Byzantine music

Byzantine music is the music of the Byzantine Empire. Originally it consisted of songs and hymns composed to Greek texts used for courtly ceremonials, during festivals, or as paraliturgical and liturgical music. The ecclesiastical forms of Byzantine music are the best known forms today, because different Orthodox traditions still identify with the heritage of Byzantine music, when their cantors sing monodic chant out of the traditional chant books such as sticherarion, which in fact consisted of five books, and the heirmologion.

| Music of Greece | |

|---|---|

| |

| General topics | |

| Genres | |

| Specific forms | |

| Media and performance | |

| Music awards |

|

| Music charts | |

| Music festivals | |

| Music media |

|

| Nationalistic and patriotic songs | |

| National anthem | "Hymn to Liberty" |

| Regional music | |

| Related areas | Cyprus, Pontus, Constantinople, South Italy |

| Regional styles |

|

Byzantine music did not disappear after the fall of Constantinople. Its traditions continued under the Patriarchate of Constantinople, which after the Ottoman conquest in 1453 was granted administrative responsibilities over all Orthodox Christians. During the decline of the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century, burgeoning splinter nations in the Balkans declared autonomy or "autocephaly" against the Ecumenical Patriarchate. The new self-declared patriarchates were independent nations defined by their religion.

In this context, Christian religious chant practiced in the Ottoman empire, Bulgaria, Serbia and Greece among other nations, was based on the historical roots of the art tracing back to the Byzantine Empire, while the music of the Patriarchate created during the Ottoman period was often regarded as "post-Byzantine". This explains why Byzantine music refers to several Orthodox Christian chant traditions of the Mediterranean and of the Caucasus practiced in recent history and even today, and this article cannot be limited to the music culture of the Byzantine past.

Imperial age

| Byzantine culture |

|---|

|

The tradition of eastern liturgical chant, encompassing the Greek-speaking world, developed in the Byzantine Empire from the establishment of its capital, Constantinople, in 330 until its fall in 1453. It is undeniably of composite origin, drawing on the artistic and technical productions of the classical Greek age and inspired by the monophonic vocal music that evolved in the early Greek Christian cities of Alexandria, Jerusalem, Antioch and Ephesus.[1] It was imitated by musicians of the 7th century to create Arab music as a synthesis of Byzantine and Persian music, and these exchanges were continued through the Ottoman Empire until Istanbul today.[2]

The term Byzantine music is sometimes associated with the medieval sacred chant of Christian Churches following the Constantinopolitan Rite. There is also an identification of "Byzantine music" with "Eastern Christian liturgical chant", which is due to certain monastic reforms, such as the Octoechos reform of the Quinisext Council (692) and the later reforms of the Stoudios Monastery under its abbots Sabas and Theodore.[3] The triodion created during the reform of Theodore was also soon translated into Slavonic, which required also the adaption of melodic models to the prosody of the language. Later, after the Patriarchate and Court had returned to Constantinople in 1261, the former cathedral rite was not continued, but replaced by a mixed rite, which used the Byzantine Round notation to integrate the former notations of the former chant books (Papadike). This notation had developed within the book sticherarion created by the Stoudios Monastery, but it was used for the books of the cathedral rites written in a period after the fourth crusade, when the cathedral rite was already abandoned at Constantinople. It is being discussed that in the Narthex of the Hagia Sophia an organ was placed for use in processions of the Emperor's entourage.[4]

The earliest sources and the tonal system of Byzantine music

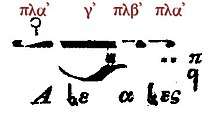

According to the chant manual "Hagiopolites" of 16 church tones (echoi), while the author of this treatise introduces to a tonal system of 10 echoi. Nevertheless, both schools have in common a set of 4 octaves (protos, devteros, tritos, and tetartos), each of them had a kyrios echos (authentic mode) with the finalis on the degree V of the mode, and a plagios echos (plagal mode) with the final note on the degree I. According to Latin theory, the resulting eight tones (octoechos) had been identified with the seven modes (octave species) and tropes (tropoi which meant the transposition of these modes). The names of the tropes like “Dorian” etc. had been also used in Greek chant manuals, but the names Lydian and Phrygian for the octaves of devteros and tritos had been sometimes exchanged. The Ancient Greek harmonikai was a Hellenist reception of the Pythagorean education programme defined as mathemata ("exercises"). Harmonikai was one of them. Today, chanters of the Christian Orthodox churches identify with the heritage of Byzantine music whose earliest composers are remembered by name since the 5th century. Compositions had been related to them, but they must be reconstructed by notated sources which date centuries later. The melodic neume notation of Byzantine music developed late since the 10th century, with the exception of an earlier ekphonetic notation, interpunction signs used in lectionaries, but modal signatures for the eight echoi can already be found in fragments (papyri) of monastic hymn books (tropologia) dating back to the 6th century.[5]

Amid the rise of Christian civilization within Hellenism, many concepts of knowledge and education survived during the imperial age, when Christianity became the official religion.[6] The Pythagorean sect and music as part of the four "cyclical exercises" (ἐγκύκλια μαθήματα) that preceded the Latin quadrivium and science today based on mathematics, established mainly among Greeks in southern Italy (at Taranto and Crotone). Greek anachoretes of the early Middle Ages did still follow this education. The Calabrian Cassiodorus founded Vivarium where he translated Greek texts (science, theology and the Bible), and John of Damascus who learnt Greek from a Calabrian monk Kosmas, a slave in the household of his privileged father at Damascus, mentioned mathematics as part of the speculative philosophy.[7]

Διαιρεῖται δὲ ἡ φιλοσοφία εἰς θεωρητικὸν καὶ πρακτικόν, τὸ θεωρητικὸν εἰς θεολογικόν, φυσικόν, μαθηματικόν, τὸ δὲ πρακτικὸν εἰς ἠθικόν, οἰκονομικόν, πολιτικόν.[8]

According to him philosophy was divided into theory (theology, physiology, mathematics) and practice (ethics, economy, politics), and the Pythagorean heritage was part of the former, while only the ethic effects of music were relevant in practice. The mathematic science harmonics was usually not mixed with the concrete topics of a chant manual.

Nevertheless, Byzantine music is modal and entirely dependent on the Ancient Greek concept of harmonics.[9] Its tonal system is based on a synthesis with ancient Greek models, but we have no sources left that explain to us how this synthesis was done. Carolingian cantors could mix the science of harmonics with a discussion of church tones, named after the ethnic names of the octave species and their transposition tropes, because they invented their own octoechos on the basis of the Byzantine one. But they made no use of earlier Pythagorean concepts that had been fundamental for Byzantine music, including:

| Greek Reception | Latin Reception |

|---|---|

| the division of the tetrachord by three different intervals | the division by two different intervals (twice a tone and one half tone) |

| the temporary change of the genus (μεταβολὴ κατὰ γένος) | the official exclusion of the enharmonic and chromatic genus, although its use was rarely commented in a polemic way |

| the temporary change of the echos (μεταβολὴ κατὰ ἦχον) | a definitive classification according to one church tone |

| the temporary transposition (μεταβολὴ κατὰ τόνον) | absonia (Musica and Scolica enchiriadis, Berno of Reichenau, Frutolf of Michelsberg), although it was known since Boethius' wing diagramme |

| the temporary change of the tone system (μεταβολὴ κατὰ σύστημα) | no alternative tone system, except the explanation of absonia |

| the use of at least three tone systems (triphonia, tetraphonia, heptaphonia) | the use of the systema teleion (heptaphonia), relevance of Dasia system (tetraphonia) outside polyphony and of the triphonia mentioned in the Cassiodorus quotation (Aurelian) unclear |

| the microtonal attraction of mobile degrees (κινούμενοι) by fixed degrees (ἑστώτες) of the mode (echos) and its melos, not of the tone system | the use of dieses (attracted are E, a, and b natural within a half tone), since Boethius until Guido of Arezzo's concept of mi |

It is not evident by the sources, when exactly the position of the minor or half tone moved between the devteros and tritos. It seems that the fixed degrees (hestotes) became part of a new concept of the echos as melodic mode (not simply octave species), after the echoi had been called by the ethnic names of the tropes.

Instruments within the Byzantine Empire

The 9th century Persian geographer Ibn Khurradadhbih (d. 911); in his lexicographical discussion of instruments cited the lyra (lūrā) as the typical instrument of the Byzantines along with the urghun (organ), shilyani (probably a type of harp or lyre) and the salandj (probably a bagpipe).[11]

The first of these, the early bowed stringed instrument known as the Byzantine lyra, would come to be called the lira da braccio,[12] in Venice, where it is considered by many to have been the predecessor of the contemporary violin, which later flourished there.[13] The bowed "lyra" is still played in former Byzantine regions, where it is known as the Politiki lyra (lit. "lyra of the City" i.e. Constantinople) in Greece, the Calabrian lira in Southern Italy, and the Lijerica in Dalmatia.

The second instrument, the Hydraulis, originated in the Hellenistic world and was used in the Hippodrome in Constantinople during races.[14][15] A pipe organ with "great leaden pipes" was sent by the emperor Constantine V to Pepin the Short King of the Franks in 757. Pepin's son Charlemagne requested a similar organ for his chapel in Aachen in 812, beginning its establishment in Western church music.[15] Despite this, the Byzantines never used pipe organs and kept the flute-sounding Hydraulis until the Fourth Crusade.

