Paris, Texas

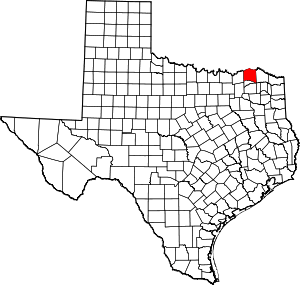

Paris is a city and county seat of Lamar County, Texas, United States. As of the 2010 census, the population of the city was 25,171. It is situated in Northeast Texas at the western edge of the Piney Woods, and 98 miles (158 km) northeast of the Dallas–Fort Worth Metroplex. Physiographically, these regions are part of the West Gulf Coastal Plain.[4]

Paris, Texas | |

|---|---|

City | |

Historic downtown Paris | |

Location of Lamar County | |

| |

| Coordinates: 33°39′45″N 95°32′52″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| County | Lamar |

| Government | |

| • City Council | Dr Steve Clifford Derrick Hughes Renae Stone Bill Trenado Linda Knox Clayton Pilgrim Paula Portugal |

| • City Manager | John Godwin |

| Area | |

| • Total | 37.07 sq mi (96.00 km2) |

| • Land | 35.19 sq mi (91.14 km2) |

| • Water | 1.88 sq mi (4.86 km2) |

| Elevation | 600 ft (183 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 25,171 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 24,847 |

| • Density | 706.08/sq mi (272.62/km2) |

| • Demonym | Parisite |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 75460-75462 |

| Area code(s) | 903/430 |

| FIPS code | 48-55080 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1364810[3] |

| Website | paristexas.gov |

Following a tradition of American cities named "Paris" (named after France's capital), the city commissioned a 65-foot (20 m) replica of the Eiffel Tower in 1993 and installed it on site of the Love Civic Center, southeast of the town square. In 1998, presumably as a response to the 1993 construction of a 60-foot (18 m) tower in Paris, Tennessee, the city placed a giant red cowboy hat atop its tower. The current Eiffel Tower replica is at least the second one; an earlier replica constructed of wood was destroyed by a tornado.

History

Present-day Lamar County was part of Red River County during the Republic of Texas. By 1840, population growth necessitated the organization of a new county. George Washington Wright, who had served in the Third Congress of the Republic of Texas as a representative from Red River County, was a major proponent of the new county. The Fifth Congress established the new county on December 17, 1840, and named it after Mirabeau B. Lamar,[5] who was the first Vice President and the second President of the Republic of Texas.

Lamar County was one of the 18 Texas counties that voted against secession on February 23, 1861.[6]

In 1877, 1896, and 1916, major fires in the city forced considerable rebuilding. The 1916 fire destroyed almost half the town and caused an estimated $11 million in property damage. The fire ruined most of the central business district and swept through a residential area. The burned structures included the Federal Building and Post Office, the Lamar County Courthouse and Jail, City Hall, most commercial buildings, and several churches.[7]

In 1893, black teenager Henry Smith was accused of murder, tortured, and then burned to death on a scaffold in front of thousands of spectators in Paris.[8] In 1920, two black brothers from the Arthur family were tied to a flagpole and burned to death at the Paris fairgrounds. The city has prominent memorials to the Confederacy, but has no acknowledgement of these killings.[8]

In 1943, the U.S. Supreme Court in Largent v. Texas struck down a Paris ordinance that prohibited a person from selling or distributing religious publications without first obtaining a city-issued permit. The Court ruled that the ordinance abridged freedom of religion, freedom of speech, and freedom of the press in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.[9]

Transportation

.png)

Paris has long been a railroad center. The Texas and Pacific reached town in 1876; the Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe Railway (later merged into the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway) and the Frisco in 1887; the Texas Midland Railroad (later Southern Pacific) in 1894; and the Paris and Mount Pleasant (Pa-Ma Line) in 1910. Paris Union Station, built 1912, served Frisco], Santa Fe, and Texas Midland passenger trains until 1956. Today, the station is used by the Lamar County Chamber of Commerce and serves as the research library for the Lamar County Genealogical Society.[10]

Historical residences

.jpg)

The city is home to several late-19th to mid-20th century stately homes. Among these is the Rufus Fenner Scott Mansion, designed by German architect J.L. Wees and constructed in 1910. The structure is solid concrete and steel with four floors. Rufus Scott was a prominent businessman known for shipping, imports, and banking. He was well known by local farmers, who bought aging transport mules from him. The Scott Mansion narrowly survived the fire of 1916. After the fire, Scott brought the architect Wees back to Paris to redesign the historic downtown area.[11]

Camp Maxey

Camp Maxey is maintained by a Texas Army National Guard unit.[12]

City rating

Paris was named the "Best Small Town in Texas" by Kevin Heubusch in his book The New Rating Guide to Life in America's Small Cities (1997).[13]

Media

Newspaper

Since 1869, The Paris News has served as the newspaper in the city of Paris. It circulates daily in the city and throughout Lamar County, as well as in neighboring Delta, Fannin, and Red River Counties in Texas and Choctaw County, Oklahoma.

