Kontakion

The kontakion (Greek: κοντάκιον, also transliterated as kondakion and kontakio; plural Greek: κοντάκια, kontakia) is a form of hymn performed in the Orthodox and the Eastern Catholic liturgical traditions. The kontakion originated in the Byzantine Empire around the sixth century CE. It is divided into strophes (oikoi, stanzas) and begins with a prologue (the prooimoion or koukoulion). The kontakion usually has a biblical theme, and often features dialogue between biblical characters. By far the most important writer of kontakia is Romanos the Melodist. The only kontakion that is regularly performed in full today is the Akathist to the Theotokos.

Etymology

The word 'kontakion' derives from the Greek κόνταξ (kontax), which means 'rod' or 'stick' and refers specifically to the pole around which a scroll is wound.[1] The term describes the way in which the words on a scroll unfurl as it is read. The word was originally used to describe an early Byzantine poetic form, whose origins date back certainly as far as the sixth century CE, and possibly earlier. Nevertheless, the term itself is of ninth-century origin.[2]

There is also a chant book named after the hymn genre kontakion, the kontakarion (Greek: κοντακάριον) or kondakar (Church Slavonic: Кондакар). The kontakarion is not just a collection of kontakia: within the tradition of the Cathedral Rite (like the rite practiced at the Hagia Sophia of Constantinople) it became the name of the book of the prechanter or lampadarios, also known as "psaltikon", which contained all the soloistic parts of hymns sung during the morning service and the Divine Liturgy. Because the kontakia were usually sung by protopsaltes during the morning services, the first part for the morning service with its prokeimena and kontakia was the most voluminous part, so it was simply called kontakarion.

History

Originally the kontakion was a Syriac form of poetry which became popular in Constantinople under Romanos the Melodist, Anastasios and Kyriakos during the 6th century and was continued by Sergius I of Constantinople and Sophronius of Jerusalem during the 7th century. Romanos' works had been widely acknowledged as a crucial contribution to Byzantine hymnography, in some kontakia he did also support Emperor Justinian by writing state propaganda.[3]

Romanos' kontakion On the Nativity of Christ was also mentioned in his vita. Until the twelfth century, it was sung every year at the imperial banquet on that feast by the joint choirs of Hagia Sophia and of the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople. Most of the poem takes the form of a dialogue between the Mother of God and the Magi.[4]

A kontakion is a poetic form frequently encountered in Byzantine hymnography. It was probably based on Syriac hymnographical traditions, which were transformed and developed in Greek-speaking Byzantium. It was a homiletic genre and could be best described as a "sermon in verse accompanied by music". In character it is similar to the early Byzantine festival sermons in prose — a genre developed by Ephrem the Syrian — but meter and music have greatly heightened the drama and rhetorical beauty of the speaker’s often profound and very rich meditation.

Medieval manuscripts preserved about 750 kontakia since the 9th century, about two thirds had been composed since the 10th century, but they were rather liturgical compositions with about two or six oikoi, each one concluded by a refrain identical to the introduction (prooimion). Longer compositions were the Slavic Akafist which were inspired by an acrostic kontakion whose 24 stanzas started with each letter of the alphabet (Akathist).

Within the cathedral rite developed a truncated which reduced the kontakion to one oikos or just to the prooimion, while the music was elaborated to a melismatic style. The classical repertoire consisted of 42 kontakia-idiomela, and 44 kontakia-prosomoia made about a limited number of model stanzas consisting of fourteen prooimia-idiomela and thirteen okoi-idiomela which could be combined independently.[5] This classical repertoire was dominated by classical composers of the 6th and 7th centuries.

Form

The form generally consists of 18 to 24 metrically identical stanzas called oikoi (“houses”), preceded, in a different meter, by a short prelude, called a koukoulion (cowl) or prooimoion. The first letters of each of the stanzas form an acrostic, which frequently includes the name of the poet. For example, Romanos' poems often include the acrostic "Of the Humble Romanos" or "The Poem of the Humble Romanos".[2] The last line of the prelude introduces a refrain called “ephymnion”, which is repeated at the end of all the stanzas.

