oriental nations." He came across a manuscript of most of the New Testament translated into Chinese (probably by earlier Jesuit missionaries) in the British Museum. He immediately printed 100 copies of a further tract "on the importance of translating and publishing the Holy Scriptures into the Chinese language." Copies were sent to all the Church of England bishops and the new mission agencies. Most gave discouraging replies, giving such reasons as the cost and "utter impossibility" of spreading the books inside China. But a copy reached Dr. Bogue, the head of the Hoxton Academy. He replied that if he had been younger he would have "devoted the rest of his days to the propagation of the gospel in China". Dr. Bogue promised to look out for suitable missionary candidates for China. He chose Morrison who soon after turned his attention away from Africa and focused entirely on China. Robert wrote to a friend urging him to become his colleague in his new work,

I wish I could persuade you to accompany me. Take into account the 350 million souls in China who have not the means of knowing Jesus Christ as Savior…

He returned to London and studied medicine with Dr. Blair at St. Bartholomew's Hospital, and astronomy with Dr. Hutton at the Greenwich Observatory. After the decision of the Directors as to his destination, Morrison had most diligently and laboriously pursued the study of Chinese. He learned the Chinese language from a student that he shared lodgings with, called Yong Sam-tak from Canton City. At first they did not get on well together. Morrison absent-mindedly burned a piece of paper with some Chinese characters on it – and infuriated the superstitions of his Chinese mentor, who left for three days. From that time on, Morrison wrote his characters on a piece of tin that could be erased. They continued to work together and studied an early Chinese translation of Gospels named Evangelia Quatuor Sinice which was probably written by a Jesuit, as well as a hand-written Latin-Chinese dictionary. Yong Sam-tak eventually joined him in family worship. In this way Morrison made considerable progress in speaking and writing one of the most difficult of languages for an English-speaking person to learn. The hope of the Directors was that, first of all, Morrison would master the ordinary speech of the people, and so be able to compile a dictionary, and perhaps make a translation of the Scriptures for the benefit of all future missionaries. To accomplish this, it was first of all necessary to get a footing on Chinese soil, and not hopelessly offend the Chinese authorities. At this time, dealings of foreigners with the people, except for purposes of trade, was absolutely forbidden. Every foreigner was strictly interrogated on landing as to what his business might be; the price for giving the wrong answers might be unceremonious return on the next vessel. Morrison was aware of the dangers.[7] He traveled to visit his family and bid them farewell in July 1806, preaching 13 times in London, Edinburgh and Glasgow.

Early missionary work

Morrison was ordained in London on 8 January 1807 at the Scotch church and was eager to go to China. On 31 January, he sailed first to America. The fact that the policy of the East India Company was not to carry missionaries, and that there were no other ships available that were bound for China, forced him to stop first in New York City. Morrison spent nearly a month in the United States . He was very anxious to secure the good offices of the American Consul at Guangzhou, as it was well known that he would need the influence of someone in authority, if he was to be permitted to stay in China. The promise of protection was made from the United States consul, and on 12 May, he boarded a second vessel, the Trident, bound for Macau.[8]

The Trident arrived in Macau on 4 September 1807 after 113 days at sea. The first move of the newcomer was to present his letters of introduction to some leading Englishmen and Americans, in Macau and Guangzhou. He was kindly received, but he needed a bold heart to bear up, without discouragement, under their frank announcement of the apparently hopeless obstacles in the way of the accomplishment of his mission. George Thomas Staunton discouraged him from the idea of being a missionary in China. First of all, Chinamen were forbidden by the Government to teach the language to anyone, under penalty of death. Secondly, no one could remain in China except for purposes of trade. Thirdly, the Roman Catholic missionaries at Macau, who were protected by the Portuguese, would be bitterly hostile, and stir up the people against a Protestant missionary. On 7 September, he was expelled by the Roman Catholic authorities in Macau and went to the Thirteen Factories outside Canton City. The chief of the American factory at Canton offered the missionary for the present a room in his house; and there he was most thankful to establish himself, and think over the situation. Shortly afterwards he made an arrangement for three months, with another American gentleman, to live at his factory. He effectively passed himself off as an American. The Chinese, he found, did not dislike and suspect Americans as much as they did the English. Still Morrison's presence did excite suspicions, and he could not leave his Chinese books about, lest it should be supposed that his object was to master the language. Certain Roman Catholic natives such as Abel Yun were found willing to impart to him as much of the Mandarin Chinese as they could but he soon found that the knowledge of this did not enable him to understand, or make himself understood by, the common people; and he had not come to China simply to translate the Scriptures into the speech of a comparatively small aristocratic class.[8]

During these early months his trials and discouragements were great. He had to live in almost complete seclusion. He was afraid of being seen abroad. His Chinese servants cheated him. The man who undertook to teach him demanded extortionate sums. Another bought him a few Chinese books, and robbed him handsomely in the transaction. Morrison was alarmed at his expenditure. He tried living in one room, until he had severe warnings that fever would be the outcome. His utter loneliness oppressed him. The prospect seemed cheerless in the extreme.

