Pappochelys

Pappochelys (παπποχέλυς [πάππος (grandfather) + χέλυς (turtle)] meaning "grandfather turtle" in Greek) is an extinct genus of diapsid reptile closely related to turtles. The genus contains only one species, Pappochelys rosinae, from the Middle Triassic of Germany, which was named by paleontologists Rainer Schoch and Hans-Dieter Sues in 2015. The discovery of Pappochelys provides strong support for the placement of turtles within Diapsida, a hypothesis that has long been suggested by molecular data, but never previously by the fossil record. It is morphologically intermediate between the definite stem-turtle Odontochelys from the Late Triassic of China and Eunotosaurus, a reptile from the Middle Permian of South Africa.[1][2]

| Pappochelys | |

|---|---|

| |

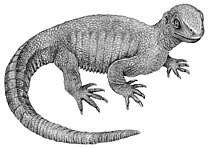

| The holotype specimen of Pappochelys | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Pantestudines |

| Genus: | †Pappochelys Schoch & Sues 2015 |

| Type species | |

| †Pappochelys rosinae | |

Description

Pappochelys had a wide body, small skull, and a long tail that makes up about half of the total body length, which is up to 20 centimetres (8 in). The skull is pointed with large eye sockets. Several turtle-like features are present, including expanded ribs and gastralia that seem to be precursors of a shell. As is the case in Eunotosaurus, each rib is flattened into a broad blade-like structure with bumps and ridges covering its outer surface and a ridge running down its inner surface, forming a T-shape in cross section. The gastralia (rib-like bones covering the abdomen) are tightly packed and occasionally fused together, forming a structure similar to the plastron of turtles. Unlike turtles, Pappochelys has teeth in its jaws and two pairs of holes in the back of the skull called temporal fenestrae. The presence of two pairs of fenestrae make the skull of Pappochelys diapsid, as opposed to the anapsid skulls of turtles that lack any temporal fenestrae.[1]

Discovery

Fossils of Pappochelys come from a rock group in Germany called the Lower Keuper, which dates to the Ladinian stage of the Middle Triassic, approximately 240 million years ago (Ma), and are restricted to a 5 to 15 centimetres (2 to 6 in) layer of organic-rich claystone in an outcrop of the Erfurt Formation in the town of Vellberg. Paleontologists have studied the Lower Keuper extensively since the early nineteenth century and the claystone layer has been subject to intensive fossil collecting since 1985, yet it was not until 2006 that the first fossils of Pappochelys were found. Since then, excavations by the Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart have uncovered 20 specimens of Pappochelys representing most of the skeleton.[3]

Relationship to turtles

The placement of turtles on the reptile evolutionary tree has been a point of contention in the past few decades because of a disagreement between morphological and molecular data. Based on anatomical data alone, turtles appear to fall within Parareptilia, which is a basal clade or evolutionary group within Sauropsida (Sauropsida is the reptile clade). Parareptiles are generally characterized by the lack of temporal openings in their skull (but now most of them are known to have at least a lower temporal fenestra,[4][5][6][7]) and lie outside the main group of reptiles, Diapsida, which includes all other living sauropsids (lizards, snakes, crocodilians, and birds) and is characterized by two pairs of temporal openings. In contrast, molecular data suggests that turtles lie within Diapsida, either as a subset of the Lepidosauromorpha (which includes lizards and snakes)—supported by one microRNA analysis—or the clade Archosauromorpha (which includes crocodilians and birds)[1]—supported by almost all molecular analyses.

Of the reptiles that most closely resemble Pappochelys, Eunotosaurus was originally classified as a parareptile and Odontochelys has always been classified as a stem-turtle (stem-turtles are taxa more closely related to turtles than they are to any other living reptile group, but are not themselves turtles). Since Eunotosaurus possesses both turtle-like and parareptile-like features, it has often been used to justify a parareptilian ancestry for turtles. The discovery of Pappochelys, which is clearly a diapsid, provides the first strong evidence from the fossil record that turtles belong within Diapsida. In 2015, Schoch and Sues incorporated Pappochelys, Eunotosaurus, and Odontochelys into a phylogenetic analysis along with parareptiles, turtles, and many other reptilian taxa to elucidate their relationships. Their analysis found support for a diapsid clade containing Eunotosaurus, Pappochelys, Odontochelys, and turtles, and placed this clade within Lepidosauromorpha. This clade was only distantly related to parareptiles, which was recovered as the most basal group within Sauropsida. Unlike previous morphology-based phylogenies (hypotheses of evolutionary relationships), Schoch and Sues's phylogeny was in agreement with molecular data. Below is a cladogram or evolutionary tree showing the results of their analysis, with stem-turtles denoted by the green bracket:[1]

|

stem-turtles |

Paleobiology

The claystone bed in which fossils of Pappochelys were found was likely deposited in a lake setting, suggesting that Pappochelys may have been semi-aquatic like modern turtles. Although Pappochelys lacked a fully formed shell like modern turtles, its thickened bones may have helped reduce the body's buoyancy, making it a more adept swimmer.[1] However, otherwise the anatomy has few adaptations for swimming. In addition, a histological study found that its limb bones had a thick outer wall and small, open (rather than spongy) medullary cavity, like only a few aquatic reptiles and completely unlike modern aquatic turtles. These features have also been recorded in terrestrial reptiles such as the modern lizard Sceloporus and Eunotosaurus, another genus of pantestudine with burrowing adaptations. This may indicate that Pappochelys had a burrowing or modestly aquatic lifestyle, rather than a fully aquatic one.[8]

References

- Schoch, Rainer R.; Sues, Hans-Dieter (24 June 2015). "A Middle Triassic stem-turtle and the evolution of the turtle body plan". Nature. 523 (7562): 584–587. doi:10.1038/nature14472. PMID 26106865.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kaplan, Sarah (June 25, 2015). "How the turtle got its shell, a not-so 'Just So' story". Morning Mix. Washington Post.

- Schoch, R. R.; Sues, H.-D. (2015). "A Middle Triassic stem-turtle and the evolution of the turtle body plan: Supplementary Information" (PDF). Nature. 523 (7562): 584–587. doi:10.1038/nature14472. PMID 26106865.

- Cisneros, Juan C.; et al. (2004). "A procolophonoid reptile with temporal fenestration from the Middle Triassic of Brazil". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 271 (1547): 1541–1546. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2748. PMC 1691751. PMID 15306328.

- Reisz, Robert R.; et al. (2007). "The cranial osteology of Belebey vegrandis (Parareptilia: Bolosauridae), from the Middle Permian of Russia, and its bearing on reptilian evolution". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 151 (1): 191–214. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00312.x.

- Piñeiro, Graciela; et al. (2012). "Cranial morphology of the Early Permian mesosaurid Mesosaurus tenuidens and the evolution of the lower temporal fenestration reassessed". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 11 (5): 379–391. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2012.02.001.

- MacDougall; Reisz (2014). "The first record of a nyctiphruretid parareptile from the Early Permian of North America, with a discussion of parareptilian temporal fenestration". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 172 (3): 616–630. doi:10.1111/zoj.12180.

- Schoch, Rainer R.; Klein, Nicole; Scheyer, Torsten M.; Sues, Hans-Dieter (2019-07-18). "Microanatomy of the stem-turtle Pappochelys rosinae indicates a predominantly fossorial mode of life and clarifies early steps in the evolution of the shell". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 10430. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-46762-z. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6639533. PMID 31320733.

External links