Prometheus

In Greek mythology, Prometheus (/prəˈmiːθiəs/; Ancient Greek: Προμηθεύς, [promɛːtʰéu̯s], possibly meaning "forethought")[1] is a culture hero, and trickster figure who is credited with the creation of humanity from clay, and who defies the gods by stealing fire and giving it to humanity as civilization. Prometheus is known for his intelligence and as a champion of humankind[2] and also seen as the author of the human arts and sciences generally. He is sometimes presented as the father of Deucalion, the hero of the flood story.

| Prometheus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Iapetus and Asia or Clymene |

| Siblings | Atlas, Epimetheus, Menoetius, Anchiale |

The punishment of Prometheus as a consequence of the theft of fire is a popular subject of both ancient and modern culture. Zeus, king of the Olympian gods, sentenced the Titan to eternal torment for his transgression. The immortal was bound to a rock, where each day an eagle, the emblem of Zeus, was sent to eat Prometheus' liver, which would then grow back overnight to be eaten again the next day (in ancient Greece, the liver was often thought to be the seat of human emotions).[3][4] Prometheus was eventually freed by the hero Heracles.

In another myth, Prometheus establishes the form of animal sacrifice practiced in ancient Greek religion.

Evidence of a cult to Prometheus himself is not widespread. He was a focus of religious activity mainly at Athens, where he was linked to Athena and Hephaestus, other Greek deities of creative skills and technology.[5]

In the Western classical tradition, Prometheus became a figure who represented human striving, particularly the quest for scientific knowledge, and the risk of overreaching or unintended consequences. In particular, he was regarded in the Romantic era as embodying the lone genius whose efforts to improve human existence could also result in tragedy: Mary Shelley, for instance, gave The Modern Prometheus as the subtitle to her novel Frankenstein (1818).

Etymology

The etymology of the theonym prometheus is debated. The classical view is that it signifies "forethought," as that of his brother Epimetheus denotes "afterthought".[6] Hesychius of Alexandria gives Prometheus the variant name of Ithas, and adds "whom others call Ithax", and describes him as the Herald of the Titans.[7] Kerényi remarks that these names are "not transparent", and may be different readings of the same name, while the name "Prometheus" is descriptive.[8]

It has also been theorised that it derives from the Proto-Indo-European root that also produces the Vedic pra math, "to steal", hence pramathyu-s, "thief", cognate with "Prometheus", the thief of fire. The Vedic myth of fire's theft by Mātariśvan is an analogue to the Greek account.[9] Pramantha was the fire-drill, the tool used to create fire.[10] The suggestion that Prometheus was in origin the human "inventor of the fire-sticks, from which fire is kindled" goes back to Diodorus Siculus in the first century BC. The reference is again to the "fire-drill", a worldwide primitive method of fire making using a vertical and a horizontal piece of wood to produce fire by friction.[11]

Myths and legends

Possible sources

The oldest record of Prometheus is in Hesiod, but stories of theft of fire by a trickster figure are widespread around the world. Some other aspects of the story resemble the Sumerian myth of Enki (or Ea in later Babylonian mythology), who was also a bringer of civilisation who protected humanity against the other gods.[12] That Prometheus descends from the Vedic fire bringer Mātariśvan was suggested in the 19th century, lost favour in the 20th century, but is still supported by some.[13]

Oldest legends

Hesiod's Theogony and Works of the Days

Theogony

The first recorded account of the Prometheus myth appeared in the late 8th-century BC Greek epic poet Hesiod's Theogony (507–616). He was a son of the Titan Iapetus by Clymene, one of the Oceanids. He was brother to Menoetius, Atlas, and Epimetheus. Hesiod, in Theogony, introduces Prometheus as a lowly challenger to Zeus's omniscience and omnipotence.

In the trick at Mecone (535–544), a sacrificial meal marking the "settling of accounts" between mortals and immortals, Prometheus played a trick against Zeus. He placed two sacrificial offerings before the Olympian: a selection of beef hidden inside an ox's stomach (nourishment hidden inside a displeasing exterior), and the bull's bones wrapped completely in "glistening fat" (something inedible hidden inside a pleasing exterior). Zeus chose the latter, setting a precedent for future sacrifices (556–557). Henceforth, humans would keep that meat for themselves and burn the bones wrapped in fat as an offering to the gods. This angered Zeus, who hid fire from humans in retribution. In this version of the myth, the use of fire was already known to humans, but withdrawn by Zeus.[14]

Prometheus stole fire back from Zeus in a giant fennel-stalk and restored it to humanity (565–566). This further enraged Zeus, who sent the first woman to live with humanity (Pandora, not explicitly mentioned). The woman, a "shy maiden", was fashioned by Hephaestus out of clay and Athena helped to adorn her properly (571–574). Hesiod writes, "From her is the race of women and female kind: of her is the deadly race and tribe of women who live amongst mortal men to their great trouble, no helpmeets in hateful poverty, but only in wealth" (590–594). For his crimes, Prometheus is punished by Zeus who bound him with chains, and sent an eagle to eat Prometheus' immortal liver every day, which then grew back every night. Years later, the Greek hero Heracles, with Zeus' permission, killed the eagle and freed Prometheus from this torment (521–529).

Works and Days

Hesiod revisits the story of Prometheus and the theft of fire in Works and Days (42–105). In it the poet expands upon Zeus's reaction to Prometheus' deception. Not only does Zeus withhold fire from humanity, but "the means of life" as well (42). Had Prometheus not provoked Zeus's wrath, "you would easily do work enough in a day to supply you for a full year even without working; soon would you put away your rudder over the smoke, and the fields worked by ox and sturdy mule would run to waste" (44–47).

Hesiod also adds more information to Theogony's story of the first woman, a maiden crafted from earth and water by Hephaestus now explicitly called Pandora ("all gifts") (82). Zeus in this case gets the help of Athena, Aphrodite, Hermes, the Graces and the Hours (59–76). After Prometheus steals the fire, Zeus sends Pandora in retaliation. Despite Prometheus' warning, Epimetheus accepts this "gift" from the gods (89). Pandora carried a jar with her from which were released mischief and sorrow, plague and diseases (94–100). Pandora shuts the lid of the jar too late to contain all the evil plights that escaped, but Hope is left trapped in the jar because Zeus forces Pandora to seal it up before Hope can escape (96–99).

