Dubrovnik

Dubrovnik (Croatian: [dǔbroːʋniːk] (![]()

Dubrovnik | |

|---|---|

| Grad Dubrovnik City of Dubrovnik | |

Top: old city of Dubrovnik, Second left: Sponza Palace, Second right: Rector's Palace, Third left: city walls, Third right: Dubrovnik Cathedral, Bottom: Stradun, the city's main street | |

Coat of arms | |

| Nicknames: "Pearl of the Adriatic", "Thesaurum mundi" | |

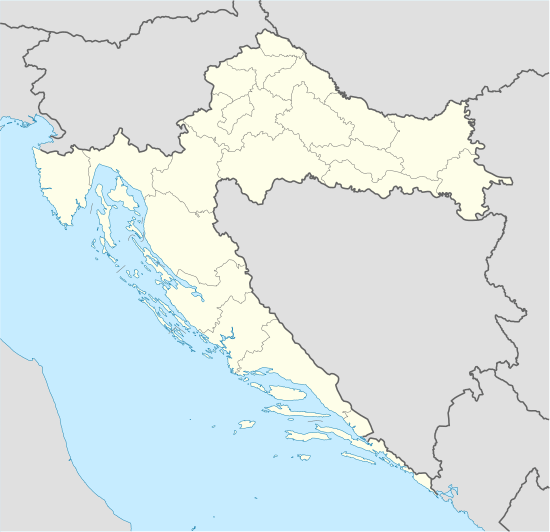

Dubrovnik The location of Dubrovnik within Croatia | |

| Coordinates: 42°38′25″N 18°06′30″E | |

| Country | |

| County | |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-Council |

| • Mayor | Mato Franković (HDZ) |

| • City Council | 25 members

|

| Area | |

| • City | 21.35 km2 (8.24 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 3 m (10 ft) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • City | 42,615 |

| • Density | 2,000/km2 (5,200/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 28,434 |

| • Metro | 65,808 |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | HR-20 000 |

| Area code(s) | +385 20 |

| Vehicle registration | DU |

| Patron saint | Saint Blaise |

| Website | www |

| Official name | Old City of Dubrovnik |

| Criteria | Cultural: (i)(iii)(iv) |

| Reference | 95 |

| Inscription | 1979 (3rd session) |

| Area | 96.7 ha (239 acres) |

.jpg)

The history of the city probably dates back to the 7th century, when the town known as Ragusa was founded by refugees from Epidaurum (Ragusa Vecchia). It was under the protection of the Byzantine Empire and later under the sovereignty of Republic of Venice. Between the 14th and 19th, Dubrovnik ruled itself as a free state. The prosperity of the city was historically based on maritime trade; as the capital of the maritime Republic of Ragusa, it achieved a high level of development, particularly during the 15th and 16th centuries, as it became notable for its wealth and skilled diplomacy. At the same time, Dubrovnik became a cradle of Croatian literature.

The entire city was almost destroyed when a devastating earthquake hit in 1667. During the Napoleonic Wars, Dubrovnik was occupied by the French Empire forces, and then the Republic of Ragusa was abolished and incorporated into the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy and later into Illyrian Provinces. During most of the 19th and 20th centuries, Dubrovnik was a part of the Austrian Empire, Austria-Hungary and Yugoslavia.

In 1991, during the disintegration of Yugoslavia, Dubrovnik was besieged by the Yugoslav People's Army for seven months and suffered significant damage from shelling. After undergoing repair and restoration works in the 1990s and early 2000s, it re-emerged as one of the Mediterranean's top tourist destinations, as well as a popular filming location, especially known for the HBO television series Game of Thrones.

Names

The names Dubrovnik and Ragusa co-existed for several centuries. Ragusa, recorded in various forms since at least the 10th century, remained the official name of the Republic of Ragusa until 1808, and of the city within the Kingdom of Dalmatia until 1918, while Dubrovnik, first recorded in the late 12th century, was in widespread use by the late 16th or early 17th century.[3]

The name Dubrovnik of the Adriatic city is first recorded in the Charter of Ban Kulin (1189).[4] It is mostly explained as dubron, a Celtic name for water (Gaulish dubron, Irish dobar, Welsh dŵr, dwfr, Cornish dofer), akin to the toponyms Douvres, Dover, and Tauber;[5] or originating from a Proto-Slavic word dǫbъ meaning 'oak'. The term dubrovnik means the 'oakwood', as in all other Slavic languages the word dub, dàb, means 'oak' and dubrava, dąbrowa means the 'oakwood'.

The historical name Ragusa is recorded in the Greek form Ῥαούσιν (Rhaousin, Latinized Ragusium) in the 10th century. It was recorded in various forms in the medieval period, Rausia, Lavusa, Labusa, Raugia, Rachusa. Various attempts have been made to etymologize the name. Suggestions include derivation from Greek ῥάξ, ῥαγός "grape"; from Greek ῥώξ, ῥωγός "narrow passage"; Greek ῥωγάς "ragged (of rocks)", ῥαγή (ῥαγάς) "fissure"; from the name of the Epirote tribe of the Rhogoi, from an unidentified Illyrian substrate. A connection to the name of Sicilian Ragusa has also been proposed. Putanec (1993) gives a review of etymological suggestion, and favours an explanation of the name as pre-Greek ("Pelasgian"), from a root cognate to Greek ῥαγή "fissure", with a suffix -ussa also found in the Greek name of Brač, Elaphousa.[6]

The classical explanation of the name is due to Constantine VII's De Administrando Imperio (10th century). According to this account, Ragusa (Ῥαούσιν) is the foundation of the refugees from Epidaurum (Ragusa Vecchia), a Greek city situated some 15 km (9 mi) to the south of Ragusa, when that city was destroyed in the Slavic incursions of the 7th century. The name is explained as a corruption of Lausa, the name of the rocky island on which the city was built (connected by Constantine to Greek λᾶας "rock, stone").

History

Origins

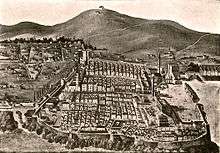

According to Constantine Porphyrogenitus's De Administrando Imperio (c. 950), Ragusa was founded in the 7th century, named after a "rocky island" called Lausa, by refugees from Epidaurum (Ragusa Vecchia), a Roman city situated some 15 km to the south, when that city was destroyed in the Slavic incursions.[7]

Excavations in 2007 revealed a Byzantine basilica from the 8th century and parts of the city walls. The size of the old basilica clearly indicates that there was quite a large settlement at the time. There is also evidence for the presence of a settlement in the pre-Christian era.[8]

Antun Ničetić, in his 1996 book Povijest dubrovačke luke ("History of the Port of Dubrovnik"), expounds the theory that Dubrovnik was established by Greek sailors, as a station halfway between the two Greek settlements of Budva and Korčula, 95 nautical miles (176 km; 109 mi) apart from each other.