At first Morrison conformed as exactly as he could to Chinese manners. He tried to live on Chinese food, and became an adept with the chopsticks. He allowed his nails to grow long, and cultivated a queue. Milne noted that "[h]e walked about the Hong with a Chinese frock on, and with thick Chinese shoes".[9] In time he came to think this was a mistaken policy. So far as the food was concerned, he could not live on it in health; and as for the dress, it only served to render him the more unusual, and to attract attention where he was anxious to avoid publicity. A foreigner dressed up in Chinese clothes excited suspicions, as one who was endeavoring by stealth to insinuate himself into Chinese society, so as to introduce his contraband religion surreptitiously. Under these circumstances Morrison resumed the European manners of the Americans and English.

Morrison's position was menaced by political troubles. One move in the war with France, which England was waging at this time, was that an English squadron bore down on Macau, to prevent the French from striking a blow at English trade. This action was resented by the Chinese authorities at Guangzhou, and reprisals were threatened on the English residents there. Panic prevailed. The English families had to take refuge on ships, and make their way to Macau. Among them came Morrison, with his precious luggage of manuscripts and books. The political difficulty soon passed, and the squadron left; but the Chinese were even more intensely suspicious of the "foreigner" than before.

East India Company

Morrison fell ill and returned to Macau on 1 June 1808. Fortunately he had mastered Mandarin and Cantonese during this period. Morrison was miserably housed at Macau. It was with difficulty he induced anyone to take him in. He paid an exorbitant price for a miserable top-floor room, and had not been long in it before the roof fell in with a crash. Even then he would have stayed on, when some sort of covering had been patched up, but his landlord raised his rent by one-third, and he was forced to go out again into the streets. Still he struggled on, laboring at his Chinese dictionary, and even in his private prayers pouring out his soul to God in broken Chinese, that he might master the native tongue. So much of a recluse had he become, through fear of being ordered away by the authorities, that his health greatly suffered, and he could only walk across his narrow room with difficulty. But he toiled on.

Morrison strove to establish relations between himself and the people. He attempted to teach three Chinese boys who lived on the streets in an attempt to help both them and his own language skills. However, they treated him maliciously and he was forced to let them go.

In 1809, he met 17-year-old Mary Morton and married her on 20 February that year in Macau.[10] They had three children: James Morrison (b. 5 March 1811, died on the same day), Mary Rebecca Morrison (b. July 1812), and John Robert Morrison (b. 17 April 1814). Mary Morrison died of cholera on 10 June 1821 and is buried in the Old Protestant Cemetery in Macau.[10]

On the day of their marriage Robert Morrison was appointed translator to the East India Company with a salary of £500 a year. He returned to Guangzhou alone since foreign women were not allowed to reside there.

This post afforded him, what most he needed, some real security that he would be allowed to continue at his work. He had now a definite commercial appointment, and it was one which in no way hindered the prosecution of the mission, which always stood first in his thoughts. The daily work of translation for the company assisted him in gaining familiarity with the language, and increased his opportunities for intercourse with the Chinese. He could now go about more freely and fearlessly. Already his mastery of the Chinese tongue was admitted by those shrewd businessmen, who perceived its value for their own commercial negotiations.

The sea between Macau and Canton was full of pirates, and the Morrisons had to make many anxious voyages. Sometimes the cry of alarm would be raised even in Guangzhou, as the pirate raids came within a few miles of the city; and the authorities were largely helpless. The perils of their position, as well as its solitude, seem to have greatly and painfully affected Mary. She was affected by unhealthy anxiety. There was no society at Guangzhou that was congenial to them. The English and American residents were kind, but had little sympathy with their work, or belief in it. The Chinese demurred about burial of their first child. Very sorrowfully Morrison had to superintend his interment on a mountainside. At that time his wife was dangerously ill. All his comrades at the company's office thought him a fool. His Chinese so-called assistants robbed him. Letters from England came but seldom.

The Chinese grammar was finished in 1812, and sent to Bengal for printing, and heard no more of for three anxious, weary years for Morrison. But it was highly approved and well printed, and it was a pivotal piece of work done towards enabling England and America to understand China. Morrison went on to print a tract and a catechism. He translated the book of Acts into Chinese, and was overcharged to the extent of thirty pounds for the printing of a thousand copies. Then Morrison translated the Gospel of Luke, and printed it. The Roman Catholic bishop at Macau, on obtaining a copy of this latter production, ordered it to be burned as a heretical book. So to the common people it must have appeared that one set of Christians existed to destroy what the other set produced. The facts did not look favorable for the prosperity of Christianity in China.