Interpretation

Angelo Casanova,[15] professor of Greek literature at the University of Florence, finds in Prometheus a reflection of an ancient, pre-Hesiodic trickster-figure, who served to account for the mixture of good and bad in human life, and whose fashioning of humanity from clay was an Eastern motif familiar in Enuma Elish. As an opponent of Zeus he was an analogue of the Titans and, like them, was punished. As an advocate for humanity he gains semi-divine status at Athens, where the episode in Theogony in which he is liberated[16] is interpreted by Casanova as a post-Hesiodic interpolation.[17]

According to the German classicist Karl-Martin Dietz, in Hesiod's scriptures, Prometheus represents the "descent of mankind from the communion with the gods into the present troublesome life".[18]

The Lost Titanomachy

The Titanomachy is a lost epic of the cosmological struggle between the Greek gods and their parents, the Titans, and is a probable source of the Prometheus myth.[19] along with the works of Hesiod. Its reputed author was anciently supposed to have lived in the 8th century BC, but M. L. West has argued that it can't be earlier than the late 7th century BC.[20] Presumably included in the Titanomachy is the story of Prometheus, himself a Titan, who managed to avoid being in the direct confrontational cosmic battle between Zeus and the other Olympians against Cronus and the other Titans[21] (although there is no direct evidence of Prometheus' inclusion in the epic).[22] M. L. West notes that surviving references suggest that there may have been significant differences between the Titanomachy epic and the account of events in Hesiod; and that the Titanomachy may be the source of later variants of the Prometheus myth not found in Hesiod, notably the non-Hesiodic material found in the Prometheus Bound of Aeschylus.[23]

Athenian tradition

The two major authors to have an influence on the development of the myths and legends surrounding the Titan Prometheus during the Socratic era of greater Athens were Aeschylus and Plato. The two men wrote in highly distinctive forms of expression which for Aeschylus centered on his mastery of the literary form of Greek tragedy, while for Plato this centered on the philosophical expression of his thought in the form of the various dialogues he wrote or recorded during his lifetime.

Aeschylus and the ancient literary tradition

Prometheus Bound, perhaps the most famous treatment of the myth to be found among the Greek tragedies, is traditionally attributed to the 5th-century BC Greek tragedian Aeschylus.[24] At the centre of the drama are the results of Prometheus' theft of fire and his current punishment by Zeus. The playwright's dependence on the Hesiodic source material is clear, though Prometheus Bound also includes a number of changes to the received tradition.[25] It has been suggested by M.L. West that these changes may derive from the now lost epic Titanomachy[26]

Before his theft of fire, Prometheus played a decisive role in the Titanomachy, securing victory for Zeus and the other Olympians. Zeus' torture of Prometheus thus becomes a particularly harsh betrayal. The scope and character of Prometheus' transgressions against Zeus are also widened. In addition to giving humanity fire, Prometheus claims to have taught them the arts of civilisation, such as writing, mathematics, agriculture, medicine, and science. The Titan's greatest benefaction for humanity seems to have been saving them from complete destruction. In an apparent twist on the myth of the so-called Five Ages of Man found in Hesiod's Works and Days (wherein Cronus and, later, Zeus created and destroyed five successive races of humanity), Prometheus asserts that Zeus had wanted to obliterate the human race, but that he somehow stopped him.

Moreover, Aeschylus anachronistically and artificially injects Io, another victim of Zeus's violence and ancestor of Heracles, into Prometheus' story. Finally, just as Aeschylus gave Prometheus a key role in bringing Zeus to power, he also attributed to him secret knowledge that could lead to Zeus's downfall: Prometheus had been told by his mother Themis, who in the play is identified with Gaia (Earth), of a potential marriage that would produce a son who would overthrow Zeus. Fragmentary evidence indicates that Heracles, as in Hesiod, frees the Titan in the trilogy's second play, Prometheus Unbound. It is apparently not until Prometheus reveals this secret of Zeus's potential downfall that the two reconcile in the final play, Prometheus the Fire-Bringer or Prometheus Pyrphoros, a lost tragedy by Aeschylus.

Prometheus Bound also includes two mythic innovations of omission. The first is the absence of Pandora's story in connection with Prometheus' own. Instead, Aeschylus includes this one oblique allusion to Pandora and her jar that contained Hope (252): "[Prometheus] caused blind hopes to live in the hearts of men." Second, Aeschylus makes no mention of the sacrifice-trick played against Zeus in the Theogony.[24] The four tragedies of Prometheus attributed to Aeschylus, most of which are lost to the passages of time into antiquity, are Prometheus Bound (Prometheus Desmotes), Prometheus Unbound (Lyomenos), Prometheus the Fire Bringer (Pyrphoros), and Prometheus the Fire Kindler (Pyrkaeus).

The larger scope of Aeschylus as a dramatist revisiting the myth of Prometheus in the age of Athenian prominence has been discussed by William Lynch.[27] Lynch's general thesis concerns the rise of humanist and secular tendencies in Athenian culture and society which required the growth and expansion of the mythological and religious tradition as acquired from the most ancient sources of the myth stemming from Hesiod. For Lynch, modern scholarship is hampered by not having the full trilogy of Prometheus by Aeschylus, the last two parts of which have been lost to antiquity. Significantly, Lynch further comments that although the Prometheus trilogy is not available, that the Orestia trilogy by Aeschylus remains available and may be assumed to provide significant insight into the overall structural intentions which may be ascribed to the Prometheus trilogy by Aeschylus as an author of significant consistency and exemplary dramatic erudition.[28]

Harold Bloom, in his research guide for Aeschylus, has summarised some of the critical attention that has been applied to Aeschylus concerning his general philosophical import in Athens.[29] As Bloom states, "Much critical attention has been paid to the question of theodicy in Aeschylus. For generations, scholars warred incessantly over 'the justice of Zeus,' unintentionally blurring it with a monotheism imported from Judeo-Christian thought. The playwright undoubtedly had religious concerns; for instance, Jacqueline de Romilly[30] suggests that his treatment of time flows directly out of his belief in divine justice. But it would be an error to think of Aeschylus as sermonising. His Zeus does not arrive at decisions which he then enacts in the mortal world; rather, human events are themselves an enactment of divine will."[31]

According to Thomas Rosenmeyer, regarding the religious import of Aeschylus, "In Aeschylus, as in Homer, the two levels of causation, the supernatural and the human, are co-existent and simultaneous, two ways of describing the same event." Rosenmeyer insists that ascribing portrayed characters in Aeschylus should not conclude them to be either victims or agents of theological or religious activity too quickly. As Rosenmeyer states: "[T]he text defines their being. For a critic to construct an Aeschylean theology would be as quixotic as designing a typology of Aeschylean man. The needs of the drama prevail."[32]

In a rare comparison of Prometheus in Aeschylus with Oedipus in Sophocles, Harold Bloom states that "Freud called Oedipus an 'immoral play,' since the gods ordained incest and parricide. Oedipus therefore participates in our universal unconscious sense of guilt, but on this reading so do the gods" [...] "I sometimes wish that Freud had turned to Aeschylus instead, and given us the Prometheus complex rather than the Oedipus complex."[33]

Karl-Martin Dietz states that in contrast to Hesiod's, in Aeschylus' oeuvre, Prometheus stands for the "Ascent of humanity from primitive beginnings to the present level of civilisation."[18]

Plato and philosophy

Olga Raggio, in her study "The Myth of Prometheus", attributes Plato in the Protagoras as an important contributor to the early development of the Prometheus myth.[34] Raggio indicates that many of the more challenging and dramatic assertions which Aeschylean tragedy explores are absent from Plato's writings about Prometheus.[35]

As summarised by Raggio,

After the gods have moulded men and other living creatures with a mixture of clay and fire, the two brothers Epimetheus and Prometheus are called to complete the task and distribute among the newly born creatures all sorts of natural qualities. Epimetheus sets to work but, being unwise, distributes all the gifts of nature among the animals, leaving men naked and unprotected, unable to defend themselves and to survive in a hostile world. Prometheus then steals the fire of creative power from the workshop of Athena and Hephaistos and gives it to mankind.