The main body of a kontakion was chanted from the ambo by a cleric (often a deacon; otherwise a reader) after the reading of the Gospel, while a choir, or even the whole congregation, joined in the refrain. The length of many kontakia — indeed, the epic character of some — suggest that the majority of the text must have been delivered in a kind of recitative, but unfortunately, the original music which accompanied the kontakia has now been lost.[6]

The liturgical place of the kontakion

Within the cathedral rite, the ritual context of the long kontakion was the pannychis during solemn occasions (a festive night vigil) and was usually celebrated at the Blachernae Chapel.[7] Assumptions that kontakia replaced canon poetry or vice versa that the Stoudites replaced the kontakia with Hagiopolitan canon poetry, always remained controversial. The Patriarch Germanus I of Constantinople established an own local school earlier (even if it is no longer present in the modern books), while the Stoudites embraced the genre kontakion with own new compositions. The only explanation is that different customs must have existed simultaneously, the truncated and the long kontakion, but also the ritual context of both customs.

The truncated form consisted only of the first stanza called "koukoulion" (now referred to as "the kontakion") and the first oikos, while the other oikoi became omitted. Within the Orthros for the kontakion and oikos is after the sixth ode of the canon; however, if the typikon for the day calls for more than one kontakion at matins, the kontakion and oikos of the more significant feast is sung after the sixth ode, while those of the less significant feast are transferred to the place following the third ode, before the kathismata.[8][9]

Since the late 13th century, when the Court and the Patriarchate returned from exile in Nikaia, the former cathedral rite was not continued and thus, also the former celebration of kontakion changed. The only entire kontakion celebrated was the Akathist hymn. Its original place was within the menaion the feast of Annunciation (25 March). In later kontakaria and oikemataria which treated all 24 oikoi in a kalophonic way, the Akathist was written as part of the triodion, within the oikematarion the complete kontakion filled half the volume of the whole book.[10] As such it could only be performed in short sections throughout Great Lent and became a kind of para-liturgical genre. In the modern practice it is reduced to heirmologic melos which allowed the celebration of the whole Akathist on the morning service of the fourth Sunday of Great Lent.[11][12] This Akathist was traditionally ascribed to Romanos, but recent scholarship has disapproved it. In Slavic hymnography the so-called Akafist became a genre of its own which was dedicated to various saints; while not part of any prescribed service, these may be prayed as a devotional hymn at any time.

The current practice treats the kontakion as a proper troparion, based on the text of the prooimion, dedicated to a particular feast of the menaion or the moveable cycle.

Prooimia of 4 classical kontakia

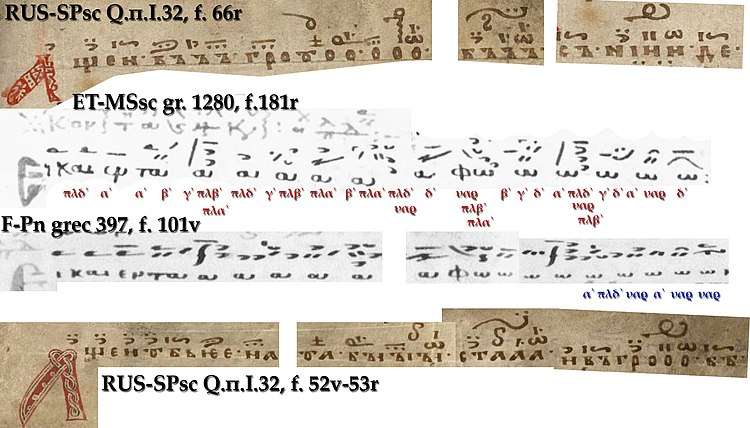

The examples chosen here are only the introduction (prooimion, koukoulion) and they belong to the old core repertoire of 86 kontakia which had been all known as part of the cathedral rite. Thus, they can be found with notation in the kontakarion-psaltikon.[5]

According to the melodic system of the cathedral rite, certain kontakia-idiomela served as melodic models which had been used to compose other kontakia. The kontakion for Easter for instance was used to compose an Old Church Slavonic kondak in honour of the local saints Boris and Gleb, two martyre princes of the Kievan Rus. The concluding verse called “ephymnion” (ἐφύμνιον) was repeated like a refrain after each oikos and its melody was used in all kontakia composed in the echos plagios tetartos.