The machinery of the Chinese criminal tribunal was set in motion when the Chinese authorities read some of his printed works. Morrison was first made aware of the coming storm by the publication of an edict, directed against him and all Europeans who sought to undermine Chinese religion. Under this edict, to print and publish Christian books in Chinese was declared a capital crime. The author of any such work was warned that he would subject himself to the penalty of death. All his assistants would render themselves liable to various severe forms of punishment. The mandarins and all magistrates were enjoined to act with energy in bringing to judgment any who might be guilty of contravening this edict. Morrison forwarded a translation of this famous proclamation to England, at the same time announcing to the Directors that he purposed to go quietly and resolutely forward. For himself, indeed, he does not seem to have been afraid. Undoubtedly his position under the East India Company was a great protection to him; and a grammar and dictionary were not distinctively Christian publications. But the Directors were even then sending out to join him the Rev. William Milne and his wife, and Morrison knew that this edict would make any attempt of another missionary to settle at Guangzhou exceedingly hazardous and difficult.

On 4 July 1813, at about three o'clock in the afternoon, it being the first Sunday in the month, Mr. and Mrs. Morrison were sitting down together to the "Lord's Supper" at Macau. Just as they were about to begin their simple service, a note was brought to them to say that Mr. and Mrs. William Milne had landed. Morrison used all his influence with those in whose hands the decision lay as to whether Milne should be allowed to remain. Five days after the newcomers had arrived, a sergeant was sent from the Governor to Morrison's house, who summoned him. The decision was short and stern: Milne must leave in eight days. Not only had the Chinese vehemently opposed his settlement, but the Roman Catholics were behind them in urging that he be sent away. From the English residents at Macau, Morrison received no assistance either for they feared lest, if any complications arose through Morrison, their commercial interests might be prejudiced. For the present Mr. and Mrs. Milne went on to Guangzhou, where the Morrisons followed them and soon both families were established in that city, waiting the next move of the authorities. Morrison spent this time assisting Milne to learn to speak Chinese.

In 1820, Morrison met the American businessman David Olyphant in Canton, which marked the start of a long friendship between the two men and resulted in Olyphant naming his son Robert Morrison Olyphant.[11]

Return to England

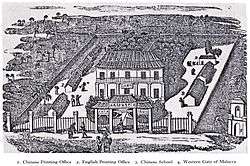

In 1822 Morrison visited Malacca and Singapore, returning to England in 1824.

The University of Glasgow had made him a Doctor of Divinity in 1817. Upon his return to England, Morrison was made a Fellow of the Royal Society. He brought a large library of Chinese books to England, which were donated to the London University College. Morrison began The Language Institution in Bartlett's Buildings in Holborn, London during his stay there, to teach missionaries.

The years 1824 and 1825 were spent by Morrison in England, where he presented his Chinese Bible to King George IV, and was received by all classes with great demonstrations of respect. He busied himself in teaching Chinese to classes of English gentlemen and English ladies, and in stirring up interest and sympathy on behalf of China. Before returning to his missionary labours he was married again, in November 1824 to Eliza Armstrong, with whom he had five more children. The new Mrs. Morrison and the children of his first marriage returned with him to China in 1826.

An incident of the voyage will illustrate the perils of those days, as well as Morrison's fortitude. After a terrible spell of storm, the passengers were alarmed to hear the clanking of swords and the explosion of firearms. They soon learned that a mutiny had broken out among the seamen, who were wretchedly paid, and who had taken possession of the forepart of the vessel, with the intention of turning the cannon there against the officers of the ship. It was a critical moment. At the height of the alarm, Morrison calmly walked forward among the mutineers, and, after some earnest words of persuasion, induced the majority of them to return to their places; the remainder were easily captured, flogged, and put in irons.

At Singapore, Morrison was confronted with fresh trials. The Singapore Institution, now Raffles Institution, which has one House named after him, had been in process of formation there, on his departure for England, similar to the college at Malacca. Little progress had been made with it. A new governor manifested less interest, and Morrison had not been present to see that the work went on. After a stay here for purposes of organization, the missionary and his family went on to Macau, and subsequently Morrison proceeded to Guangzhou, where he found that his property had been also neglected in his absence.

Final days in China

Together the Morrisons returned to China in 1826.

Changes in the East India Company had brought him into contact with new officials, some of whom had not the slightest respect for the calling of the missionary, and were inclined to assume a high hand, until Morrison's threat to resign induced a more respectful temper. The relations, too, between the English traders and the Chinese officials were daily becoming more strained. Morrison strongly disapproved of much of the correspondence which it fell to his lot to conduct with the native mandarins. Clouds were gathering, which were to break in a few years' time. There were grave faults on both sides. The officiousness and tyranny of the mandarins were hard to bear, but on the English rested the more grievous responsibility of resolving to force a trade in opium on the Chinese people. War would come later, and might would be on the side of England, and right on the side of China. The whole future of missions would be prejudiced by this awful mistake. The ports would be opened to opium first, to Christianity second.

On Morrison's visit to England, he had been able to leave a Chinese native teacher, Liang Fa, one of Milne's converts, to carry on what work he could among the people. This man had already endured much for his faith, and he proved entirely consistent and earnest during the long period of Morrison's absence. Other native Christians were baptized; and the little Church grew, while at the same time it was well known that many believed in secret, who did not dare to challenge persecution and ostracism by public confession. American missionaries were sent to help Morrison, and more Christian publications were issued. Morrison welcomed the arrival of the Americans, because they could conduct the service for English residents, and set him free to preach and talk to the Chinese who could be gathered together to listen to the Gospel. In 1832 Morrison could write:

There is now in Canton a state of society, in respect of Chinese, totally different from what I found in 1807. Chinese scholars, missionary students, English presses and Chinese Scriptures, with public worship of God, have all grown up since that period. I have served my generation, and must the Lord know when I fall asleep.

