Eugénie de Montijo

Doña María Eugenia Ignacia Agustina de Palafox y Kirkpatrick, 16th Countess of Teba, 15th Marchioness of Ardales (5 May 1826 – 11 July 1920), known as Eugénie de Montijo (French: [øʒeni də montiχo]), was the last empress of the French (1853–1870) as the wife of Emperor Napoleon III.

| Eugénie de Montijo | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16th Countess of Teba and 15th Marchioness of Ardales | |||||

The Empress Eugénie in 1862 | |||||

| Empress consort of the French | |||||

| Tenure | 30 January 1853 – 4 September 1870 | ||||

| Born | 5 May 1826 Granada, Kingdom of Spain | ||||

| Died | 11 July 1920 (aged 94) Madrid, Kingdom of Spain | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | Louis Napoléon, Prince Imperial | ||||

| |||||

| House | Bonaparte (by marriage) | ||||

| Father | Cipriano de Palafox y Portocarrero, 8th count of Montijo | ||||

| Mother | María Manuela Kirkpatrick de Grevignée | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholic | ||||

| Signature | |||||

Youth

The last empress of the French was born in Granada, Spain to Don Cipriano de Palafox y Portocarrero (1785–1839), Grandee, whose titles included 15th duke of Peñaranda de Duero, 8th count of Ablitas, 9th count of Montijo, 15th count of Teba, 8th count of Fuentidueña, 14th marquess of Ardales, 17th marquess of Moya and 13th marquess of la Algaba[1] and his half-Scottish, quarter-Belgian, quarter-Spanish wife (whom he married on 15 December 1817), María Manuela Enriqueta Kirkpatrick de Closbourn y de Grevigné (24 February 1794 – 22 November 1879), a daughter of the Scots-born William Kirkpatrick of Closeburn (1764–1837), who became United States consul to Málaga, and later was a wholesale wine merchant, and his wife, Marie Françoise de Grevigné (born 1769), daughter of Liège-born Henri, Baron de Grevigné and wife Doña Francisca Antonia de Gallegos (1751–1853).

Eugenia's older sister, María Francisca de Sales de Palafox Portocarrero y Kirkpatrick, nicknamed "Paca" (24 January 1825 – 16 September 1860), who inherited most of the family honours and was 12th duchess of Peñaranda Grandee of Spain and 9th countess of Montijo, title later ceded to her sister, married the 15th duke of Alba in 1849. Until her marriage in 1853, Eugénie variously used the titles of countess of Teba or countess of Montijo, but some family titles were inherited by her elder sister, through which they passed to the House of Alba. After the death of her father, Eugenia became the 9th countess of Teba, and is named as such in the Almanach de Gotha (1901 edition). After Eugenia's demise, all titles of the Montijo family came to the Fitz-Jameses (the dukes of Alba and Berwick).

On 18 July 1834, María Manuela and her daughters left Madrid for Paris, fleeing a cholera outbreak and the dangers of the First Carlist War. The previous day, Eugenia had witnessed a riot and murder in the square outside their residence, Casa Ariza.[2]

Eugénie de Montijo, as she became known in France, was formally educated mostly in Paris, beginning at the fashionable, traditionalist Convent of the Sacré Cœur from 1835 to 1836. A more compatible school was the progressive Gymnase Normal, Civil et Orthosomatique, from 1836 to 1837, which appealed to her athletic side (a school report praised her strong liking for athletic exercise, and although an indifferent student, that her character was "good, generous, active and firm").[3] In 1837, Eugénie and Paca briefly attended a boarding school for girls on Royal York Crescent in Clifton, Bristol,[4] to learn English. Eugénie was teased as "Carrots", for her red hair, and tried to run away to India, making it as far as climbing on board a ship at Bristol docks. In August 1837 they returned to school in Paris.[5] However, much of the girls' education took place at home, under the tutelage of English governesses Miss Cole and Miss Flowers,[6] and family friends such as Prosper Mérimée[7] and Henri Beyle.[8]

In March 1839, on the death of their father in Madrid, the girls left Paris to rejoin their mother there.[9] In Spain, Eugénie grew up into a headstrong and physically daring young woman, devoted to horseriding and a range of other sports.[10] She was rescued from drowning, and twice attempted suicide after romantic disappointments.[11] She was very interested in politics and became devoted to the Bonapartist cause, under the influence of Eleanore Gordon, a former mistress of Louis Napoléon.[10] Because her mother's role as a lavish society hostess, Eugénie became acquainted with Isabel II and the prime minister Ramón Narváez. María Manuela was increasingly anxious to find a husband for her daughter, and took her on trips to Paris again in 1849 and England in 1851.[12]