The final Byzantine instrument, the aulos, was a double-reeded woodwind like the modern oboe or Armenian duduk. Other forms include the plagiaulos (πλαγίαυλος, from πλάγιος, plagios "sideways"), which resembled the flute,[16] and the askaulos (ἀσκαυλός from ἀσκός askos "wine-skin"), a bagpipe.[17] These bagpipes, also known as Dankiyo (from ancient Greek: To angeion (Τὸ ἀγγεῖον) "the container"), had been played even in Roman times. Dio Chrysostom wrote in the 1st century of a contemporary sovereign (possibly Nero) who could play a pipe (tibia, Roman reedpipes similar to Greek aulos) with his mouth as well as by tucking a bladder beneath his armpit.[18] The bagpipes continued to be played throughout the empire's former realms down to the present. (See Balkan Gaida, Greek Tsampouna, Pontic Tulum, Cretan Askomandoura, Armenian Parkapzuk, Zurna and Romanian Cimpoi.)

Other commonly used instruments used in Byzantine Music include the Kanonaki, Oud, Laouto, Santouri, Toubeleki, Tambouras, Defi Tambourine, Çifteli (which was known as Tamburica in Byzantine times), Lyre, Kithara, Psaltery, Saz, Floghera, Pithkiavli, Kavali, Seistron, Epigonion (the ancestor of the Santouri), Varviton (the ancestor of the Oud and a variation of the Kithara), Crotala, Bowed Tambouras (similar to Byzantine Lyra), Šargija, Monochord, Sambuca, Rhoptron, Koudounia, perhaps the Lavta and other instruments used before the 4th Crusade that are no longer played today. These instruments are unknown at this time.

Acclamations at the court and the ceremonial book

Secular music existed and accompanied every aspect of life in the empire, including dramatic productions, pantomime, ballets, banquets, political and pagan festivals, Olympic games, and all ceremonies of the imperial court. It was, however, regarded with contempt, and was frequently denounced as profane and lascivious by some Church Fathers.[19]

.jpg)

Another genre that lies between liturgical chant and court ceremonial are the so-called polychronia (πολυχρονία) and acclamations (ἀκτολογία).[20] The acclamations were sung to announce the entrance of the Emperor during representative receptions at the court, into the hippodrome or into the cathedral. They can be different from the polychronia, ritual prayers or ektenies for present political rulers and are usually answered by a choir with formulas such as "Lord protect" (κύριε σῶσον) or "Lord have mercy on us/them" (κύριε ἐλέησον).[21] The documented polychronia in books of the cathedral rite allow a geographical and a chronological classification of the manuscript and they are still used during ektenies of the divine liturgies of national Orthodox ceremonies today. The hippodrome was used for a traditional feast called Lupercalia (15 February), and on this occasion the following acclamation was celebrated:[22]

| Claqueurs: | Lord, protect the Master of the Romans. | Οἱ κράκται· | Κύριε, σῶσον τοὺς δεσπότας τῶν Ῥωμαίων. |

| The people: | Lord, protect (X3). | ὁ λαός ἐκ γ'· | Κύριε, σῶσον. |

| Claqueurs: | Lord, protect to whom they gave the crown. | Οἱ κράκται· | Κύριε, σῶσον τοὺς ἐκ σοῦ ἐστεμμένους. |

| The people: | Lord, protect (X3). | ὁ λαός ἐκ γ'· | Κύριε, σῶσον. |

| Claqueurs: | Lord, protect the Orthodox power. | Οἱ κράκται· | Κύριε, σῶσον ὀρθόδοξον κράτος· |

| The people: | Lord, protect (X3). | ὁ λαός ἐκ γ'· | Κύριε, σῶσον. |

| Claqueurs: | Lord, protect the renewal of the annual cycles. | Οἱ κράκται· | Κύριε, σῶσον τὴν ἀνακαίνησιν τῶν αἰτησίων. |

| The people: | Lord, protect (X3). | ὁ λαός ἐκ γ'· | Κύριε, σῶσον. |

| Claqueurs: | Lord, protect the wealth of the subjects. | Οἱ κράκται· | Κύριε, σῶσον τὸν πλοῦτον τῶν ὑπηκόων· |

| The people: | Lord, protect (X3). | ὁ λαός ἐκ γ'· | Κύριε, σῶσον. |

| Claqueurs: | May the Creator and Master of all things make long your years with the Augustae and the Porphyrogeniti. | Οἱ κράκται· | Ἀλλ᾽ ὁ πάντων Ποιητὴς καὶ Δεσπότης τοὺς χρόνους ὑμῶν πληθύνει σὺν ταῖς αὐγούσταις καὶ τοῖς πορφυρογεννήτοις. |

| The people: | Lord, protect (X3). | ὁ λαός ἐκ γ'· | Κύριε, σῶσον. |

| Claqueurs: | Listen, God, to your people. | Οἱ κράκται· | Εἰσακούσει ὁ Θεὸς τοῦ λαοῦ ἡμῶν· |

| The people: | Lord, protect (X3). | ὁ λαός ἐκ γ'· | Κύριε, σῶσον. |

The main source about court ceremonies is an incomplete compilation in a 10th-century manuscript that organised parts of a treatise Περὶ τῆς Βασιλείου Τάξεως ("On imperial ceremonies") ascribed to Emperor Constantine VII, but in fact compiled by different authors who contributed with additional ceremonies of their period.[23] In its incomplete form chapter 1–37 of book I describe processions and ceremonies on religious festivals (many lesser ones, but especially great feasts such as the Elevation of the Cross, Christmas, Theophany, Palm Sunday, Good Friday, Easter and Ascension Day and feasts of saints including St Demetrius, St Basil etc. often extended over many days), while chapter 38–83 describe secular ceremonies or rites of passage such as coronations, weddings, births, funerals, or the celebration of war triumphs.[24] For the celebration of Theophany the protocol begins to mention several stichera and their echoi (ch. 3) and who had to sing them:

Δοχὴ πρώτη, τῶν Βενέτων, φωνὴ ἢχ. πλαγ. δ`. « Σήμερον ὁ συντρίψας ἐν ὕδασι τὰς κεφαλὰς τῶν δρακόντων τὴν κεφαλὴν ὑποκλίνει τῷ προδρόμῳ φιλανθρώπως. » Δοχἠ β᾽, τῶν Πρασίνων, φωνὴ πλαγ. δ'· « Χριστὸς ἁγνίζει λουτρῷ ἁγίῳ τὴν ἐξ ἐθνῶν αὐτοῦ Ἐκκλησίαν. » Δοχὴ γ᾽, τῶν Βενέτων, φωνἠ ἤχ. πλαγ. α'· « Πυρὶ θεότητος ἐν Ἰορδάνῃ φλόγα σβεννύει τῆς ἁμαρτίας. »[25]

These protocols gave rules for imperial progresses to and from certain churches at Constantinople and the imperial palace,[26] with fixed stations and rules for ritual actions and acclamations from specified participants (the text of acclamations and processional troparia or kontakia, but also heirmoi are mentioned), among them also ministers, senate members, leaders of the "Blues" (Venetoi) and the "Greens" (Prasinoi)—chariot teams during the hippodrome's horse races. They had an important role during court ceremonies.[27] The following chapters (84–95) are taken from a 6th-century manual by Peter the Patrician. They rather describe administrative ceremonies such as the appointment of certain functionaries (ch. 84,85), investitures of certain offices (86), the reception of ambassadors and the proclamation of the Western Emperor (87,88), the reception of Persian ambassadors (89,90), Anagorevseis of certain Emperors (91–96), the appointment of the senate's proedros (97). The "palace order" did not only prescribe the way of movements (symbolic or real) including on foot, mounted, by boat, but also the costumes of the celebrants and who has to perform certain acclamations. The emperor often plays the role of Christ and the imperial palace is chosen for religious rituals, so that the ceremonial book brings the sacred and the profane together. Book II seems to be less normative and was obviously not compiled from older sources like book I, which often mentioned outdated imperial offices and ceremonies, it rather describes particular ceremonies as they had been celebrated during particular imperial receptions during the Macedonian renaissance.

The Desert Fathers and urban monasticism

Two concepts must be understood to appreciate fully the function of music in Byzantine worship and they were related to a new form of urban monasticism, which even formed the representative cathedral rites of the imperial ages, which had to baptise many catechumens.

The first, which retained currency in Greek theological and mystical speculation until the dissolution of the empire, was the belief in the angelic transmission of sacred chant: the assumption that the early Church united men in the prayer of the angelic choirs. It was partly based on the Hebrew fundament of Christian worship, but in the particular reception of St. Basil of Caesarea's divine liturgy. John Chrysostom, since 397 Archbishop of Constantinople, abridged the long formular of Basil's divine liturgy for the local cathedral rite.

The notion of angelic chant is certainly older than the Apocalypse account (Revelation 4:8–11), for the musical function of angels as conceived in the Old Testament is brought out clearly by Isaiah (6:1–4) and Ezekiel (3:12). Most significant in the fact, outlined in Exodus 25, that the pattern for the earthly worship of Israel was derived from heaven. The allusion is perpetuated in the writings of the early Fathers, such as Clement of Rome, Justin Martyr, Ignatius of Antioch, Athenagoras of Athens, John Chrysostom and Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite. It receives acknowledgement later in the liturgical treatises of Nicolas Kavasilas and Symeon of Thessaloniki.[28]

The second, less permanent, concept was that of koinonia or "communion". This was less permanent because, after the fourth century, when it was analyzed and integrated into a theological system, the bond and "oneness" that united the clergy and the faithful in liturgical worship was less potent. It is, however, one of the key ideas for understanding a number of realities for which we now have different names. With regard to musical performance, this concept of koinonia may be applied to the primitive use of the word choros. It referred, not to a separate group within the congregation entrusted with musical responsibilities, but to the congregation as a whole. St. Ignatius wrote to the Church in Ephesus in the following way:

You must every man of you join in a choir so that being harmonious and in concord and taking the keynote of God in unison, you may sing with one voice through Jesus Christ to the Father, so that He may hear you and through your good deeds recognize that you are parts of His Son.

