Makarska

Makarska (Serbo-Croatian pronunciation: [mâkarskaː]; Italian: Macarsca, pronounced [ma'karska]; German: Macharscha) is a small city on the Adriatic coastline of Croatia, about 60 km (37 mi) southeast of Split and 140 km (87 mi) northwest of Dubrovnik. It has a population of 13,834 residents.[1] Administratively Makarska has the status of a city and it is part of the Split-Dalmatia County.

Makarska | |

|---|---|

| Grad Makarska City of Makarska | |

Makarska | |

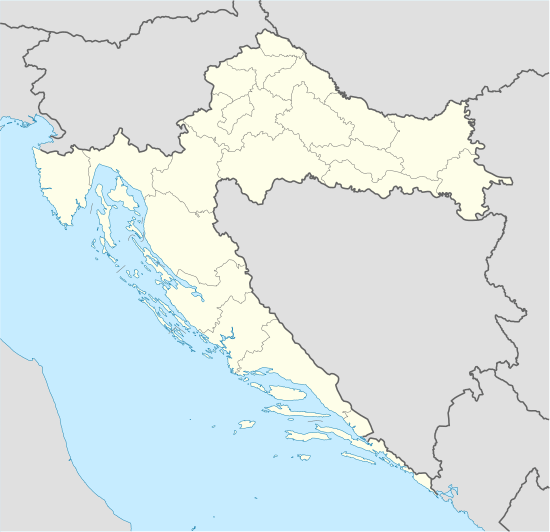

Makarska Location of Makarska in Croatia | |

| Coordinates: 43°18′N 17°02′E | |

| Country | |

| County | |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Jure Brkan (HDZ) |

| • President of City Council | Marko Ožić-Bebek (HDZ) |

| Area | |

| • City | 40 (Makarska and Veliko Brdo) km2 (15 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 28 (City of Makarska) km2 (11 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • City | 13,834 |

| • Density | 360/km2 (920/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | HR-21 300 |

| Area code(s) | +385 21 |

| Vehicle registration | MA |

| Website | www |

Makarska is a tourist centre, located on a horseshoe shaped bay between the Biokovo mountains and the Adriatic Sea. The city is noted for its palm-fringed promenade, where cafes, bars and boutiques overlook the harbour. Adjacent to the beach are several large capacity hotels as well as a camping ground.

The center of Makarska is an old town with narrow stone-paved streets, a main church square where there is a flower and fruit market, and a Franciscan monastery that houses a sea shell collection featuring a giant clam shell.

Makarska is the center of the Makarska Riviera, a popular tourist destination under the Biokovo mountain. It stretches for 60 km (37 mi) between the towns of Brela and Gradac.

Its former cathedral of Saint Mark was the see of the former Roman Catholic Diocese of Makarska which was merged in 1828 into the Diocese of Split-Makarska.

History

Pre-history

Near present-day Makarska, there was a settlement as early as the middle of the 2nd millennium BC. It is thought that it was a point used by the Cretans on their way up to the Adriatic (the so-called "amber road"). However it was only one of the ports with links with the wider Mediterranean, as shown by a copper tablet with Cretan and Egyptian systems of measurement.

A similar tablet was found in the Egyptian pyramids. In the Illyrian era this region was part of the broader alliance of tribes, led by the Ardaeans, founded in the third century BC in the Cetina area (Omiš) down to the River Vjosë in present-day Albania.[2]

The Roman era

Although the Romans became rulers of the Adriatic by defeating the Ardiaei in 228, it took them two centuries to confirm their rule. The Romans sent their veteran soldiers to settle in Makarska. After the division of the Empire in 395, this part of the Adriatic became part of the Eastern Roman Empire and many people fled to Muccurum from the new wave of invaders. The city appears in the Tabula Peutingeriana as the port of Inaronia, but is mentioned as Muccurum, a larger settlement that grew up in the most inaccessible part of Biokovo mountain, probably at the very edge of the Roman civilisation. It appears as Macrum on the acts of the Salonan Synod of 4 May 533 AD held in Salona (533),[2][3] when also the town's diocese was created.