The Roman Catholic bishop rose against Morrison in 1833, leading to the suppression of his presses in Macau and removing his preferred method of spreading knowledge of Christ. His native agents, however, continued to circulate publications that had already been printed.[12] During this period Morrison also contributed to Karl Gützlaff's Eastern Western Monthly Magazine,[13] a publication aimed at improving Sino-Western understanding.

In 1834 the monopoly of the East India Company on trade with China ended. Morrison's position with the company was abolished and his means of sustenance ceased. He was subsequently appointed Government translator under Lord Napier, but only held the position for a few days.

Morrison prepared his last sermon in June 1834 on the text, "In my Father's house are many mansions." He was entering his last illness, and his solitude was great, for his wife and family had been ordered to England. On 1 August the pioneer Protestant missionary to China died. He died at his residence: Number six at the Danish Hong in Canton (Guangzhou) at the age of 52 in his son's arms. The following day, his remains were removed to Macau, and buried in the Old Protestant Cemetery on 5 August next to his first wife and child. He left a family of six surviving children, two by his first wife, and four by his second. His only daughter was married to Benjamin Hobson, a medical missionary in 1847.

Epitaph

Morrison was buried in the Old Protestant Cemetery in Macau. The inscription on his marker reads:

Sacred to the memory of Robert Morrison DD.,

The first protestant missionary to China,

Where after a service of twenty-seven years,

cheerfully spent in extending the kingdom of the blessed Redeemer

during which period he compiled and published

a dictionary of the Chinese language,

founded the Anglo Chinese College at Malacca

and for several years laboured alone on a Chinese version of

The Holy Scriptures,

which he was spared to see complete and widely circulated

among those for whom it was destined,

he sweetly slept in Jesus.

He was born at Morpeth in Northumberland

5 January 1782

Was sent to China by the London Missionary Society in 1807

Was for twenty five years Chinese translator in the employ of

The East India Company

and died in Canton 1 August 1834.

Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord from henceforth

Yea saith the Spirit

that they may rest from their labours,

and their works do follow them.

Legacy and honours

Morrison had amassed "the most comprehensive library of Chinese literature in Europe" which formed the core of his The Language Institution in Bartlett's Building, London. His widow put all 900 books up for sale in 1837 for £2,000.[14]

The Morrison Hill district of Hong Kong and its adjoining road, Morrison Hill Road, are named for Morrison as was the Morrison School erected upon it by the Morrison Education Society and completed shortly before Morrison's death in 1843.[15][16] The Morrison Hill Swimming Pool at the centre of the former hill is a present public swimming pool in Hong Kong.[17]

The University of Hong Kong's Morrison Hall, first established in 1913 as a "Christian hostel for Chinese students", was named for Morrison by its patrons, the London Missionary Society.[18]

Morrison House in YMCA of Hong Kong Christian College, which was founded by YMCA of Hong Kong, was named in commemoration of Morrison.[19]

Morrison Building is a declared monument of Hong Kong. It was the oldest building in the Hoh Fuk Tong Centre located at Castle Peak Road, San Hui, Tuen Mun, the New Territories.[20]

Morrison Academy is an international Christian school founded in Taichung, Taiwan.[21]

Work

Missionary work

Morrison produced a Chinese translation of the Bible. He also compiled a Chinese dictionary for the use of Westerners. The Bible translation took twelve years and the compilation of the dictionary, sixteen years. During this period, in 1815, he left the employment of the East India Company.[22]

By the end of the year 1813, the whole of the New Testament translation was completed and printed. The translator never claimed that it was perfect. On the contrary, he readily conceded its defects. But he claimed for it that it was a translation of the New Testament into no stilted, scholastic dialect, but into the genuine colloquial speech of the Chinese. The possession of a large number of printed copies led the two missionaries to devise a scheme for their wide and effective distribution.

At this time several parts of the Malay Peninsula were under English protection. English Governors were resident, and consequently it seemed a promising field for the establishment of a mission station. The station would be within reach of the Chinese coast, and Chinese missionaries might be trained there whose entrance into China would not excite the same suspicions that attached to the movements of English people. The two places specially thought of were the island of Java, and Malacca on the Malay Peninsula.

It was well known that many thousands of Chinese were scattered through these parts, and Milne traveled around surveying the country, and distributing tracts and Testaments as opportunity offered. The object of the two missionaries was now to select some quiet spot where, under protection, the printing press might be established, and Chinese missionaries trained. Malacca had this advantage, that it lay between India and China, and commanded means of transport to almost any part of China and the adjoining archipelago. After much deliberation it was determined to advise the directors that Milne should proceed to establish himself at Malacca.