A marked feature of liturgical ceremony was the active part taken by the people in its performance, particularly in the recitation or chanting of hymns, responses and psalms. The terms choros, koinonia and ekklesia were used synonymously in the early Byzantine Church. In Psalms 149 and 150, the Septuagint translated the Hebrew word machol (dance) by the Greek word choros Greek: χορός. As a result, the early Church borrowed this word from classical antiquity as a designation for the congregation, at worship and in song in heaven and on earth both.

Concerning the practice of psalm recitation, the recitation by a congregation of educated chanters is already testified by the soloistic recitation of abridged psalms by the end of the 4th century. Later it was called prokeimenon. Hence, there was an early practice of simple psalmody, which was used for the recitation of canticles and the psalter, and usually Byzantine psalters have the 15 canticles in an appendix, but the simple psalmody itself was not notated before the 13th century, in dialogue or papadikai treatises preceding the book sticheraria.[29] Later books, like the akolouthiai and some psaltika, also contain the elaborated psalmody, when a protopsaltes recited just one or two psalm verses. Between the recited psalms and canticles troparia were recited according to the same more or less elaborated psalmody. This context relates antiphonal chant genres including antiphona (kind of introits), trisagion and its substitutes, prokeimenon, allelouiarion, the later cherubikon and its substitutes, the koinonikon cycles as they were created during the 9th century. In most of the cases they were simply troparia and their repetitions or segments were given by the antiphonon, whether it was sung or not, its three sections of the psalmodic recitation were separated by the troparion.

The recitation of the biblical odes

The fashion in all cathedral rites of the Mediterranean was a new emphasis on the psalter. In older ceremonies before Christianity became the religion of empires, the recitation of the biblical odes (mainly taken from the Old Testament) was much more important. They did not disappear in certain cathedral rites such as the Milanese and the Constantinopolitan rite.

Before long, however, a clericalizing tendency soon began to manifest itself in linguistic usage, particularly after the Council of Laodicea, whose fifteenth Canon permitted only the canonical psaltai, "chanters:", to sing at the services. The word choros came to refer to the special priestly function in the liturgy – just as, architecturally speaking, the choir became a reserved area near the sanctuary—and choros eventually became the equivalent of the word kleros (the pulpits of two or even five choirs).

The nine canticles or odes according to the psalter were:

- (1) The Song of the sea (Exodus 15:1–19);

- (2) The Song of Moses (Deuteronomy 32:1–43);

- (3) – (6) The prayers of Hannah, Habakkuk, Isaiah, Jonah (1 Kings [1 Samuel] 2:1–10; Habakkuk 3:1–19; Isaiah 26:9–20; Jonah 2:3–10);

- (7) – (8) The Prayer of Azariah and Song of the Three Holy Children (Apoc. Daniel 3:26–56 and 3:57–88);

- (9) The Magnificat and the Benedictus (Luke 1:46–55 and 68–79).

and in Constantinople they were combined in pairs against this canonical order:[30]

- Ps. 17 with troparia Ἀλληλούϊα and Μνήσθητί μου, κύριε.

- (1) with troparion Tῷ κυρίῳ αἴσωμεν, ἐνδόξως γὰρ δεδόξασται.

- (2) with troparion Δόξα σοι, ὁ θεός. (Deut. 32:1–14) Φύλαξόν με, κύριε. (Deut. 32:15–21) Δίκαιος εἶ, κύριε, (Deut. 32:22–38) Δόξα σοι, δόξα σοι. (Deut. 32:39–43) Εἰσάκουσόν μου, κύριε. (3)

- (4) & (6) with troparion Οἰκτείρησόν με, κύριε.

- (3) & (9a) with troparion Ἐλέησόν με, κύριε.

- (5) & Mannaseh (apokr. 2 Chr 33) with troparion Ἰλάσθητί μοι, κύριε.

- (7) which has a refrain in itself.

The troparion

The common term for a short hymn of one stanza, or one of a series of stanzas, is troparion. As a refrain interpolated between psalm verses it had the same function as the antiphon in Western plainchant. The simplest troparion was probably "allelouia", and similar to troparia like the trisagion or the cherubikon or the koinonika a lot of troparia became a chant genre of their own.

A famous example, whose existence is attested as early as the 4th century, is the Easter Vespers hymn, Phos Hilaron ("O Resplendent Light"). Perhaps the earliest set of troparia of known authorship are those of the monk Auxentios (first half of the 5th century), attested in his biography but not preserved in any later Byzantine order of service. Another, O Monogenes Yios ("Only Begotten Son"), ascribed to the emperor Justinian I (527–565), followed the doxology of the second antiphonon at the beginning of the Divine Liturgy.

Romanos the Melodist, the kontakion, and the Hagia Sophia

The development of large scale hymnographic forms begins in the fifth century with the rise of the kontakion, a long and elaborate metrical sermon, reputedly of Syriac origin, which finds its acme in the work of St. Romanos the Melodist (6th century). This dramatic homily which could treat various subjects, theological and hagiographical ones as well as imperial propaganda, comprises some 20 to 30 stanzas (oikoi "houses") and was sung in a rather simple style with emphasise on the understanding of the recent texts.[31] The earliest notated versions in Slavic kondakar's (12th century) and Greek kontakaria-psaltika (13th century), however, are in a more elaborate style (also rubrified idiomela), and were probably sung since the ninth century, when kontakia were reduced to the prooimion (introductory verse) and first oikos (stanza).[32] Romanos' own recitation of all the numerous oikoi must have been much simpler, but the most interesting question of the genre are the different functions that kontakia once had. Romanos' original melodies were not delivered by notated sources dating back to the 6th century, the earliest notated source is the Tipografsky Ustav written about 1100. Its gestic notation was different from Middle Byzantine notation used in Italian and Athonite Kontakaria of the 13th century, where the gestic signs (cheironomiai) became integrated as “great signs”. During the period of psaltic art (14th and 15th centuries), the interest of kalophonic elaboration was focussed on one particular kontakion which was still celebrated: the Akathist hymn. An exception was John Kladas who contributed also with kalophonic settings of other kontakia of the repertoire.

Some of them had a clear liturgical assignation, others not, so that they can only be understood from the background of the later book of ceremonies. Some of Romanos creations can be even regarded as political propaganda in connection with the new and very fast reconstruction of the famous Hagia Sophia by Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles. A quarter of Constantinople had been burnt down during a civil war. Justinian had ordered a massacre at the hippodrome, because his imperial antagonists who were affiliated to the former dynasty, had been organised as a chariot team.[33] Thus, he had place for the creation of a huge park with a new cathedral in it, which was larger than any church built before as Hagia Sophia. He needed a kind of mass propaganda to justify the imperial violence against the public. In the kontakion "On earthquakes and conflagration" (H. 54), Romanos interpreted the Nika riot as a divine punishment, which followed in 532 earlier ones including earthquakes (526–529) and a famine (530):[34]

| The city was buried beneath these horrors and cried in great sorrow. | Ὑπὸ μὲν τούτων τῶν δεινῶν κατείχετο ἡ πόλις καὶ θρῆνον εἶχε μέγα· |

| Those who feared God stretched their hands out to him, | Θεὸν οἱ δεδιότες χεῖρας ἐξέτεινον αὐτῷ |

| begging for compassion and an end to the terror. | ἐλεημοσύνην ἐξαιτοῦντες παρ᾽ αὐτοῦ καὶ τῶν κακῶν κατάπαυσιν· |

| Reasonably, the emperor—and his empress—were in these ranks, | σὺν τούτοις δὲ εἰκότως ἐπηύχετο καὶ ὁ βασιλεύων |

| their eyes lifted in hope toward the Creator: | ἀναβλέψας πρὸς τὸν πλάστην —σὺν τούτῳ δὲ σύνευνος ἡ τούτου— |

| "Grant me victory", he said, "just as you made David | Δός μοι, βοῶν, σωτήρ, ὡς καὶ τῷ Δαυίδ σου |

| victorious over Goliath. You are my hope. | τοῦ νικῆσαι Γολιάθ· σοὶ γὰρ ἐλπίζω· |

| Rescue, in your mercy, your loyal people | σῶσον τὸν πιστὸν λαόν σου ὡς ἐλεήμων, |

| and grant them eternal life." | οἶσπερ καὶ δώσῃς ζωὴν τὴν αἰώνιον.(H. 54.18) |

According to Johannes Koder the kontakion was celebrated the first time during Lenten period in 537, about ten months before the official inauguration of the new built Hagia Sophia on 27 December.

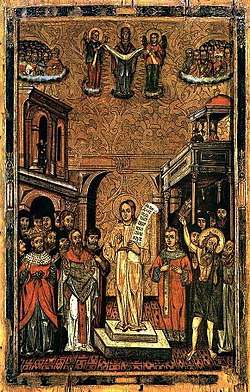

Changes in architecture and liturgy, and the introduction of the cherubikon

During the second half of the sixth century, there was a change in Byzantine sacred architecture, because the altar used for the preparation of the eucharist had been removed from the bema. It was placed in a separated room called "prothesis" (πρόθεσις). The separation of the prothesis where the bread was consecrated during a separated service called proskomide, required a procession of the gifts at the beginning of the second eucharist part of the divine liturgy. The troparion "Οἱ τὰ χερουβεὶμ", which was sung during the procession, was often ascribed to Emperor Justin II, but the changes in sacred architecture were definitely traced back to his time by archaeologists.[35] Concerning the Hagia Sophia, which was constructed earlier, the procession was obviously within the church.[36] It seems that the cherubikon was a prototype of the Western chant genre offertory.[37]

With this change came also the dramaturgy of the three doors in a choir screen before the bema (sanctuary). They were closed and opened during the ceremony.[38] Outside Constantinople these choir or icon screens of marble were later replaced by iconostaseis. Antonin, a Russian monk and pilgrim of Novgorod, described the procession of choirs during Orthros and the divine liturgy, when he visited Constantinople in December 1200:

