Pelješac Bridge

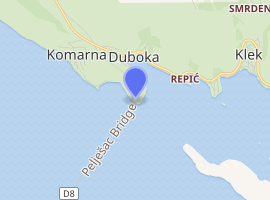

The Pelješac Bridge (Croatian: Pelješki most, pronounced [pěʎeʃkiː môːst][1][2]) is a bridge currently under construction in Croatia. The purpose of the bridge is to achieve the territorial continuity of the Republic of Croatia by connecting the southern exclave comprising the bulk of Dubrovnik-Neretva County with the remainder of the Croatian mainland. The bridge will span the Pelješac Channel between Komarna on the northern mainland and the peninsula of Pelješac, thereby passing entirely through Croatian territory and circumventing any border crossings with neighbouring Bosnia and Herzegovina at Neum.

Pelješac Bridge | |

|---|---|

Construction site in June 2020 | |

| Coordinates | 42°56′23″N 17°32′38″E |

| Carries | 4-lane wide expressway |

| Crosses | Neretva Channel / Bay of Mali Ston |

| Locale | South-east Croatia |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Cable-stayed bridge |

| Total length | 2,404 metres (7,887 ft) |

| Width | 23.6 metres (77 ft) |

| Longest span | 5 x 285 metres (935 ft) |

| Clearance below | 55 metres (180 ft) |

| History | |

| Constructed by | China Road and Bridge Corporation |

| Construction start | July 30, 2018 |

| Construction end | 2022 (planned) |

| |

Construction commenced 30 July 2018, and is scheduled to be completed by the end of 2022.[3]

Characteristics

According to the construction plan from 2007, the Pelješac Bridge was planned to be a 2,404-metre (7,887 ft) long, 55-metre (180 ft) high beam and cable-stayed bridge, with a main span of 568 metres (1,864 ft). The plan was changed later.

According to the current plan, the bridge will be a multi-span cable-stayed bridge with a total length of 2,404-metre (7,887 ft). It will comprise 13 spans, while seven will be cable-stayed - five central 285-metre (935 ft) spans and two outer 203.5-metre (668 ft) spans. Two pylons around the 200-metre (660 ft) x 55-metre (180 ft) navigation channel will be 98-metre (322 ft) above sea level and 222-metre (728 ft) above the seabed.[4][5]

Beside the construction of the bridge, access roads at both sides of the bridge require construction, including 2 tunnels on Pelješac (one 2,170 metres (7,120 ft) and other 450 metres (1,480 ft) long) as well as two smaller bridges on Pelješac, (one 500 metres (1,600 ft) and another 50 metres (160 ft) long). The bridge cannot form part of the A1 motorway, currently connecting Zagreb and Ploče, because it is not planned to include the requisite number of lanes to support it. The road from Ploče through the bridge towards Ston and further south to Dubrovnik is planned to be a 4-lane expressway.

History

Because the Croatian mainland is intersected by a small strip of the coast around the town of Neum which is part of Bosnia and Herzegovina, forming Bosnia and Herzegovina's only outlet to the sea, the physical connection of the southernmost part of Dalmatia with the rest of Croatia is limited to Croatian territorial waters.

In 1996, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia signed the Neum Agreement in which Croatia was granted unobstructed passage through Neum,[6] but the agreement was never ratified. All traffic passing through the Neum corridor has to undergo border checks on goods and persons. Therefore, people travelling from the Dubrovnik exclave to mainland Croatia must currently pass through two border checks in the space of 9 kilometers (6 mi). Should Croatia join the Schengen Area in future (which it is in theory bound to do in accordance with the conditions of its accession to the European Union), checks would be considerably more stringent and time-consuming, as the Schengen Borders Code requires checks not only when entering the Schengen area, but also when exiting it. Thus, someone travelling from Dubrovnik to mainland Croatia would undergo three distinct border checks: a Croatian (Schengen) exit check, a Bosnia-Herzegovina entry check, and a Croatian (Schengen) entry check. While Bosnia-Herzegovina's border checks for European countries passport holders at tourist locations are usually quick visual checks to verify that the passport photograph matches the individual presenting the passport and that the passport has not expired, Schengen checks now involve scanning all passports (even those of citizens with a right to unrestricted EU-wide free movement) against various databases, which can take up to 30 seconds per individual. Thus, as an example, a car containing four people could be stopped for two minutes at each Croatian border. In the summer tourist season, such a prospect would lead to unsustainable border delays and require an urgent solution, such as a bridge bypassing Neum and remaining in Croatia.