Empress

Marriage

.jpg)

She first met Prince Louis Napoléon after he had become president of the Second Republic with her mother at a reception given by the "prince-president" at the Élysée Palace on 12 April 1849.[13] "What is the road to your heart?" Napoleon demanded to know. "Through the chapel, Sire", she answered.[14]

In a speech on 22 January 1853, Napoleon III, after having become emperor, formally announced his engagement, saying "I have preferred a woman whom I love and respect to a woman unknown to me, with whom an alliance would have had advantages mixed with sacrifices".[15] They were wed on 29 January 1853 in a civil ceremony at the Tuileries, and on the 30th, there was a grander religious ceremony at Notre Dame.[16]

The marriage had come after considerable activity with regard to who would make a suitable match, often toward titled royals and with an eye to foreign policy. The final choice was opposed in many quarters and Eugénie considered of too little social standing by some.[17][18] In the United Kingdom, The Times made light of the latter concern, emphasizing that the parvenu Bonapartes were marrying into Grandees and one of the most important established houses in the peerage of Spain: "We learn with some amusement that this romantic event in the annals of the French Empire has called forth the strongest opposition, and provoked the utmost irritation. The Imperial family, the Council of Ministers, and even the lower coteries of the palace or its purlieus, all affect to regard this marriage as an amazing humiliation..."

Eugénie found childbearing extraordinarily difficult. An initial miscarriage in 1853, after a three-month pregnancy, frightened and soured her.[19] On 16 March 1856, after a two-day labor that endangered mother and child and from which Eugénie made a very slow recovery, the empress gave birth to an only son, Napoléon Eugène Louis Jean Joseph Bonaparte, styled Prince Impérial.[20][21]

After marriage, it didn't take long for her husband to stray as Eugénie found sex with him "disgusting".[22] It is doubtful that she allowed further approaches by her husband once she had given him an heir.[14] He subsequently resumed his "petites distractions" with other women.

Public life

Eugénie faithfully performed the duties of an empress, entertaining guests and accompanying the emperor to balls, opera, and theater. After her marriage, her ladies-in-waiting consisted of six (later 12) dames du palais, most of whom were chosen from among the acquaintances to the empress before her marriage, headed by the Grand-Maitresse Anne Debelle, Princesse d'Essling, and the dame d'honneur, Pauline de Bassano.[23]

She traveled to Egypt to open the Suez Canal and officially represented her husband whenever he traveled outside France. She strongly advocated equality for women; she pressured the Ministry of National Education to give the first baccalaureate diploma to a woman and tried unsuccessfully to induce the Académie française to elect the writer George Sand as its first female member.[24]

Her husband often consulted her on important questions, and she acted as regent during his absences in 1859, 1865 and 1870. In 1860, she visited Algiers with Napoleon.[25] A Catholic and a conservative, her influence countered any liberal tendencies in the emperor's policies.

She was a staunch defender of papal temporal powers in Italy and of ultramontanism. She was blamed for the fiasco of the French intervention in Mexico and the eventual death of Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico.[26] However, the assertion of her clericalism and influence on the side of conservatism is often countered by other authors.[27][28]

In 1868, Empress Eugénie visited the Dolmabahçe Palace in Constantinople, the home to Pertevniyal Sultan, mother of Abdülaziz, 32nd sultan of the Ottoman Empire. Pertevniyal became outraged by the forwardness of Eugénie taking the arm of one of her sons while he gave a tour of the palace garden, and she gave the empress a slap on the stomach as a reminder that they were not in France.[29] According to another account, Pertevniyal perceived the presence of a foreign woman within her quarters of the seraglio as an insult. She reportedly slapped Eugénie across the face, almost resulting in an international incident.[30]

Biarritz

In 1854, the Emperor Napoleon III and Eugénie bought several acres of dunes in Biarritz and gave the engineer Dagueret the task of establishing a summer home surrounded by gardens, woods, meadows, a pond and outbuildings.[31] Napoleon III chose the location near Spain so his wife would not get homesick for her native country.[32] The house was called the Villa Eugénie, today the Hôtel du Palais.[33] The presence of the imperial couple attracted other European royalty like the British monarchs Queen Victoria and the Spanish king Alfonso XIII and made Biarritz well-known.