Radio stations

Six radio stations are licensed in the city of Paris: KFYN, KZHN, KPLT (AM), KOYN, KBUS, KITX, and KPLT-FM.

Television

Paris is served by KXII; the low-power translator station KXIP-LD (channel 12) is in Paris.

Race relations

Race relations in Paris have a bloody history and have been deeply polarized, turbulent, and sometimes explosive.[14][15]

In the late-19th and early-20th centuries, several lynchings were staged at the Paris Fairgrounds as public spectacles, with thousands of white spectators cheering as the victims were tortured and then immolated, dismembered, or otherwise murdered.[16][14] Among the victims was Henry Smith, a teenager lynched in 1893 after the alleged rape and the murder of a 3 years old White girl. On July 7, 1920 there was the Lynching of Irving and Herman Arthur.

115 years later, in 2008, an African-American man, Brandon McClelland, was run over and dragged to death under a vehicle. Two white men were arrested, but the prosecutor cited lack of evidence and declined to press charges, and no serious subsequent attempt to find other perpetrators was made. This caused unrest in the Paris African-American community. Following this incident, an attempt by the United States Department of Justice Justice Community Relations Service to initiate a dialog between the races in the town[17] ended in failure when African-American complaints were mostly met by silent glares.[14]

A 2009 protest rally over the case let to Texas State Police intervention to prevent groups shouting "white power!" and "black power!" from coming to blows.[18] In response to the incident, civil rights activist Brenda Cherry said "I think we are probably stuck in 1930 right about now".[19] In 2007, a 14-year-old African-American girl was sentenced by a local judge to up to 7 years in a youth prison for shoving a hall monitor at Paris High School. Three months earlier, the same judge had sentenced a 14-year-old white girl to probation for arson. This sentencing disparity occasioned nationwide controversy[20] and the African-American girl was released after serving one year on orders of a special conservator appointed by the State of Texas to investigate problems with the state's juvenile-justice practices.[20]

In 2009, some African-American workers at the Turner Industries plant in the city claimed that hangman's nooses, Confederate flags, and racist graffiti were regular features of plant culture.[21] At the same time, the United States Department of Education was conducting an investigation into allegations that African-American students in Paris's schools are disciplined more harshly than white students for similar offenses.[20]

In 2015, the United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission ruled after an investigation that African-American workers at the Sara Lee Corporation plant in Paris (closed in 2011)[22] were deliberately exposed disproportionately to asbestos, black mold, and other toxins, and also were targets of racial slurs and racist graffiti.[23]

Some Paris residents deny that the town has a race-relations problem.[16][18] Judge M. C. Superville commented "I do not believe there is systematic racial discrimination in Lamar County. I do believe there is a misperception that that is going on".[19]

Geography

Paris is located at 33°39′45″N 95°32′52″W (33.662508, −95.547692).[24] According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 44.4 square miles (115 km2), of which 42.8 square miles (111 km2) are land and 1.7 square miles (4.4 km2) (3.74%) are covered by water.

Climate

Paris has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa in the Köppen climate classification). It is located in "Tornado Alley", an area largely centered in the middle of the United States in which tornadoes occur frequently because of weather patterns and geography. Paris is in USDA plant hardiness zone 8a for winter temperatures. This is cooler than its southern neighbor Dallas, and while similar to Atlanta, Georgia, it has warmer summertime temperatures. Summertime average highs reach 94 °F (34 °C) and 95 °F (35 °C) in July and August, with associated lows of 72 °F (22 °C) and 71 °F (22 °C). Winter temperatures drop to an average high of 51 °F (11 °C) and low of 30 °F (−1 °C) in January. The highest temperature on record was 115 °F (46 °C), set in August 1936, and the record low was −5 °F (−21 °C), set in 1930. Average precipitation is 47.82 in (1,215 mm). Snow is not unusual, but is by no means predictable, and years can pass with no snowfall at all.