When they sing Lauds at Hagia Sophia, they sing first in the narthex before the royal doors; then they enter to sing in the middle of the church; then the gates of Paradise are opened and they sing a third time before the altar. On Sundays and feastdays the Patriarch assists at Lauds and at the Liturgy; at this time he blesses the singers from gallery, and ceasing to sing, they proclaim the polychronia; then they begin to sing again as harmoniously and as sweetly as the angels, and they sing in this fashion until the Liturgy. After Lauds they put off their vestments and go out to receive the blessing of the Patriarch; then the preliminary lessons are read in the ambo; when these are over the Liturgy begins, and at the end of the service the chief priest recites the so-called prayer of the ambo within the sanctuary while the second priest recites in the church, beyond the ambo; when they have finished the prayer, both bless the people. Vespers are said in the same fashion, beginning at an early hour.[39]

Monastic reforms in Constantinople and Jerusalem

By the end of the seventh century with the reform of 692, the kontakion, Romanos' genre was overshadowed by a certain monastic type of homiletic hymn, the canon and its prominent role it played within the cathedral rite of the Patriarchate of Jerusalem. Essentially, the canon, as it is known since 8th century, is a hymnodic complex composed of nine odes that were originally related, at least in content, to the nine Biblical canticles and to which they were related by means of corresponding poetic allusion or textual quotation (see the section about the biblical odes). Out of the custom of canticle recitation, monastic reformers at Constantinople, Jerusalem and Mount Sinai developed a new homiletic genre whose verses in the complex ode meter were composed over a melodic model: the heirmos.[40]

During the 7th century kanons at the Patriarchate of Jerusalem still consisted of the two or three odes throughout the year cycle, and often combined different echoi. The form common today of nine or eight odes was introduced by composers within the school of Andrew of Crete at Mar Saba. The nine odes of the kanon were dissimilar by their metrum. Consequently, an entire heirmos comprises nine independent melodies (eight, because the second ode was often omitted outside Lenten period), which are united musically by the same echos and its melos, and sometimes even textually by references to the general theme of the liturgical occasion—especially in acrosticha composed over a given heirmos, but dedicated to a particular day of the menaion. Until the 11th century, the common book of hymns was the tropologion and it had no other musical notation than a modal signature and combined different hymn genres like troparion, sticheron, and canon.

The earliest tropologion was already composed by Severus of Antioch, Paul of Edessa and Ioannes Psaltes at the Patriarchate of Antioch between 512 and 518. Their tropologion has only survived in Syriac translation and revised by Jacob of Edessa.[41] The tropologion was continued by Sophronius, Patriarch of Jerusalem, but especially by Andrew of Crete's contemporary Germanus I, Patriarch of Constantinople who represented as a gifted hymnographer not only an own school, but he became also very eager to realise the purpose of this reform since 705, although its authority was questioned by iconoclast antagonists and only established in 787. After the octoechos reform of the Quinisext Council in 692, monks at Mar Saba continued the hymn project under Andrew's instruction, especially by his most gifted followers John of Damascus and Cosmas of Jerusalem. These various layers of the Hagiopolitan tropologion since the 5th century have mainly survived in a Georgian type of tropologion called "Iadgari" whose oldest copies can be dated back to the 9th century.[42]

Today the second ode is usually omitted (while the great kanon attributed to John of Damascus includes it), but medieval heirmologia rather testify the custom, that the extremely strict spirit of Moses' last prayer was especially recited during Lenten tide, when the number of odes was limited to three odes (triodion), especially patriarch Germanus I contributed with many own compositions of the second ode. According to Alexandra Nikiforova only two of 64 canons composed by Germanus I are present in the current print editions, but manuscripts have transmitted his hymnographic heritage.[43]

The monastic reform of the Stoudites and their notated chant books

During the 9th-century reforms of the Stoudios Monastery, the reformers favoured Hagiopolitan composers and customs in their new notated chant books heirmologion and sticherarion, but they also added substantial parts to the tropologion and re-organised the cycle of movable and immovable feasts (especially Lent, the triodion, and its scriptural lessons).[44] The trend is testified by a 9th-century tropologion of the Saint Catherine's Monastery which is dominated by contributions of Jerusalem.[45] Festal stichera, accompanying both the fixed psalms at the beginning and end of Hesperinos and the psalmody of the Orthros (the Ainoi) in the Morning Office, exist for all special days of the year, the Sundays and weekdays of Lent, and for the recurrent cycle of eight weeks in the order of the modes beginning with Easter. Their melodies were originally preserved in the tropologion. During the 10th century two new notated chant books were created at the Stoudios Monastery, which were supposed to replace the tropologion:

- the sticherarion, consisting of the idiomela in the menaion (the immoveable cycle between September and August), the triodion and the pentekostarion (the moveable cycle around the holy week), and the short version of octoechos (hymns of the Sunday cycle starting with Saturday evening) which sometimes contained a limited number of model troparia (prosomoia). A rather bulky volume called "great octoechos" or "parakletike" with the weekly cycle appeared first in the middle of the tenth century as a book of its own.[46]

- the heirmologion, which was composed in eight parts for the eight echoi, and further on either according to the canons in liturgical order (KaO) or according to the nine odes of the canon as a subdivision into 9 parts (OdO).

These books were not only provided with musical notation, with respect to the former tropologia they were also considerably more elaborated and varied as a collection of various local traditions. In practice it meant that only a small part of the repertory was really chosen to be sung during the divine services.[47] Nevertheless, the form tropologion was used until the 12th century, and many later books which combined octoechos, sticherarion and heirmologion, rather derive from it (especially the usually unnotated Slavonic osmoglasnik which was often divided in two parts called "pettoglasnik", one for the kyrioi, another for the plagioi echoi).

The old custom can be studied on the basis of the 9th-century tropologion ΜΓ 56+5 from Sinai which was still organised according to the old tropologion beginning with the Christmas and Epiphany cycle (not with 1 September) and without any separation of the movable cycle.[48] The new Studite or post-Studite custom established by the reformers was that each ode consists of an initial troparion, the heirmos, followed by three, four or more troparia from the menaion, which are the exact metrical reproductions of the heirmos (akrostics), thereby allowing the same music to fit all troparia equally well. The combination of Constantinopolitan and Palestine customs must be also understood on the base of the political history.[49]

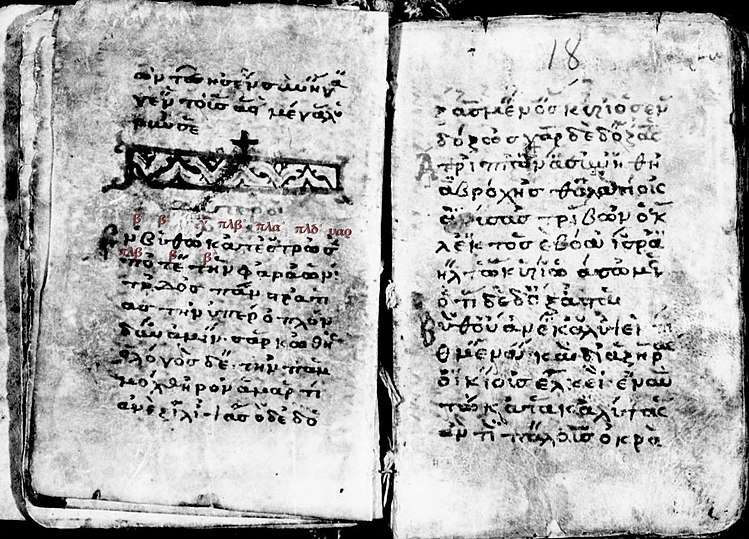

.jpg)

Especially the first generation around Theodore Studites and Joseph the Confessor, and the second around Joseph the Hymnographer suffered from the first and the second crisis of iconoclasm. The community around Theodore could revive monastic life at the abandoned Stoudios Monastery, but he had to leave Constantinople frequently in order to escape political persecution. During this period, the Patriarchates of Jerusalem and Alexandria (especially Sinai) remained centres of the hymnographic reform. Concerning the Old Byzantine notation, Constantinople and the area between Jerusalem and Sinai can be clearly distinguished. The earliest notation used for the books sticherarion and was theta notation, but it was soon replaced by palimpsests with more detailed forms between Coislin (Palestine) and Chartres notation (Constantinople).[50] Although it was correct that the Studites in Constantinople established a new mixed rite, its customs remained different from those of the other Patriarchates which were located outside the Empire.

On the other hand, Constantinople as well as other parts of the Empire like Italy encouraged also privileged women to found female monastic communities and certain hegumeniai also contributed to the hymnographic reform.[51] The basic repertoire of the newly created cycles the immovable menaion, the movable triodion and pentekostarion and the week cycle of parakletike and Orthros cycle of the eleven stichera heothina and their lessons are the result of a redaction of the tropologion which started with the generation of Theodore the Studite and ended during the Macedonian Renaissance under the emperors Leo VI (the stichera heothina are traditionally ascribed to him) and Constantine VII (the exaposteilaria anastasima are ascribed to him).