In this year Morrison baptized the first convert on 14 May 1814 (seven years after his arrival). The first Protestant Chinese Christian was probably named Cai Gao. (His name was variously recorded by Morrison as Tsae A-fo, A-no, and A-ko.) Morrison acknowledged the imperfection of this man's knowledge and did not mention his own role in Cai's baptism until much later, but he claimed to rely on the words "If thou believest with all thy heart!" and administered the rite. From his diary the following was noted:

At a spring of water, issuing from the foot of a lofty hill, by the sea-side, away from human observation, I baptised him in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit... May he be the first fruits of a great harvest.

About the same time the East India Company undertook the cost of printing Morrison's Chinese Dictionary. They spent £10,000 on the work, bringing out for the purpose their own printer, Peter Perring Thoms, along with a printing press. The Bible Society voted two grants of £500 each towards the cost of printing the New Testament. One of the Directors of the East India Company also bequeathed to Morrison $1000 for the propagation of the Christian religion. This he devoted to the cost of printing a pocket edition of the New Testament. The former edition had been inconveniently large; and especially in the case of a book that was likely to be seized and destroyed by hostile authorities, this was a serious matter. A pocket Testament could be carried about without difficulty. The small edition was printed, and many Chinese departed from Guangzhou into the interior with one or more copies of this invaluable little book secreted in his dress or among his belongings.[22]

Mary Morrison was ordered to England, and she sailed with her two children, and for six years her husband was to toil on in solitude.

In 1817 Morrison accompanied Lord Amherst's embassy to Beijing. His own knowledge of China was very considerably enlarged by this. He was sent by the company on an embassy to the Emperor at Beijing in the capacity of interpreter. The journey took him through many cities and country districts, and introduced him to some novel aspects of Chinese life and character. The object of the embassy was not attained, but to Morrison the experience was invaluable; and it served, not only to revive his health, but to stimulate his missionary zeal. Through all that vast tract of country, and among that innumerable population, there was not one solitary Protestant missionary station.

Another accomplishment of Morrison's, in which he proved himself a pioneer, was his establishment of a public dispensary at Macau in 1820, where native diseases might be treated more humanely and effectively than was customary in China. Morrison was profoundly stirred by the misery, the poverty, and the unnecessary suffering of the Chinese poor. The people were constantly persuaded to expend their all on Traditional Chinese medicine he considered useless. Morrison sought out an intelligent and skilful Chinese practitioner, and placed him at the head of his dispensary. This man, who had learned the main principles of European treatment, received great help from Dr. Livingstone, a friend of Morrison's, who was much interested in this attempt to alleviate the sufferings of the poorer Chinese.

Morrison and Milne also established a school for Chinese and Malay children in 1818. The school, named Anglo-Chinese College (later called Ying Wa College), was moved to Hong Kong around 1843 after the territory became a British possession. The institution exists today in Hong Kong as a secondary school for boys. Milne received the support of the English Governor at Malacca. He represented the extreme eastern outpost of Protestant missions in Asia, and Morrison assumed the name "Ultra-Ganges" mission.

Morrison and Milne translated the Old Testament together; and although Morrison had the advantage of a far more intimate knowledge of the language, and was thus able to revise the work of his colleague, Milne also had made remarkable progress in his mastery of Chinese. The press was kept steadily at work. Tracts of various kinds were issued. Morrison wrote a little book called "A Tour round the World," the object of which was to acquaint his Chinese readers with the customs and ideas of European nations, and the benefits that had flowed from Christianity.

As if his manifold activities in China were not sufficient to occupy him, Morrison began to formulate an even broader scheme for the evangelization of China. This was, to build at Malacca what he called an "Anglo-Chinese College". Its object was to introduce the East to the West, and the West to the East; in other words, to mediate between the two civilizations, and thus to prepare the way for the quiet and peaceful dissemination of Christian thought in China.[23]

The proposal was warmly taken up. The London Missionary Society gave the ground. The Governor of Malacca and many residents subscribed. Morrison himself gave £1000 out of his small property to establish the college. The building was erected and opened. Printing presses were set up, and students were enrolled. Milne was the president; and while no student was compelled to declare himself a Christian, or to attend Christian worship, it was hoped that the strong Christian influence would lead many of the purely literary students to become teachers of Christianity. Intense as were his Christian convictions, he could sanction nothing that would do deliberate violence to the convictions of another; and he had a faith that Christian truth would eventually prevail on its own merits, and need never fear to be set side by side with the truths that other religious systems contain. Eight or nine years after its foundation, Mr. Charles Majoribanks, M.P. for Perth, in a Government report on the condition of Malacca, singled out this institution for very high praise on account of its thoroughly sound, quiet, and efficient work.