Raggio then goes on to point out Plato's distinction of creative power (techne), which is presented as superior to merely natural instincts (physis).

For Plato, only the virtues of "reverence and justice can provide for the maintenance of a civilised society – and these virtues are the highest gift finally bestowed on men in equal measure."[36] The ancients by way of Plato believed that the name Prometheus derived from the Greek prefix pro- (before) + manthano (intelligence) and the agent suffix -eus, thus meaning "Forethinker".

In his dialogue titled Protagoras, Plato contrasts Prometheus with his dull-witted brother Epimetheus, "Afterthinker".[37][38] In Plato's dialogue Protagoras, Protagoras asserts that the gods created humans and all the other animals, but it was left to Prometheus and his brother Epimetheus to give defining attributes to each. As no physical traits were left when the pair came to humans, Prometheus decided to give them fire and other civilising arts.[39]

Athenian religious dedication and observance

It is understandable that since Prometheus was considered a Titan and not one of the Olympian gods that there would be an absence of evidence, with the exception of Athens, for the direct religious devotion to his worship. Despite his importance to the myths and imaginative literature of ancient Greece, the religious cult of Prometheus during the Archaic and Classical periods seems to have been limited.[40] Writing in the 2nd century AD, the satirist Lucian points out that while temples to the major Olympians were everywhere, none to Prometheus is to be seen.[41]

Athens was the exception, here Prometheus was worshipped alongside Athene and Hephaistos.[42] The altar of Prometheus in the grove of the Academy was the point of origin for several significant processions and other events regularly observed on the Athenian calendar. For the Panathenaic festival, arguably the most important civic festival at Athens, a torch race began at the altar, which was located outside the sacred boundary of the city, and passed through the Kerameikos, the district inhabited by potters and other artisans who regarded Prometheus and Hephaestus as patrons.[43] The race then travelled to the heart of the city, where it kindled the sacrificial fire on the altar of Athena on the Acropolis to conclude the festival.[44] These footraces took the form of relays in which teams of runners passed off a flaming torch. According to Pausanias (2nd century AD), the torch relay, called lampadedromia or lampadephoria, was first instituted at Athens in honour of Prometheus.[45]

By the Classical period, the races were run by ephebes also in honour of Hephaestus and Athena.[46] Prometheus' association with fire is the key to his religious significance[40] and to the alignment with Athena and Hephaestus that was specific to Athens and its "unique degree of cultic emphasis" on honouring technology.[47] The festival of Prometheus was the Prometheia. The wreaths worn symbolised the chains of Prometheus.[48] There is a pattern of resemblances between Hephaistos and Prometheus. Although the classical tradition is that Hephaistos split Zeus's head to allow Athene's birth, that story has also been told of Prometheus. A variant tradition makes Prometheus the son of Hera like Hephaistos.[49] Ancient artists depict Prometheus wearing the pointed cap of an artist or artisan, like Hephaistos, and also the crafty hero Odysseus. The artisan's cap was also depicted as worn by the Cabeiri,[50] supernatural craftsmen associated with a mystery cult known in Athens in classical times, and who were associated with both Hephaistos and Prometheus. Kerényi suggests that Hephaistos may in fact be the "successor" of Prometheus, despite Hephaistos being himself of archaic origin.[51]

Pausanias recorded a few other religious sites in Greece devoted to Prometheus. Both Argos and Opous claimed to be Prometheus' final resting place, each erecting a tomb in his honour. The Greek city of Panopeus had a cult statue that was supposed to honour Prometheus for having created the human race there.[39]

Aesthetic tradition in Athenian art

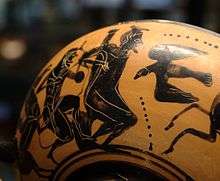

Prometheus' torment by the eagle and his rescue by Heracles were popular subjects in vase paintings of the 6th to 4th centuries BC. He also sometimes appears in depictions of Athena's birth from Zeus' forehead. There was a relief sculpture of Prometheus with Pandora on the base of Athena's cult statue in the Athenian Parthenon of the 5th century BC. A similar rendering is also found at the great altar of Zeus at Pergamon from the second century BC.

The event of the release of Prometheus from captivity was frequently revisited on Attic and Etruscan vases between the sixth and fifth centuries BC. In the depiction on display at the Museum of Karlsruhe and in Berlin, the depiction is that of Prometheus confronted by a menacing large bird (assumed to be the eagle) with Hercules approaching from behind shooting his arrows at it.[52] In the fourth century this imagery was modified to depicting Prometheus bound in a cruciform manner, possibly reflecting an Aeschylus-inspired manner of influence, again with an eagle and with Hercules approaching from the side.[53]

Other authors

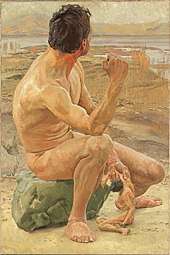

Some two dozen other Greek and Roman authors retold and further embellished the Prometheus myth from as early as the 5th century BC (Diodorus, Herodorus) into the 4th century AD. The most significant detail added to the myth found in, e.g., Sappho, Aesop and Ovid[54] was the central role of Prometheus in the creation of the human race. According to these sources, Prometheus fashioned humans out of clay.

Although perhaps made explicit in the Prometheia, later authors such as Hyginus, the Bibliotheca, and Quintus of Smyrna would confirm that Prometheus warned Zeus not to marry the sea nymph Thetis. She is consequently married off to the mortal Peleus, and bears him a son greater than the father – Achilles, Greek hero of the Trojan War. Pseudo-Apollodorus moreover clarifies a cryptic statement (1026–29) made by Hermes in Prometheus Bound, identifying the centaur Chiron as the one who would take on Prometheus' suffering and die in his place.[39] Reflecting a myth attested in Greek vase paintings from the Classical period, Pseudo-Apollodorus places the Titan (armed with an axe) at the birth of Athena, thus explaining how the goddess sprang forth from the forehead of Zeus.[39]

Other minor details attached to the myth include: the duration of Prometheus' torment;[55][56] the origin of the eagle that ate the Titan's liver (found in Pseudo-Apollodorus and Hyginus); Pandora's marriage to Epimetheus (found in Pseudo-Apollodorus); myths surrounding the life of Prometheus' son, Deucalion (found in Ovid and Apollonius of Rhodes); and Prometheus' marginal role in the myth of Jason and the Argonauts (found in Apollonius of Rhodes and Valerius Flaccus).[39]

"Variants of legends containing the Prometheus motif are widespread in the Caucasus" region, reports Hunt,[57] who gave ten stories related to Prometheus from ethno-linguistic groups in the region.

Zahhak, an evil figure in Iranian mythology, also ends up eternally chained on a mountainside – though the rest of his career is dissimilar to that of Prometheus.

Late Roman antiquity

The three most prominent aspects of the Prometheus myth have parallels within the beliefs of many cultures throughout the world (see creation of man from clay, theft of fire, and references for eternal punishment). It is the first of these three which has drawn attention to parallels with the biblical creation account related in the religious symbolism expressed in the book of Genesis.