The construction of the bridge was publicly proposed in 1997 by Ivan Šprlje, the Prefect of the Dubrovnik-Neretva County and member of the Social Democratic Party of Croatia (SDP). Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) initially rejected the idea, but in 1998 it gained support of their MP Luka Bebić. In 2000, the bridge was added to the spatial plan of the County and the first construction plans were drawn up.[7]

The construction works on the Pelješac project officially commenced in November 2005 with a grand opening led by then Prime Minister, Ivo Sanader.[7] Despite the price of the bridge project rising significantly compared to the initial estimate, the government persisted with the idea of a bridge. The initial design was changed to reflect the concerns of Bosnia and Herzegovina to the first plans. The two sides agreed on the construction of the bridge in early December 2006.[8]

In May 2007, the Croatian minister of infrastructure Božidar Kalmeta said that preparations for the construction of the bridge were going according to plan and that an initial tender was under preparation. Kalmeta added that the question of when the construction works would begin depended on whether a constructor would be selected in the first round.[9] On June 11, 2007, Hrvatske ceste announced a public tender for the construction of the bridge. On August 28, the list of bidders was released: Konstruktor, Viadukt and Hidroelektra (from Croatia); Dywidag (Germany), Strabag (Austria), Cimolai (Italy), Eiffel (France); and Alpine Bau (from Salzburg, Austria)

Kalmeta confirmed construction works were to start in Autumn 2007. The contractor was to be obliged to complete the project in four years. Construction costs were estimated at HRK 1.9 billion, nearly 260 million euros.[10] It would be financed by Hrvatske ceste and by loans by European investment banks.[10]

In June 2007, after the tender was published, the media reported renewed opposition from the State Border Commission in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Bosnia and Herzegovina declared that it would sue Croatia if it started building the bridge unilaterally.[11]

On September 14, 2007, the Ministry of Construction announced that the Konstruktor/Viadukt/Hidroelektra consortium had won the contest and that it would sign a contract for 1.94 billion kuna, roughly 265 million euros at the time. Construction works on the northern and southern termini commenced on October 24, 2007,[12] with sea works starting in the autumn of 2008.

In July 2009, the Croatian Government under Jadranka Kosor announced that, as part of the effort to reduce expenses during the economic crisis, the construction of the Pelješac Bridge was to proceed under a much slower timetable than originally planned. In November 2009 Kalmeta mentioned 2015 as the year of completion. The 2010 budget and road-building programme indicated that by the end of 2012, only 433.5 million kuna or 60 million euros would be invested in the bridge, which is less than a quarter of the total.[13]

After the Croatian parliamentary election, 2011, the new SDP-led government terminated the existing construction contract worth 1.94 billion kuna (c. 259 million euro) for lack of funds in May 2012.[14][15][16][17] At the same time, plans were made to use the bridge construction sites as new ferry docking sites.[18][19] There was also discussion regarding how the cost and speed of the ferry solution would compare to that of the cancelled bridge, with the Minister of Maritime Affairs, Transport and Infrastructure claiming the ferrying would be less expensive and reasonably fast, as well as complete by 1 July 2013, which is when Croatia joined the European Union and when the new border regime could have become a problem.[20][21]

In 2012 the European Union granted Croatia a sum of 200.000 euros for a pre-feasibility study of the construction of the Pelješac Bridge. The study would examine not only the projected bridge, but also the solution of a closed road corridor across the hinterland of Neum. "The strategic aim of the Government is to effectively connect the territory of Croatia, which is also a goal of the EU, because the Croatian territory is to become a territory of the Union. This project should not be politicized, but rather we should see which action is most cost-effective", foreign minister Vesna Pusić claimed. She also emphasized that the ratification of the Tuđman-Izetbegović treaty of 1996 (Neum Agreement) was not a condition to receive European funds for the construction of the bridge, but it would be no harm if it did happen.[22]

The feasibility study prepared by Croatia to analyse the possible alternatives concluded that building a bridge would be the most favourable option as it scored highest in the multi-criteria (safety, impact on traffic, environmental impact) and cost-benefit analysis, compared to the other options – a highway corridor, a ferry connection or the construction of tunnels. The project was prepared in consultation with the authorities of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The necessity to preserve Croatia's natural heritage was an essential criteria taken into consideration at all phases of the project's preparation.[23]