The cyclic organization of lectionaries

Another project of the Studites' reform was the organisation of the New Testament (Epistle, Gospel) reading cycles, especially its hymns during the period of the triodion (between the pre-Lenten Meatfare Sunday called "Apokreo" and the Holy Week).[52] Older lectionaries had been often completed by the addition of ekphonetic notation and of reading marks which indicate the readers where to start (ἀρχή) and to finish (τέλος) on a certain day.[53] The Studites also created a typikon—a monastic one which regulated the cœnobitic life of the Stoudios Monastery and granted its autonomy in resistance against iconoclast Emperors, but they had also an ambitious liturgical programme. They imported Hagiopolitan customs (of Jerusalem) like the Great Vesper, especially for the movable cycle between Lent and All Saints (triodion and pentekostarion), including a Sunday of Orthodoxy which celebrated the triumph over iconoclasm on the first Sunday of Lent.[54]

Unlike the current Orthodox custom Old Testament readings were particular important during Orthros and Hesperinos in Constantinople since the 5th century, while there was no one during the divine liturgy.[55] The Great Vespers according to Studite and post-Studite custom (reserved for just a few feasts like the Sunday of Orthodoxy) were quite ambitious. The evening psalm 140 (kekragarion) was based on simple psalmody, but followed by florid coda of a soloist (monophonaris). A melismatic prokeimenon was sung by him from the ambo, it was followed by three antiphons (Ps 114–116) sung by the choirs, the third used the trisagion or the usual anti-trisagion as a refrain, and an Old Testament reading concluded the prokeimenon.[56]

The Hagiopolites treatise

The earliest chant manual pretends right at the beginning that John of Damascus was its author. Its first edition was based on a more or less complete version in a 14th-century manuscript,[57] but the treatise was probably created centuries earlier as part of the reform redaction of the tropologia by the end of the 8th century, after Irene's Council of Nikaia had confirmed the octoechos reform of 692 in 787. It fits well to the later focus on Palestine authors in the new chant book heirmologion.

Concerning the octoechos, the Hagiopolitan system is characterised as a system of eight diatonic echoi with two additional phthorai (nenano and nana) which were used by John of Damascus and Cosmas, but not by Joseph the Confessor who obviously preferred the diatonic mele of plagios devteros and plagios tetartos.[58]

It also mentions an alternative system of the Asma (the cathedral rite was called ἀκολουθία ᾀσματική) that consisted of 4 kyrioi echoi, 4 plagioi, 4 mesoi, and 4 phthorai. It seems that until the time, when the Hagiopolites was written, the octoechos reform did not work out for the cathedral rite, because singers at the court and at the Patriarchate still used a tonal system of 16 echoi, which was obviously part of the particular notation of their books: the asmatikon and the kontakarion or psaltikon.

But neither any 9th-century Constantinopolitan chant book nor an introducing treatise that explains the fore-mentioned system of the Asma, have survived. Only a 14th-century manuscript of Kastoria testifies cheironomic signs used in these books, which are transcribed in longer melodic phrases by the notation of the contemporary sticherarion, the middle Byzantine Round notation.

The transformation of the kontakion

The former genre and glory of Romanos' kontakion was not abandoned by the reformers, even contemporary poets in a monastic context continued to compose new liturgical kontakia (mainly for the menaion), it likely preserved a modality different from Hagiopolitan oktoechos hymnography of the sticherarion and the heirmologion.

But only a limited number of melodies or kontakion mele had survived. Some of them were rarely used to compose new kontakia, other kontakia which became the model for eight prosomoia called “kontakia anastasima” according to the oktoechos, had been frequently used. The kontakion ὁ ὑψωθεῖς ἐν τῷ σταυρῷ for the feast of cross exaltation (14 September) was not the one chosen for the prosomoion of the kontakion anastasimon in the same echos, it was actually the kontakion ἐπεφάνης σήμερον for Theophany (6 January). But nevertheless, it represented the second important melos of the echos tetartos which was frequently chosen to compose new kontakia, either for the prooimion (introduction) or for the oikoi (the stanzas of the kontakion called "houses"). Usually these models were not rubrified as “avtomela”, but as idiomela which means that the modal structure of a kontakion was more complex, similar to a sticheron idiomelon changing through different echoi.

This new monastic type of kontakarion can be found in the collection of Saint Catherine's Monastery on the peninsula of Sinai (ET-MSsc Ms. Gr. 925–927) and its kontakia had only a reduced number of oikoi. The earliest kontakarion (ET-MSsc Ms. Gr. 925) dating to the 10th century might serve as an example. The manuscript was rubrified Κονδακάριον σῦν Θεῷ by the scribe, the rest is not easy to decipher since the first page was exposed to all kinds of abrasion, but it is obvious that this book is a collection of short kontakia organised according to the new menaion cycle like a sticherarion, beginning with 1 September and the feast of Symeon the Stylite. It has no notation, instead the date is indicated and the genre κονδάκιον is followed by the dedicated Saint and the incipit of the model kontakion (not even with an indication of its echos by a modal signature in this case).

Folio 2 verso shows a kontakion ἐν ἱερεῦσιν εὐσεβῶς διαπρέψας which was composed over the prooimion used for the kontakion for cross exaltation ὁ ὑψωθεῖς ἐν τῷ σταυρῷ. The prooimion is followed by three stanzas called oikoi, but they all share with the prooimion the same refrain called “ephymnion” (ἐφύμνιον) ταὶς σαῖς πρεσβεῖαις which concludes each oikos.[59] But the model for these oikoi was not taken from the same kontakion, but from the other kontakion for Theophany whose first oikos had the incipit τῇ γαλιλαίᾳ τῶν ἐθνῶν.

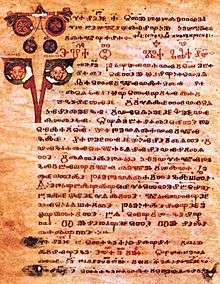

The Slavic reception

The Slavic reception is crucial for the understanding, how the kontakion has changed under the influence of the Stoudites. During the 9th and 10th centuries new Empires established in the North which were dominated by Slavic populations (mainly the first Bulgarian Empire, with two new literary centres at Preslav and the Lake Ohrid, after similar plans failed for Great Moravia, and the Kievan Rus', a federation of East Slavic tribes between the Black Sea and Scandinavia). These empires requested a state religion, legal codexes, the translation of canonic scriptures, but also the translation of an overregional liturgy as it was created by the Stoudios Monastery, Mar Saba and Saint Catherine's Monastery. The Slavic reception confirmed this new trend, but also showed a detailed interest for the cathedral rite of the Hagia Sophia and the pre-Stoudite organisation of the tropologion. Thus, these manuscripts are not only the earliest literary evidence of Slavonic languages which offer a transcription of the local variants of Slavonic languages, but also the earliest sources of the Constantinopolitan cathedral rite with musical notation, although transcribed into a notation of its own, just based on one tone system and on the contemporary layer of 11th-century notation, the roughly diastematic Old Byzantine notation.

The literary schools of the first Bulgarian empire

Unfortunately, no Slavonic tropologion written in Glagolitic script by Cyril and Methodius has survived. This lack of evidence does not prove that it had not existed, since certain conflicts with Benedictines and other Slavonic missionaries in Great Moravia and Pannonia were obviously about an Orthodox rite translated into Old Church Slavonic and practised already by Methodius and Clement of Ohrid.[60] Only few early Glagolitic sources have been left. The Kiev Missal proves a West Roman influence in the Old Slavonic liturgy for certain territories of Croatia. A later 11th-century New Testament lectionary known as the Codex Assemanius was created by the Ohrid Literary School. A euchologion (ET-MSsc Ms. Slav. 37) was in part compiled for Great Moravia by Cyril, Clement, Naum and Constantine of Preslav. It was probably copied at Preslav about the same time.[61] The aprakos lectionary proves that the Stoudites typikon was obeyed concerning the organisation of reading cycles. It explains, why Svetlana Kujumdžieva assumed that the “church order” mentioned in Methodius' vita meant the mixed Constantinopolitan Sabbaite rite established by the Stoudites. But a later finding by the same author pointed to another direction.[62] In a recent publication she chose "Iliya's book" (RUS-Mda Fond 381, Ms. 131) as the earliest example of an Old Church Slavonic tropologion (around 1100), it has compositions by Cyril of Jerusalem and agrees about 50% with the earliest tropologion of Sinai (ET-MSsc Ms. NE/MΓ 56+5) and it is likewise organised as a mеnaion (beginning with September like the Stoudites), but it still includes the movable cycle. Hence, its organisation is still close to the tropologion and it has compositions not only ascribed to Cosmas and John, but also Stephen the Sabaite, Theophanes the Branded, the Georgian scribe and hymnographer Basil at Mar Saba and Joseph the Hymnographer. Further on, musical notation has been added on some pages which reveal an exchange between Slavic literary schools and scribes of Sinai or Mar Saba:

- theta ("θ" for "thema" which indicates a melodic figure over certain syllables of the text) or fita notation was used to indicate the melodic structure of an idiomelon/samoglasen in glas 2 "Na Iordanstei rece" (Epiphany, f.109r). It was also used on other pages (kanon for hypapante, ff.118v-199r & 123r),

- two forms of znamennaya notation, an earlier one has dots on the right sight of certain signs (the kanon "Obraza drevle Moisi" in glas 8 for Cross elevation on 14 September, ff.8r-9r), and a more developed form which was obviously needed for a new translation of the text ("another" avtomelon/samopodoben, ино, glas 6 "Odesnuyu spasa" for Saint Christina of Tyre, 24 July, f.143r).[63]

.jpg)

Kujumdžieva pointed later at a Southern Slavic origin (also based on linguistic arguments since 2015), although feasts of local saints, celebrated on the same day like Christina Boris and Gleb, had been added. If its reception of a pre-Stoudite tropologion was of Southern Slavic origin, there is evidence that this manuscript was copied and adapted for a use in Northern Slavic territories. The adaption to the menaion of the Rus rather proves that notation was only used in a few parts, where a new translation of a certain text required a new melodic composition which was no longer included within the existing system of melodies established by the Stoudites and their followers. But there is a coincidence between the early fragment from the Berlin-collection, where the ἀλλὸ rubric is followed by a modal signature and some early neumes, while the elaborated zamennaya is used for a new sticheron (ино) dedicated to Saint Christina.

Recent systematic editions of the 12th-century notated miney (like RUS-Mim Ms. Sin. 162 with just about 300 folios for the month December) which included not just samoglasni (idiomela) even podobni (prosomoia) and akrosticha with notation (while the kondaks were left without notation), have revealed that the philosophy of the literary schools in Ohrid and Preslav did only require in exceptional cases the use of notation.[64] The reason is that their translation of Greek hymnography were not very literal, but often quite far from the content of the original texts, the main concern of this school was the recomposition or troping of the given system of melodies (with their models known as avtomela and heirmoi) which was left intact. The Novgorod project of re-translation during the 12th century tried to come closer to the meaning of the texts and the notation was needed to control the changes within the system of melodies.