Early Middle Ages

During the Migration Period, in 548, Muccurum was destroyed by the army of the Ostrogoth king Totila. The byzantine Emperor expelled the Eastern Goths (Ostrogoths).

In the 7th century the region between the Cetina and Neretva was occupied by the Narentines, with Mokro, located in today's Makarska, as its administrative centre. The doge of Venice Pietro I Candiano, whose Venetian fleet aimed to punish the piratesque activities of the city's vessels, was defeated here on September 18, 877[2] and had to pay tribute to the Narentines for the free passage of its ships on the Adriatic.

Late Middle Ages

The principality was annexed to the Kingdom of Croatia in the 12th century, and was conquered by the Republic of Venice a century later. Making use of the rivalry between the Croatian leaders and their power struggles (1324–1326), the Bosnian Ban Stjepan II Kotromanić annexed the Makarska coastal area. There were many changes of rulers here: from the Croatian and Bosnian feudal lords, to those from Zahumlje (later Herzegovina).

In the eventful 15th century the Ottomans conquered the Balkans. In order to protect his territory from the Turks, Duke Stjepan Vukčić Kosača handed the region to the Venetians in 1452.[4] The Makarska coastal area fell to the Turks in 1499.[5]

Under the Turks

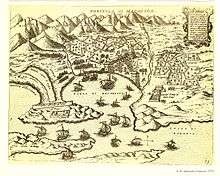

Under the Ottoman rule, the city was surrounded with walls that had three towers. The name Makarska was cited for the first time in a 1502 document telling how nuns from Makarska were permitted to repair their church.[2] The Turks had links with all parts of the Adriatic via Makarska and they therefore paid a great deal of attention to the maintenance of the port. In 1568 they built a fortress as defence against the Venetians. During Turkish rule the seat of the administrative and judicial authority was in Foča, Mostar, for a short time in Makarska itself and finally in Gabela on the River Neretva.

During the Candian War between Venice and the Turks (1645–1669) the desire among the people of the area to be free of the Turks intensified, and in 1646 Venice recaptured the coastline. A period of dual leadership, marked with armed conflicts, destruction and reprisals, lasted until 1684, until the danger of the Turks ended in 1699.[2][6]

Once more under the Venetians

In 1695 Makarska became the seat of a bishopric and commercial activity came to life, but it was a neglected area and little attention was given to the education of its inhabitants. At the time when the people were fighting against the Turks, and Venice paid more attention to the people's demands. According to Alberto Fortis in his travel chronicles (18th century), Makarska was the only town in the coastal area, and the only Dalmatian town where there were absolutely no historical remains.

After the fall of the Venetian Republic, it was given to the Austrians by the Treaty of Campo Formio (1797).

From 1797 to 1813

With the fall of Venice, the Austrian army entered Makarska and remained there until Napoleon took the upper hand. The French arrived in Makarska on 8 March 1806 and remained until 1813. This was an age of prosperity, cultural, social and economic development. Under French rule all the people were equal, and education laws written, for the first time in many centuries, in the Croatian language were passed. Schools were opened. Makarska was at this time a small town with about 1580 inhabitants.[2]

Under the Austrians (1813–1918)

As in Dalmatia as a whole, the Austrian authorities imposed a policy of Italianization, and the official language was Italian. The Makarska representatives in the Dalmatian assembly in Zadar and the Imperial Council in Vienna demanded the introduction of the Croatian language for use in public life, but the authorities steadfastly opposed the idea. One of the leaders of the National (pro-Croatian) Party was Mihovil Pavlinović of Podgora. Makarska was one of the first communities to introduce the Croatian language (1865).

In the second half of the 19th century Makarska experienced a great boom and in 1900 it had about 1800 inhabitants. It became a trading point for agricultural products, not only from the coastal area, but also from the hinterland (Bosnia and Herzegovina) and had shipping links with Trieste, Rijeka and Split.