The European Commission also had the project assessed before adoption independent experts in the framework of the Joint Assistance to Support Projects in European Regions (JASPERS)[24] as regards its feasibility and economic viability.[23]

A French study suggested in December 2013 that the bridge is the most feasible solution, and Croatian Minister of Traffic stated that the construction of the bridge would start in 2015.[25] In July 2015 Croatia's government said that construction was likely to start in spring 2016.[26]

By 2016, the Croatian government was saying construction would go ahead with or without EU funds.[27] Construction dates were further delayed by a formal complaint about tender documents. [28]

The European Commission announced on 7 June 2017 that €357 million from EU Cohesion policy funds will be made available for the bridge and the supporting infrastructure (tunnels, bypasses, viaducts and access roads), with completion scheduled for 2022. The EU contribution would amount to 85% of the total construction costs, aiming at benefiting tourism, trade, and territorial cohesion.[23]

Despite protests from Bosnian political actors, Croatia's regional development minister Gabrijela Zalac[29] as well as Croatian PM Andrej Plenković[30] confirmed that the construction of the bridge would continue.

On September 15, 2017, it was announced that China Road and Bridge Corporation, Austrian Strabag and Italian-Turkish consortium Astaldi - Içtas applied for a bridge construction tender. The Austrians offered the cost of 2,622 billion kuna, the Italo-Turkish offer was 2,551 billion kuna, while the Chinese offer was 2,08 billion kuna.[31] On January 15, 2018 Hrvatske ceste made a formal decision according to which China Road and Bridge Corporation won the tender. Except for the lowest price, CRBC also offered to complete the project six months faster than required.[32]

Construction had started by mid 2019,[33] with the construction of the bridge pillars in October.[34][35]

Controversial aspects

Environmental protection

The idea that a large bridge should connect Pelješac with the mainland has caused concern among the ecological activists in Croatia, who opposed it because of a potential damage to the sea life in the bay of Mali Ston, as well as the mariculture.[36] These risks and concerns were explicitly addressed by the constructors in the preliminary studies.[37]

In October 2015 the Croatian Ministry of Environment and Nature Protection (now the Ministry of Environment and Energy) issued a Decision, confirming that a cross-border consultation was carried out concerning the impact of the project on the environment of Bosnia and Herzegovina according to Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment in a Transboundary Context (Espoo Convention). Bosnia and Herzegovina did not submit its observations nor requested an extension of the consultation's timeframe.

Cost-benefit analysis

The idea is also opposed for various economic reasons - whether such a bridge is really necessary as opposed to making a different deal with Bosnia and Herzegovina,[38] whether it is too expensive if built according to ecological demands, or whether it is best replaced with an undersea tunnel.[39]

The idea of construction of an immersed tube instead as a more cost-effective design, not impeding access to Neum, was ridiculed and never accepted by the Croatian authorities.[7][40][41]

Dnevnik Nova TV has also showed that a highly-surveillanced highway corridor with high walls through Bosnia-Herzegovina was another possibility.[42]

In the process of accession of Croatia to the European Union, the Croatian Government had claimed that a bridge would be a "prerequisite" for Croatia to enter the Schengen Area. The European Commission nevertheless stated in 2010 that this is only one of several options to handle the issue.[43]

International law and access of Bosnia and Herzegovina to the high seas

The construction of the bridge has also been opposed by various political actors in Bosnia and Herzegovina, mostly Bosniak, as it would, according to them, complicate its access to international waters.[44] Bosnian authorities initially opposed the building of the bridge, originally planned to be only 35 meters (115 feet) high, because it would have made it impossible for large ships to enter the harbor of Neum.[45] Although Neum harbor is not currently fit for commercial traffic, and most of the trade to and from Bosnia and Herzegovina goes through the Croatian port of Ploče, the Bosnian government declared that a new one might be built in the future, and that the construction of the bridge would compromise this ambition.