On April 2, 1982, Paris was hit by an F4 tornado that destroyed more than 1,500 homes, and left 10 people dead, 170 injured, and 3,000 homeless. The damage toll from this tornado was estimated at US$50 million in 1982.[25]

| Climate data for Paris, Texas | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 90 (32) |

90 (32) |

94 (34) |

96 (36) |

100 (38) |

108 (42) |

111 (44) |

115 (46) |

112 (44) |

99 (37) |

94 (34) |

87 (31) |

115 (46) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 53.2 (11.8) |

57.4 (14.1) |

66 (19) |

74.7 (23.7) |

81.8 (27.7) |

90.2 (32.3) |

94.7 (34.8) |

95.2 (35.1) |

88.4 (31.3) |

78.1 (25.6) |

65.1 (18.4) |

55.4 (13.0) |

75 (24) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 42.5 (5.8) |

46.2 (7.9) |

54.5 (12.5) |

63.3 (17.4) |

71.3 (21.8) |

79.5 (26.4) |

83.6 (28.7) |

83.5 (28.6) |

76.6 (24.8) |

65.8 (18.8) |

53.7 (12.1) |

44.8 (7.1) |

63.8 (17.7) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 31.7 (−0.2) |

35 (2) |

43 (6) |

52 (11) |

60.7 (15.9) |

68.9 (20.5) |

72.5 (22.5) |

71.8 (22.1) |

64.8 (18.2) |

53.5 (11.9) |

42.4 (5.8) |

34.2 (1.2) |

52.5 (11.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −5 (−21) |

−2 (−19) |

7 (−14) |

25 (−4) |

30 (−1) |

46 (8) |

57 (14) |

43 (6) |

34 (1) |

19 (−7) |

15 (−9) |

0 (−18) |

−5 (−21) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.8 (71) |

3.1 (79) |

3.8 (97) |

4.6 (120) |

5.3 (130) |

3.9 (99) |

3.4 (86) |

2.6 (66) |

3.7 (94) |

3.8 (97) |

3.7 (94) |

3.4 (86) |

44.1 (1,120) |

| Source: [26] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 3,980 | — | |

| 1890 | 8,254 | 107.4% | |

| 1900 | 9,358 | 13.4% | |

| 1910 | 11,269 | 20.4% | |

| 1920 | 15,040 | 33.5% | |

| 1930 | 15,649 | 4.0% | |

| 1940 | 18,678 | 19.4% | |

| 1950 | 21,643 | 15.9% | |

| 1960 | 20,977 | −3.1% | |

| 1970 | 23,441 | 11.7% | |

| 1980 | 25,498 | 8.8% | |

| 1990 | 24,799 | −2.7% | |

| 2000 | 25,898 | 4.4% | |

| 2010 | 25,171 | −2.8% | |

| Est. 2019 | 24,847 | [2] | −1.3% |

| Texas Almanac[27] | |||

As of the census[28] of 2010, 25,171 people, 10,306 households, and 6,426 families resided in the city. The population density was 588.1 people per square mile (227.4/km2). The 11,883 housing units averaged 277.6 per square mile (107.3/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 70.3% White, 24.8% African American, 3.1% Native American, 1.1% Asian, and 4.1% from other races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 8.2% of the population.

Of the 10,306 households, 27.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 37.8% were married couples living together, 19.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 37.6% were not families. About 32.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 15.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.38 and the average family size was 3.01.

In the city, the population was distributed as 25.0% under the age of 18, 10.6% from 18 to 24, 24.1% from 25 to 44, 23.8% from 45 to 64, and 16.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37.1 years. For every 100 females, there were 87.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 82.9 males.

2000 census data

In 2000, the median income for a household in the city was $27,438, and for a family was $34,916. Males had a median income of $29,378 versus $20,080 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,137. About 16.5% of families and 20.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 29.0% of those under age 18 and 15.9% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

In the past, Paris was a major cotton exchange, and the county was developed as cotton plantations. While cotton is still farmed on the lands around Paris, it is no longer a major part of the economy.

Paris' one major hospital has two campuses: Paris Regional Medical Center South (formerly St. Joseph's Hospital) and Paris Regional Medical Center North (formerly McCuistion Regional Medical Center). It serves as the center of healthcare for much of Northeast Texas and Southeast Oklahoma. Both campuses are now operated jointly under the name of the Paris Regional Medical Center, a division of Essent Healthcare. Paris Regional Medical Center South Campus has recently closed and only the North Campus remains open. The health network is one of the largest employers in the Paris area.[29]

Outside of healthcare, the largest employers are Kimberly-Clark and Campbell's Soup.

| # | Employer | # of employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Essent-PRMC | 1000 |

| 2 | Campbell Soup | 900 |

| 3 | Kimberly-Clark | 800 |

| 4 | Turner Industries | 700 |

| 5 | Paris ISD | 640 |

| T-6 | North Lamar ISD | 500 |

| T-6 | Walmart | 500 |

| 8 | TCIM | 480 |

| 9 | City of Paris | 320 |

| 10 | We-Pack Logistics | 300 |

Note: PRMC is Paris Regional Medical Center.

