Leptopleuron

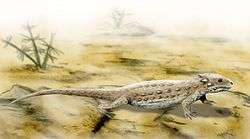

Leptopleuron is an extinct genus of procolophonid that lived in the dry lands during the late Triassic in Elgin of northern Scotland and was the first to be included in the clade of Procolophonidae.[1] First described by English paleontologist and biologist Sir Richard Owen, Leptopleuron is derived from two Greek bases, leptos for "slender" and pleuron for "rib," describing it as having slender ribs. The fossil is also known by a second name, Telerpeton, which is derived from the Greek bases tele for "far off" and herpeton for "reptile."[2] In Scotland, Leptopleuron was found specifically in the Lossiemouth Sandstone Formation.[3][4] The yellow sandstone it was located in was poorly lithified with wind coming from the southwest. The environment is also described to consist of barchan dunes due to the winds, ranging up to 20 m tall that spread during dry phases into flood plains.[3] Procolophonoids such as Leptopleuron were considered an essential addition to the terrestrial ecosystem during the Triassic.[5]

| Leptopleuron | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | †Parareptilia |

| Order: | †Procolophonomorpha |

| Family: | †Procolophonidae |

| Tribe: | †Leptopleuronini |

| Genus: | †Leptopleuron Owen, 1851 |

| Type species | |

| †Leptopleuron lacertinum Owen, 1851 | |

| Synonyms | |

Discovery and history

_(14597292740).jpg)

Discovered near Elgin, northern Scotland, from the Lossiemouth Formation in 1851, the fossil was examined and named Leptopleuron by Richard Owen. The reptilian fossil was initially evidence against progressionism, supporting the words of Charles Lyell, but with discussion was later accepted from the Triassic and for progressionism in 1860 after he became a progressionist. Controversy arose later when news broke out that the discoverer asked English paleontologist Gideon Mantell to make a lengthier description of the fossil, calling it Telerpeton. The general consensus that Owen produced a description of the fossil with hostility toward both Lyell and Mantell was also an issue. However, later analysis found that Mantell only produced a description as requested by Lyell, knowing that Owen was composing his own at the same time. Leptopleuron is the most accepted term for the reptile as Owen published before Mantell and made the most accurate interpretations.[4]

Description

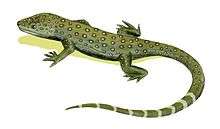

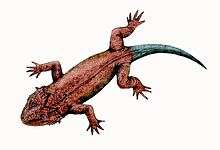

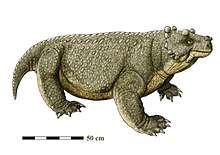

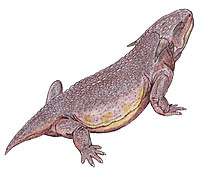

Leptopleuron was a small, lizard-like animal of 270 mm that possessed a long tail[6] as well as gastralia in contrast to Sclerosaurus,[7] and a slight triangular depression on its jugal.[8] As a reptile, five metatarsals were observed with lengths of roughly 8 mm with unknown values for some.[6] In terms of its dentary, towards the posterior end, the ramus is notably deep.[9] Its sacral ribs do not attach to the vertebrae after reconstruction of the fossil.[6] The neural spines of Leptopleuron, in particular, lean backwards as comparable and observed in Anomoiodon liliensterni and the genus Kapes.[10] Acrodont dentition is evident in leptopleurons as well.[11]

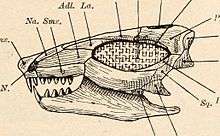

Osteology of the skull

After reconstruction, the skull reached 55 mm long. The width of the skull was as long as the length of the skull when ignoring the quadratojugal horns as well. Some features of Leptopleuron include the size of its frontals. In contrast to other taxa, the width in the middle of the orbits are not the same as the width of its frontals in the anterior segment. Leptopleuron demonstrates a narrower anterior portion instead. No septomaxilla was observed, but the external naris is oval and immense in size. The maxilla contained five teeth with a significant difference for the tooth row as in contrast to Hypsognathus, the tooth row ended around the anterior region of the orbitotemporal opening. The prefrontal of Leptopleuron is seen to have dorsal exposure in the center of the lacrimal and frontal bones with the anterior edge enveloped by the nasals. The lacrimal is extremely concave at the whole orbital region, creating an immense depression heading toward the snout interior. This depression is known to enter the posterior of the orbitonasal canal after analysis. The parietal occupies the space for the postfrontal as this feature is absent in Leptopleuron. The pineal foramen is large and between the parietals and frontals. Its orbitotemporal openings are not relatively long and are similar to those of Procolophon. The jugal is also known to come into contact with the posterolateral extension of the nasal at its anterior end and barely touches the postorbital. The two spines of the quadratojugal are both flattened dorsoventrally, contain evident grooves, and are roughly the same size. Leptopleuron does not have a quadrate foramen as well, but the center part of the quadrate is stretched transversely. Notably, this bone is seen to connect with the pterygoid at the quadrate flange. Leptopleuron has also been identified to have vomerine dentition with short and long pairs of fangs. The tail fangs are at the anterior end of the vomer while the posterior end holds the short fangs. The palatine can only be seen in dorsal view and not in palatal view.[6]

