Radiolaria

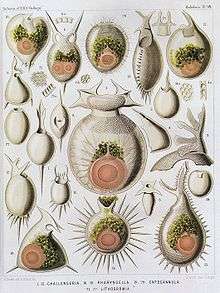

The Radiolaria, also called Radiozoa, are protozoa of diameter 0.1–0.2 mm that produce intricate mineral skeletons, typically with a central capsule dividing the cell into the inner and outer portions of endoplasm and ectoplasm. The elaborate mineral skeleton is usually made of silica.[1] They are found as zooplankton throughout the ocean, and their skeletal remains make up a large part of the cover of the ocean floor as siliceous ooze. Due to their rapid change as species, they represent an important diagnostic fossil found from the Cambrian onwards. Some common radiolarian fossils include Actinomma, Heliosphaera and Hexadoridium.

| Radiolaria | |

|---|---|

| |

| Radiolaria illustration from the Challenger Expedition 1873–76. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Clade: | SAR |

| Superphylum: | Retaria |

| Phylum: | Radiolaria Cavalier-Smith, 1987 |

| Classes | |

| |

Description

Radiolarians have many needle-like pseudopods supported by bundles of microtubules, which aid in the radiolarian's buoyancy. The cell nucleus and most other organelles are in the endoplasm, while the ectoplasm is filled with frothy vacuoles and lipid droplets, keeping them buoyant. The radiolarian can often contain symbiotic algae, especially zooxanthellae, which provide most of the cell's energy. Some of this organization is found among the heliozoa, but those lack central capsules and only produce simple scales and spines.

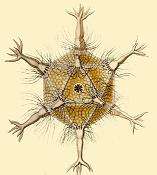

Some radiolarians are known for their resemblance to regular polyhedra, such as the icosahedron-shaped Circogonia icosahedra pictured.

Taxonomy

The radiolarians belong to the supergroup Rhizaria together with (amoeboid or flagellate) Cercozoa and (shelled amoeboid) Foraminifera.[2] Traditionally the radiolarians have been divided into four groups—Acantharea, Nassellaria, Spumellaria and Phaeodarea. Phaeodaria is however now considered to be a Cercozoan.[3][4] Nassellaria and Spumellaria both produce siliceous skeletons and were therefore grouped together in the group Polycystina. Despite some initial suggestions to the contrary, this is also supported by molecular phylogenies. The Acantharea produce skeletons of strontium sulfate and is closely related to a peculiar genus, Sticholonche (Taxopodida), which lacks an internal skeleton and was for long time considered a heliozoan. The Radiolaria can therefore be divided into two major lineages: Polycystina (Spumellaria + Nassellaria) and Spasmaria (Acantharia + Taxopodida).[5][6]

There are several higher-order groups that have been detected in molecular analyses of environmental data. Particularly, groups related to Acantharia[7] and Spumellaria.[8] These groups are so far completely unknown in terms of morphology and physiology and the radiolarian diversity is therefore likely to be much higher than what is currently known.

The relationship between the Foraminifera and Radiolaria is also debated. Molecular trees supports their close relationship—a grouping termed Retaria.[9] But whether they are sister lineages or if the Foraminifera should be included within the Radiolaria is not known.

Fossil record

The earliest known radiolaria date to the very start of the Cambrian period,[10][11][12][13] appearing in the same beds as the first small shelly fauna—they may even be terminal Precambrian in age. They have significant differences from later radiolaria, with a different silica lattice structure and few, if any, spikes on the test.[12] Ninety percent of radiolarian species are extinct. The skeletons, or tests, of ancient radiolarians are used in geological dating, including for oil exploration and determination of ancient climates.[14]

Higher concentrations of dissolved carbon dioxide (CO

2) in sea water dissolves their fine skeletons made of silica, destroying their delicate structure, seen as fractured scattered pieces under a microscope. This is linked to periods of heightened volcanic activity.

.jpg)

References

- Smalley, I.J. (1963). "Radiolarians:construction of spherical skeleton". Science. 140: 396–397. doi:10.1126/science.140.3565.396.

- Pawlowski J, Burki F (2009). "Untangling the phylogeny of amoeboid protists". J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 56 (1): 16–25. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2008.00379.x. PMID 19335771.

- Yuasa T, Takahashi O, Honda D, Mayama S (2005). "Phylogenetic analyses of the polycystine Radiolaria based on the 18s rDNA sequences of the Spumellarida and the Nassellarida". European Journal of Protistology. 41 (4): 287–298. doi:10.1016/j.ejop.2005.06.001.

- Nikolaev SI, Berney C, Fahrni JF, et al. (May 2004). "The twilight of Heliozoa and rise of Rhizaria, an emerging supergroup of amoeboid eukaryotes". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 (21): 8066–71. doi:10.1073/pnas.0308602101. PMC 419558. PMID 15148395.