A settlement having now been established, under British protection, and in the midst of those islands which are inhabited by a large Malay and Chinese population, reinforcements were sent out from England. After a period in Malacca they were sent on from there to various centers: Penang, Java, Singapore, Amboyna, wherever they could find a footing and establish relations with the people. In this way many new stations sprang up in the Ultra-Ganges Mission. A magazine was issued, entitled The Gleaner, the object of which was to keep the various stations in touch with one another, and disseminate information as to progress in the different parts. The various printing presses poured forth pamphlets, tracts, catechisms, translations of Gospels, in Malay or in Chinese. Schools were founded for the teaching of the children: for the great obstacle to the free use of the printing press was that so few of the people comparatively could read. The missionaries had to be many-sided, now preaching to the Malays, now to the Chinese, now to the English population; now setting up types, now teaching in the schools; now evangelizing new districts and neighbouring islands, now gathering together their little congregations at their own settlement. The reports do not greatly vary from year to year. The work was hard, and seemingly unproductive. The people listened, but often did not respond. The converts were few.

Mary Morrison returned to China only to die in 1821; Mrs. Milne had died already. Morrison was 39. In 1822 William Milne died, after a brief but valuable missionary life, and Morrison was left to reflect that he alone of the first four Protestant missionaries to China was now left alive. He reviewed the history of the mission by writing a retrospect of these fifteen years. China was still as impervious as ever to European and Christian influence; but the amount of solid literary work accomplished was immense.[22]

Scholarly work

_Chinese-English_Dictionary_(Radical)_-_p.442.jpg)

Robert Morrison's Dictionary of the Chinese Language was the first Chinese–English, English–Chinese dictionary,[24] largely based on the Kangxi Dictionary and a Chinese rhyming dictionary of the same era. This meant that his tonal markings were those of Middle Chinese rather than those actually spoken in his age. Owing to the tutors available to him, his transcriptions were based on Nanjing Mandarin rather than the Beijing dialect.[n 1][26]

Works

This is a list of scholarly, missionary and other works by Robert Morrison :

- Robert Morrison (1812). Horae Sinicae: Translations from the Popular Literature of the Chinese. London.

- Robert Morrison (1813). Hsin i Chao Shu. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- Robert Morrison (1815). A Grammar of the Chinese Language. Serampore: Printed at the Mission-Press. pp. 280. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- Authors Antonio Montucci; Horae Sinicae; Robert Morrison (1817). Urh-chĭh-tsze-tëen-se-yĭn-pe-keáou; being a parallel drawn between the two intended Chinese dictionaries, by R. Morrison and A. Montucci. Together with Morrison's Horæ Sinicæ [&c.]. Macao, China: T. Cadell and W Davies. p. 141. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- Robert Morrison (1817). A view of China for philological purposes, containing a sketch of Chinese chronology, geography, government, religion & customs. Macao, China: Printed at the Honorable the East India Company's Press by P.P. Thoms ; published and sold by Black, Parbury, and Allen, Booksellers to the Honorable East India Company, London. Retrieved 15 May 2011. Alt URL

- Morrison, Robert (1815–1823). A Dictionary of the Chinese Language, in Three Parts. Macao, China: Printed at the Honorable the East India Company's Press by P.P. Thoms. in six volumes:

- Part I, Vol. I - Robert Morrison (1815). A Dictionary of the Chinese Language, in Three Parts: Chinese and English, arranged according to the radicals. Macao, China: Printed at the Honorable the East India Company's Press by P.P. Thoms. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- Part I, Vol. II - Robert Morrison (1822). A Dictionary of the Chinese Language, in Three Parts: Chinese and English, arranged according to the radicals. Macao, China: Printed at the Honorable the East India Company's Press by P.P. Thoms ; published and sold by Kingsbury, Parbury, and Allen, Leadenhall Street. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- Part I, Vol. III - Robert Morrison (1823). A Dictionary of the Chinese Language, in Three Parts: Chinese and English, arranged according to the radicals. Macao, China: Printed at the Honorable the East India Company's Press by P.P. Thoms ; published and sold by Kingsbury, Parbury, and Allen, Leadenhall Street. p. 910. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- Part II, Vol. I - Robert Morrison (1819). A Dictionary of the Chinese Language, in Three Parts: Chinese and English arranged alphabetically. Macao, China: Printed at the Honorable the East India Company's Press by P.P. Thoms. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- Part II, Vol. II - Robert Morrison (1820). A Dictionary of the Chinese Language, in Three Parts: Chinese and English arranged alphabetically. Macao, China: Printed at the Honorable the East India Company's Press by P.P. Thoms ; published and sold by Black, Parbury, and Allen, Booksellers to the Honorable East India Company, London. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- Part III - Robert Morrison (1822). A Dictionary of the Chinese Language, in Three Parts: English and Chinese. Macao, China: Printed at the Honorable East India company's press, by P.P. Thoms. p. 214. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- Robert Morrison (1825). Chinese miscellany; consisting of original extracts from Chinese authors, in the native character. London: S. McDowall for the London Missionary Society. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- Morrison, Robert (1826). A Parting Memorial, consisting of Miscellaneous Discources. London: W Simpkin & R. Marshall.