Republic of Ragusa

After the fall of the Ostrogothic Kingdom, the town came under the protection of the Byzantine Empire. Dubrovnik in those medieval centuries had a Roman population.[9] In 12th and 13th centuries Dubrovnik became a truly oligarchic republic, and benefited greatly by becoming a commercial outpost for the rising and prosperous Serbian state, especially after the signing of a treaty with Stefan the First-Crowned.[10] After the Crusades, Dubrovnik came under the sovereignty of Venice (1205–1358), which would give its institutions to the Dalmatian city. In 1240, Ragusa purchased the island of Lastovo from Stefan Uroš I king of Serbia who had rights over the island as ruler of parts of Hum.[11] After a fire destroyed most of the city in the night of August 16, 1296, a new urban plan was developed.[12][13][14] By the Peace Treaty of Zadar in 1358, Dubrovnik achieved relative independence as a vassal-state of the Kingdom of Hungary. Ragusa experienced further expansion when, in 1333, Serbian emperor Stefan Dušan, sold Pelješac and Ston in exchange for cash and an annual tribute[15] at the moment when her connection with the rest of Europe, especially Italy, brought her into the full current of the Western Renaissance.[16]

Between the 14th century and 1808, Dubrovnik ruled itself as a free state, although it was a tributary from 1382 to 1804 of the Ottoman Empire and paid an annual tribute to its sultan.[17] The Republic reached its peak in the 15th and 16th centuries, when its thalassocracy rivalled that of the Republic of Venice and other Italian maritime republics.

For centuries, Dubrovnik was an ally of Ancona, the other Adriatic maritime republic rival of Venice, which was itself the Ottoman Empire's chief rival for control of the Adriatic. This alliance enabled the two towns set on opposite sides of the Adriatic to resist attempts by the Venetians to make the Adriatic a "Venetian Bay", also controlling directly or indirectly all the Adriatic ports. Ancona and Dubrovnik developed an alternative trade route to the Venetian (Venice-Austria-Germany): starting in Dubrovnik it went on to Ancona, through Florence and ended in Flanders as seen on this map.

The Republic of Ragusa received its own Statutes as early as 1272, which, among other things, codified Roman practice and local customs. The Statutes included prescriptions for town planning and the regulation of quarantine (for sanitary reasons).[18]

The Republic was an early adopter of what are now regarded as modern laws and institutions: a medical service was introduced in 1301, with the first pharmacy, still operating to this day, being opened in 1317. An almshouse was opened in 1347, and the first quarantine hospital (Lazarete) was established in 1377. Slave trading was abolished in 1418, and an orphanage opened in 1432. A 20 km (12 mi) water supply system, instead of a cistern, was constructed in 1438 by the Neapolitan architect and engineer Onofrio della Cava. He completed the aqueduct with two public fountains. He also built a number of mills along one of its branches.

The city was ruled by the local aristocracy which was of Latin-Dalmatian extraction and formed two city councils. As usual for the time, they maintained a strict system of social classes. The republic abolished the slave trade early in the 15th century and valued liberty highly. The city successfully balanced its sovereignty between the interests of Venice and the Ottoman Empire for centuries.

The languages spoken by the people were the Romance Dalmatian and common Croatian. The latter started to replace Dalmatian little by little from the 11th century among the common inhabitants of the city. Italian and Venetian would become important languages of culture and trade in Dubrovnik. At the same time, Dubrovnik became a cradle of Croatian literature.

The economic wealth of the Republic was partially the result of the land it developed, but especially of seafaring trade. With the help of skilled diplomacy, Dubrovnik merchants travelled lands freely and the city had a huge fleet of merchant ships (argosy) that travelled all over the world. From these travels they founded some settlements, from India to America, and brought parts of their culture and flora home with them. One of its keys to success was not conquering, but trading and sailing under a white flag with the Latin: Libertas word (freedom) prominently featured on it. The flag was adopted when slave trading was abolished in 1418.

Many Conversos, Jews from Spain and Portugal, were attracted to the city. In May 1544, a ship landed there filled exclusively with Portuguese refugees, as Balthasar de Faria reported to King John. During this time there worked in the city one of the most famous cannon and bell founders of his time: Ivan Rabljanin (Magister Johannes Baptista Arbensis de la Tolle). Already in 1571 Dubrovnik sold its protectorate over some Christian settlements in other parts of the Ottoman Empire to France and Venice. At that time there was also a colony of Dubrovnik in Fes in Morocco. The bishop of Dubrovnik was a Cardinal protector in 1571. At that time there were only 16 other countries which had Cardinal protectors; those being France, Spain, Austria, Portugal, Poland, England, Scotland, Ireland, Naples, Sicily, Sardinia, Savoy, Lucca, Greece, Illyria, Armenia and Lebanon.

The Republic gradually declined due to a combination of a Mediterranean shipping crisis and the catastrophic earthquake of 1667[19] which killed over 5,000 citizens, levelled most of the public buildings and, consequently, negatively affected the well-being of the Republic. In 1699, the Republic was forced to sell two mainland patches of its territory to the Ottomans in order to avoid being caught in the clash with advancing Venetian forces. Today this strip of land belongs to Bosnia and Herzegovina and is that country's only direct access to the Adriatic. A highlight of Dubrovnik's diplomacy was the involvement in the American Revolution.[20]

On 27 May 1806, the forces of the Empire of France occupied the neutral Republic of Ragusa. Upon entering Ragusan territory without permission and approaching the capital, the French General Jacques Lauriston demanded that his troops be allowed to rest and be provided with food and drink in the city before continuing on to take possession of their holdings in the Bay of Kotor. However, this was a deception because as soon as they entered the city, they proceeded to occupy it in the name of Napoleon.[21] Almost immediately after the beginning of the French occupation, Russian and Montenegrin troops entered Ragusan territory and began fighting the French army, raiding and pillaging everything along the way and culminating in a siege of the occupied city (during which 3,000 cannonballs fell on the city).[22] In 1808 Marshal Marmont issued a proclamation abolishing the Republic of Ragusa and amalgamating its territory into the French Empire's client state, the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy. Marmont claimed the newly created title of "Duke of Ragusa" (Duc de Raguse) and in 1810 Ragusa, together with Istria and Dalmatia, went to the newly created French Illyrian Provinces.