- Krabberød AK, Bråte J, Dolven JK, et al. (2011). "Radiolaria divided into Polycystina and Spasmaria in combined 18S and 28S rDNA phylogeny". PLoS ONE. 6 (8): e23526. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...623526K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023526. PMC 3154480. PMID 21853146.

- Cavalier-Smith T (December 1993). "Kingdom protozoa and its 18 phyla". Microbiol. Rev. 57 (4): 953–94. doi:10.1128/mmbr.57.4.953-994.1993. PMC 372943. PMID 8302218.

- Decelle J, Suzuki N, Mahé F, de Vargas C, Not F (May 2012). "Molecular phylogeny and morphological evolution of the Acantharia (Radiolaria)". Protist. 163 (3): 435–50. doi:10.1016/j.protis.2011.10.002. PMID 22154393.

- Not F, Gausling R, Azam F, Heidelberg JF, Worden AZ (May 2007). "Vertical distribution of picoeukaryotic diversity in the Sargasso Sea". Environ. Microbiol. 9 (5): 1233–52. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01247.x. PMID 17472637.

- Cavalier-Smith T (July 1999). "Principles of protein and lipid targeting in secondary symbiogenesis: euglenoid, dinoflagellate, and sporozoan plastid origins and the eukaryote family tree". J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 46 (4): 347–66. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1999.tb04614.x. PMID 18092388.

- Chang, Shan; Feng, Qinglai; Zhang, Lei (14 August 2018). "New Siliceous Microfossils from the Terreneuvian Yanjiahe Formation, South China: The Possible Earliest Radiolarian Fossil Record". Journal of Earth Science. 29 (4): 912–919. doi:10.1007/s12583-017-0960-0.

- name=Zhang2019>Zhang, Ke; Feng, Qing-Lai (September 2019). "Early Cambrian radiolarians and sponge spicules from the Niujiaohe Formation in South China". Palaeoworld. 28 (3): 234–242. doi:10.1016/j.palwor.2019.04.001.

- Braun, Chen, Waloszek & Maas (2007), "First Early Cambrian Radiolaria", in Vickers-Rich, Patricia; Komarower, Patricia (eds.), The Rise and Fall of the Ediacaran Biota, Special publications, 286, London: Geological Society, pp. 143–149, doi:10.1144/SP286.10, ISBN 9781862392335, OCLC 156823511CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Maletz, Jörg (June 2017). "The identification of putative Lower Cambrian Radiolaria". Revue de Micropaléontologie. 60 (2): 233–240. doi:10.1016/j.revmic.2017.04.001.

- Zuckerman, L.D., Fellers, T.J., Alvarado, O., and Davidson, M.W. "Radiolarians", Molecular Expressions, Florida State University, 4 February 2004.

- Zettler, Linda A.; Sogin, ML; Caron, DA (1997). "Phylogenetic relationships between the Acantharea and the Polycystinea: A molecular perspective on Haeckel's Radiolaria". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94 (21): 11411–6. Bibcode:1997PNAS...9411411A. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.21.11411. PMC 23483. PMID 9326623.

- López-García P, Rodríguez-Valera F, Moreira D (January 2002). "Toward the monophyly of Haeckel's radiolaria: 18S rRNA environmental data support the sisterhood of polycystinea and acantharea". Mol. Biol. Evol. 19 (1): 118–121. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003976. PMID 11752197.

- Adl SM, Simpson AG, Farmer MA, et al. (2005). "The New Higher Level Classification of Eukaryotes with Emphasis on the Taxonomy of Protists". J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 52 (5): 399–451. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.00053.x. PMID 16248873.

- Haeckel, Ernst (2005). Art Forms from the Ocean: The Radiolarian Atlas of 1862. Munich; London: Prestel Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7913-3327-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Radiolaria. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Radiolaria |

- [1]Radiolarians

- Brodie, C. (February 2005). "Geometry and Pattern in Nature 3: The holes in radiolarian and diatom tests". Micscape (112). ISSN 1365-070X.

- Radiolaria.org

- Haeckel, Ernst (1862). Die Radiolarien (Rhizopoda radiaria). Berlin. Archived from the original on 2009-06-19. Retrieved 2007-09-07.

- Radiolaria—Droplet

- Tree Of Life—Radiolaria

- Boltovskoy, Demetrio; Anderson, O. Roger; Correa, Nancy M. (2016). Archibald, John M.; Simpson, Alastair G. B.; Slamovits, Claudio H.; Margulis, Lynn; Melkonian, Michael; Chapman, David J.; Corliss, John O. (eds.). Handbook of the Protists. Springer International Publishing. pp. 1–33. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-32669-6_19-1. ISBN 9783319326696.