- Robert Morrison (1828). Vocabulary of the Canton Dialect: Chinese words and phrases. Volume 3 of Vocabulary of the Canton Dialect. Macao, China: Printed at the Honorable East India company's press, by G.J. Steyn, and brother. Archived from the original on 6 February 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- Works by or about Robert Morrison at Internet Archive

- The Morrison Collection Bibliography

See also

- Morrison Academy

- Yung Wing

- Raffles Institution, the oldest school in Singapore, all-boys in Year 1-4 and co-ed in Year 5-6

- Ying Wa College, the world's first Anglo-Chinese school founded in 1818 by Morrison, now located in Hong Kong

Notes

- "In a country so extensive as China, and in which Tartars and Chinese are blended, it is in vain to expect a uniformity of pronunciation even amongst well educated people. The Тагиле are the rulers, and hence their pronunciation is imitated by many. The Chinese are the literary part of the community, and the systems of pronunciation found in books is often theirs. Some uniform system must be adopted, otherwise endless confusion will ensue. The pronunciation in this work, is rather what the Chinese call the Nanking dialect, than the Peking. The Peking dialect differs from it: lst. In changing k before e and i, into lch, and sometimes into ts; thus king becomes ching, and keäng becomes clœäng or tseäng. 2d. H before e and i, is turned into sfr: or s; thus hcäng is turned into sheäng, and heö into slwö, or seö. 3d. Chäng and tszìng are used for each other; also cho and tao, man and mwah., pan and pwzm, we and wei, are in the pronunciation of different persons confounded. 4th. The Tartars, and some people of the northern provinces, lengthen and soften the short tone; mnh becomes тоо. The short termination of М, becomes nearly the open sound..."[25]

References

Citations

- Wylie (1867), pp. 3–4

- "pioneering Scottish missionary Robert Morrison" (PDF). The Burke Library Archive. Columbia University Libraries. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- Thom, Robert (1840). Yishi Yuyan. Esop's Fables Written in Chinese by the Learned Mun Mooy Seen-Shang, and Compiled in their Present Form (With a free and literal translation) by His Pupil Sloth. Canton, China. p. Preface.

- Townsend (1890), appendix

- R. Li-Hua (2014). Competitiveness of Chinese Firms: West Meets East. Springer. p. 40. ISBN 9781137309303.

- West, Andrew. "The Morrison Collection: Robert Morrison: Biography". Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Horne (1904), ch. 5

- Daily. 2013

- Milne, William (1820). A retrospect of the first ten years of the Protestant mission to China. Anglo-Chinese Press. p. 65.

- "Old Protestant Cemetery in Macau" (PDF). Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- Scott, Gregory Adam; Kamsler, Brigette C. (February 2014). "Missionary Research Library Archives: D.W.C. Olyphant Papers, 1827–1851" (PDF). Columbia University Libraries. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- Townsend (1890), p. 203

- "Eastern Western Monthly Magazine (東西洋考每月統紀傳)" (in Chinese). Chinese Culture University, Taiwan. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- "Vol. 10 No. 31". Canton Register. Canton, China. 1 August 1837.

- Taylor, Charles (1860). Five Years in China. New York: J B McFerrin. p. 49. Observed on August 1848 visit by author

- "1920s Excavation of Morrison Hill". gwulo.com. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "Information on Public Swimming Pools: Morrison Hill Swimming Pool". Leisure and Cultural Services Department. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "Morrison Hall". University of Hong Kong. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- "STUDENT LEADER GROUPS". YMCA of Hong Kong Christian College. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "Declaration of the Morrison Building as a Monument" (PDF). Legislative Council of Hong Kong. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "Morrison Academy". Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- Daily, 2013.

- "Ying Wa College 200 Anniversary". Vincent's Calligraphy. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- Yang, Huiling (2014), "The Making of the First Chinese-English Dictionary: Robert Morrison's Dictionary of the Chinese Language in Three Parts (1815–1823)", Historiogrpahia Linguistica, Vol. 41, No. 2/3, pp. 299–322.

- Samuel Wells Williams (1844). English & Chinese vocabulary in the court dialect. Macao: Office of the Chinese Repository. p. xxvi.

- John T. P. Lai, Negotiating Religious Gaps: The Enterprise of Translating Christian Tracts by Protestant Missionaries in Nineteenth-Century China (Institut Monumenta Sérica, 2012). ISBN 978-3-8050-0597-5.

Bibliography

- Lai, John T. P. Negotiating Religious Gaps: The Enterprise of Translating Christian Tracts by Protestant Missionaries in Nineteenth-Century China (Institut Monumenta Sérica, 2012). ISBN 978-3-8050-0597-5.

- Hancock, Christopher (2008), Robert Morrison and the Birth of Chinese Protestantism (T&T Clark).

- Horne, C. Sylvester (1904). The Story of the L.M.S. London: London Missionary Society.

- Morrison, Eliza (1839). Memoirs of the life and labours of Robert Morrison (Vol.1) London : Orme, Brown, Green, and Longmans. -University of Hong Kong Libraries, Digital Initiatives, China Through Western Eyes

- Townsend, William (1890). Robert Morrison: the pioneer of Chinese missions. London: S.W. Partridge.