As stated by Olga Raggio,[58] "The Prometheus myth of creation as a visual symbol of the Neoplatonic concept of human nature, illustrated in (many) sarcophagi, was evidently a contradiction of the Christian teaching of the unique and simultaneous act of creation by the Trinity." This Neoplatonism of late Roman antiquity was especially stressed by Tertullian[59] who recognised both difference and similarity of the biblical deity with the mythological figure of Prometheus.

The imagery of Prometheus and the creation of man used for the purposes of the representation of the creation of Adam in biblical symbolism is also a recurrent theme in the artistic expression of late Roman antiquity. Of the relatively rare expressions found of the creation of Adam in those centuries of late Roman antiquity, one can single out the so-called "Dogma sarcophagus" of the Lateran Museum where three figures are seen (in representation of the theological trinity) in making a benediction to the new man. Another example is found where the prototype of Prometheus is also recognisable in the early Christian era of late Roman antiquity. This can be found upon a sarcophagus of the Church at Mas d'Aire[60] as well, and in an even more direct comparison to what Raggio refers to as "a coursely carved relief from Campli (Teramo)[61] (where) the Lord sits on a throne and models the body of Adam, exactly like Prometheus." Still another such similarity is found in the example found on a Hellenistic relief presently in the Louvre in which the Lord gives life to Eve through the imposition of his two fingers on her eyes recalling the same gesture found in earlier representations of Prometheus.[58]

In Georgian mythology, Amirani is a cultural hero who challenged the chief god and, like Prometheus, was chained on the Caucasian mountains where birds would eat his organs. This aspect of the myth had a significant influence on the Greek imagination. It is recognisable from a Greek gem roughly dated to the time of the Hesiod poems, which show Prometheus with hands bound behind his body and crouching before a bird with long wings.[62] This same image would also be used later in the Rome of the Augustan age as documented by Furtwangler.[63]

In the often cited and highly publicised interview between Joseph Campbell and Bill Moyers on Public Television, the author of The Hero with a Thousand Faces presented his view on the comparison of Prometheus and Jesus.[64] Moyers asked Campbell the question in the following words, "In this sense, unlike heroes such as Prometheus or Jesus, we're not going on our journey to save the world but to save ourselves." To which Campbell's well-known response was that, "But in doing that, you save the world. The influence of a vital person vitalizes, there's no doubt about it. The world without spirit is a wasteland. People have the notion of saving the world by shifting things around, changing the rules [...] No, no! Any world is a valid world if it's alive. The thing to do is to bring life to it, and the only way to do that is to find in your own case where the life is and become alive yourself." For Campbell, Jesus mortally suffered on the Cross while Prometheus eternally suffered while chained to a rock, and each of them received punishment for the gift which they bestowed to humankind, for Jesus this was the gift of propitiation from Heaven, and, for Prometheus this was the gift of fire from Olympus.[64]

Significantly, Campbell is also clear to indicate the limits of applying the metaphors of his methodology in his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces too closely in assessing the comparison of Prometheus and Jesus. Of the four symbols of suffering associated with Jesus after his trial in Jerusalem (i) the crown of thorns, (ii) the scourge of whips, (iii) the nailing to the Cross, and (iv) the spearing of his side, it is only this last one which bears some resemblance to the eternal suffering of Prometheus' daily torment of an eagle devouring a replenishing organ, his liver, from his side.[65] For Campbell, the striking contrast between the New Testament narratives and the Greek mythological narratives remains at the limiting level of the cataclysmic eternal struggle of the eschatological New Testament narratives occurring only at the very end of the biblical narratives in the Apocalypse of John (12:7) where, "Michael and his angels fought against the dragon. The dragon and his angels fought back, but they were defeated, and there was no longer any place for them in heaven." This eschatological and apocalyptic setting of a Last Judgement is in precise contrast to the Titanomachia of Hesiod which serves its distinct service to Greek mythology as its Prolegomenon, bracketing all subsequent mythology, including the creation of humanity, as coming after the cosmological struggle between the Titans and the Olympian gods.[64]

It remains a continuing debate among scholars of comparative religion and the literary reception[66] of mythological and religious subject matter as to whether the typology of suffering and torment represented in the Prometheus myth finds its more representative comparisons with the narratives of the Hebrew scriptures or with the New Testament narratives. In the Book of Job, significant comparisons can be drawn between the sustained suffering of Job in comparison to that of eternal suffering and torment represented in the Prometheus myth. With Job, the suffering is at the acquiescence of heaven and at the will of the demonic, while in Prometheus the suffering is directly linked to Zeus as the ruler of Olympus. The comparison of the suffering of Jesus after his sentencing in Jerusalem is limited to the three days, from Thursday to Saturday, and leading to the culminating narratives corresponding to Easter Sunday. The symbolic import for comparative religion would maintain that suffering related to justified conduct is redeemed in both the Hebrew scriptures and the New Testament narratives, while in Prometheus there remains the image of a non-forgiving deity, Zeus, who nonetheless requires reverence.[64]

Writing in late antiquity of the fourth and fifth century, the Latin commentator Marcus Servius Honoratus explained that Prometheus was so named because he was a man of great foresight (vir prudentissimus), possessing the abstract quality of providentia, the Latin equivalent of Greek promētheia (ἀπὸ τής πρόμηθείας).[67] Anecdotally, the Roman fabulist Phaedrus (c.15 BC – c.50 AD) attributes to Aesop a simple etiology for homosexuality, in Prometheus' getting drunk while creating the first humans and misapplying the genitalia.[68]

Middle Ages

Perhaps the most influential book of the Middle Ages upon the reception of the Prometheus myth was the mythological handbook of Fulgentius Placiades. As stated by Raggio,[69] "The text of Fulgentius, as well as that of (Marcus) Servius [...] are the main sources of the mythological handbooks written in the ninth century by the anonymous Mythographus Primus and Mythographus Secundus. Both were used for the more lengthy and elaborate compendium by the English scholar Alexander Neckman (1157–1217), the Scintillarium Poetarum, or Poetarius."[69] The purpose of his books was to distinguish allegorical interpretation from the historical interpretation of the Prometheus myth. Continuing in this same tradition of the allegorical interpretation of the Prometheus myth, along with the historical interpretation of the Middle Ages, is the Genealogiae of Giovanni Boccaccio. Boccaccio follows these two levels of interpretation and distinguishes between two separate versions of the Prometheus myth. For Boccaccio, Prometheus is placed "In the heavens where all is clarity and truth, [Prometheus] steals, so to speak, a ray of the divine wisdom from God himself, source of all Science, supreme Light of every man."[70] With this, Boccaccio shows himself moving from the mediaeval sources with a shift of accent towards the attitude of the Renaissance humanists.