After seven years of French occupation, encouraged by the desertion of French soldiers after the failed invasion of Russia and the reentry of Austria in the war, all the social classes of the Ragusan people rose up in a general insurrection, led by the patricians, against the Napoleonic invaders.[23] On 18 June 1813, together with British forces they forced the surrender of the French garrison of the island of Šipan, soon also the heavily fortified town of Ston and the island of Lopud, after which the insurrection spread throughout the mainland, starting with Konavle.[24] They then laid siege to the occupied city, helped by the British Royal Navy, who had enjoyed unopposed domination over the Adriatic sea, under the command of Captain William Hoste, with his ships HMS Bacchante and HMS Saracen. Soon the population inside the city joined the insurrection.[25] The Austrian Empire sent a force under General Todor Milutinović offering to help their Ragusan allies.[26] However, as was soon shown, their intention was to in fact replace the French occupation of Ragusa with their own. Seducing one of the temporary governors of the Republic, Biagio Bernardo Caboga, with promises of power and influence (which were later cut short and who died in ignominy, branded as a traitor by his people), they managed to convince him to keep the gate to the east closed to the Ragusan forces and to let Austrian forces enter the City from the west, once the French garrison of 500 troops under General Joseph de Montrichard had surrendered.[27]

After this, the Flag of Saint Blaise was flown alongside the Austrian and British colors, but only for two days because, on 30 January, General Milutinović ordered Mayor Sabo Giorgi to lower it. Overwhelmed by a feeling of deep patriotic pride, Giorgi, the last Rector of the Republic, refused to do so "for the masses had hoisted it". Subsequent events proved that Austria took every possible opportunity to invade the entire coast of the eastern Adriatic, from Venice to Kotor. The Austrians did everything in their power to eliminate the Ragusa issue at the Congress of Vienna. Ragusan representative Miho Bona, elected at the last meeting of the Major Council, was denied participation in the Congress, while Milutinović, prior to the final agreement of the allies, assumed complete control of the city.[28]:141–142

Regardless of the fact that the government of the Ragusan Republic never signed any capitulation nor relinquished its sovereignty, which according to the rules of Klemens von Metternich that Austria adopted for the Vienna Congress should have meant that the Republic would be restored, the Austrian Empire managed to convince the other allies to allow it to keep the territory of the Republic.[29] While many smaller and less significant cities and former countries were permitted an audience, that right was refused to the representative of the Ragusan Republic.[30] All of this was in blatant contradiction to the solemn treaties that the Austrian Emperors signed with the Republic: the first on 20 August 1684, in which Leopold I promises and guarantees inviolate liberty ("inviolatam libertatem") to the Republic, and the second in 1772, in which the Empress Maria Theresa promises protection and respect of the inviolability of the freedom and territory of the Republic.[31].

Languages

The official language until 1472 was Latin. As a consequence of the increasing migration of Slavic population from inland Dalmatia, the language spoken by much of the population was Croatian, typically referred to in Dubrovnik's historical documents simply as "Slavic". To oppose the demographics change due to increased Slavic immigration from the Balkans, the native Romance population of Ragusa, which made up the oligarchic government of the Republic, tried to prohibit the use of any Slavic languages in official councils.[32] Archeologists have also discovered medieval Glagolitic tablets near Dubrovnik, such as the inscription of Župa Dubrovačka, indicating that the Glagolitic script was also likely once used in the city.

The Italian language as spoken in the republic was heavily influenced by the Venetian language and the Tuscan dialect. Italian took root among the Dalmatian-speaking merchant upper classes, as a result of Venetian influence which strengthened the original Latin element of the population.[33][34]

Austrian rule

When the Habsburg Empire annexed these provinces after the 1815 Congress of Vienna, the new authorities implemented a bureaucratic administration, established the Kingdom of Dalmatia, which had its own Sabor (Diet) or Parliament which is the oldest Croatian political institution based in the city of Zadar, and political parties such as the Autonomist Party and the People's Party. They introduced a series of modifications intended to slowly centralise the bureaucratic, tax, religious, educational, and trade structure. These steps largely failed, despite the intention of wanting to stimulate the economy. Once the personal, political and economic damage of the Napoleonic Wars had been overcome, new movements began to form in the region, calling for a political reorganisation of the Adriatic along national lines.

The combination of these two forces—a flawed Habsburg administrative system and new national movement claiming ethnicity as the founding block toward a community—posed a particularly perplexing problem: Dalmatia was a province ruled by the German-speaking Habsburg monarchy, with bilingual (Serbo-Croatian- and Italian-speaking) elites that dominated the general population consisting of a Slavic Catholic majority, as well as a Slavic Orthodox minority. Further complicating matters was the reality that increased emphases on ethnic identification in the nineteenth century did not break down along religious lines, as evident in the Serb-Catholic movement in Dubrovnik.

In 1815, the former Dubrovnik Government (its noble assembly) met for the last time in Ljetnikovac in Mokošica. Once again, extreme measures were taken to re-establish the Republic, but it was all in vain. After the fall of the Republic most of the aristocracy was recognised by the Austrian Empire.

In 1832, Baron Šišmundo Getaldić-Gundulić (Sigismondo Ghetaldi-Gondola) (1795–1860) was elected Mayor of Dubrovnik, serving for 13 years; the Austrian government granted him the title of "Baron".

Count Rafael Pucić (Raffaele Pozza), (1828–1890) was elected for first time Podestà of Dubrovnik in the year 1869 after this was re-elected in 1872, 1875, 1882, 1884) and elected twice into the Dalmatian Council, 1870, 1876. The victory of the Nationalists in Split in 1882 strongly affected in the areas of Korčula and Dubrovnik. It was greeted by the mayor (podestà) of Dubrovnik Rafael Pucić, the National Reading Club of Dubrovnik, the Workers Association of Dubrovnik and the review "Slovinac"; by the communities of Kuna and Orebić, the latter one getting the nationalist government even before Split.

In 1889, the Serb-Catholics circle supported Baron Francesco Ghetaldi-Gondola, the candidate of the Autonomous Party, vs the candidate of Popular Party Vlaho de Giulli, in the 1890 election to the Dalmatian Diet.[35] The following year, during the local government election, the Autonomous Party won the municipal re-election with Francesco Gondola, who died in power in 1899. The alliance won the election again on 27 May 1894. Frano Getaldić-Gundulić founded the Società Philately on 4 December 1890.

In 1905, the Committee for establishing electric tram service, headed by Luko Bunić – certainly one of the most deserving persons who contributed to the realisation of the project – was established. Other members of the Committee were Ivo Papi, Miho Papi, Artur Saraka, Mato Šarić, Antun Pugliesi, Mato Gracić, Ivo Degiulli, Ernest Katić and Antun Milić.[36] The tram service in Dubrovnik existed from 1910 to 1970.

Pero Čingrija (1837–1921), one of the leaders of the People's Party in Dalmatia,[37] played the main role in the merger of the People's Party and the Party of Right into a single Croatian Party in 1905.

Yugoslav period (1918–1991)

With the fall of Austria–Hungary in 1918, the city was incorporated into the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia). Dubrovnik became one of the 33 oblasts of the Kingdom. When in 1929 Yugoslavia was divided among 9 Banovina, the city became part of the Zeta Banovina. In 1939 Dubrovnik became part of the newly created Banovina of Croatia.

