Cotylorhynchus

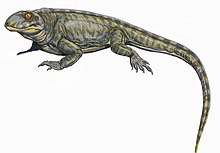

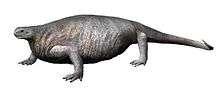

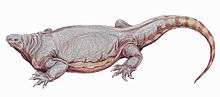

Cotylorhynchus is an extinct genus of very large synapsids that lived in the southern part of what is now North America during the Early Permian period.[1] It is the best known member of the synapsid clade Caseidae, usually considered the largest terrestrial vertebrates of the Early Permian,[2] though they were possibly aquatic.[3]

| Cotylorhynchus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton of C. romeri | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | †Caseasauria |

| Family: | †Caseidae |

| Genus: | †Cotylorhynchus Stovall, 1937 |

| Type species | |

| †Cotylorhynchus romeri Stovall, 1937 | |

| Species | |

| |

Description

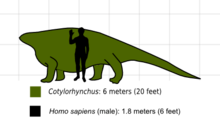

Cotylorhynchus was a heavily built animal with a disproportionately small head and a huge barrel-shaped body. While the smaller species, C. romeri, only grew to lengths of 4.5 - 4.8m (14.7 - 15.7ft), the larger species, C. hancocki, stretched 6m (20ft) long. making it one of the largest synapsids of the early Permian.

Their skulls are distinctive in the presence of large temporal openings and very large nostril openings, which could have been utilized for better breathing or may have housed some sort of sensory or moisture conserving organ. Also they featured large pineal openings and a snout or upper jaw that overhangs the row of teeth to form a projecting rostrum. Rounded deep pits and possibly large depressions were present on the outer surface of the skull. Their teeth were very similar to those of iguanas with posterior marginal teeth that bore a longitudinal row of cusps.

Their skeletal features included a massive scapulocoracoid, humeri with large flared ends, stout forearm bones and broad, robust hands that had large claws. Certain features of their hands indicate that they were paddle-like in shape and structure, being used to swim in a manner much similar to that of modern turtles.[4]

Their digits were believed to have a considerable range of motion and large retractor processes on the ventral surfaces of the unguals allowed them to flex their claws with powerful motions. Also, the articulatory surfaces of their phalanges were oblique to the bone's long axis rather than perpendicular to it. This allowed for much more surface area for the flexor muscles.

Cotylorhynchus shows evidence indicative of a diaphragm. Unlike that of modern mammals it was probably weak and necessitating support from other muscle groups, a deficiency exacerbated by its aquatic habits.[4]

Discovery

Cotylorhynchus were considered a part of the first wave of amniote diversity. There have been three species of Cotylorhynchus discovered: C. hancocki, C. romeri[5] and C. bransoni. C. hancocki is believed to be a descendant of the slightly smaller C. romeri.

- Various skeletal parts of C. romeri have been found around central Oklahoma[6] in parts of Cleveland County.

- Parts of C. hancocki have been found in northern Texas in Hardeman and Knox counties.

- C. bransoni specimens have been uncovered in Kingfisher and Blaine Counties of central-northwest Oklahoma.

Classification

Cotylorhynchus belongs to the family Caseidae, a family of massively built synapsids with small heads and barrel-like bodies. It was a derived member of Caseidae. It is a sister taxon of Angelosaurus.

Below is a cladogram by Maddin et al. in 2008.[7]

| Caseasauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Maddin, Hillary C.; Sidor, Christian A.; Reisz, Robert R. (2008). "Cranial Anatomy of Ennatosaurus tecton (Synapsid: Caseidae) From the Middle Permian of Russia and the Evolutionary Relationships of Caseidae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (1): 161. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[160:CAOETS]2.0.CO;2.

- "Caseasauria". Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- Lambertz, M.; Shelton, C.D.; Spindler, F.; Perry, S.F. (2016). "A caseian point for the evolution of a diaphragm homologue among the earliest synapsids". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1385 (1): 3–20. doi:10.1111/nyas.13264. PMID 27859325.

- Markus Lambertz et al, A caseian point for the evolution of a diaphragm homologue among the earliest synapsids, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences (2016). DOI: 10.1111/nyas.13264

- Stovall, J. Willis; Price, Llewellyn; Romer, Alfred (1966). "The Postcranial Skeleton of the Giant Permian Pelycosaur Cotylorhynchus romeri" (PDF). Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. 135 (1). Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- "Fossil Evidence Permian". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- Maddin; et al. (2008). "Cranial anatomy of "Ennatosaurus tecton" (Synapsida: Caseidae) from the middle permian of russia and the evolutionary relationships of Caseidae" (PDF): 173. Retrieved 26 November 2013. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)