The braincase

Sharing similarities with other procolophonids, the braincase of Leptopleuron consists of a relatively long basisphenoid that covers the front part of the basioccipital. Other apomorphies include a tripartite occipital condyle and a metotic foramen exposed anteriorly and unwalled by bone. Taking up the bottom half of the tripartite occipital condyle, the basioccipital is easily identified for having a large anterior portion. On the other hand, the exoccipitals are at the dorsolateral portion of the condyle and its arch-like supraoccipital forms the most dorsal edge of the foramen magnum as it is integrated with the prootic located anterolaterally. On the supraoccipital, a slight groove can be seen at each anteroventral extremity, particularly at the dorsolateral side. Leptopleuron is also characterized by its opisthotic having no foramen on the ventral ramus, specifically for nerve IX. The opisthotic is identified by a short transverse ridge that flanks a relatively deep and crescent moon-like notch ventrally. As for the prootic, the anteroventral process extends out into a free-standing distal plate rounded at the anterior. Characteristic of Leptopleuron as well is its extremely tiny stapes with a cone-like and obtusely sub-triangular footplate in lateral view.[5] It was also known that its opisthotic and basioccipital did not come into contact with each other.[12]

Paleobiology

Diet

Based on its dentition, Leptopleuron likely fed on coarse and fibrous vegetation or hard-shelled invertebrates as it possessed two-cusped marginal teeth that were labio-lingually spread out. Analysis also suggests vegetation in its diet as a procolophonid because of its trunks being larger and wider than those belonging to Owenettidae, indicated by their slimmer body shape.[6]

Burrowing

The horned triangular head of Leptopleuron, as well as an overbite comparable to the horned sand lizard, were evident of its burrowing lifestyle. With an overbite aiding in less ingestion of dirt, along with spade-like unguals and strong limbs for efficient digging, Leptopleuron was likened to today's burrowers of Phrynosoma, a genus consisting of horned lizards. Skepticism remains, however, due to both its manus and pes having slender phalanges and unguals compared to Procolophon, which is characteristically inefficient for dredging through dirt.[6]

See also

References

- Fraser, Nicholas; Irmis, Randall; Elliott, David (6 March 2005). "A PROCOLOPHONID (PARAREPTILIA) FROM THE OWL ROCK MEMBER, CHINLE FORMATION OF UTAH, USA". Palaeontologia Electronica. 8 (1): 1–7. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- "Genus: Leptopleuron OWEN, 1851". Paleofile. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- "Lossiemouth West & East Quarries, Elgin (Triassic to of the United Kingdom)". The Paleobiology Database. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- Benton, Michael (1982). "Progressionism in the 1850s: Lyell, Owen, Mantell and the Elgin fossil reptile Leptopleuron (Telerpeton)". Archives of Natural History. 11 (1): 123–136. doi:10.3366/anh.1982.11.1.123.

- Spencer, Patrick (2000). "The braincase structure of Leptopleuron lacertinum Owen (Parareptilia: Procolophonidae)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 20 (1): 21–30. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2000)020[0021:TBSOLL]2.0.CO;2.

- Säilä, Laura (27 April 2010). "Osteology of Leptopleuron lacertinum Owen, a procolophonoid parareptile from the Upper Triassic of Scotland, with remarks on ontogeny, ecology and affinities". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 101 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1017/S1755691010009138.

- Sues 1, Hans-Dieter; Reisz, Robert (December 2008). "Anatomy and phylogenetic relationships of Sclerosaurus armatus(Amniota: Parareptilia) from the Buntsandstein (Triassic) of Europe" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (4): 1031–1042. doi:10.1671/0272-4634-28.4.1031. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- Sues, Hans-Dieter; Olsen, Paul; Scott, Diane; Spencer, Patrick (June 2000). "Cranial osteology of Hypsognathus fenneri, a latest Triassic procolophonid reptile from the Newark Supergroup of eastern North America" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 20 (2): 275–284. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2000)020[0275:coohfa]2.0.co;2. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- Sues, Hans-Dieter; Baird, Donald (September 1998). "Procolophonidae (Reptilia: Parareptilia) from the Upper Triassic Wolfville Formation of Nova Scotia, Canada". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 18 (3): 525–532. doi:10.1080/02724634.1998.10011079.

- Säilä, Laura (March 2008). "The Osteology and Affinities of Anomoiodon liliensterni, A Procolophonid Reptile from the Lower Triassic Bundsandstein of Germany". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (4): 1199–1205. doi:10.1671/0272-4634-28.4.1199.

- Modesto, Sean; Macdougall, Mark (March 2011). "New Information on the Skull of the Early Triassic Parareptile Sauropareion anoplus, with a Discussion of Tooth Attachment and Replacement in Procolophonids". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (2): 270–278. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.549436.

- Maisch, Michael; Matzke, Andreas (September 2006). "The braincase of Phantomosaurus neubigi(Sander, 1997), an unusual ichthyosaur from the Middle Triassic of Germany". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (3): 598–607. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[598:tbopns]2.0.co;2.