During World War II, Dubrovnik became part of the Nazi-puppet Independent State of Croatia, occupied by the Italian army first, and by the German army after 8 September 1943. In October 1944 Yugoslav Partisans occupied Dubrovnik, arresting more than 300 citizens and executing 53 without trial; this event came to be known, after the small island on which it occurred, as the Daksa Massacre.[38] Communist leadership during the next several years continued political prosecutions, which culminated on 12 April 1947 with the capture and imprisonment of more than 90 citizens of Dubrovnik.[39]

Under communism Dubrovnik became part of the Socialist Republic of Croatia and Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. After the second world war, the city started to attract crowds of tourists - even more after 1979, when the city joined the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites. The growth of tourism also led to the decision to demilitarise the Old Town of Dubrovnik. The income from tourism was pivotal in the post-war development of the city, including its airport.[40] The Dubrovnik Summer Festival started being held in 1950.[41] The "Adriatic Highway" (Magistrala) was opened in 1965 after a decade of works, connecting Dubrovnik with Rijeka along the whole coastline, and giving a boost to the touristification of the Croatian riviera.[42]

A villa on Dubrovnik’s Lapad peninsula was nationalised and used by Tito; after a 12-year battle for restitution, it was given back to the original owners, the Banac family. It now belongs to a Croatian entrepreneur.[43]

Since 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia and its aftermath

.jpg)

In 1991 Croatia and Slovenia, which at that time were republics within Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, declared their independence. At that event, Socialist Republic of Croatia was renamed Republic of Croatia.

Despite the demilitarisation of the old town in early 1970s in an attempt to prevent it from ever becoming a casualty of war, following Croatia's independence in 1991 Yugoslavia's Yugoslav People's Army (JNA), by then composed primarily of Serbs, attacked the city. The new Croatian government set up a military outpost in the city itself. Montenegro, led by president Momir Bulatović, and prime minister Milo Đukanović, coming to power in the Anti-bureaucratic revolution and allied to Slobodan Milošević in Serbia, declared that Dubrovnik should not remain in Croatia because they claimed it historically had never been part of an independent Croatia, but rather more historically aligned with the coastal history of Montenegro. Be that as it may, at the time most residents of Dubrovnik had come to identify as Croatian, with self-identified Serbs accounting for 6.8 percent of the population.[44]

On October 1, 1991 Dubrovnik was attacked by JNA with a siege of Dubrovnik that lasted for seven months. The heaviest artillery attack was on December 6 with 19 people killed and 60 wounded. The number of casualties in the conflict, according to Croatian Red Cross, was 114 killed civilians, among them poet Milan Milišić. Foreign newspapers were criticised for placing heavier attention on the damage suffered by the old town than on human casualties.[45] Nonetheless, the artillery attacks on Dubrovnik damaged 56% of its buildings to some degree, as the historic walled city, a UNESCO world heritage site, sustained 650 hits by artillery rounds.[46] The Croatian Army lifted the siege in May 1992, and liberated Dubrovnik's surroundings by the end of October, but the danger of sudden attacks by the JNA lasted for another three years.[47]

Following the end of the war, damage caused by the shelling of the Old Town was repaired. Adhering to UNESCO guidelines, repairs were performed in the original style. Most of the reconstruction work was done between 1995 and 1999.[48] The inflicted damage can be seen on a chart near the city gate, showing all artillery hits during the siege, and is clearly visible from high points around the city in the form of the more brightly coloured new roofs. ICTY indictments were issued for JNA generals and officers involved in the bombing.

General Pavle Strugar, who coordinated the attack on the city, was sentenced to a seven-and-a-half-year prison term by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia for his role in the attack.[49]

The 1996 Croatia USAF CT-43 crash, near Dubrovnik Airport, killed everyone on a United States Air Force jet with United States Secretary of Commerce Ron Brown, The New York Times Frankfurt Bureau chief Nathaniel C. Nash and 33 other people.

Geography

Climate

| Dubrovnik (Dubrovnik, City of Dubrovnik) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dubrovnik has a borderline humid subtropical (Cfa) and Mediterranean climate (Csa) in the Köppen climate classification, since only one summer month has less than 40 mm (1.6 in) of rainfall, preventing it from being classified as solely humid subtropical or Mediterranean. Dubrovnik has hot, muggy, moderately dry summers and mild to cool wet winters. The bora wind blows cold gusts down the Adriatic coast between October and April, and thundery conditions are common all the year round, even in summer, when they interrupt the warm, sunny days. The air temperatures can slightly vary, depending on the area or region. Typically, in July and August daytime maximum temperatures reach 28 °C (82 °F), and at night drop to around 23 °C (73 °F). In Spring and Autumn maximum temperatures are typically between 20 °C (68 °F) and 28 °C (82 °F). Winters are among the mildest of any Croatian city, with daytime temperatures around 13 °C (55 °F) in the coldest months. Snow in Dubrovnik is very rare.

- Air temperature

- average annual: 16.4 °C (61.5 °F)

- average of coldest period: January, 10 °C (50 °F)

- average of warmest period: August, 25.8 °C (78.4 °F)

- Sea temperature

- average May–September: 18.7–25.5 °C (65.7–77.9 °F)

- Salinity

- approximately 3.8%

- Precipitation

- average annual: 1,020.8 mm (40.19 in)

- average annual rain days: 109.2

- Sunshine

- average annual: 2629 hours

- average daily hours: 7.2 hours

| Climate data for Dubrovnik (1971–2000, extremes 1961–2019) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.4 (65.1) |

24.1 (75.4) |

26.8 (80.2) |

30.2 (86.4) |

32.9 (91.2) |

37.3 (99.1) |

37.9 (100.2) |

38.4 (101.1) |

33.5 (92.3) |

30.5 (86.9) |

25.4 (77.7) |

20.3 (68.5) |

38.4 (101.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 12.3 (54.1) |

12.6 (54.7) |

14.4 (57.9) |

16.9 (62.4) |

21.5 (70.7) |

25.3 (77.5) |

28.2 (82.8) |

28.5 (83.3) |

25.1 (77.2) |

21.1 (70.0) |

16.6 (61.9) |

13.4 (56.1) |

19.7 (67.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.2 (48.6) |

9.4 (48.9) |

11.1 (52.0) |

13.8 (56.8) |

18.3 (64.9) |

22.0 (71.6) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.8 (76.6) |

21.4 (70.5) |

17.6 (63.7) |

13.3 (55.9) |

10.3 (50.5) |

16.3 (61.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 6.6 (43.9) |

6.8 (44.2) |

8.4 (47.1) |

11.0 (51.8) |

15.3 (59.5) |

18.9 (66.0) |

21.4 (70.5) |

21.6 (70.9) |

18.4 (65.1) |

14.9 (58.8) |

10.7 (51.3) |

7.8 (46.0) |

13.5 (56.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.0 (19.4) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

1.6 (34.9) |

5.2 (41.4) |

10.0 (50.0) |

14.1 (57.4) |

14.1 (57.4) |

8.5 (47.3) |

4.5 (40.1) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 98.3 (3.87) |

97.9 (3.85) |

93.1 (3.67) |

91.4 (3.60) |

70.1 (2.76) |

44.0 (1.73) |

28.3 (1.11) |

72.5 (2.85) |

86.1 (3.39) |

120.1 (4.73) |

142.3 (5.60) |

119.8 (4.72) |

1,064 (41.89) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 11.2 | 11.2 | 11.2 | 12.0 | 9.4 | 6.4 | 4.7 | 5.1 | 7.2 | 10.8 | 12.4 | 12.0 | 113.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 59.9 | 58.4 | 61.2 | 64.2 | 66.7 | 63.8 | 58.2 | 59.2 | 61.9 | 62.2 | 62.4 | 60.3 | 61.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 130.2 | 142.8 | 179.8 | 207.0 | 266.6 | 312.0 | 347.2 | 325.5 | 309.0 | 189.1 | 135.0 | 124.0 | 2,668.2 |

| Source: Croatian Meteorological and Hydrological Service[50][51] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Dubrovnik | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °C (°F) | 14.1 (57.4) |