Education

.jpg)

Elementary and secondary education is split among three main school districts:

- Paris Independent School District

- North Lamar Independent School District

- Chisum Independent School District

Prairiland ISD also serves a small portion of the town, along with Blossom ISD.

In addition, Paris Junior College provides postsecondary education. It hosts the Texas Institute of Jewelry Technology, a well-respected school of gemology, horology, and jewelry. The Industrial Technology Division offers programs in air conditioning technology, refrigeration technology, agricultural technology, drafting and computer-aided design, electronics, electromechanical technology, and welding technology.

Texas A&M University-Commerce, a major university of over 12,000 students, is located in the neighboring city of Commerce, 40 minutes southwest of Paris.

The Paris Public Library serves Paris, as does the Lamar County Genealogical Society Library.[31]

Government

.jpg)

It is governed by a city council as specified in the city's charter adopted in 1948.

State government

Paris is represented in the Texas Senate by Republican Kevin Eltife, District 1, and in the Texas House of Representatives by Republican Erwin Cain, District 3.

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice operates the Paris District Parole Office in Paris.[32]

Federal government

At the federal level, the two U.S. Senators from Texas are Republicans John Cornyn and Ted Cruz. Paris is part of Texas's 4th congressional district, represented by Republican John Ratcliffe.

The United States Postal Service operates the Paris Post Office.[33]

Transportation

Major highways

According to the Texas Transportation Commission, Paris is the second-largest city in Texas without a four-lane divided highway connecting to an interstate highway within the state. However, those traveling north of the city can go into the Midwest on a four-lane thoroughfare via US 271 across the Red River into Oklahoma, and then the Indian Nation Turnpike from Hugo to Interstate 40 at Henryetta, which in turn continues as a free four-lane highway via US 75 to Tulsa.

Paris is served by two taxicab companies. Cox Field provides general aviation services.

Attractions

- Pat Mayse Lake

- Beaver's Bend Resort Park (Oklahoma)

- Evergreen Cemetery – Located on the south side of town, there are over 50,000 people interred. This is the site of a noted 12-foot (3.7 m) tall "Jesus with cowboy boots" statue and grave marker, as well as the resting place of banker/philanthropist William J. McDonald, Confederate General/U.S. Senator Sam Bell Maxey, rancher Pitts Chisum, and cotton magnate John J. Culbertson. Pitts Chisum's more famous brother, John Chisum, is also buried in the city.

- Sam Bell Maxey House – Maxey was a Confederate general and 2 time US Senator.

- Paris Eiffel Tower

- On October 4, 1955, early in his career, Elvis Presley performed at the Boys Club Gymnasium at 1530 1st Street Northeast in Paris as a member of the Louisiana Hayride Jamboree tour.

- Lamar County Historical Museum

Notable people

- Duane Allen, member of the Oak Ridge Boys

- Tyler Bryant, member of Tyler Bryant & the Shakedown

- Tia Ballard, actress for Funimation Entertainment

- Charles Baxter, physician, attended President Kennedy after he was fatally shot

- Raymond Berry, professional football Hall of Famer

- John Chisum, cattle baron

- Marsha Farney, Republican member of the Texas House of Representatives from Williamson County; reared in Paris, graduated from Paris Junior College, and taught school in Paris in 1990s

- Bobby Jack Floyd, National Football League (NFL) fullback

- Charles R. Floyd, three-term Democratic state senator; pioneer of the Texas farm-to-market road system and an original founder of Paris Junior College

- Cas Haley, singer/musician, NBC's season two of America's Got Talent runner-up

- Al Haynes, commercial airline pilot, captain during the United Airlines Flight 232 crash

- William Henry Huddle, Texas Capitol artist

- Charlie Jackson, NFL football player

- Frank Jackson, NFL football player

- General John P. Jumper, Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force from 2001 to 2005

- Richard Gordon Kendall (1933–2008) self-taught outsider folk artist

- Beverly Leech, actress, portrayed Kate Monday on Mathnet

- Samuel Bell Maxey, United States Senator and Confederate Major General

- Gordon McLendon, pioneer radio broadcaster and founder of the Liberty Broadcasting System

- Jay Hunter Morris, operatic tenor

- John Morris, actor

- John Osteen, pastor

- Dave Philley, professional baseball player and holder of five MLB records

- Bass Reeves, the first black deputy U.S. marshal to serve west of the Mississippi River, was based in Paris for four years in the late 19th century.