Using a similar interpretation to that of Boccaccio, Marsilio Ficino in the fifteenth century updated the philosophical and more sombre reception of the Prometheus myth not seen since the time of Plotinus. In his book written in 1476–77 titled Quaestiones Quinque de Mente, Ficino indicates his preference for reading the Prometheus myth as an image of the human soul seeking to obtain supreme truth. As Olga Raggio summarises Ficino's text, "The torture of Prometheus is the torment brought by reason itself to man, who is made by it many times more unhappy than the brutes. It is after having stolen one beam of the celestial light [...] that the soul feels as if fastened by chains and [...] only death can release her bonds and carry her to the source of all knowledge."[70] This sombreness of attitude in Ficino's text would be further developed later by Charles de Bouelles' Liber de Sapiente of 1509 which presented a mix of both scholastic and Neoplatonic ideas.

Renaissance

After the writings of both Boccaccio and Ficino in the late Middle Ages about Prometheus, interest in the Titan shifted considerably in the direction of becoming subject matter for painters and sculptors alike. Among the most famous examples is that of Piero di Cosimo from about 1510 presently on display at the museums of Munich and Strasburg (see Inset). Raggio summarises the Munich version[71] as follows; "The Munich panel represents the dispute between Epimetheus and Prometheus, the handsome triumphant statue of the new man, modelled by Prometheus, his ascension to the sky under the guidance of Minerva; the Strasburg panel shows in the distance Prometheus lighting his torch at the wheels of the Sun, and in the foreground on one side, Prometheus applying his torch to the heart of the statue and, on the other, Mercury fastening him to a tree." All the details are evidently borrowed from Boccaccio's Genealogiae.

The same reference to the Genealogiae can be cited as the source for the drawing by Parmigianino presently located in the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York City.[72] In the drawing, a very noble rendering of Prometheus is presented which evokes the memory of Michelangelo's works portraying Jehovah. This drawing is perhaps one of the most intense examples of the visualisation of the myth of Prometheus from the Renaissance period.

Writing in the late British Renaissance, William Shakespeare uses the Promethean allusion in the famous death scene of Desdemona in his tragedy of Othello. Othello in contemplating the death of Desdemona asserts plainly that he cannot restore the "Promethean heat" to her body once it has been extinguished. For Shakespeare, the allusion is clearly to the interpretation of the fire from the heat as the bestowing of life to the creation of man from clay by Prometheus after it was stolen from Olympus. The analogy bears direct resemblance to the biblical narrative of the creation of life in Adam through the bestowed breathing of the creator in Genesis. Shakespeare's symbolic reference to the "heat" associated with Prometheus' fire is to the association of the gift of fire to the mythological gift or theological gift of life to humans.

Post-Renaissance

The myth of Prometheus has been a favourite theme of Western art and literature in the post-renaissance and post-Enlightenment tradition and, occasionally, in works produced outside the West.

Post-Renaissance literary arts

For the Romantic era, Prometheus was the rebel who resisted all forms of institutional tyranny epitomised by Zeus – church, monarch, and patriarch. The Romantics drew comparisons between Prometheus and the spirit of the French Revolution, Christ, the Satan of John Milton's Paradise Lost, and the divinely inspired poet or artist. Prometheus is the lyrical "I" who speaks in Goethe's Sturm und Drang poem "Prometheus" (written c. 1772–74, published 1789), addressing God (as Zeus) in misotheist accusation and defiance. In Prometheus Unbound (1820), a four-act lyrical drama, Percy Bysshe Shelley rewrites the lost play of Aeschylus so that Prometheus does not submit to Zeus (under the Latin name Jupiter), but instead supplants him in a triumph of the human heart and intellect over tyrannical religion. Lord Byron's poem "Prometheus" also portrays the Titan as unrepentant. As documented by Olga Raggio, other leading figures among the great Romantics included Byron, Longfellow and Nietzsche as well.[34] Mary Shelley's 1818 novel Frankenstein is subtitled "The Modern Prometheus", in reference to the novel's themes of the over-reaching of modern humanity into dangerous areas of knowledge.

Goethe's poems

Prometheus is a poem by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, in which a character based on the mythic Prometheus addresses God (as Zeus) in a romantic and misotheist tone of accusation and defiance. The poem was written between 1772 and 1774. It was first published fifteen years later in 1789. It is an important work as it represents one of the first encounters of the Prometheus myth with the literary Romantic movement identified with Goethe and with the Sturm und Drang movement.

The poem has appeared in Volume 6 of Goethe's poems (in his Collected Works) in a section of Vermischte Gedichte (assorted poems), shortly following the Harzreise im Winter. It is immediately followed by "Ganymed", and the two poems are written as informing each other according to Goethe's plan in their actual writing. Prometheus (1774) was originally planned as a drama but never completed by Goethe, though the poem is inspired by it. Prometheus is the creative and rebellious spirit rejected by God and who angrily defies him and asserts himself. Ganymede, by direct contrast, is the boyish self who is both adored and seduced by God. As a high Romantic poet and a humanist poet, Goethe presents both identities as contrasting aspects of the Romantic human condition.

The poem offers direct biblical connotations for the Prometheus myth which was unseen in any of the ancient Greek poets dealing with the Prometheus myth in either drama, tragedy, or philosophy. The intentional use of the German phrase "Da ich ein Kind war..." ("When I was a child"): the use of Da is distinctive, and with it Goethe directly applies the Lutheran translation of Saint Paul's First Epistle to the Corinthians, 13:11: "Da ich ein Kind war, da redete ich wie ein Kind..." ("When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things"). Goethe's Prometheus is significant for the contrast it evokes with the biblical text of the Corinthians rather than for its similarities.

In his book titled Prometheus: Archetypal Image of Human Existence, C. Kerényi states the key contrast between Goethe's version of Prometheus with the ancient Greek version.[73] As Kerényi states, "Goethe's Prometheus had Zeus for father and a goddess for mother. With this change from the traditional lineage the poet distinguished his hero from the race of the Titans." For Goethe, the metaphorical comparison of Prometheus to the image of the Son from the New Testament narratives was of central importance, with the figure of Zeus in Goethe's reading being metaphorically matched directly to the image of the Father from the New Testament narratives.

Percy Bysshe Shelley

Percy Shelley published his four-act lyrical drama titled Prometheus Unbound in 1820. His version was written in response to the version of myth as presented by Aeschylus and is orientated to the high British Idealism and high British Romanticism prevailing in Shelley's own time. Shelley, as the author himself discusses, admits the debt of his version of the myth to Aeschylus and the Greek poetic tradition which he assumes is familiar to readers of his own lyrical drama. For example, it is necessary to understand and have knowledge of the reason for Prometheus' punishment if the reader is to form an understanding of whether the exoneration portrayed by Shelley in his version of the Prometheus myth is justified or unjustified. The quote of Shelley's own words describing the extent of his indebtedness to Aeschylus has been published in numerous sources publicly available.