14.2 (57.6) |

14.4 (57.9) |

15.6 (60.1) |

18.7 (65.7) |

23.1 (73.6) |

25.5 (77.9) |

25.4 (77.7) |

24.3 (75.7) |

20.7 (69.3) |

18.2 (64.8) |

15.7 (60.3) |

19.2 (66.5) |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 9.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 14.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 12.2 |

| Average Ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4.8 |

| Source: Weather Atlas[52] | |||||||||||||

Heritage

| Old City of Dubrovnik | |

|---|---|

| Native name Croatian: Stari grad Dubrovnik | |

The Old Harbour at Dubrovnik | |

| Location | Dubrovnik-Neretva County, Croatia |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iii, iv |

| Designated | 1979 (3rd Session) |

| Reference no. | 95 |

| Extension | 1994 |

| Endangered | 1991–1998 |

| Official name: Stari grad Dubrovnik | |

The annual Dubrovnik Summer Festival is a 45-day-long cultural event with live plays, concerts, and games. It has been awarded a Gold International Trophy for Quality (2007) by the Editorial Office in collaboration with the Trade Leaders Club.

The patron saint of the city is Sveti Vlaho (Saint Blaise), whose statues are seen around the city. He has an importance similar to that of St. Mark the Evangelist to Venice. One of the larger churches in city is named after Saint Blaise. February 3 is the feast of Sveti Vlaho (Saint Blaise), who is the city's patron saint. Every year the city of Dubrovnik celebrates the holiday with Mass, parades, and festivities that last for several days.[53]

The Old Town of Dubrovnik is depicted on the reverse of the Croatian 50 kuna banknote, issued in 1993 and 2002.[54]

The city boasts many old buildings, such as the Arboretum Trsteno, the oldest arboretum in the world, which dates back to before 1492. Also, the third-oldest European pharmacy and the oldest still in operation, having been founded in 1317, is in Dubrovnik, at the Little Brothers monastery.[55]

In history, many Conversos (Marranos) were attracted to Dubrovnik, formerly a considerable seaport. In May 1544, a ship landed there filled exclusively with Portuguese refugees, as Balthasar de Faria reported to King John. Another admirer of Dubrovnik, George Bernard Shaw, visited the city in 1929 and said: "If you want to see heaven on earth, come to Dubrovnik."[56][57]

In the bay of Dubrovnik is the 72-hectare (180-acre) wooded island of Lokrum, where according to legend, Richard the Lionheart, King of England, was cast ashore after being shipwrecked in 1192. The island includes a fortress, botanical garden, monastery and naturist beach.

Among the many tourist destinations are a few beaches. Banje, Dubrovnik's main public beach, is home to the Eastwest Beach Club. There is also Copacabana Beach, a stony beach on the Lapad peninsula,[58] named after the popular beach in Rio de Janeiro.

By 2018, the city had to take steps to reduce the excessive number of tourists, especially in the Old Town. One method to moderate the overcrowding was to stagger the arrival/departure times of cruise ships to spread the number of visitors more evenly during the week.[59]

Important monuments

Few of Dubrovnik's Renaissance buildings survived the earthquake of 1667 but enough remained to give an idea of the city's architectural heritage.[60] The finest Renaissance highlight is the Sponza Palace which dates from the 16th century and is currently used to house the National Archives.[61] The Rector's Palace is a Gothic-Renaissance structure that displays finely carved capitals and an ornate staircase. It now houses a museum.[62][63] Its façade is depicted on the reverse of the Croatian 50 kuna banknote, issued in 1993 and 2002.[54] The St. Saviour Church is another remnant of the Renaissance period, next to the much-visited Franciscan Church and Monastery.[55][64][65] The Franciscan monastery's library possesses 30,000 volumes, 216 incunabula, 1,500 valuable handwritten documents. Exhibits include a 15th-century silver-gilt cross and silver thurible, and an 18th-century crucifix from Jerusalem, a martyrology (1541) by Bemardin Gucetic and illuminated psalters.[55]

Dubrovnik's most beloved church is St Blaise's church, built in the 18th century in honour of Dubrovnik's patron saint. Dubrovnik's Baroque Cathedral was built in the 18th century and houses an impressive Treasury with relics of Saint Blaise. The city's Dominican Monastery resembles a fortress on the outside but the interior contains an art museum and a Gothic-Romanesque church.[66][67] A special treasure of the Dominican monastery is its library with 216 incunabula, numerous illustrated manuscripts, a rich archive with precious manuscripts and documents and an extensive art collection.[68][69][70]

The Neapolitan architect and engineer Onofrio della Cava completed the aqueduct with two public fountains, both built in 1438. Close to the Pile Gate stands the Big Onofrio's Fountain in the middle of a small square. It may have been inspired by the former Romanesque baptistry of the former cathedral in Bunić Square. The sculptural elements were lost in the earthquake of 1667. Water jets gush out of the mouth of the sixteen mascarons. The Little Onofrio's Fountain stands at the eastern side of the Placa, supplying water the market place in the Luža Square. The sculptures ware made by the Milanese artist Pietro di Martino (who also sculpted the ornaments in the Rector's Palace and made a statue – now lost – for the Franciscan church).

The 31-metre-high (102 ft) Dubrovnik Bell Tower, built in 1444, is one of the symbols of the free city state of Ragusa. It was built by the local architects Grubačević, Utišenović and Radončić. It was rebuilt in 1929 as it had lost its stability through an earthquake and was in danger of falling. The brass face of the clock shows the phases of the moon. Two human figures strike the bell every hour. The tower stands next to the House of the Main Guard, also built in Gothic style. It was the residence of the admiral, commander-in-chief of the army. The Baroque portal was built between 1706 and 1708 by the Venetian architect Marino Gropelli (who also built St Blaise's church).

In 1418, the Republic of Ragusa, as Dubrovnik was then named, erected a statue of Roland (Ital. Orlando) as a symbol of loyalty to Sigismund of Luxembourg (1368–1437), King of Hungary and Croatia (as of 1387), Prince-Elector of Brandenburg (between 1378 and 1388 and again between 1411 and 1415), German King (as of 1411), King of Bohemia (as of 1419) and Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire (as of 1433), who helped by a successful war alliance against Venice to retain Ragusa's independence. It stands in the middle of Luža Square. Roland statues were typical symbols of city autonomy or independence, often erected under Sigismund in his Electorate of Brandenburg. In 1419 the sculptor Bonino of Milano, with the help of local craftsmen, replaced the first Roland with the present Gothic statue. Its forearm was for a long time the unit of measure in Dubrovnik: one ell of Dubrovnik is equal to 51.2 cm (20.2 in).