In August 2017 a group of unnamed Bosnian MPs wrote a letter to the EU foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini of Italy and to the international representative in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Valentin Inzko of Austria, claiming that Croatia is in violation of the United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea and is "cutting off without permission" their country from international waters through the Pelješac bridge project, calling upon Croatia "to stop attacking the sovereignty of Bosnia and Herzegovina as a maritime state and stop all activities on building an illegal and politically violent bridge project at the Komarna-Pelješac peninsula location." The Bosnian MPs noted that Bosnia and Herzegovina has never given formal consent, by the Council of Ministers nor by the Presidency, to the bridge project and its financing with EU funds.[46][47]

Croatia claims that the bridge is located exclusively within Croatian territory and Croatian territorial waters and that it is thus entitled under the international law of the sea to construct the bridge without requiring any consent from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Croatia also expressed commitment to fully respect the international rights enjoyed by other countries in the Pelješac peninsula, including the right of innocent passage enjoyed by all countries under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, and the right of Bosnia and Herzegovina to have unrestricted access to the high seas. Croatia also recalled that the foreseen height of the bridge (55 m, 180 ft) will allow the totality of the current Bosnian shipping to use the existing navigational route to transit under the bridge, and that in case any ship taller than 55 meters (180 ft) would need to call on a port in Bosnia and Herzegovina, it could dock instead at the Croatian Ploče port, in line with the 1995 Free Transit agreement.

According to veteran Bosnian politician and MP Halid Genjac, “the claims that Croatia is building a bridge on its territory are incorrect because the sea waters beneath the Peljesac bridge are not and cannot be Croatian or internal waters, but international waters stretching from the territorial waters of Bosnia and Herzegovina to the open sea.”[29]

Link with border demarcation treaty ratification

Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia agreed on a border demarcation treaty in 1999. The treaty was signed by the two former presidents, Alija Izetbegović and Franjo Tuđman, but it was never ratified by the respective parliaments so, therefore, it had never entered into force. The agreement foresees a definition of the two countries' territory, in the area of the Pelješac peninsula which is slightly different from what is shown on maps, since Croatia agreed to recognise the sovereignty of Bosnia and Herzegovina over two small rock islands (Mali Školj and Veliki Školj) and the tip of the peninsula of Klek near Neum.[29]

On 17 October 2007 the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina adopted an official position stating that "Bosnia and Herzegovina opposes the construction of the [Pelješac] bridge until the issues related to the determination of the sea borderline between the two countries are resolved" and asking Croatia not to undertake any unilateral actions concerning the construction of the bridge. Bosnian MP Halid Genjac has stated that such official position has never been reverted and is thus still in force, while no official Bosnian body has given its express consent to the construction of the bridge. He argued that “the claims that Croatia is building a bridge on its territory are incorrect because the sea waters beneath the Peljesac bridge are not and cannot be Croatian or internal waters, but international waters stretching from the territorial waters of Bosnia and Herzegovina to the open sea,” Genjac argued.[29][48]

The Bosniak member of the BiH Presidency, Bakir Izetbegović, stated that he believed that Croatia should not proceed with the building of the bridge before the maritime border demarcation is agreed, based on the 2007 position of the BiH Presidency, and that the agreement for the use of the port of Ploče has not been ratified yet either.[49]

Croat member of the BiH Presidency, Dragan Čović continuously supports the construction of the bridge and has stated that "problematizing the construction of Pelješac bridge is not the official position of BiH. The official position of recent years has been in the sense of encouraging Croatia to continue with such an infrastructure project that is of great importance for BiH as well. In this case, it's about one party's (SDA) position and of a couple of individuals in that party. Croatia complied with all the set conditions."[50]

Serb member of the BiH Presidency Mladen Ivanić stated that he supported the construction and that it was necessary to ensure that the maritime regime was such that ships could freely come to Neum.[51][52]

President of Republika Srpska Milorad Dodik stated in August 2017 that Croatia had the right to build the Pelješac bridge, adding that Bosniak parties were unnecessarily creating problems.[53]

References

- "pèlješkī". Hrvatski jezični portal (in Croatian). Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- "mȏst". Hrvatski jezični portal (in Croatian). Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Windisch, Elke (2 August 2018). "Kroatien will "endlich eins" werden" [Croatia finally wants to be one] (in German). Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- "Pelješac Bridge (Komarna/Brijesta, 2022)". Structurae. Retrieved 2020-06-02.

- "Pelješac Bridge - Pipenbahe Consulting, biridge design, viaduct design, wind analysis, - Pipenbaher Consulting Engineers". pipenbaher-consulting.com. Retrieved 2020-06-02.