Role in Franco-Prussian War

After the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, Eugénie remained in Paris as Regent while Napoleon III and the Prince Imperial travelled to join the troops at the German front. When the news of several French defeats reached Paris on 7 August, it was greeted with disbelief and dismay. Prime Minister Émile Ollivier and the chief of staff of the army, Marshal Le Bœuf both resigned and Eugenie took it upon herself to name a new government. She chose General Cousin-Montauban, better known as the count of Palikao, 74 years old, as her new prime minister. The count of Palikao named Maréchal Francois Achille Bazaine, the commander of the French forces in Lorraine, as the new overall military commander. Napoleon III proposed returning to Paris, realizing that he was doing no good for the army. The empress responded by telegraph: "Don't think of coming back, unless you want to unleash a terrible revolution. They will say you quit the army to flee the danger." The emperor agreed to remain with the army.[34] With the empress directing the country, and Bazaine commanding the army, the emperor no longer had any real role to play. At the front, the emperor told Marshal Le Bœuf "we've both been dismissed."[35]

The army was ultimately defeated and Napoleon III gave himself up to the Prussians at the Battle of Sedan. The news of the capitulation reached Paris on 3 September, and when it was given to the empress that the emperor and the army were prisoners, she reacted by shouting at the Emperor's personal aide "No! An emperor does not capitulate! He is dead!...They are trying to hide it from me. Why didn't he kill himself! Doesn't he know he has dishonored himself?!".[36] Later, when hostile crowds formed near the Tuileries palace, and the staff began to flee, the empress slipped out with one of her entourage and sought sanctuary with her American dentist, Thomas W. Evans, who took her to Deauville. From there, on 7 September, she took the yacht of a British official to England. In the meantime, on 4 September, a group of republican deputies proclaimed the return of the Republic, and the creation of a Government of National Defense.[37]

From 5 September 1870 until 19 March 1871, Napoleon III and his entourage including Joseph Bonaparte's grandson Louis Joseph Benton, were held in comfortable captivity in a castle at Wilhelmshöhe, near Kassel. Eugénie traveled incognito to Germany to visit Napoleon.[38]

After the Franco-Prussian War

When the Second Empire was overthrown after France's defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, the empress and her husband took permanent refuge in England, and settled at Camden Place in Chislehurst, Kent. Her husband, Napoleon III, died in 1873, and her son died in 1879 while fighting in the Zulu War in South Africa. In 1885, she moved to Farnborough, Hampshire, and to the Villa Cyrnos (named after the ancient Greek for Corsica), which was built for her at Cape Martin, between Menton and Nice, where she lived in retirement, abstaining from politics. Her house in Farnborough is now an independent Catholic girls' school, Farnborough Hill.[39]

After the deaths of her husband and son, as her health started to deteriorate, she spent some time at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight; her physician recommended she visit Bournemouth which was, in Victorian times, famed as a health spa resort. During her afternoon visit in 1881, she called on the queen of Sweden, at her residence 'Crag Head'.[40]

Her deposed family's friendly association with the United Kingdom was commemorated in 1887 when she became the godmother of Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg (1887–1969), daughter of Princess Beatrice, who later became queen consort of Alfonso XIII of Spain. She was also close to Empress Consort Alexandra Feodorovna of Russia, who last visited her, along with Emperor Nicholas II, in 1909.

On the outbreak of World War I, she donated her steam yacht Thistle to the British Navy. She funded a military hospital at Farnborough Hill as well as making large donations to French hospitals, for which she was conferred the Order of the British Empire (GBE) in 1919.[41]

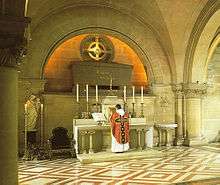

The former empress died in July 1920, aged 94, during a visit to her relative the 17th duke of Alba, at the Liria Palace in Madrid in her native Spain, and she is interred in the Imperial Crypt at St Michael's Abbey, Farnborough, with her husband and her son.