Saint Blaise's Church

Saint Blaise's Church Saint Ignatius Church

Saint Ignatius Church Cathedral of the Assumption

Cathedral of the Assumption The Franciscan Monastery

The Franciscan Monastery- Rector's Palace

Stradun, Dubrovnik's main street

Stradun, Dubrovnik's main street The Clock tower

The Clock tower

Walls of Dubrovnik

A feature of Dubrovnik is its walls (1.3 million visitors in 2018), which run almost 2 kilometres (1.2 miles) around the city. The walls are 4 to 6 metres (13–20 feet) thick on the landward side but are much thinner on the seaward side. The system of turrets and towers were intended to protect the vulnerable city. The walls of Dubrovnik have also been a popular filming location for the fictional city of King's Landing in the HBO television series, Game of Thrones.[71]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 15,666 | — |

| 1890 | 15,329 | −2.2% |

| 1900 | 17,384 | +13.4% |

| 1910 | 18,396 | +5.8% |

| 1921 | 16,719 | −9.1% |

| 1931 | 20,420 | +22.1% |

| 1948 | 21,778 | +6.7% |

| 1953 | 24,296 | +11.6% |

| 1961 | 27,793 | +14.4% |

| 1971 | 35,628 | +28.2% |

| 1981 | 46,025 | +29.2% |

| 1991 | 51,597 | +12.1% |

| 2001 | 43,770 | −15.2% |

| 2011 | 42,615 | −2.6% |

| Source: Naselja i stanovništvo Republike Hrvatske 1857–2001, DZS, Zagreb, 2005 | ||

The total population of the city is 42,615 (census 2011), in the following settlements:[1]

- Bosanka, population 139

- Brsečine, population 96

- Čajkovica, population 160

- Čajkovići, population 26

- Donje Obuljeno, population 210

- Dubravica, population 37

- Dubrovnik, population 28,434

- Gornje Obuljeno, population 124

- Gromača, population 146

- Kliševo, population 54

- Knežica, population 133

- Koločep, population 163

- Komolac, population 320

- Lopud, population 249

- Lozica, population 146

- Ljubač, population 69

- Mokošica, population 1,924

- Mravinjac, population 88

- Mrčevo, population 90

- Nova Mokošica, population 6,016

- Orašac, population 631

- Osojnik, population 301

- Petrovo Selo, population 23

- Pobrežje, population 118

- Prijevor, population 453

- Rožat, population 340

- Suđurađ, population 207

- Sustjepan, population 323

- Šipanska Luka, population 211

- Šumet, population 176

- Trsteno, population 222

- Zaton, population 985

The population was 42,615 in 2011,[1] down from 49,728 in 1991[72] In the 2011 census, 90.34% of the population identified as Croat.[73]

Transport

Dubrovnik has its own international airport, located approximately 20 km (12 mi) southeast of Dubrovnik city centre, near Čilipi. Buses connect the airport with the Dubrovnik old main bus station in Gruž. In addition, a network of modern, local buses connects all Dubrovnik neighbourhoods running frequently from dawn to midnight. However, Dubrovnik, unlike Croatia's other major centres, is not accessible by rail;[75] until 1975 Dubrovnik was connected to Mostar and Sarajevo by a narrow gauge railway (760 mm)[76][77] built during the Austro-Hungarian rule of Bosnia.

The A1 highway, in use between Zagreb and Ploče, is planned to be extended all the way to Dubrovnik. Because the area around the city is disconnected from the rest of Croatian territory, the highway will either cross the Pelješac Bridge whose construction is in preparation as of 2018,[78] or run through Neum in Bosnia and Herzegovina and continue to Dubrovnik.

Education

Dubrovnik has a number of higher educational institutions. These include the University of Dubrovnik, the Libertas University (Dubrovnik International University), Rochester Institute of Technology Croatia (former American College of Management and Technology), a University Centre for Postgraduate Studies of the University of Zagreb, and an Institute of History of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts.

Sports

The city will host the 2025 World Men's Handball Championship at the new arena, along with the countries Denmark and Norway.

Panoramas

Panoramic view of Dubrovnik

Notable people

- Franco Sacchetti (Ragusa, 1332 – San Miniato, 1400), poet and novelist

- Benedetto Cotrugli (Ragusa, 1416 – L'Aquila, 1469), humanist and economist.

- Bonino de Boninis (Lastovo, Ragusa, 1454 – Treviso, 1528), typographist and bookseller.

- Elio Lampridio Cerva (Ragusa, 1463 – 1520), humanist, poet and lexicographer of Latin language

- Marin Držić (Ragusa, 1508 – Venice, 1567), playwright, poet and dramaturge

- Marino Ghetaldi (Ragusa, 1568 – 1626), mathematician

- Giorgio Raguseo (Ragusa, 1580 – 1622), philosopher, theologian, and orator

- Rajmund Zamanja (Ragusa, 1587 – Ragusa, 1647), theologist, philosopher and linguist.

- Ivan Gundulić (Ragusa, 1589 – 1638), writer and poet

- Anselmo Banduri (Ragusa, 1671 – Paris, 1743), numismatist and antiquarian

- Ruđer Josip Bošković (Dubrovnik, 1711 – Milan, 1787) physicist, astronomer, mathematician, philosopher, diplomat, poet, theologian

- Mato Vodopić (Dubrovnik, 1816), bishop of Dubrovnik

- Matija Ban (Dubrovnik, 1818), poet, dramatist, and playwright

- Medo Pucić (Dubrovnik, 1821), writer and politician

- Konstantin Vojnović (Dubrovnik, 1832), politician, university professor and rector in the Kingdom of Dalmatia and Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia of the Habsburg Monarchy

- Ivo Vojnović (Dubrovnik, 1857), writer

- Tereza Kesovija (Dubrovnik, 1938), pop-classical-chanson singer

- Dubravka Tomšič Srebotnjak (Dubrovnik, 1940), pianist

- Milo Hrnić (Dubrovnik, 1950), pop singer

- Andro Knego (Dubrovnik, 1956), basketball player, Olympic and World champion

- Banu Alkan (Dubrovnik, 1958), female actor

- Dragan Andrić (Dubrovnik, 1962), water polo player, two-time Olympic champion

- Nikola Prkačin (Dubrovnik, 1975), basketball player

- Vlado Georgiev (Dubrovnik, 1976), pop singer, composer, and songwriter

- Frano Vićan (Dubrovnik, 1976), water polo player, Olympic, World and European champion

- Emir Spahić (Dubrovnik, 1980), football player

- Miho Bošković (Dubrovnik, 1983), water polo player, Olympic, World and European champion

- Nikša Dobud (Dubrovnik, 1985), water polo player, Olympic and World champion

- Lukša Andrić (Dubrovnik, 1985), basketball player

- Hrvoje Perić (Dubrovnik, 1985), basketball player

- Andro Bušlje (Dubrovnik, 1986), water polo player, Olympic, World and European champion

- Paulo Obradović (Dubrovnik, 1986), water polo player, Olympic and World champion

- Maro Joković (Dubrovnik, 1987), water polo player, Olympic, World and European champion

- Ante Tomić (Dubrovnik, 1987), basketball player

- Andrija Prlainović (Dubrovnik, 1987), water polo player, Olympic, World and European champion

- Sandro Sukno (Dubrovnik, 1990), water polo player, Olympic and World champion

- Mario Hezonja (Dubrovnik, 1995), basketball player

- Alen Halilović (Dubrovnik, 1996), football player

- Ana Konjuh (Dubrovnik, 1997), tennis player

Twin towns - sister cities

Dubrovnik is twinned with:[79]

In popular culture

The HBO series Game of Thrones used Dubrovnik as a filming location, representing the cities of King's Landing and Qarth.[80]

Parts of Star Wars: The Last Jedi were filmed in Dubrovnik in March 2016, in which Dubrovnik was used as the setting for the casino city of Canto Bight.[81][82]

Dubrovnik was one of the European sites used in the Bollywood movie Fan (2016), starring Shah Rukh Khan.