- "Neum Agreement, May 1996" (PDF). Technical annex on a proposed loan to the Republic of Croatia for an emergency transport and mine clearing project. World Bank. October 15, 1996. pp. 45–47. Retrieved 2010-12-27.

- "Nikad ispričana priča o Pelješkom mostu: Tri puta živio, tri puta umro, tri vlade mučio je gradnjom. Opet je oživio". Jutarnji list (in Croatian). 2011-08-24. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- "BiH, Croatia seek agreement on proposed bridge". Southeast European Times. 2007-04-11. Retrieved 2010-05-14.

- "Kalmeta and Ljubic on Croatia's plan to build Peljesac bridge". Croatian Ministry of Sea, Tourism, Transport and Development. Archived from the original on 2007-06-12.

- Slobodna Dalmacija (2007-06-12). "Kalmeta: Bridge to Peljesac in 2011". Limun.hr. Retrieved 2010-05-14.

- "Bosnia vexed by Croatian bridge". BBC. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2010-05-14.

- "Construction on Pelješac Bridge starts, Brijest". T-portal.hr. 2007-10-24.

- "Kapitalni državni projekt čekat će izlazak iz recesije - Konzerviranje radova - Pelješki most 'tanak' za 1,6 milijarda kuna". Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian). December 18, 2009.

- "Hajdaš Dončić: Nemamo 4 milijarde kuna za Pelješki most". Dnevnik.hr (in Croatian). Nova TV (Croatia). 2012-05-09. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- "Pelješki most otišao u povijest. Hajdaš Dončić: Izvođačima će se platiti za već obavljeni posao, ali ne i naknadu za izgubljenu dobit". Jutarnji list (in Croatian). 2012-05-17. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- "Čačić o odustajanju od Pelješkog mosta: To bi bilo kao da ložite peć novčanicama od 100 eura". Novi list (in Croatian). 2012-04-20. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- "Pelješki most otišao u povijest. Milanović: Taj most nije besmislica, ali njegova izgradnja nije dovoljno ozbiljno isplanirana" [Pelješac Bridge is history. Milanović: That bridge is not a nonsense, but its construction was not sufficiently seriously planned]. Večernji list (in Croatian). 17 May 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- "Gradilište Pelješkog mosta pretvara se u trajektnu luku za kamione?". Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian). 2012-05-10. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

- ""Plava obilaznica" Neuma: Umjesto mosta i koridora, Hrvatska gradi dva trajekta?" (in Croatian). Index.hr. 2012-06-04. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

- Josip Bohutinski (4 June 2012). "Trajekti će biti skuplji i od pelješkog mosta" [Ferries to cost more than the Pelješac Bridge]. Večernji list (in Croatian). Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- "Nova trajektna linija kopno - Pelješac" (in Croatian). Croatian Radiotelevision. 2012-06-05. Retrieved 2012-06-09.

- Piše: M.L. ponedjeljak, 10.9.2012. 20:56 (2012-10-09). "Iz Europske unije stiže novac za Pelješki most: Hrvatskoj za predstudiju odobreno 200.000 eura - Vijesti". Index.hr. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- "Commission approves EU financing of the Pelješac bridge in Croatia". European Commission. 7 June 2017. Retrieved 2017-08-04.

- "JASPERS: Joint Assistance to Support Projects in European Regions". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- "Peljesac bridge is best solution to connect the south of Croatia". Croatian Times. 11 December 2013. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013.

- "Croatia: Delayed bridge bypassing Bosnia goes ahead". BBC News. BBC Monitoring. 15 July 2015. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- Matijaca, Danni (14 Apr 2016). "Construction of Pelješac Bridge Starting Soon With or Without EU Funds". Total Croatia News.

- Pavlic, Vedran (10 Oct 2016). "Deadlines for Pelješac Bridge Delayed Once Again". Total Croatia News.

- "Croatia Rejects Bosnian 'Threats' Over Peljesac Bridge". 2017-08-07. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- "Plenković: Pelješac Bridge Project Will Continue". Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- "FOTO: Tri ponude za Pelješki most, Kinezi najjeftiniji". Retrieved 2018-01-16.