The Congress of Vienna assigned Makarska to Austria-Hungary, under which it remained until 1918.

The 20th century

In the early 20th century agriculture, trade and fishing remained the mainstay of economy. In 1914, the first hotel was built, beginning the tourism tradition in the area. During World War II, Makarska was part of the Independent State of Croatia. It was a port for the nation's navy and served as the headquarters of the Central Adriatic Naval Command, until it was moved to Split.[7]

After the war, during communist Yugoslavia, Makarska experienced a period of growth, and the population tripled. All the natural advantages of the region were used to create in Makarska one of the best known tourist areas on the Croatian Adriatic.

Main sights

- St. Mark's Cathedral (17th century), in the Main Square.

- Statue of the friar Andrija Kačić Miošić by the famous Croatian sculptor Ivan Rendić.

- St. Philip's Church (18th century).

- St. Peter's church (13th century), situated on the Sv. Petar peninsula, rebuilt in 1993.

- The Franciscan monastery (16th century). It houses a library with numerous books and rare incunabulas and a famous, world known collection of shells from all over the world, collected in a Malacological Museum from 1963.

- Napoleon monument, erected in the honour of the French Marshal Marmont in 1808.

- The Baroque Ivanišević Palace.

- Villa Tonolli, which is home to the Town Museum.

Climate and vegetation

Makarska experiences a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification: Csa). Winters are warm and wet, while summers are hot and dry.

Makarska is one of the warmest cities in Croatia.

Vegetation is the evergreen Mediterranean type, and subtropical flora (palm-trees, agaves, cacti) grow in the city and its surroundings.

Notable natives/residents

- Giuseppe Addobbati (1909–1986) - Italian film actor

- Jure Bilić (1922–2006) - Yugoslav and Croatian politician

- Alen Bokšić (1970–) - Croatian retired football player

- Stipe Drviš (1973–) - Croatian boxer

- Garry Kasparov (1963–) - Soviet and Russian chess grandmaster; naturalised Croatian citizen[8]

- Andrija Kačić Miošić (1704–1760) - Croatian poet and monk

Twin towns/cities

Makarska is twinned with:

Friendly relationships:

Gallery

Adriatic coast on Makarska Riviera

Adriatic coast on Makarska Riviera- Franjo Tuđman monument

- Pelješčanka ferry

Makarska harbor

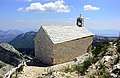

Makarska harbor Chapel on Biokovo

Chapel on Biokovo Makarska town center

Makarska town center Karst cliffs

Karst cliffs Red semi-submarine in Makarska harbour

Red semi-submarine in Makarska harbour

References

Notes

- "Population by Age and Sex, by Settlements, 2011 Census: Makarska". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2011. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. December 2012.

- Naklada Naprijed, The Croatian Adriatic Tourist Guide, pgs. 299-301, Zagreb (1999); ISBN 953-178-097-8

- Marušić 2017, p. 113.

- Marušić 2017, pp. 114–115.

- Marušić 2017, p. 115.

- Marušić 2017, p. 122.

- Nigel Thomas, K. Mikulan, Darko Pavlović. Axis Forces in Yugoslavia 1941-45, pg. 18, Osprey Publishing, 1995.

- French, Maddy (2014-02-28). "Chess champion Garry Kasparov granted Croatian citizenship". The Guardian.

Bibliography

- Marušić, Bartul (2017). "Opća i pravna povijest Makarske i primorja do austrijske vladavine" [General and legal history of Makarska and its littoral until Austrian rule] (PDF). Zbornik Radova Veleučilišta U Šibeniku (in Croatian) (3–4/2017): 111–131. Retrieved 6 May 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Sources and external links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Makarska. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Makarska. |

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- GCatholic - former cathedral

- Foster, Jane (3 June 2014). "Makarska, Croatia: Secret Seaside". The Telegraph. Retrieved 6 May 2019.