- Wylie, Alexander (1867). Memorials of Protestant Missionaries to the Chinese. Shanghai: American Presbyterian Mission Press.

- Ying, Fuk-Tsang. "Evangelist at the Gate: Robert Morrison's Views on Mission." Journal of Ecclesiastical History 63.2 (2012): 306–330.

Further reading

- The funeral discourse occasioned by the death of the Rev Robert Morrison ..., delivered before the London Missionary Society at the Poultry chapel, 19 February 1835. By Joseph Fletcher [1784–1843]. London : Frederick Westley and A. H. Davis, 1835. 75 p. { CWML G429 ; CWML G443 ; CWML N294 }

- Memoir of the Rev Robert Morrison, D.D., F.R.S., &c. By T.F. In The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register March 1835. { CWML O251 ; CWML N294 }

- Memoirs of the life and labours of Robert Morrison. Compiled by his widow [Eliza Morrison, 1795–1874], with critical notices of his Chinese works, by Samuel Kidd [1804–1843]. London : Longman, Orme, Brown, and Longmans, 1839. 2 v : ill, port ; 23 cm. { CWML Q122 }

- The origin of the first Protestant mission to China : and history of the events which induced the attempt, and succeeded in the accomplishment of a translation of the Holy Scriptures into the Chinese language, at the expense of the East India Company, and of the casualties which assigned to the late Dr Morrison the carrying out of this plan : with copies of the correspondence between the Archbishop of Canterbury ... &c and the Rev W. W. Moseley ... To which is appended a new account of the origin of the British and Foreign Bible Society, and a copy of the memoir which originated the Chinese mission &c. By William Willis Moseley. London : Simpkin and Marshall, 1842. [ii], 116 p. { CWML O86 ; CWML N310 }

- Robert Morrison : the pioneer of Chinese missions. By William John Townsend [1835–1915]. London : S.W. Partridge & Co., [ca.1890?]. 272 p. : ill, frontis. (port.) { CWML R427 }

- Cleaving the rock: the story of Robert Morrison, Christian pioneer in China. By T. Dixon Rutherford. London: London Missionary Society, [ca.1902?]. 24 p. : ill., ports. [New illustrated series of missionary biographies No.14] { CWML U233 }

- Robert Morrison and the centenary of Protestant missions in China : notes for speakers. London : London Missionary Society, 1907. [8] p. { CWML Q222 }

- Three typical missionaries. By Rev George J. Williams [1864–?]. [London] : London Missionary Society, [ca.1908?]. 8 p. [Outline missionary lessons for Sunday school teachers No.2] { CWML Q202 }

- Four lessons on Robert Morrison. By Vera E. Walker. [London] : London Missionary Society, [ca.1920?]. 15 p. : ill. { CWML Q244 }

- Robert Morrison, a master-builder. By Marshall Broomhall [1866–1937]. London, Livingstone Press, 1924. xvi, 238 p. ; front. (port.), 1 ill. (plan) ; 191⁄2 cm. { CWML U169 }

- Robert Morrison : China's pioneer. By Ernest Henry Hayes [1881–?]. London : Livingstone Press, 1925. 128 p.

- The years behind the wall. By Millicent and Margaret Thomas. London : Livingstone Press, 1936. 126 p. : ill. (some col.), frontis., maps on lining papers ; 20 cm. { CWML R449 }

- Robert Morrison : the scholar and the man. By Lindsay Ride [1898–1977]. Hong Kong (China) : Hong Kong University Press, 1957. vii, 48, [ii], 13, [12] p. : ill [Includes an illustrated catalogue of the exhibition held at the University of Hong Kong September 1957 to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Robert Morrison's arrival in China] { CWML M97 }

- The origins of the Anglo-American missionary enterprise in China, 1807–1840. By Murray A. Rubinstein [1942-]. Lanham, MD : Scarecrow Press, 1996. xi, 399 p. ; 23 cm. [ATLA monograph series no. 33] ISBN 0810827700

- Chuan jiao wei ren Ma-li-xun 傳教偉人馬禮遜. Written by Hai-en-bo 海恩波著 [Marshall Broomhall, 1866–1937]; translated by Jian Youwen (簡又文). Xiang-gang 香港 : Jidujiao wenyi chubanshe 基督教文藝出版社, 2000. 178 p., [4] p. of plates : ill. ; 21 cm. ISBN 9622944329 [Translation of Robert Morrison, a master-builder]

- Robert Morrison and the Protestant Plan for China. By Christopher A. Daily. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2013. 276 p. [Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland Book Series, distributed in N. America and Europe by Columbia University Press] ISBN 9789888208036

- Robert Morrison; Eliza Morrison (1839). Memoirs of the Life and Labours of Robert Morrison, D.D.: With Critical Notices of His Chinese Works ... and an Appendix Containing Original Documents. Volume One. Longman. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- Eliza A. Mrs. Robert Morrison (1839). Memoirs of the Life and Labours Robert Morrison. Volume Two. P. P. Thoms, Printer, Warwick Square: London: Longman, Orme, Brown, and Longmans. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Robert Morrison (missionary). |