Kontakion of Pascha (Easter)

The Slavic kondakar has the old gestic notation which referred (in the first row) to the hand signs used by the choirleaders to coordinate the singers. Except for the ephymnion the whole prooimion and the oikoi were recited by a soloist called "monophonaris" (the hand sign were not so important than during the ephymnion). The Middle Byzantine notation used in the Greek kontakarion-psaltikon rather showed the melismatic melos behind these signs.

Εἰ καὶ ἐν τάφῳ κατῆλθες ἀθάνατε,

ἀλλὰ τοῦ ᾍδου καθεῖλες

τὴν δύναμιν, καὶ ἀνέστης ὡς νικητής, Χριστὲ ὁ Θεός,

γυναιξὶ Μυροφόροις φθεγξάμενος.

Χαίρετε, καὶ τοῖς σοῖς Ἀποστόλοις εἰρήνην

δωρούμενος ὁ τοῖς πεσοῦσι παρέχων ἀνάστασιν.

Аще и въ гробъ съниде бесъмьртьне

нъ адѹ раздрѹши силѹ

и въскрьсе ꙗко побѣдителъ христе боже

женамъ мюроносицѧмъ радость провѣща

и своимъ апостолѡмъ миръ дарова

падъшимъ подаꙗ въскрьсениѥ[13]

Though Thou didst descend into the grave, O Immortal One,

yet didst Thou destroy the power of Hades,

and didst arise as victory, O Christ God,

calling to the myrrh-bearing women:

Rejoice! and giving peace unto Thine apostles,

Thou Who dost grant resurrection to the fallen.[14]

Another example composed in the same echos is the Akathist hymn, originally provided for the feast of Annunciation (nine months before Nativity).

Kontakion of the Annunciation of the Most Holy Theotokos (25 March)

Τῇ ὑπερμάχῳ στρατηγῷ τὰ νικητήρια,

ὡς λυτρωθεῖσα τῶν δεινῶν εὐχαριστήρια,

ἀναγράφω σοι ἡ πόλις σου, Θεοτόκε·

ἀλλʹ ὡς ἔχουσα τὸ κράτος προσμάχητον,

ἐκ παντοίων με κινδύνων ἐλευθέρωσον, ἵνα κράζω σοί∙

Χαῖρε Νύμφη ἀνύμφευτε.

Възбраньнѹмѹ воѥводѣ побѣдьнаꙗ

ꙗко избывъ ѿ зълъ благодарениꙗ

въсписаѥть ти градъ твои богородице

нъ ꙗко имѹщи дьржавѹ непобѣдимѹ

ѿ вьсѣхъ мѧ бѣдъ свободи и да зовѹ ти

радѹи сѧ невѣсто неневѣстьнаꙗ.[15]

To thee, the Champion Leader,

we thy servants dedicate a feast of victory

and of thanksgiving as ones rescued out of sufferings, O Theotokos;

but as thou art one with might which is invincible,

from all dangers that can be do thou deliver us, that we may cry to thee:

Rejoice, thou Bride Unwedded.[14]

Kontakion of the Transfiguration of the Lord (6 August)

This kontakion-idiomelon by Romanos the Melodist was composed in echos varys (the grave mode) and the prooimion was chosen as model for the prosomoion of the resurrection kontakion Ἐκ τῶν τοῦ ᾍδου πυλῶν in the same echos.