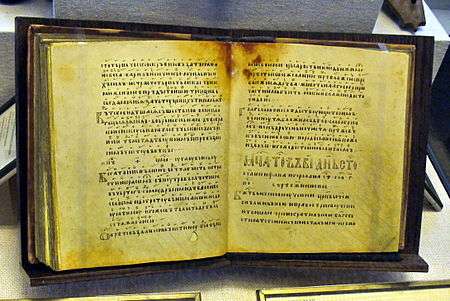

Znamennaya notation in the stichirar and the irmolog

Concerning the Slavic rite celebrated in various parts of the Kievan Rus', there was not only an interest for the organisation of monastic chant and the tropologion and the oktoich or osmoglasnik which included chant of the irmolog, podobni (prosomoia) and their models (samopodobni), but also the samoglasni (idiomela) like in case of Iliya's book.

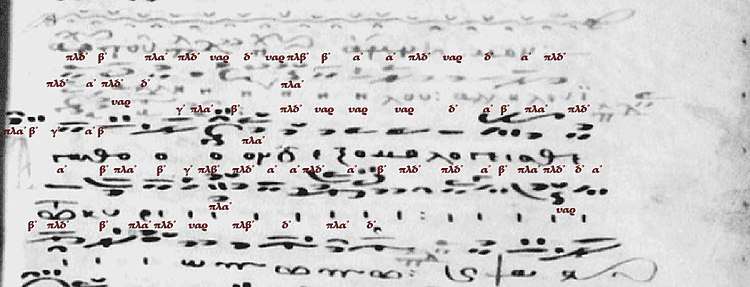

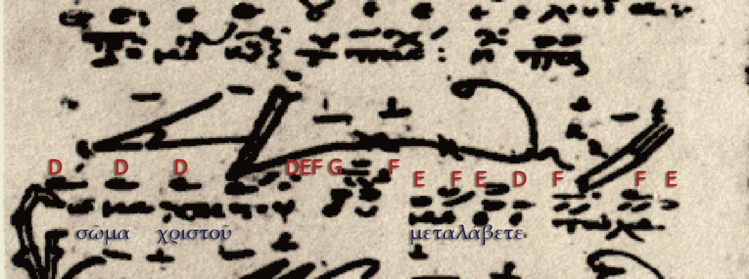

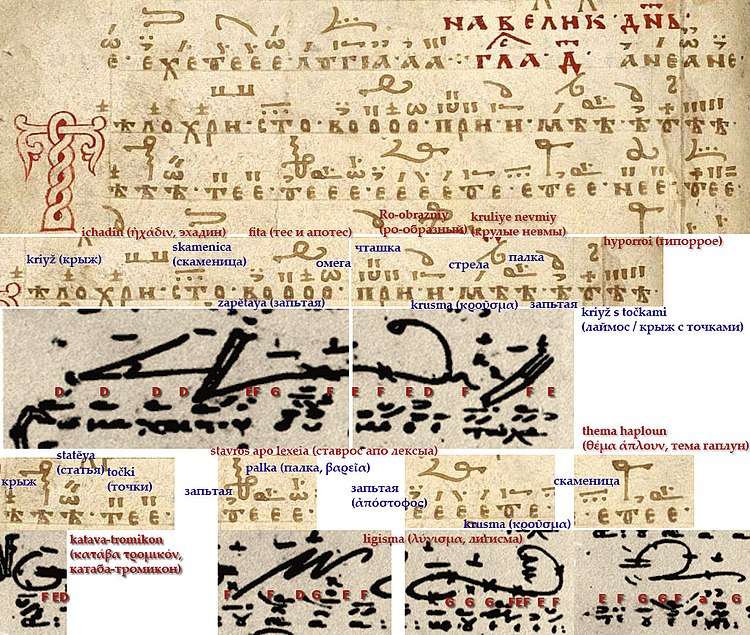

Since the 12th century, there are also Slavic stichirars which did not only include the samoglasni, but also the podobni provided with znamennaya notation. A comparison of the very first samoglasen наста въходъ лѣтоу (“Enter the entrance of the annual cycle”) in glas 1 (ἐπέστη ἡ εἴσοδος ἐνιαυτοῦ echos protos, SAV 1[65]) of the mineya shows, that the znamennaya version is much closer to fita (theta) notation, since the letter “θ =” corresponds to other signs in Coislin and a synthetic way to write a kratema group in Middle Byzantine notation. It was obviously an elaboration of the simpler version written in Coislin:

The Middle Byzantine version allows to recognise the exact steps (intervals) between the neumes. They are here described according to the Papadic practice of solfège called "parallage" (παραλλαγή) which is based on echemata: for ascending steps always kyrioi echoi are indicated, for descending steps always echemata of the plagioi echoi. If the phonic steps of the neumes were recognised according to this method, the resulting solfège was called "metrophonia". The step between the first neumes at the beginning passed through the protos pentachord between kyrios (a) and plagios phthongos (D): a—Da—a—G—a—G—FGa—a—EF—G—a—acbabcba. The Coislin version seems to end (ἐνιαυτοῦ) thus: EF—G—a—Gba (the klasma indicates that the following kolon continues immediately in the music). In znamennaya notation the combination dyo apostrophoi (dve zapĕtiye) and oxeia (strela) at the beginning (наста) is called "strela gromnaya" and obviously derived from the combination "apeso exo" in Coislin notation. According to the customs of Old Byzantine notation, "apeso exo" was not yet written with "spirits" called "chamile" and "hypsile" which did later specify as pnevmata the interval of a fifth (four steps). As usual the Old Church Slavonic translation of the text deals with less syllables than the Greek verse. The neumes only show the basic structure which was memorised as metrophonia by the use of parallage, not the melos of the performance. The melos depended on various methods to sing an idiomelon, either together with a choir or to ask a soloist to create a rather individual version (changes between soloist and choir were at least common for the period of the 14th century, when the Middle Byzantine sticherarion in this example was created). But the comparison clearly reveals the potential (δύναμις) of the rather complex genre idiomelon.

The Kievan Rus' and the earliest manuscripts of the cathedral rite

The background of Antonin's interest in celebrations at the Hagia Sophia of Constantinople, as they had been documented by his description of the ceremony around Christmas and Theophany in 1200,[66] were diplomatic exchanges between Novgorod and Constantinople.

Reception of the cathedral rite

In the Primary Chronicle (Повѣсть времѧньныхъ лѣтъ "tale of passed years") it is reported, how a legacy of the Rus’ was received in Constantinople and how they did talk about their experience in presence of Vladimir the Great in 987, before the Grand Prince Vladimir decided about the Christianization of the Kievan Rus' (Laurentian Codex written at Nizhny Novgorod in 1377):

On the morrow, the Byzantine emperor sent a message to the patriarch to inform him that a Russian delegation had arrived to examine the Greek faith, and directed him to prepare the church Hagia Sophia and the clergy, and to array himself in his sacerdotal robes, so that the Russians might behold the glory of the God of the Greeks. When the patriarch received these commands, he bade the clergy assemble, and they performed the customary rites. They burned incense, and the choirs sang hymns. The emperor accompanied the Russians to the church, and placed them in a wide space, calling their attention to the beauty of the edifice, the chanting, and the offices of the archpriest and the ministry of the deacons, while he explained to them the worship of his God. The Russians were astonished, and in their wonder praised the Greek ceremonial. Then the Emperors Basil and Constantine invited the envoys to their presence, and said, "Go hence to your native country," and thus dismissed them with valuable presents and great honor. Thus they returned to their own country, and the prince called together his vassals and the elders. Vladimir then announced the return of the envoys who had been sent out, and suggested that their report be heard. He thus commanded them to speak out before his vassals. The envoys reported: "When we journeyed among the Bulgars, we beheld how they worship in their temple, called a mosque, while they stand ungirt. The Bulgarian bows, sits down, looks hither and thither like one possessed, and there is no happiness among them, but instead only sorrow and a dreadful stench. Their religion is not good. Then we went among the Germans, and saw them performing many ceremonies in their temples; but we beheld no glory there. Then we went on to Greece, and the Greeks led us to the edifices where they worship their God, and we knew not whether we were in heaven or on earth. For on earth there is no such splendor or such beauty, and we are at a loss how to describe it. We know only that God dwells there among men, and their service is fairer than the ceremonies of other nations. For we cannot forget that beauty. Every man, after tasting something sweet, is afterward unwilling to accept that which is bitter, and therefore we cannot dwell longer here.[67]

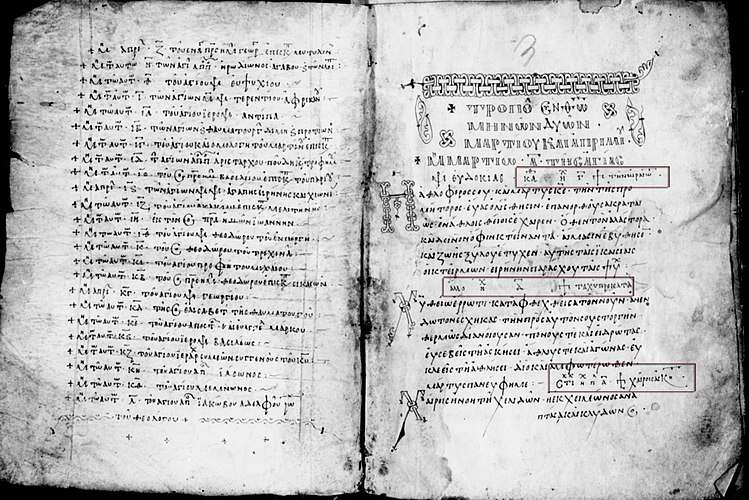

There was obviously also an interest in the representative aspect of those ceremonies at the Hagia Sophia of Constantinople. Today, it is still documented by seven Slavic kondakar's:[68]