In early 2017, Robin Hood was filmed on locations in Dubrovnik.[83]

In Kander and Ebb's song "Ring Them Bells," the protagonist, Shirley Devore, goes to Dubrovnik to look for a husband and meets her neighbor from New York.[84]

The text-based video game Quarantine Circular[85] is set aboard a ship off the coast of Dubrovnik, and a few references to the city are made throughout the course of the game.

The Dubrovniks were an Australian Independent rock band formed in 1987. Often regarded as a 'Supergroup' due to the band members having played in various established bands such as Hoodoo Gurus, Beasts of Bourbon, and The Scientists. The band chose their name due to two members of the band Roddy Radalj (guitar vocals) and Boris Sujdovik (bass) being born in Dubrovnik.[86]

See also

References

- "Population by Age and Sex, by Settlements, 2011 Census: Dubrovnik". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2011. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. December 2012.

- "Dùbrōvnīk". Hrvatski jezični portal (in Croatian). Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- Oleh Havrylyshyn; Nora Srzentić (10 December 2014). Institutions Always 'Mattered': Explaining Prosperity in Mediaeval Ragusa (Dubrovnik). Palgrave Macmillan. p. 59. ISBN 9781137339782.

- "Bosna". Leksikon Marina Držića (in Croatian). Miroslav Krleža Institute of Lexicography and House of Marin Držić. 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- Whitley Stokes; Adalbert Bezzenberger (1894), "dubron", in August Fick (ed.), Vergleichendes Wörterbuch der indogermanischen Sprachen: Wortschatz der Keltischen Spracheinheit, 2 (4th ed.), Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 153–154

- Putanec, Valentin (June 1993). "Naziv Labusedum iz 11. st. za grad Dubrovnik" (PDF). Rasprave (in Croatian). Institute of Croatian Language and Linguistics. 19: 289–301. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- Andrew Archibald Paton (1862). "Chapter 9: Ragusa". Researches on the Danube and the Adriatic; or Contributions to the Modern History of Hungary and Transylvania, Dalmatia and Croatia, Servia and Bulgaria, Volume 1. London: Trübner and Co. p. 218. Retrieved 2016-02-10.

- ZBORNIK.indd (2009)

- "Picasa Web Albums – Dick ⁶– Dubrovnik, Cr..." 31 March 2010. Archived from the original on 31 March 2010.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- The Birth of Yugoslavia by Henry Baerlein

- Dubrovnik:A History by Robin Harris, chapter "Territorial expansion"

- Dubrovnik: A History, page 289, Robin Harris, Saqi Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0-86356-959-3

- Dubrovnik, 2nd: The Bradt City Guide, page 7, Piers Letcher, Robin McKelvie, Jenny McKelvie, Bradt Travel Guides, 2007. ISBN 978-1-84162-191-3

- Dubrovnik, page 25, Volume 581 of Variorum collected studies series, Bariša Krekić, Variorum, 1997. ISBN 978-0-86078-631-3

- The Late Medieval Balkans by John V. A. Fine and John Van Antwerp Fine, page 268

- Through Bosnia and the Herzegovina on Foot During the Insurrection by Sir Arthur Evans, pages 416 and 417

- Pitcher, Donald Edgar. An Historical Geography of the Ottoman Empire, Leiden: Brill, 1968, p. 70

- Radovinovic, Radovan, ed. (July 1999). The Croatian Adriatic Tourist Guide. Zagreb: Naprijed, Naklada. p. 354. ISBN 953-178-097-8.

- Husebye, Eystein Sverre. Earthquake Monitoring and Seismic Hazard Mitigation in Balkan Countries

- Dubrovnik and the American Revolution: Francesco Favi's Letters, Francesco Favi, ed. by Wayne S. Vucinich, Ragusan Press, 1977.

- Vojnović 2009, p. 187-189.

- Vojnović 2009, p. 240-241,247.

- Vojnović 2009, p. 147.

- Vojnović 2009, p. 150-154.

- Vojnović 2009, p. 191.

- Vojnović 2009, p. 172-173.

- Vojnović 2009, p. 194.

- Ćosić, Stjepan (2000). "Dubrovnik Under French Rule (1810–1814)" (PDF). Dubrovnik Annals (4): 103–142. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

- Vojnović 2009, p. 208-210.

- Vojnović 2009, p. 270-272.

- Vojnović 2009, p. 217-218.

- J. Fine (2010-02-05). When Ethnicity Didn't Matter. p. 155-156. ISBN 978-0472025602.

- Luigi Villari (1904). "The Republic of Ragusa : an episode of the Turkish conquest". J.M. Dent & Co.- London. p. 370.

- Marzio, Scaglioni (1996). "La presenza italiana in Dalmazia, 1866–1943". Tesi di Laurea (in Italian). Facoltà di Scienze politiche – Università degli studi di Milano. Archived from the original on 2010-09-14. Retrieved 2010-02-17.

- Trudna tożsamość: problemy narodowościowe i religijne w Europie Środkowo-Wschodniej w XIX i XX wieku. Instytut Europy Środkowo-Wschodnej. 1996. ISBN 978-83-85854-17-3.

- "Tramway in Dubrovnik". posta.hr. Croatian Post. Archived from the original on 2017-03-03. Retrieved 2017-03-02.

- "Dvije pobjede don Ive Prodana na izborima za Carevinsko vijeće u Beču".

- "6 Uninhabited and Mysterious Islands with Bizarre Pasts", The Daily Star, 28 October 2015.

- Politički zatvorenik "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-03-07. Retrieved 2016-02-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Retrieved 16 January 2012

- Dubrovnik Travel

- Dubrovnik Summer Festival

- The Informal Housing of Privatnici and the Question of Class Two Stories From The Post-Yugoslav Roadside, de Mišo Kapetanović et Ivana Katurić, Dans Revue d’études comparatives Est-Ouest 2015/4 (N° 46), pages 61 à 91

- Balkan Insight

- Srđa Pavlović. "Reckoning: The 1991 Siege of Dubrovnik and the Consequences of the "War for Peace"". Yorku.ca. York University. Retrieved 2017-03-02.