- Admiral James O. Richardson, United States Navy Fleet Commander 1940–1941

- Eddie Robinson, professional baseball player, four-time All-Star and Texas Rangers executive

- Augusta Rucker, medical doctor, zoologist, public health lecturer

- Jack Russell, professional baseball player and first relief pitcher selected to a Major League Baseball All-Star Game

- Leslie Satcher, country music recording artist

- William Scott Scudder, Major League Baseball pitcher

- Gene Stallings, Alabama head coach 1990-1996

- Steven H. Tallant, president of Texas A&M University-Kingsville

- Starke Taylor, mayor of Dallas and businessman

- Shangela Laquifa Wadley, comedian, reality television personality, and drag performer

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Physiographic Regions". Tapestry.usgs.gov. April 17, 2003. Archived from the original on May 15, 2006. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- John Sayles; Henry Sales (1889). Revised Civil Statutes and Laws Passed by the 16th, 17th, 18th, 19th, & 20th Legislatures of the State of Texas. 1. Gilbert Book Company. p. 281. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- "Texas Almanac: Secession and the Civil War". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- Tx State Historical Commission (1978). "The Paris Fire of 1916 – Texas State Historical Marker".

- Campbell Roberts (February 10, 2015). "History of Lynchings in the South Documents Nearly 4,000 Names". The New York Times. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- "Largent v. State of Tex". U.S. Supreme Court. Retrieved January 7, 2018 – via FindLaw.

- "Union Station - Paris, Texas - Train Stations/Depots on Waymarking.com". www.waymarking.com.

- Tx State Historical Commission (1984). "Scott Mansion – Texas State Historical Marker".

- Camp Maxey, globalsecurity.org.

- The New Rating Guide to Life in America's Small Cities. Prometheus Books. 1997. ISBN 978-1573921701. cited in Day Trips from Dallas/Fort Worth: Getaway Ideas for the Local Traveler. Day Trips. GPP Travel. 2010. p. 42. ISBN 978-0762757077. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- Howard Witt (February 1, 2009). "Paris, Texas, race relations dialogue turns into dispute". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- Gretel C. Kovach; Ariel Campo–Flores (July 27, 2009). "The turbulent racial history of Paris, Texas". Newsweek, via Anderson Cooper 360°. CNN. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- Howard Witt (March 12, 2007). "To some in Paris, sinister past is back". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- Richard Abshire (December 4, 2008). "Justice Department community dialogue on race set for Paris, Texas". Crime Blog. Dallas Morning News. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- Jeff Carlton (August 21, 2009). "Riot Police Storm Texas Town After Black, White Protesters Clash Over Dragging Death". Huffington Post. Retrieved May 3, 2015.

- James C. McKinley Jr. (February 14, 2009). "Killing Stirs Racial Unease in Texas". New York Times. Retrieved May 3, 2015.

- Howard Witt (March 31, 2007). "Girl in prison for shove gets released early". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- Howard Witt (February 25, 2009). "Racism bedevils Texas town". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- Alejandra Cancino (February 10, 2015). "Sara Lee discriminated against black employees, attorneys say". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 3, 2015.

- "Workers Targets of Racist Behavior at Sara Lee Plant: EEOC". NBC Channel 5 Dallas–Fort Worth. February 10, 2015. Retrieved May 3, 2015.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- Boyd, Matthew. "Paris officers remember deadly tornado of 1982". Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- "Weatherbase". Weatherbase. Retrieved October 4, 2018.

- "PARIS". Texas Almanac. November 22, 2010. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Major employers". parisedc.com. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 2, 2016. Retrieved May 12, 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Paris Public Library - Paris". www.paristexas.gov.

- Parole Division Region I Archived September 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice.

- Post Office Location – Paris Archived May 7, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

External links

![]()

- "Paris (Texas)". Encyclopædia Britannica. 20 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 823.

- . . 1914.

- City of Paris

- Paris Texas Event Calendar

- Lamar County Historical Society

- Lamar County Courthouse

- Handbook of Texas Online entry

- Paris Texas information – Lamar County Station