- Tipografsky Ustav: Moscow, State Tretyakov Gallery, Ms. K-5349 (about 1100)[69]

- Two fragments of a kondakar’ (one kondak with notation): Moscow, Russian State Library (RGB), Fond 205 Ms. 107 (12th century)

- Troitsky-Lavrsky Kondakar’: Moscow, Russian State Library (RGB), Fond 304 Ms. 23 (about 1200)[70]

- Blagoveščensky Kondakar’: Saint Petersburg, National Library of Russia (RNB), Ms. Q.п.I.32 (about 1200)[71]

- Uspensky Kondakar’: Moscow, State Historical Museum (GIM), Ms. Usp. 9-п (1207, probably for the Uspensky Sobor)[72]

- Sinodal’ny Kondakar’: Moscow, State Historical Museum (GIM), Ms. Sin. 777 (early 13th century)

- South-Slavic kondakar’ without notation: Moscow, State Historical Museum (GIM), part of the Book of Prologue at the Chludov collection (14th century)

Six of them had been written in scriptoria of Kievan Rus' during the 12th and the 13th centuries, while there is one later kondakar’ without notation which was written in the Balkans during the 14th century. The aesthetic of the calligraphy and the notation has so developed over a span of 100 years that it must be regarded as a local tradition, but also one which provided us with the earliest evidence of the cheironomic signs which had only survived in one later Greek manuscript.

In 1147, the chronicler Eude de Deuil described during a visit of the Frankish King Louis VII the cheironomia, but also the presence of eunuchs during the cathedral rite. With respect to the custom of the Missa greca (for the patron of the Royal Abbey of Saint Denis), he reported that the Byzantine emperor sent his clerics to celebrate the divine liturgy for the Frankish visitors:

Novit hoc imperator; colunt etenim Graeci hoc festum, et clericorum suorum electam multitudinem, dato unicuique cereo magno, variis coloribus et auro depicto regi transmisit, et solemnitatis gloriam ampliavit. Illi quidem a nostris clericis verborum et organi genere dissidebant, sed suavi modulatione placebant. Voces enim mistae, robustior cum gracili, eunucha videlicet cum virili (erant enim eunuchi multi illorum), Francorum animos demulcebant. Gestu etiam corporis decenti et modesto, plausu manuum, et inflexione articulorum, jucunditatem visibus offerebant.[73] Since the emperor realised, that the Greeks celebrate this feast, he sent to the king a selected group of his clergy, each of whom he had equipped with a large taper [votive candle] decorated elaborately with gold and a great variety of colours; and he increased the glory of the ceremony. Those differed from our clerics concerning the words and the order of service, but they pleased us with sweet modulations. You should know that the mixed voices are more stable but with grace, the eunuchs appear with virility (for many of them were eunuchs), and softened the hearts of the Franks. Through a decent and modest gesture of the body, clapping of hands and flexions of the fingers they offered us a vision of gentleness.

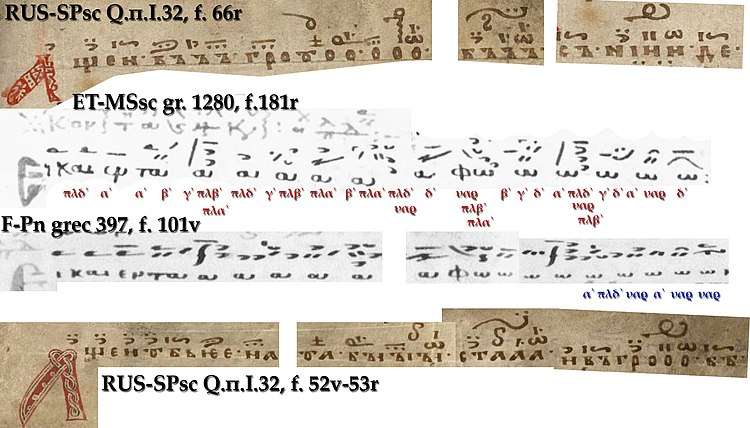

Kondakarian notation of the asmatikon part

The Kievan Rus' obviously cared about this tradition, but especially about the practice of cheironomia and its particular notation: the so-called “Kondakarian notation”.[74] A comparison with Easter koinonikon proves two things: the Slavic kondakar’ did not correspond to the “pure” form of the Greek kontakarion which was the book of the soloist who had also to recite the larger parts of the kontakia or kondaks. It was rather a mixed form which included also the choir book (asmatikon), since there is no evidence that such an asmatikon had ever been used by clerics of the Rus', while the Kondakarian notation integrated the cheironomic signs with simple signs, a Byzantine convention which had only survived in one manuscript (GR-KA Ms. 8), and combined it with Old Slavic znamennaya notation, as it had been developed in the sticheraria and heirmologia of the 12th century and the so-called Tipografsky Ustav.[75]

Although the common knowledge of znamennaya notation is as limited as the one of other Old Byzantine variants such as Coislin and Chartres notation, a comparison with the asmatikon Kastoria 8 is a kind of bridge between the former concept of cheironomiai as the only authentic notation of the cathedral rite and the hand signs used by the choir leaders and the later concept of great signs integrated and transcribed into Middle Byzantine notation, but it is a pure form of the choir book, so that such comparison is only possible for an asmatic chant genre such as the koinonikon.

See for instance the comparison of the Easter koinonikon between the Slavic Blagoveščensky kondakar’ which was written about 1200 in the Northern town Novgorod of the Rus', its name derived from its preservation at the collection of the Blagoveščensky monastery at Nizhny Novgorod.

The comparison should not suggest that both versions are identical, but the earlier source documents an earlier reception of the same tradition (since there is a difference about 120 years between both sources it is impossible to judge the differences). The rubric “Glas 4” is most likely an error of the notator and meant “Glas 5”, but it is also possible, that the Slavic tone system was already in such an early period organised in triphonia. Thus, it could also mean that анеане, undoubtly the plagios protos enechema ἀνεανὲ, was supposed to be on a very high pitch (about an octave higher), in that case the tetartos phthongos has not the octave species of tetartos (a tetrachord up and a pentachord down), but the one of plagios protos. The comparison also shows very much likeness between the use of asmatic syllables such as “оу” written as one character such as “ꙋ”. Tatiana Shvets in her description of the notational style also mentions the kola (frequent interpunction within the text line) and medial intonations can appear within a word which was sometimes due to the different numbers of syllables within the translated Slavonic text. A comparison of the neumes also show many similarities to Old Byzantine (Coislin, Chartres) signs such as ison (stolpička), apostrophos (zapĕtaya), oxeia (strela), vareia (palka), dyo kentimata (točki), dipli (statĕya), klasma (čaška), the krusma (κροῦσμα) was actually an abbreviation for a sequence of signs (palka, čaška and statĕya) and omega "ω" meant a parakalesma, a great sign related to a descending step (see the echema for plagios protos: it is combined with a dyo apostrophoi called "zapĕtaya").[76]

A melismatic polyeleos passing through 8 echoi

Another very modern part of the Blagoveščensky kondakar’ was a Polyeleos composition (a post-Stoudites custom, since they imported the Great Vesper from Jerusalem) about the psalm 135 which was divided into eight sections, each one in another glas:

- Glas 1: Ps. 135:1–4 (RUS-SPsc Ms. Q.п.I.32, f.107r).

- Glas 2: Ps. 135:5–8 (RUS-SPsc Ms. Q.п.I.32, f.107v).

- Glas 3: Ps. 135:9–12 (RUS-SPsc Ms. Q.п.I.32, f.108v).

- Glas 4: Ps. 135:13–16 (RUS-SPsc Ms. Q.п.I.32, f.109v).

- Glas 5: Ps. 135:17–20 (RUS-SPsc Ms. Q.п.I.32, f.110r).

- Glas 6: Ps. 135:21–22 (RUS-SPsc Ms. Q.п.I.32, f.110v).

- Glas 7: Ps. 135:23–24 (RUS-SPsc Ms. Q.п.I.32, f.112r).

- Glas 8: Ps. 135:25–26 (RUS-SPsc Ms. Q.п.I.32, f.113r).

The refrain алелɤгιа · алелɤгιа · ананҍанҍс · ꙗко въ вҍкы милость ѥго · алелɤгιа (“Alleluia, alleluia. medial intonation For His love endureth forever. Alleluia.”) was only written after a medial intonation for the conclusion of the first section. “Ananeanes” was the medial intonation of echos protos (glas 1).[77] This part was obviously composed without modulating to the glas of the following section. The refrain was likely sung by the right choir after the intonation of its leader: the domestikos, the preceding psalm text probably by a soloist (monophonaris) from the ambo. Interesting is that only the choir sections are entirely provided with cheironomiai. Slavic cantors had been obviously trained in Constantinople to learn the hand signs which corresponded to the great signs in the first row of Kondakarian notation, while the monophonaris parts had them only at the end, so that they were probably indicated by the domestikos or lampadarios in order to get the attention of the choir singers, before singing the medial intonations.

We do not know, whether the whole psalm was sung or each section at another day (during the Easter week, for instance, when the glas changed daily), but the following section do not have a written out refrain as a conclusion, so that the first refrain of each section was likely repeated as conclusion, often with more than one medial intonation which indicated, that there was an alternation between the two choirs. For instance within the section of glas 3 (the modal signature was obviously forgotten by the notator), where the text of the refrain is almost treated like a "nenanismaton": “але-нь-н-на-нъ-ъ-на-а-нъ-ı-ъ-лɤ-гı-а”.[78] The following medial intonations “ипе” (εἴπε “Say!”) and “пал” (παλὶν “Again!”) obviously did imitate medial intonations of the asmatikon without a true understanding of their meaning, because a παλὶν did usually indicate that something will be repeated from the very beginning. Here one choir did obviously continue another one, often interrupting it within a word.