Ἐπὶ τοῦ ὄρους μετεμορφώθης,

καὶ ὡς ἐχώρουν οἱ Μαθηταί σου,

τὴν δόξαν σου Χριστὲ ὁ Θεὸς ἐθεάσαντο·

ἵνα ὅταν σὲ ἴδωσι σταυρούμενον,

τὸ μὲν πάθος νοήσωσιν ἑκούσιον,

τῷ δὲ κόσμω κηρύξωσιν,

ὅτι σὺ ὑπάρχεις ἀληθῶς, τοῦ Πατρὸς τὸ ἀπαύγασμα.

На горѣ прѣобрази сѧ

и ꙗко въмѣщахѹ ѹченици твои

славѹ твою христе боже видѣша

да ѥгда тѧ ѹзьрѧть распинаѥма

страсть ѹбо разѹмѣють вольнѹю

мирѹ же провѣдѧть

ꙗко ты ѥси въ истинѹ отьче сиꙗниѥ[16]

On the mount Thou was (sic) transfigured,

and Thy disciples, as much as they could bear,

beheld Thy glory, O Christ God;

so that when they should see Thee crucified,

they would know Thy passion to be willing,

and would preach to the world

that Thou, in truth, art the Effulgence of the Father.[14]

Kontakion of the Sunday of the Prodigal Son (9th week before Easter, 2nd week of the triodion)

The last example is not a model, but a kontakion-prosomoion which had been composed over the melody of Romanos the Melodist's Nativity kontakion Ἡ παρθένος σήμερον in echos tritos.[17]

Τῆς πατρῴας, δόξης σου, ἀποσκιρτήσας ἀφρόνως,

ἐν κακοῖς ἐσκόρπισα, ὅν μοι παρέδωκας πλοῦτον·

ὅθεν σοι τὴν τοῦ Ἀσώτου, φωνὴν κραυγάζω·

Ἥμαρτον ἐνώπιόν σου Πάτερ οἰκτίρμον,

δέξαι με μετανοοῦντα, καὶ ποίησόν με, ὡς ἕνα τῶν μισθίων σου.

Having foolishly abandoned Thy paternal glory,

I squandered on vices the wealth which Thou gavest me.

Wherefore, I cry unto Thee with the voice of the Prodigal:

I have sinned before Thee, O compassionate Father.

Receive me as one repentant, and make me as one of Thy hired servants.[14]

Notes

- Mpampiniotis, Georgios (1998). Lexiko tis neas ellinikis glossas (Dictionary of the Modern Greek Language — in Greek). Athens: Kentro lexikologias.

- Gador-Whyte, Sarah (2017). Theology and poetry in early Byzantium: the Kontakia of Romanos the Melodist. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 9–11. ISBN 9781316492512. OCLC 992462921.

- Concerning the inauguration of the Hagia Sophia, see Johannes Koder (2008).

- The Magis' visit to the newborn Child is celebrated in the Orthodox Church on 25 December rather than on 6 January (the Feast of the Theophany on 6 January celebrates the Baptism of Christ in the Orthodox Church).

- See the edition by Constantin Floros (2015).

- Lash, Archimandrite Ephrem (1995). St. Romanos the Melodist, On the Life of Christ: Kontakia. San Francisco: Harper. pp. 1–12.

- Alexander Lingas (1995).

- Liturgics Archived 2011-07-26 at the Wayback Machine, section "The Singing of the Troparia and Kontakia", Retrieved 2012-01-17

- Тvпико́нъ, p 7, 11, 12, etc.

- See the Oikematarion written at Mone Esphigmenou (ET-MSsc Ms. Sin. gr. 1262, ff.67v-131r).

- Liturgics Archived 2011-07-26 at the Wayback Machine, section "The Fourth Sunday of Lent", Retrieved 2012-01-17

- Тvпико́нъ, p 437

- Quoted according to the Blagoveščensky kondakar’ (RUS-SPsc Ms. Q.п.I.32, f. 66).

- Translation according to the Prayer Book published by Holy Trinity Monastery (Jordanville, New York).

- Quoted according to the Blagoveščensky kondakar’ (RUS-SPsc Ms. Q.п.I.32, f. 36v-37r).

