Pareiasaur

Pareiasaurs (meaning "cheek lizards") were a clade of parareptiles comprising the family Pareiasauridae. They were large herbivores that flourished during the Permian period. Parareptiles form a sister clade to reptiles and birds.

| Pareiasaur | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeleton of Scutosaurus karpinskii in the American Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | †Parareptilia |

| Order: | †Procolophonomorpha |

| Node: | †Ankyramorpha |

| Clade: | †Procolophonia |

| Clade: | †Pareiasauromorpha |

| Superfamily: | †Pareiasauroidea |

| Clade: | †Pareiasauria Seeley, 1888 |

| Genera | |

| |

Description

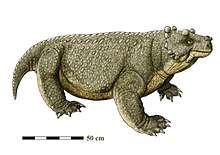

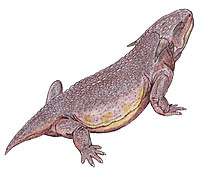

Pareiasaurs ranged in size from 60 to 300 centimetres (2.0 to 9.8 ft) long, and may have weighed up to 600 kilograms (1,300 lb). They were stocky, with short tails, small heads, robust limbs, and broad feet. The cow-sized species Bunostegos, which lived 260 million years ago, is the earliest known example of a tetrapod with a fully erect posture as its legs were positioned directly under its body.[1] Pareiasaurs were protected by bony scutes called osteoderms that were set into the skin. Their heavy skulls were ornamented with multiple knobs and ridges. The leaf-shaped multi-cusped teeth resemble those of iguanas, caseids, and other reptilian herbivores. This dentition, together with the deep body, which may have housed an extensive digestive tract, are evidence of a herbivorous diet. Most authors have assumed a terrestrial lifestyle for pareiasaurs, but bone microanatomy suggests a more aquatic, plausibly amphibious lifestyle.[2]

Evolutionary history

Pareiasaurs appear very suddenly in the fossil record. It is clear that these animals are parareptiles.[3][4] As such, they are closely related to Nycteroleterids.[5] Like Rhipaeosaurs, they may have filled the large herbivore niche (or guild) that had been occupied early in the Permian period by the Caseid pelycosaurs and, before them, the Diadectid amphibians and Edaphosaur reptiles. They are much larger than the diadectids, more similar to the giant caseid pelycosaur Cotylorhynchus. Although the last Pareiasaurs were no larger than the first types (indeed, many of the last ones became smaller), there was a definite tendency towards increased armour as the group developed.

Classification

Some paleontologists considered that pareiasaurs were direct ancestors of modern turtles. Pareiasaur skulls have several turtle-like features, and in some species the scutes have developed into bony plates, possibly the precursors of a turtle shell.[6] Jalil and Janvier, in a large analysis of pareiasaur relationships, also found turtles to be close relatives of the "dwarf" pareiasaurs, such as Pumiliopareia.[7] However, the discovery of Pappochelys argues against a potential pareisaurian relationship to turtles.[8]

Associated clades

Hallucicrania (Lee 1995): This clade was coined by MSY Lee for Lanthanosuchidae + (Pareiasauridae + Testudines). Lee's pareiasaur hypothesis has become untenable due to the diapsid features of the stem turtle Pappochelys and the potential testudinatan nature of Eunotosaurus. Recent cladistic analyses reveal that lanthanosuchids have a much more basal position in the Procolophonomorpha, and that the nearest sister taxon to the pareiasaurs are the rather unexceptional and conventional looking nycteroleterids (Müller & Tsuji 2007, Lyson et al. 2010) the two being united in the clade Pareiasauromorpha (Tsuji et al. 2012).

Pareiasauroidea (Nopcsa, 1928): This clade (as opposed to the superfamily or suborder Pareiasauroidea) was used by Lee (1995) for Pareiasauridae + Sclerosaurus. More recent cladistic studies place Sclerosaurus in the procolophonid subfamily Leptopleuroninae (Cisneros 2006, Sues & Reisz 2008), which means the similarities with pareiasaurs are the result of convergences.

Pareiasauria (Seeley, 1988): If neither Lanthanosuchids or Testudines are included in the clade, the Pareiasauria only contains the monophyletic family Pareiasauridae. It's a traditional linnaean term.

Phylogeny

Below is a cladogram from Tsuji et al. (2013):[9]

| Pareiasauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Pre-reptile may be earliest known to walk upright on all fours

- Kriloff, A.; Germain, D.; Canoville, A.; Vincent, P.; Sache, M.; Laurin, M. (2008). "Evolution of bone microanatomy of the tetrapod tibia and its use in palaeobiological inference". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 21 (3): 807–826. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01512.x. PMID 18312321.

- Gauthier, J., Kluge, A.G. and Rowe, T. (1988). "The early evolution of the Amniota." Pp. 103–155 in Benton, M.J. (ed.), The phylogeny and classification of the tetrapods, Volume 1: amphibians, reptiles, birds. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Laurin, M.; Reisz, R.R. (1995). "A reevaluation of early amniote phylogeny". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 113 (2): 165–223. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1995.tb00932.x.

- LEE, M. S. Y. (1995). "Historical burden in systematics and the interrelationships of 'parareptiles'". Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 70: 459–547. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185x.1995.tb01197.x.

- Lee, M.S.Y. (1997). "Pareiasaur phylogeny and the origin of turtles". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 120 (3): 197–280. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1997.tb01279.x.

- Jalil, N.-E.; Janvier, P. (2005). "Les pareiasaures (Amniota, Parareptilia) du Permien supérieur du Bassin d'Argana, Maroc". Geodiversitas. 27 (1): 35–132.

- Schoch, Rainer R.; Sues, Hans-Dieter (2015). "A Middle Triassic stem-turtle and the evolution of the turtle body plan". Nature. 523 (7562): 584–587. doi:10.1038/nature14472. PMID 26106865.

- Tsuji, L. A.; Sidor, C. A.; Steyer, J. - S. B.; Smith, R. M. H.; Tabor, N. J.; Ide, O. (2013). "The vertebrate fauna of the Upper Permian of Niger—VII. Cranial anatomy and relationships of Bunostegos akokanensis (Pareiasauria)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 33 (4): 747–763. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.739537.

- Carroll, R. L., (1988), Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution, W.H. Freeman & Co. New York, p. 205

- Kuhn, O, 1969, Cotylosauria, part 6 of Handbuch der Palaoherpetologie (Encyclopedia of Palaeoherpetology), Gustav Fischer Verlag, Stuttgart & Portland

- Laurin, M. (1996), "Introduction to Pareiasauria - An Upper Permian group of Anapsids"

- Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (24 June 2013). "Pareiasaur: Bumpy beast was a desert dweller". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

External links

- Hallucicrania - Pareiasauriformes at Mikko's Phylogeny Archive

- Anapsida: Hallucicrania at Palaeos