The end of the cathedral rite in Constantinople

1207, when the Uspensky kondakar’ was written, the traditional cathedral rite had no longer survived in Constantinople, because the court and the patriarchate had gone into exile to Nikaia in 1204, after Western crusaders had made it impossible to continue the local tradition. The Greek books of the asmatikon (choir book) and the other one for the monophonaris (the psaltikon which often included the kontakarion) were written outside Constantinople, on the island of Patmos, at Saint Catherine's monastery, on the Holy Mount Athos and in Italy, in a new notation which developed some decades later within the books sticherarion and heirmologion: Middle Byzantine round notation. Thus, also the book kontakarion-psaltikon dedicated to the Constantinopolitan cathedral rite must be regarded as part of its reception history outside Constantinople like the Slavic kondakar’.

The kontakaria and asmatika written in Middle Byzantine round notation

The reason, why the psaltikon was called “kontakarion”, was that most parts of a kontakion (except of the refrain) were sung by a soloist from the ambo, and that the collection of the kontakarion had a prominent and dominant place within the book. The classical repertoire, especially the kontakion cycle of the movable feasts mainly attributed to Romanos, included usually about 60 notated kontakia which were obviously reduced to the prooimion and the first oikos and this truncated form is commonly regarded as a reason, why the notated form presented a melismatic elaboration of the kontakion as it was commonly celebrated during the cathedral rite at the Hagia Sophia. As such within the notated kontakarion-psaltikon the cycle of kontakia was combined with a prokeimenon and alleluiarion cycle as a proper chant of the divine liturgy, at least for more important feasts of the movable and immovable cycle.[79] Since the Greek kontakarion has only survived with Middle Byzantine notation which developed outside Constantinople after the decline of the cathedral rite, the notators of these books must have integrated the cheironomiai or great signs still present in the Slavic kondakar's within the musical notation of the new book sticherarion.

The typical composition of a kontakarion-psaltikon (τὸ ψαλτικὸν, τὸ κοντακάριον) was:[80]

- prokeimena

- alleluiaria

- eight hypakoai anastasimai

- kontakarion with the movable cycle integrated in the menaion after hypapante

- eight kontakia anastasima

- appendix: refrains of the alleluiaria in octoechos order, rarely alleluia endings in psalmody, or usually later added kontakia

The choral sections had been collected in a second book for the choir which was called asmatikon (τὸ ᾀσματικὸν). It contained the refrains (dochai) of the prokeimena, troparia, sometimes the ephymnia of the kontakia and the hypakoai, but also ordinary chant of the divine liturgy like the eisodikon, the trisagion, the choir sections of the cherubikon asmatikon, the weekly and annual cycle of koinonika. There were also combined forms as a kind of asmatikon-psaltikon.

In Southern Italy, there were also mixed forms of psaltikon-asmatikon which preceded the Constantinopolitan book "akolouthiai":[81]

- annual cycle of proper chant in menaion order with integrated movable cycle (kontakion with first oikos, allelouiaria, prokeimenon, and koinonikon)

- all refrains of the asmatikon (allelouiarion, psalmodic allelouiaria for polyeleoi, dochai of prokeimena, trisagion, koinonika etc.) in oktoechos order

- appendix with additions

The kontakia collection in the Greek kontakaria-psaltika

Nevertheless, the Greek monastic as well as the Slavic reception within the Kievan Rus' show many coincidences within the repertoire, so that even kontakia created in the North for local customs could be easily recognised by a comparison of Slavonic kondakar's with Greek psaltika-kontakaria. Constantin Floros’ edition of the melismatic chant proved that the total repertoire of 750 kontakia (about two thirds composed since the 10th century) was based on a very limited number of classical melodies which served as model for numerous new compositions: he counted 42 prooimia with 14 prototypes which were used as a model for other kontakia, but not rubrified as avtomela, but as idiomela (28 of them remained more or less unique), and 13 oikoi which were separately used for the recitation of oikoi. The most frequently used models also generated a prosomoion-cycle of eight kontakia anastasima.[82] The repertoire of these melodies (not so much their elaborated form) was obviously older and was transcribed by echemata in Middle Byzantine notation which were partly completely different from those used in the sticherarion. While the Hagiopolites mentioned 16 echoi of the cathedral rite (four kyrioi, four plagioi, four mesoi and four phthorai), the kontakia-idiomela alone represent at least 14 echoi (four kyrioi in devteros and tritos represented as mesos forms, four plagioi, three additional mesoi and three phthorai).

The integrative role of Middle Byzantine notation becomes visible that a lot of echemata were used which were not known from the sticherarion. Also the role of the two phthorai known as the chromatic νενανῶ and the enharmonic νανὰ was completely different from the one within the Hagiopolitan Octoechos, phthora nana clearly dominated (even in devteros echoi), while phthora nenano was rarely used. Nothing is known about the exact division of the tetrachord, because no treatise concerned with the tradition the cathedral rite of Constantinople has survived, but the Coislin sign of xeron klasma (ξηρὸν κλάσμα) appeared on different pitch classes (phthongoi) than within the stichera idiomela of the sticherarion.

The Slavic kondakar's did only use very few oikoi pointing at certain models, but the text of the first oikos was only written in the earliest manuscript known as Tipografsky Ustav, but never provided with notation.[83] If there was an oral tradition, it probably did not survive until the 13th century, because the oikoi are simply missing in the kondakar's of that period.

One example for an kondak-prosomoion whose music can be only reconstructed by a comparison with model of the kontakion as it has been notated into Middle Byzantine round notation, is Аще и убьѥна быста which was composed for the feast for Boris and Gleb (24 July) over the kondak-idiomelon Аще и въ гробъ for Easter in echos plagios tetartos:

The two Middle Byzantine versions in the kontakarion-psaltikon of Paris and the one of Sinai are not identical. The first kolon ends on different phthongoi: either on plagios tetartos (C, if the melos starts there) or one step lower on the phthongos echos varys, the plagios tritos called “grave echos” (a kind of B flat). It is definitely exaggerated to pretend that one has “deciphered” Kondakarian notation, which is hardly true for any manuscript of this period. But even considering the difference of about at least 80 years which lie between the Old Byzantine version of Slavic scribes in Novgorod (second row of the kondakar's) and the Middle Byzantine notation used by the monastic scribes of the later Greek manuscripts, it seems obvious that all three manuscripts in comparison did mean one and the same cultural heritage associated with the cathedral rite of the Hagia Sophia: the melismatic elaboration of the truncated kontakion. Both Slavonic kondaks follow strictly the melismatic structure in the music and the frequent segmentation by kola (which does not exist in the Middle Byzantine version), interrupting the conclusion of the first text unit by an own kolon using with the asmatic syllable “ɤ”.

Concerning the two martyre princes of the Kievan Rus’ Boris and Gleb, there are two kondak-prosomoia dedicated to them in the Blagoveščensky Kondakar’ on the folios 52r–53v: the second is the prosomoion over the kondak-idiomelon for Easter in glas 8, the first the prosomoion Въси дьньсь made over the kondak-idiomelon for Christmas Дева дньсь (Ἡ παρθένος σήμερον) in glas 3.[84] Unlike the Christmas kontakion in glas 3, the Easter kontakion was not chosen as model for the kontakion anastasimon of glas 8 (plagios tetartos). It had two other important rivals: the kontakion-idiomelon Ὡς ἀπαρχάς τῆς φύσεως (ꙗко начатъкы родоу) for All Saints, although an enaphonon (protos phthongos) which begins on the lower fourth (plagios devteros), and the prooimion Τῇ ὑπερμάχῳ στρατιγῷ (Възбраньноумоу воѥводѣ побѣдьнаꙗ) of the Akathistos hymn in echos plagios tetartos (which only appears in Greek kontakaria-psaltika).

Even among the notated sources there was a distinction between the short and the long psaltikon style which was based on the musical setting of the kontakia, established by Christian Thodberg and by Jørgen Raasted. The latter chose Romanos’ Christmas kontakion Ἡ παρθένος σήμερον to demonstrate the difference and his conclusion was that the known Slavic kondakar's did rather belong to the long psaltikon style.[85]

The era of psaltic art and the new mixed rite of Constantinople

There was a discussion promoted by Christian Troelsgård that Middle Byzantine notation should not be distinguished from Late Byzantine notation.[86] The argument was that the establishment of a mixed rite after the return of the court and the patriarchate from the exile in Nikaia in 1261, had nothing really innovative with respect the sign repertoire of Middle Byzantine notation. The innovation was probably already done outside Constantinople, in those monastic scriptoria whose scribes cared about the lost cathedral rite and did integrate different forms of Old Byzantine notation (those of the sticherarion and heirmologion like theta notation, Coislin and Chartres type as well as those of the Byzantine asmatikon and kontakarion which were based on cheironomies). The argument was mainly based on the astonishing continuity that a new a type of treatise revealed by its continuous presence from the 13th to the 19th centuries: the Papadike. In a critical edition of this huge corpus, Troelsgård together with Maria Alexandru discovered many different functions that this treatise type could have.[87] It was originally an introduction for a revised type of sticherarion, but it also introduced many other books like mathemataria (literally “a book of exercises” like a sticherarion kalophonikon or a book with heirmoi kalophonikoi, stichera kalophonika, anagrammatismoi and kratemata), akolouthiai (from “taxis ton akolouthion” which meant “order of services”, a book which combined the choir book “asmatikon”, the book of the soloist “kontakarion”, and with the rubrics the instructions of the typikon) and the Ottoman anthologies of the Papadike which tried to continue the tradition of the notated book akolouthiai (usually introduced by a Papadike, a kekragarion/anastasimatarion, an anthology for Orthros, and an anthology for the divine liturgies).