The literary critic Harold Bloom in his book Shelley's Mythmaking expresses his high expectation of Shelley in the tradition of mythopoeic poetry. For Bloom, Percy Shelley's relationship to the tradition of mythology in poetry "culminates in 'Prometheus'. The poem provides a complete statement of Shelley's vision."[74] Bloom devotes two full chapters in this book to Shelley's lyrical drama Prometheus Unbound which was among the first books Bloom had ever written, originally published in 1959.[75] Following his 1959 book, Bloom edited an anthology of critical opinions on Shelley for Chelsea House Publishers where he concisely stated his opinion as, "Shelley is the unacknowledged ancestor of Wallace Stevens' conception of poetry as the Supreme Fiction, and Prometheus Unbound is the most capable imagining, outside of Blake and Wordsworth, that the Romantic quest for a Supreme Fiction has achieved."[76]

Within the pages of his Introduction to the Chelsea House edition on Percy Shelley, Harold Bloom also identifies the six major schools of criticism opposing Shelley's idealised mythologising version of the Prometheus myth. In sequence, the opposing schools to Shelley are given as: (i) The school of "common sense", (ii) The Christian orthodox, (iii) The school of "wit", (iv) Moralists, of most varieties, (v) The school of "classic" form, and (vi) The Precisionists, or concretists.[77] Although Bloom is least interested in the first two schools, the second one on the Christian orthodox has special bearing on the reception of the Prometheus myth during late Roman antiquity and the synthesis of the New Testament canon. The Greek origins of the Prometheus myth have already discussed the Titanomachia as placing the cosmic struggle of Olympus at some point in time preceding the creation of humanity, while in the New Testament synthesis there was a strong assimilation of the prophetic tradition of the Hebrew prophets and their strongly eschatological orientation. This contrast placed a strong emphasis within the ancient Greek consciousness as to the moral and ontological acceptance of the mythology of the Titanomachia as an accomplished mythological history, whereas for the synthesis of the New Testament narratives this placed religious consciousness within the community at the level of an anticipated eschaton not yet accomplished. Neither of these would guide Percy Shelley in his poetic retelling and re-integration of the Prometheus myth.[78]

To the Socratic Greeks, one important aspect of the discussion of religion would correspond to the philosophical discussion of 'becoming' with respect to the New Testament syncretism rather than the ontological discussion of 'being' which was more prominent in the ancient Greek experience of mythologically oriented cult and religion.[79] For Percy Shelley, both of these reading were to be substantially discounted in preference to his own concerns for promoting his own version of an idealised consciousness of a society guided by the precepts of High British Romanticism and High British Idealism.[80]

Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus

Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus, written by Mary Shelley when she was 18, was published in 1818, two years before Percy Shelley's above-mentioned play. It has endured as one of the most frequently revisited literary themes in twentieth century film and popular reception with few rivals for its sheer popularity among even established literary works of art. The primary theme is a parallel to the aspect of the Prometheus myth which concentrates on the creation of man by the Titans, transferred and made contemporary by Shelley for British audiences of her time. The subject is that of the creation of life by a scientist, thus bestowing life through the application and technology of medical science rather than by the natural acts of reproduction. The short novel has been adapted into many films and productions ranging from the early versions with Boris Karloff to later versions including Kenneth Branagh's 1994 film adaptation.

Twentieth century

Franz Kafka wrote a short piece titled "Prometheus," outlining what he saw as his perspective on four aspects of his myth:

According to the first, he was clamped to a rock in the Caucasus for betraying the secrets of the gods to men, and the gods sent eagles to feed on his liver, which was perpetually renewed.

According to the second, Prometheus, goaded by the pain of the tearing beaks, pressed himself deeper and deeper into the rock until he became one with it.

According to the third, his treachery was forgotten in the course of thousands of years, forgotten by the gods, the eagles, forgotten by himself.

According to the fourth, everyone grew weary of the meaningless affair. The gods grew weary, the eagles grew weary, the wound closed wearily.

There remains the inexplicable mass of rock. The legend tried to explain the inexplicable. As it came out of a substratum of truth it had in turn to end in the inexplicable.[81]

This short piece by Kafka concerning his interest in Prometheus was supplemented by two other mythological pieces written by him. As stated by Reiner Stach, "Kafka's world was mythical in nature, with Old Testament and Jewish legends providing the templates. It was only logical (even if Kafka did not state it openly) that he would try his hand at the canon of antiquity, re-interpreting it and incorporating it into his own imagination in the form of allusions, as in 'The Silence of the Sirens,' 'Prometheus,' and 'Poseidon.'"[82] Among contemporary poets, the British poet Ted Hughes wrote a 1973 collection of poems titled Prometheus on His Crag. The Nepali poet Laxmi Prasad Devkota (d. 1949) also wrote an epic titled Prometheus (प्रमीथस).

In his 1952 book, Lucifer and Prometheus, Zvi Werblowsky presented the speculatively derived Jungian construction of the character of Satan in Milton's celebrated poem Paradise Lost. Werblowsky applied his own Jungian style of interpretation to appropriate parts of the Prometheus myth for the purpose of interpreting Milton. A reprint of his book in the 1990s by Routledge Press included an introduction to the book by Carl Jung. Some Gnostics have been associated with identifying the theft of fire from heaven as embodied by the fall of Lucifer "the Light Bearer".[83]

Ayn Rand cited the Prometheus myth in Anthem, The Fountainhead, and Atlas Shrugged, using the mythological character as a metaphor for creative people rebelling against the confines of modern society.

The Eulenspiegel Society began the magazine Prometheus in the early 1970s;[84] it is a decades-long-running magazine exploring issues important to kinksters, ranging from art and erotica, to advice columns and personal ads, to conversation about the philosophy of consensual kink. The magazine now exists online.[85]

The artificial chemical element promethium is named after Prometheus.

Post-Renaissance aesthetic tradition

Visual arts

_de_Jos%C3%A9_Clemente_Orozco_en_Pomona_College.jpg)

Prometheus has been depicted in a number of well-known artworks, including Mexican muralist José Clemente Orozco's Prometheus fresco at Pomona College[86][87] and Paul Manship's bronze sculpture Prometheus at Rockefeller Center in Manhattan.

Classical music, opera, and ballet

Works of classical music, opera, and ballet directly or indirectly inspired by the myth of Prometheus have included renderings by some of the major composers of both the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In this tradition, the orchestral representation of the myth has received the most sustained attention of composers. These have included the symphonic poem by Franz Liszt titled Prometheus from 1850, among his other Symphonic Poems (No. 5, S.99).[88] Alexander Scriabin composed Prometheus: Poem of Fire, Opus 60 (1910),[89] also for orchestra.[90] In the same year Gabriel Fauré composed his three-act opera Prométhée (1910).[91] Charles-Valentin Alkan composed his Grande sonate 'Les quatre âges' (1847), with the 4th movement entitled "Prométhée enchaîné" (Prometheus Bound).[92] Beethoven composed the score to a ballet version of the myth titled The Creatures of Prometheus (1801).[93]

An adaptation of Goethe's poetic version of the myth was composed by Hugo Wolf, Prometheus (Bedecke deinen Himmel, Zeus, 1889), as part of his Goethe-lieder for voice and piano,[94] later transcribed for orchestra and voice.[95] An opera of the myth was composed by Carl Orff titled Prometheus (1968),[96][97] using Aeschylus' Greek language Prometheia.[98] Another work inspired by the myth, Prometeo (Prometheus), was composed by Luigi Nono between 1981 and 1984 and can be considered a sequence of nine cantatas. The libretto in Italian was written by Massimo Cacciari, and selects from texts by such varied authors as Aeschylus, Walter Benjamin and Rainer Maria Rilke and presents the different versions of the myth of Prometheus without telling any version literally.