- Pearson, Joseph (2010). "Dubrovnik's Artistic Patrimony, and its Role in War Reporting (1991)". European History Quarterly. 40 (2): 197–216. doi:10.1177/0265691410358937.

- "Chronology for Serbs in Croatia". United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2004. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved January 5, 2011.

- Raymond Bonner (August 17, 1995). "Dubrovnik Finds Hint of Deja Vu in Serbian Artillery". The New York Times. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- "Pregled obnovljenih objekata". zod.hr (in Croatian). Institute for the Restoration of Dubrovnik. Archived from the original on May 8, 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- "Case information sheet: "DUBROVNIK" (IT-01-42) Pavle Strugar" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- "Dubrovnik Climate Normals" (PDF). Croatian Meteorological and Hydrological Service. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- "Monthly values and extremes: Values for Dubrovnik in 1961–2017 period" (in Croatian). Croatian Meteorological and Hydrological Service. Archived from the original on 11 January 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- "Dubrovnik, Croatia – Monthly weather forecast and Climate data". Weather Atlas. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- "DUBROVNIK news". archive.org. 21 October 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-10-21.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "50 kuna". hnb.hr. Croatian National Bank. 31 January 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- "Monuments (1 to 5)". Dubrovnik Online. Archived from the original on 2010-07-14. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- "TZ Seget – Dubrovnik". tz-seget.hr.

- "Eastern Europe: Where Is Eastern Europe?". aventalearning.com.

- Karen Tormé Olson; Sanja Bazulic Olson (2006). Frommer's Croatia. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 57–58. ISBN 0-7645-9898-8. Retrieved 27 October 2009.

- "Has Dubrovnik solved the problem of overcrowding from cruise ships?". The Telegraph.

- Oliver, Jeanne. "Dubrovnik Sights". Croatia Traveller. Archived from the original on 2010-02-27. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- "Sponza Palace". DubrovnikCity.com. Archived from the original on 2010-04-14. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- "The Rector's Palace". DubrovnikCity.com. Archived from the original on 2009-05-27. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- "The Rector's Palace". Dubrovnik Guide. Archived from the original on 2010-06-11. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- "Franciscan monastery". Dubrovnik Guide. Archived from the original on 2010-06-11. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- "Franciscan Friary, Dubrovnik". Sacred Destinations. Archived from the original on 2010-01-17. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- "Church of St. Blaise, Dubrovnik". Sacred Destinations. Archived from the original on 2010-01-20. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- "Monuments (16 to 20)". Dubrovnik Online. Archived from the original on 2010-07-14. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- "Dominican Friary, Dubrovnik". Sacred Destinations. Archived from the original on 2010-01-02. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- Oliver, Jeanne. "Dominican Monastery". Croatia Traveller. Archived from the original on 2010-01-04. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- "Monuments (21 To 22)". Dubrovnik Online. Archived from the original on 2009-07-25. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- Oliver, Jeanne. "Dubrovnik's Walls". Croatia Traveller. Archived from the original on 2010-01-04. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- "Encyclopedia, Dubrovnik". A&E Television Networks, History.com. Funk & Wagnalls' New Encyclopedia. World Almanac Education Group. Archived from the original on 2007-10-24. Retrieved 2010-02-14.

- "Population by Ethnicity, by Towns/Municipalities, 2011 Census: County of Dubrovnik-Neretva". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2011. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. December 2012.

- "Dubrovnik Airport: providing essential tourism support for a region. Croatia Airlines' 3rd base". centreforaviation.com. 22 August 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- "Transportation Rail". Dubrovnik Online. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- "Dubrovnik to Sarajevo 1965". Charlie Lewis. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- "Dubrovnik to Capljina in 1972". Jim Horsford. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- "The examination of the seabed started". China Road and Bridge Corporation. 23 August 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- "Gradovi prijatelji". dubrovnik.hr (in Croatian). Dubrovnik. Retrieved 2019-10-28.

- Dubrovnik in the spotlight Archived 2013-03-11 at the Wayback Machine, jaywaytravel.com.

- "[VIDEO] Star Wars Episode VIII Starts Shooting in Dubrovnik this Week". Croatia Week. 8 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- Milekic, Sven (15 February 2016). "Star Wars Adds Shine to Croatian 'Pearl' Dubrovnik". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- "Take a look around the set of the new Robin Hood movie being filmed in Dubrovnik". Nottingham Post. 29 December 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- "Ring Them Bells Lyrics". MetroLyrics. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- Yin-Poole, Wesley (2018-05-22). "Mike Bithell follows up Subsurface Circular with Quarantine Circular". Eurogamer. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- McFarlane, Ian (1999). "Whammo Homepage". Encyclopedia of Australian Rock and Pop. St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86508-072-1. Archived from the original on 5 April 2004. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

Bibliography

- Peterjon Cresswell; Ismay Atkins & Lily Dunn (2006). Time Out Croatia (First ed.). London, Berkeley & Toronto: Time Out Group Ltd. & Ebury Publishing, Random House Ltd. ISBN 978-1-904978-70-1. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- Robin Harris (2003). Dubrovnik, A History. London: Saqi Books. ISBN 0-86356-332-5.

- Adriana Kremenjaš-Daničić, ed. (2006). Roland's European Paths. Dubrovnik: Europski dom Dubrovnik. ISBN 953-95338-0-5.

- Marko Kovac (February 4, 2003). "Dubrovnik's Heritage Under Threat". BBC News Online.

- Frank McDonald (July 18, 2008). "The 'Pearl' loses its lustre". The Irish Times. Retrieved March 2, 2017.

- Joshua Wright (June 7, 2004). "Will greed tarnish Croatia's gem?". The New York Times. Retrieved March 2, 2017.

- Vojnović, Lujo (2009). Pad Dubrovnika (1797.-1806.). Fortuna. ISBN 978-953-95981-9-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- "Ragusa", Bradshaw's Hand-Book to the Turkish Empire, 1: Turkey in Europe, London: W.J. Adams, c. 1872

- David Kay (1880), "Principal Towns: Ragusa", Austria-Hungary, Foreign Countries and British Colonies, London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington, hdl:2027/mdp.39015030647005

- R. Lambert Playfair (1892). "Ragusa". Handbook to the Mediterranean (3rd ed.). London: J. Murray.

- "Ragusa". Austria-Hungary, Including Dalmatia and Bosnia. Leipzig: Karl Baedeker. 1905. OCLC 344268.

- F. K. Hutchinson (1909). "Ragusa". Motoring in the Balkans. Chicago: McClurg & Co. OCLC 8647011. OL 13515412M.

- Trudy Ring, ed. (1996). "Dubrovnik". Southern Europe. International Dictionary of Historic Places. 3. Fitzroy Dearborn. OCLC 31045650.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dubrovnik. |

- Official website

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Old City of Dubrovnik

- Encyclopædia Britannica.com: Dubrovnik

- Youtube.com: Dubrovnik — digital video reconstruction — by GRAIL at Washington University.