- Quoted according to the Tipografsky Ustav (RUS-Mgt Ms. K-5349, f.75v-76r). Edition by Boris Uspenskiy (2006).

- For other kontakia-prosomoia of the same model, see the article idiomelon.

References

- Archbishop Averky († 1976); Archbishop Laurus (2000). "Liturgics". Holy Trinity Orthodox School, Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, 466 Foothill Blvd, Box 397, La Canada, California 91011, USA. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- Тvпико́нъ сіесть уста́въ (Title here transliterated into Russian; actually in Church Slavonic) (The Typicon which is the Order), Москва (Moscow, Russian Empire): Сvнодальная тvпографiя (The Synodal Printing House), 1907

- Floros, Constantin (2015). Das mittelbyzantinische Kontaktienrepertoire. Untersuchungen und kritische Edition. 1–3. Hamburg (Habilitation 1961 at University of Hamburg).CS1 maint: location (link)

- Floros, Constantin; Neil K. Moran (2009). The Origins of Russian Music - Introduction to the Kondakarian Notation. Frankfurt, M. [u.a.]: Lang. ISBN 978-3-631-59553-4.

- Koder, Johannes (2008). "Imperial Propaganda in the Kontakia of Romanos the Melode". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 62: 275–291, 281. ISSN 0070-7546. JSTOR 20788050.

- Lingas, Alexander (1995). "The Liturgical Place of the Kontakion in Constantinople". In Akentiev, Constantin C. (ed.). Liturgy, Architecture and Art of the Byzantine World: Papers of the XVIII International Byzantine Congress (Moscow, 8–15 August 1991) and Other Essays Dedicated to the Memory of Fr. John Meyendorff. Byzantino Rossica. 1. St. Petersburg. pp. 50–57.

Sources

- "Sinai, Saint Catherine's Monastery, Ms. Gr. 925". Kontakarion organised as a menaion, triodion (at least in part), and pentekostarion (10th century).

- "Saint-Petersburg, Rossiyskaya natsional'naya biblioteka, Ms. Q.п.I.32". Nižegorodsky Kondakar' of the Blagoveščensky [Annunciation] Monastery, introduced, described and transcribed by Tatiana Shvets (about 1200).

- "Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, fonds. grec, Ms. 397". Incomplete Kontakarion (Prokeimena, Stichologia for Christmas and Theophany, Allelouiaria, Hypakoai anastasima, kontakia) in short psaltikon style with Middle Byzantine Round notation (late 13th c.).

- "Sinai, Saint Catherine's Monastery, Ms. Gr. 1280". Psaltikon (Prokeimena, Allelouiaria, Hypakoai, Anti-cherouvikon for the Liturgy of Presanctified Gifts) and Kontakarion (menaion with integrated movable cycle) with Middle Byzantine round notation written in a monastic context (about 1300).

- "Sinai, Saint Catherine's Monastery, Ms. Gr. 1314". Psaltikon-Kontakarion (prokeimena, allelouiaria, kontakarion with integrated hypakoai, hypakoai anastasima, the complete Akathistos hymn, kontakia anastasima, stichera heothina, appendix with refrains of the allelouiaria in oktoechos order) written by monk Neophyte (mid 14th century).

- "Sinai, Saint Catherine's Monastery, Ms. Gr. 1262". Oikematarion kalophonikon based on papadic compositions by Michael Aneotos and kalopismoi by Ioannis Glykys copied by Gregorios Monachos at the Mone Esphigmenou on the Holy Mount Athos (1437).

Editions

- Uspenskiy, Boris Aleksandrovič, ed. (2006). Типографский Устав: Устав с кондакарем конца XI — начала XII века [Tipografsky Ustav: Ustav with Kondakar' end 11th-beginning 12th c. (vol. 1: facsimile, vol. 2: edition of the texts, vol. 3: monographic essays)]. Памятники славяно-русской письменности. Новая серия. 1–3. Moscow: Языки славянских культур. ISBN 978-5-9551-0131-6.