See also

- Prometheism

- Tityos, a Giant chained in Tartarus punished by two vultures who eat his regenerating liver.

Notes

- Smith, "Prometheus".

- William Hansen, Classical Mythology: A Guide to the Mythical World of the Greeks and Romans (Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 32, 48–50, 69–73, 93, 96, 102–104, 140; as trickster figure, p. 310.

- Krishna, Gopi; Hillman, James (commentary) (1970). Kundalini – the evolutionary energy in man. London: Stuart & Watkins. p. 77. SBN 7224 0115 9. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05.

- This is comparable to the punishment of Tityos, a giant who is chained by Zeus in Tartarus and tortured by two vultures who eat his regenerating liver each day.

- Lewis Richard Farnell, The Cults of the Greek States (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1896), vol. 1, pp. 36, 49, 75, 277, 285, 314, 346; Carol Dougherty, Prometheus (Routledge, 2006), p. 42ff..

- Smith, "Prometheus".

- Quoted in Kerényi (1997), p. 50.

- Kerényi (1997), pp. 50, 63.

- Fortson, Benjamin W. (2004). Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction. Blackwell Publishing, p. 27; Williamson 2004, 214–15; Dougherty, Carol (2006). Prometheus. p. 4.

- Cook, Arthur Bernard (1914). Zeus: A Study in Ancient Religion, Volume 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 329. Retrieved 5 February 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Diodurus quoted in Cook (1914), p. 325.

- Stephanie West. "Prometheus Orientalized" page 147 Museum Helveticum Vol. 51, No. 3 (1994), pp. 129–149 (21 pages)

- Chapter 3 (with notes) in "Gifts of Fire– An Historical Analysis of the Promethean Myth for the Light it Casts on the Philosophical Philanthropy of Protagoras, Socrates and Plato; and Prolegomena to Consideration of the Same in Bacon and Nietzsche" Marty James John Šulek Submitted to and accepted byAdditi the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Philanthropic Studies Indiana University December 2011 Accessed online at https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/46957093.pdf on 16/02/2019 NB. This source is used for its review of the literature on the Indo-European and Vedic origin of Prometheus rather than for conclusions reached in it.

- M. L. West commentaries on Hesiod, W.J. Verdenius commentaries on Hesiod, and R. Lamberton's Hesiod, pp.95–100.

- Casanova, La famiglia di Pandora: analisi filologica dei miti di Pandora e Prometeo nella tradizione esiodea (Florence) 1979.

- Hesiod, Theogony, 526–33.

- In this Casanova is joined by some editors of Theogony.

- Karl-Martin Dietz: Metamorphosen des Geistes. Band 1. Prometheus – vom Göttlichen zum menschlichen Wissen. Stuttgart 1989, p. 66.

- Reinhardt, Karl. Aischylos als Regisseur und Theologe, p. 30.

- West, M. L. (2002). "'Eumelos': A Corinthian Epic Cycle?". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 122: 109–133. doi:10.2307/3246207. JSTOR 3246207CS1 maint: ref=harv (link), pp. 110–111.

- Philippson, Paula (1944). Untersuchungen uber griechischen Mythos: Genealogie als mythische Form. Zürich, Switzerland: Rhein-Verlag.

- Stephanie West. "Prometheus Orientalized" page 147 Museum Helveticum Vol. 51, No. 3 (1994), pp. 129–149 (21 pages)

- West (2002), pp. 114, and 110–118 for general discussion of Titanomachy.

- Aeschylus. "Prometheus Bound". Theoi.com. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- Some of these changes are rather minor. For instance, rather than being the son of Iapetus and Clymene Prometheus becomes the son of Themis who is identified with Gaia. In addition, the chorus makes a passing reference (561) to Prometheus' wife Hesione, whereas a fragment from Hesiod's Catalogue of Women fr. 4 calls her "Pryneie", a possible corruption for Pronoia.

- West (2002), pp. 114, and 110–118 for general discussion of Titanomachy.

- William Lynch, S.J. Christ and Prometheus. University of Notre Dame Press.

- Lynch, pp. 4–5.

- Bloom, Harold (2002). Bloom's Major Dramatists: Aeschylus. Chelsea House Publishers.

- de Romilly, Jacqueline (1968). Time in Greek Tragedy. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1968), pp. 72–73, 77–81.

- "Bloom's Major Dramatists," pp. 14–15.

- Rosenmeyer, Thomas (1982). The Art of Aeschylus. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982, pp. 270–71, 281–83.

- Harold Bloom. Bloom's Guides: Oedipus Rex, Chelsea Press, New York, 2007, p. 8.

- Raggio, Olga (1958). "The Myth of Prometheus: Its Survival and Metamorphoses up to the Eighteenth Century". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 21 (1/2): 44–62. doi:10.2307/750486. JSTOR 750486.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Plato (1958). Protagoras, p. 320 ff.

- Raggio (1958), p. 45.

- Plato, Protagoras

- Hansen, Classical Mythology, p. 159.

- "Theoi Project: Prometheus". Theoi.com. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- Dougherty, Prometheus, p. 46.

- Lucian, Prometheus 14.

- Kerényi (1997), p. 58.

- On the association of the cults of Prometheus and Hephaestus, see also Scholiast to Sophocles, Oedipus at Colonus 56, as cited by Robert Parker, Polytheism and Society at Athens (Oxford University Press, 2007), p. 472.

- Pausanias 1.30.2; Scholiast to Plato, Phaedrus 231e; Dougherty, Prometheus, p. 46; Peter Wilson, The Athenian Institution of the Khoregia: The Chorus, the City and the Stage (Cambridge University Press, 2000), p. 35.

- Pausanias 1.30.2.

- Possibly also Pan; Wilson, The Athenian Institution of the Khoregia, p. 35.

- Farnell, The Cults of the Greek States, vol. 1, p. 277; Parker, Polytheism and Society at Athens, p. 409.

- Aeschylus, Suppliants frg. 202, as cited by Parker, Polytheism and Society at Athens, p. 142.

- Kerényi (1997), p. 59.

- Kerényi (1997), pp. 50–51.

- Kerényi (1997), pp. 57–59.

- O. Jahn, Archeologische Beitrage, Berlin, 1847, pl. VIII (Amphora from Chiusi).

- Milchhofer, Die Befreiung des Prometheus in Berliner Winckelmanns-Programme, 1882, p. 1ff.

- Cf. Ovid, Metamorphoses, I, 78ff.

- "30 Years". Mlahanas.de. 1997-11-10. Archived from the original on 2012-05-30. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- "30,000 Years". Theoi.com. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- p. 14. Hunt, David. 2012. Legends of the Caucasus. London: Saqi Books.

- Raggio (1958), p. 48.

- Tertullian. Apologeticum XVIII,3.

- Wilpert, J. (1932), I Sarcofagi Christiani, II, p. 226.

- Wilpert, I, pl CVI, 2.

- Furtwangler, Die Antiken Gemmen, 1910, I, pl. V, no. 37.

- Furtwangler, op. cit., pl. XXXVII, nos. 40, 41, 45, 46.

- Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

- Lynch, William. Christ and Prometheus.