Eugenie lived long enough to see the collapse of other European monarchies after World War I, such as those of Russia, Germany and Austria-Hungary. She left her possessions to various relatives: her Spanish estates went to the grandsons of her sister Paca; the house in Farnborough with all collections to the heir of her son, Prince Victor Bonaparte; Villa Cyrnos to his sister Princess Laetitia of Aosta. Liquid assets were divided into three parts and given to the above relatives except the sum of 100,000 francs bequeathed to the Committee for Rebuilding the Cathedral of Reims.

Legacy

The empress has been commemorated in space; the asteroid 45 Eugenia was named after her,[42] and its moon Petit-Prince after the prince imperial.[43]

She had an extensive and unique jewelry collection,[44] most of which later was owned by the Brazilian socialite Aimée de Heeren.[45] De Heeren collected jewelry and was fond of the empress as both were considered to be the "Queens of Biarritz"; both spent summers on the Côte Basque. Impressed by the elegance, style and design of the jewelry of the neo-classical era, in 1858 she had a boutique in the Royal Palace under the name Royale Collections.

She was honoured by John Gould who gave the white-headed fruit dove the scientific name Ptilinopus eugeniae.

In popular culture

Named for the empress, the Eugénie hat is a style of women's chapeau worn dramatically tilted and drooped over one eye; its brim is folded up sharply at both sides in the style of a riding topper, often with one long ostrich plume streaming behind it.[46] The hat was popularized by film star Greta Garbo and enjoyed a vogue in the early 1930s, becoming "hysterically popular".[47] More representative of the empress' actual apparel, however, was the late 19th-century fashion of the Eugénie paletot, a women's greatcoat with bell sleeves and a single button enclosure at the neck.[48]

In the 1939 film Juarez, Eugenie was portrayed by Gale Sondergaard as a ruthless monarch, glad to help her husband in his scheme to control Mexico.

Honours

- 475th Dame of the Royal Order of Queen Maria Luisa of Spain, 6 March 1853[49]

- Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Isabel of Portugal, 1854[50]

- Grand Cross of the Order of St. Charles of Mexico, 1865[51]

- Honorary Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire, 1919[41]

Film portrayals

- In Suez (1938), Loretta Young plays her as the love interest of Ferdinand de Lesseps.

- In Juarez (1939), she was played by Gale Sondergaard, where she joins her husband in setting Austrian Archduke Maximilian on the throne of Mexico, and then abandons him.

- In Violetas Imperiales (1932, 1952): Set in 19th-century Granada, Eugénie de Montijo (played by Simone Valère) asks a gypsy girl, Violetta (played by Carmen Sevilla), to read her fortune in her hand. Emboldened by Violetta's prediction that she is to become a queen, Eugénie heads for Paris.

- In The Song of Bernadette (1943), she is played by Patricia Morison; she credits the waters of Lourdes with curing the prince imperial.

- In The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (2007), Emma de Caunes plays her during a fantasy sequence.

- In the miniseries Sisi (2009), she is portrayed by Hungarian actress Andrea Osvart.

Arms

- Heraldry of Empress Eugénie

Coat of Arms as empress of the French

Coat of Arms as empress of the French

(1853-1870).svg.png) Coat of Arms as dame of the Order of Queen María Luísa

Coat of Arms as dame of the Order of Queen María Luísa

(1853-1920)

See also

Citations

- "Cipriano Palafox y Portocarrero, 8. conde de Montijo". Geneall (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- Seward 2004, pp. 4–5.

- Kurtz 1964, pp. 16–18.

- Jones, Donald (1992). A History of Clifton. Chichester: Phillimore. p. 138. ISBN 0-85033-820-4.

- Seward 2004, p. 7.

- Kurtz 1964, p. 17.

- Kurtz 1964, pp. 13 et seq..

- Kurtz 1964, pp. 18 et seq..

- Seward 2004, pp. 11–12.

- Seward 2004, pp. 17–18.

- Seward 2004, pp. 20–22.

- Seward 2004, pp. 20–26.

- Kurtz 1964, p. 29.

- Bierman, M.F.E.M (1988). Napoleon III and His Carnival Empire. St Martin's Press (New York). ISBN 0-312-01827-4.

- Kurtz 1964, p. 50.

- Kurtz 1964, pp. 55–59.

- Duff 1978, pp. 83–84.

- Kurtz 1964, pp. 45–52.

- Duff 1978, pp. 104–105.

- Duff 1978, pp. 126–129.

- Kurtz 1964, pp. 90, 94.