- "TKO SU KINEZI KOJI BI TREBALI SAGRADITI PELJEŠKI MOST S moćnim državnim konglomeratom dvije hrvatske tvrtke već su ugovorile suradnju". jutarnji.hr. Retrieved 2018-01-16.

- Parrock, Jack (2019-07-30). "Much-delayed €420m bridge to connect Croatia back on track". euronews. Retrieved 2019-11-14.

- "PHOTOS: Peljesac Bridge progress update". Croatia Week. Retrieved 2019-11-14.

- "PHOTOS: Peljesac Bridge progressing at speed". Retrieved 2020-03-18.

- Eduard Šoštarić (2007-03-13). "Natječaj za most Jarun je namješten" [Jarun Bridge tender is rigged]. Nacional (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 2010-05-14.

- Institut IGH. "The Summary Study on the Pelješac Bridge" (PDF). Croatian Ministry of Nature Preservation.

Iz, u SUO, opisanih hidrogeoloških značajki područja istraživanja uočljivo je da se s pristupnih cesta, a i s Mosta kopno - Pelješac ne smije dopustiti direktan upoj voda u okolni teren bez prethodnog pročišćavanja.

- "The Government needs to issue a public tender for the Peljesac Bridge". Nacional. 2005-11-21. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 2010-05-14.

- "The Peljesac Bridge would be much better off as a Tunnel". KorčulaInfo.com. 2006-12-12. Archived from the original on 2010-04-19. Retrieved 2010-05-14.

According to article published in Slobodna Dalmacija [...] prof. dr. sc. Jure Radnić, the head of Bridge and Concrete Department of Faculty of Civil Engineering from Split, Croatia [...] told them that much better and cheaper way to solve the problem of connecting Croatian territories, would be a TUNNEL (!)

- "Gospođo Kosor, zašto gradite sedam puta skuplje?" [Mrs. Kosor, why build seven times more costly?] (in Croatian). limun.hr. 11 September 2009. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- "Umjesto Pelješkog mosta - podvodni tunel?" [Undersea tunnel instead of Pelješac Bridge?] (in Croatian). index.hr. 29 July 2009. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- Mislav Bago/T.V. (2015-06-16). "Animacija: Ovako bi mogla izgledati nova verzija Pelješkog mosta!". Dnevnik.hr. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- "EK objašnjava: Pelješki most nije uvjet za uspostavu Schengena". Večernji list (in Croatian). 2010-10-23. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- "Sarajevski ultimatum: Bosna do Italije". Globus (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- "BiH protiv nižeg Pelješkog mosta" (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- "Akcija bh. parlamentaraca: Hrvatska ne smije graditi Pelješki most". 2 August 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- "Bh. parlamentarci spremaju pismo EU: Lažirana saglasnost BiH za gradnju Pelješkog mosta". Novinska agencija Patria. 2017-08-03. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- "Bosnia Determined to Stop Pelješac Bridge Construction". Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- "Bosnian Leader: "Croatia Cannot Build Pelješac Bridge"". Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- "Čović u Temi dana: Problematiziranje gradnje Pelješkog mosta nije službeno stajalište BiH". Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- "Mladen Ivanić: Granicu sa Srbijom riješiti po principu "metar za metar"".

- "Mladen Ivanić: Milorad Dodik izmišlja, sam sebe ubijedi u stvari koje ne stoje". Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- "DODIK POKLOPIO IZETBEGOVIĆA 'Hrvatska ima pravo graditi Pelješki most na svome teritoriju. Bošnjačke strane nepotrebno stvaraju probleme'". Retrieved 26 March 2018.

Further reading

- Damir Arnaut "Adriatic Blues: Delimiting the Former Yugoslavia's Final Frontier". The Limits of Maritime Jurisdiction. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. 2013. pp. 167–171. ISBN 9789004262591.

External links

- Pelješac Bridge at Structurae. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- Computer visualization of the Pelješac Bridge

- Details of the construction of the Pelješac Bridge

- Pelješac Bridge Viadukt's billboard

- "Detailed map of the location of the bridge (North)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-01-14. (286 KB).

- "Detailed map of the location of the bridge (South)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-11-24. (352 KB).

- "Study on the motorway between Ploče, Dubrovnik and border crossing with Montenegro at Debeli Brijeg, including the Pelješac bridge" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-05-06. (726 KB) - In Croatian with short English summary .

- Bosnia forbids passage of Dubrovnik motorway through its territory