- Dostoevski, Fyodor. The Brothers Karamazov, chapter on "The Grand Inquisitor".

- Servius, note to Vergil's Eclogue 6.42: Prometheus vir prudentissimus fuit, unde etiam Prometheus dictus est ἀπὸ τής πρόμηθείας, id est a providentia.

- "Dionysos". Theoi.com. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- Raggio (1958), p. 53.

- Raggio (1958), p. 54.

- Munich, Alte Pinakothek, Katalog, 1930, no. 8973. Strasburg, Musee des Beaux Arts, Catalog, 1932, no. 225.

- Parmigianino: The Drawings, Sylvie Beguin et al. ISBN 88-422-1020-X.

- Kerényi (1997), p. 11.

- Bloom, Harold (1959). Shelley's Mythmaking, Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut, p. 9.

- Bloom (1959), Chapter 3.

- Bloom, Harold (1985). Percy Bysshe Shelley. Modern Critical Editions, p.8. Chelsea House Publishers, New York.

- Bloom, Harold (1985). Percy Bysshe Shelley. Modern Critical Editions, p. 27. Chelsea House Publishers, New York.

- Bloom, Harold (1959). Shelley's Mythmaking, Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut, p. 29.

- Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time.

- Bloom, Harold (1985). Percy Bysshe Shelley. Modern Critical Editions, p. 28. Chelsea House Publishers, New York.

- Translated by Willa and Edwin Muir. See Glatzer, Nahum N., ed. "Franz Kafka: The Complete Stories" Schocken Book, Inc.: New York, 1971.

- Stach, Reiner (3013). Kafka: The years of Insight, Princeton University Press, English translation.

- R.J. Zwi Werblowsky, Lucifer and Prometheus, as summarized by Gedaliahu G. Stroumsa, "Myth into Metaphor: The Case of Prometheus", in Gilgul: Essays on Transformation, Revolution and Permanence in the History of Religions, Dedicated to R.J. Zwi Werblowsky (Brill, 1987), p. 311; Steven M. Wasserstrom, Religion after Religion: Gershom Scholem, Mircea Eliade, and Henry Corbin at Eranos (Princeton University Press, 1999), p. 210

- "Welcome Back, 'Prometheus' | The Eulenspiegel Society". www.tes.org. Retrieved 2017-07-07.

- "Welcome Back, 'Prometheus' | The Eulenspiegel Society". www.tes.org. Retrieved 2017-07-07.

- "José Clemente Orozco's Prometheus". Pomona College. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- Sutton, Frances (28 February 2020). "Framed: 'Prometheus' — the hunk without the junk at Frary". The Student Life. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- Liszt: Les Preludes / Tasso / Prometheus / Mephisto Waltz No. 1 by Franz Liszt, Georg Solti, London Philharmonic Orchestra and Orchestre de Paris (1990).

- Scriabin: Symphony No. 3 The Divine Poem, Prometheus Op. 60 The Poem of Fire by Scriabin, Richter and Svetlanov (1995).

- Scriabin: Complete Symphonies/Piano Concerto/Prometheus/Le Poeme de l'extase by A. Scriabin (2003), Box Set.

- Prométhée; Tragédie Lyrique En 3 Actes De Jean Lorrain & F.a. Hérold (French Edition) by Fauré, Gabriel, 1845–1924, Paul Alexandre Martin, 1856–1906. Prométhée, . Duval and A.-Ferdinand (André-Ferdinand), b. 1865. Prométhée, Herold (Sep 24, 2012).

- Grand Sonata, Op. 33, "Les quatre ages" (The four ages): IV. 50 ans Promethee enchaine (Prometheus enchained): Extrement lent, Stefan Lindgren.

- Beethoven: Creatures of Prometheus by L. von Beethoven, Sir Charles Mackerras and Scottish Chamber Orchestra (2005).

- Goethe lieder. Stanislaw Richter. Audio CD (July 25, 2000), Orfeo, ASIN: B00004W1H1.

- Orff, Carl. Prometheus. Voice and Orchestra. Audio CD (February 14, 2006), Harmonia Mundi Fr., ASIN: B000BTE4LQ.

- Orff, Carl (2005). Prometheus, Audio CD (May 31, 2005), Arts Music, ASIN: B0007WQB6I.

- Orff, Carl (1999). Prometheus, Audio CD (November 29, 1999), Orfeo, ASIN: B00003CX0N.

- Prometheus libretto in modern Greek and German translation, 172 pages, Schott; Bilingual edition (June 1, 1976), ISBN 3795736412.

References

| Library resources about Prometheus |

- Alexander, Hartley Burr. The Mythology of All Races. Vol 10: North American. Boston, 1916.

- Beall, E.F., "Hesiod's Prometheus and Development in Myth", Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 52, No. 3 (Jul. – Sep., 1991), pp. 355–371. doi:10.2307/2710042. JSTOR 2710042.

- Bertagnolli, Paul A. 2007. Prometheus in Music: Representations of the Myth in the Romantic Era. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

- Dougherty, Carol. Prometheus. Taylor & Francis, 2006. ISBN 0-415-32406-8, ISBN 978-0-415-32406-9

- Gisler, Jean-Robert. 1994. "Prometheus." In Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae. Zurich and Munich: Artemis.

- Griffith, Mark. 1977. The Authenticity of Prometheus Bound. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Hynes, William J., and William G. Doty, eds. 1993. Mythical Trickster Figures: Contours, Contexts, and Criticisms. Tuscaloosa and London: Univ. of Alabama Press.

- Kerényi, C. (1997). Prometheus: Archetypal Image of Human Existence. Translated by Mannheim, Ralph. Princeton University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kraus, Walther, and Lothar Eckhardt. 1957. "Prometheus." Paulys Real-Encylopādie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft 23:653–702.

- Kreitzer, L. Joseph. 1993. Prometheus and Adam: Enduring Symbols of the Human Situation. Lanham, MD: Univ. Press of America.

- Lamberton, Robert. Hesiod, Yale University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-300-04068-7

- Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London (1873).

- Loney, Alexander C. 2014. "Hesiod's Incorporative Poetics in the Theogony and the Contradictions of Prometheus." American Journal of Philology 135.4: 503–531.

- Michelakis, Pantelis. 2013. Greek Tragedy on Screen. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Miller, Clyde L. 1978. "The Prometheus Story in Plato’s Protagoras." Interpretations: A Journal of Political Philosophy 7.2: 22–32.

- Raggio, Olga. 1958. "The Myth of Prometheus: Its Survival and Metamorphoses up to the XVIIIth Century." Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 21:44–62. doi:10.2307/750486. JSTOR 750486.

- Verdenius, Willem Jacob, A Commentary on Hesiod: Works and Days, vv. 1–382, Brill, 1985, ISBN 90-04-07465-1

- Vernant, Jean-Pierre. 1990. The Myth of Prometheus. In Myth and Society in Ancient Greece, 183–201. New York: Zone.

- West, Martin L., ed. 1966. Hesiod: Theogony. Oxford: Clarendon.

- West, Martin L., ed. 1978. Hesiod: Works and Days. Oxford: Clarendon.

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Prometheus |