- Kelen, Betty (1966). Mistresses: Domestic Scandals of 19th Century Monarchs. New York: Random Hours.

- Seward, Desmond: Eugénie. An empress and her empire. ISBN 0-7509-2979-0 (2004)

- Louis Napoléon Le Grand. pp. 204–210.

- "Interior of Governors Palace, Algiers, Algeria". World Digital Library. 1899. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- Maximilian and Carlota by Gene Smith, ISBN 0-245-52418-5, ISBN 978-0-245-52418-9

- Kurtz 1964.

- Filon 1920.

- Duff 1978, p. 191.

- "Women in Power" 1840–1870, entry: "1861–76 Pertevniyal Valide Sultan of The Ottoman Empire"

- Hôtel du Palais: Merimée.

- Prince & Porter 2010, p. 678.

- "Hotel du Palais, former Villa Eugenie". Grand Hotels of the World.

- Milza, 2009, pg. 80–81

- Milza, 2009, p. 81

- Milza, Pierre (2006). Napoleon III. Tempus (Paris). p. 711. ISBN 978-2-262-02607-3.

- Milza, Pierre (2006). Napoleon III. pp. 711–712.

- Girard, Louis (1986). Napoleon III. Tempus (Paris). p. 488. ISBN 2-01-27-9098-4.

- Farnborough Hill school website

- Bournemouth Visitors Directory 2 February 1881

- Seward 2004, pp. 293–294.

- Schmadel, Lutz D.; International Astronomical Union (2003). Dictionary of minor planet names. Berlin; New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 19. ISBN 978-3-540-00238-3. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- "Solar System Exploration: Asteroids – Moons". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. 2011. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- The Marguerite Necklace of Empress Eugenie

- Aimee de Heeren wearing the Marguerite Necklace Archived 10 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Calasibetta, Charlotte Mankey; Tortora, Phyllis (2010). The Fairchild Dictionary of Fashion (PDF). New York: Fairchild Books. pp. 249–250. ISBN 978-1-56367-973-5. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- Shields, Jody (1991). Hats: A Stylish History and Collector's Guide. New York: Clarkson Potter. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-517-57439-3.

- Calasibetta, p. 93.

- Real orden de Damas Nobles de la Reina Maria Luisa. Guía Oficial de España (in Spanish). 1887. p. 167. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- "Condecorações de Napoleão III" [Decorations of Napoleon III]. Academia Falerística de Portugal (in Portuguese). 3 February 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "Seccion IV: Ordenes del Imperio", Almanaque imperial para el año 1866 (in Spanish), 1866, p. 292, retrieved 29 April 2020

References

- Duff, David (1978). Eugenie and Napoleon III. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 0688033385.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Filon, Augustin (1920). Recollections of the Empress Eugénie. London: Cassell and Company, Ltd. Retrieved 14 August 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kurtz, Harold (1964). The Empress Eugénie: 1826–1920. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. LCCN 64006541.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Seward, Desmond (2004). Eugénie: The Empress and her Empire. Stroud: Sutton. ISBN 0-7509-29790.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Smith, Nancy (2017). Original Scarlett O'Hara: Similarity to the French Empress Eugenie who Impacted the Lincoln White House, Mexico, the Civil War and America's Gilded Age. Columbus: Biblio Publishing. ISBN 978-1622494064.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

![]()

- Eugenie de Montijo.com - The Empress of the French and Paris Les Halles

- Pronunciation of name by French speaker

- Newspaper clippings about Eugénie de Montijo in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

Eugénie de Montijo Born: 5 May 1826 Died: 11 July 1920 | ||

| French royalty | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vacant Title last held by Marie Amalie of the Two Siciliesas Queen of the French |

Empress of the French 30 January 1853–11 January 1871 |

Monarchy abolished |

| Titles in pretence | ||

| Vacant Title last held by Marie Louise of Austria |

— TITULAR — Empress of the French 11 January 1871 – 9 January 1873 Reason for succession failure: Empire replaced by Republic |

Vacant Title next held by Clémentine of Belgium |

| Spanish nobility | ||

| Preceded by Cipriano de Palafox y Portocarrero |

Countess of Teba 1839–1920 |

Succeeded by Eugenia María Fitz-James Stuart |

| Marchioness of Ardales 1839–1920 |

Succeeded by Jacobo Fitz-James Stuart | |