Parareptilia

Parareptilia ("at the side of reptiles") is a subclass or clade of reptiles which is variously defined as an extinct group of primitive anapsids, or a more cladistically correct alternative to Anapsida. Whether the term is valid depends on the phylogenetic position of turtles, whose relationships to other reptilian groups are still uncertain. The parareptiles lived from late Carboniferous till the end of the Permian, except from one group, the Procolophonoidea, which are the only parareptiles known to have survived the end-Permian extinction, and didn't disappear until the late Triassic.[2]

| Parareptiles | |

|---|---|

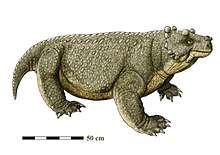

| Skeleton of a parareptile (Bradysaurus baini) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | †Parareptilia Olson, 1947 |

| Orders | |

History of classification

The name Parareptilia was coined by Olson in 1947 to refer to an extinct group of Paleozoic reptiles, as opposed to the rest of the reptiles or Eureptilia ("true reptiles").

The name fell into disuse until it was revived by cladistic studies, to refer to those anapsids that were thought to be unrelated to turtles. Gauthier et al. 1988 provided the first phylogenetic definitions for the names of many amniote taxa and argued that captorhinids and turtles were sister groups, constituting the clade Anapsida (in a much more limited context than the definition given by Romer in 1967). A name had to be found for various Permian and Triassic reptiles no longer included in the anapsids, and "parareptiles" was chosen. However, they did not feel confident enough to erect Parareptilia as a formal taxon. Their cladogram was as follows:

| Amniota |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Laurin and Reisz 1995 found a different cladogram, in which Reptilia were divided into Parareptilia (now a formal taxon they defined as "Testudines and all amniotes more closely related to them than to diapsids.") and Eureptilia. Captorhinidae was transferred to Eureptilia, and Parareptilia included both early anapsid reptiles and turtles. The mesosaurs were placed outside both groups, as the sister group to the reptiles (but still sauropsids). The traditional group Anapsida was rejected as paraphyletic. This gave the following result:

| Amniota |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In contrast, Rieppel, 1994, 1995; Rieppel & deBraga, 1996; and deBraga & Rieppel, 1997 argued that turtles are actually related to the sauropterygians, and are diapsids. The diapsid affinities of turtles have been supported by molecular phylogenies (e.g. Zardoya and Meyer 1998; Iwabe et al., 2004; Roos et al., 2007; Katsu et al., 2010). The first genome-wide phylogenetic analysis was completed by Wang et al. (2013). Using the draft genomes of Chelonia mydas and Pelodiscus sinensis, the team used the largest turtle data set to date in their analysis and concluded that turtles are likely a sister group of crocodilians and birds (Archosauria).[3] This placement within the diapsids suggests that the turtle lineage lost diapsid skull characteristics as it now possesses an anapsid skull. This would make Parareptilia a totally extinct group with skull features that coincidentally resemble those of turtles.

The cladogram below follows an analysis by M.S. Lee, in 2013.[4]

| Amniota |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Arjan Mann; Emily J. McDaniel; Emily R. McColville; Hillary C. Maddin (2019). "Carbonodraco lundi gen et sp. nov., the oldest parareptile, from Linton, Ohio, and new insights into the early radiation of reptiles". Royal Society Open Science. 6 (11): Article ID 191191. doi:10.1098/rsos.191191. PMC 6894558. PMID 31827854.

- Palaeobiology of Triassic procolophonids, inferred from bone microstructure

- Wang, Zhuo; Pascual-Anaya, J; Zadissa, A; Li, W; Niimura, Y; Huang, Z; Li, C; White, S; Xiong, Z; Fang, D; Wang, B; Ming, Y; Chen, Y; Zheng, Y; Kuraku, S; Pignatelli, M; Herrero, J; Beal, K; Nozawa, M; Li, Q; Wang, J; Zhang, H; Yu, L; Shigenobu, S; Wang, J; Liu, J; Flicek, P; Searle, S; Wang, J; et al. (27 March 2013). "The draft genomes of soft-shell turtle and green sea turtle yield insights into the development and evolution of the turtle-specific body plan". Nature Genetics. 45 (701–706): 701–6. doi:10.1038/ng.2615. PMC 4000948. PMID 23624526.

- Lee, M. S. Y. (2013). "Turtle origins: Insights from phylogenetic retrofitting and molecular scaffolds". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 26 (12): 2729–2738. doi:10.1111/jeb.12268. PMID 24256520.

- Benton, M. J. (2000). Vertebrate Palaeontology (2nd ed.). London: Blackwell Science Ltd. ISBN 978-0-632-05614-9., 3rd ed. 2004 ISBN 0-632-05637-1

- deBraga, M.; Rieppel, O. (1997). "Reptile phylogeny and the interrelationships of turtles". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 120 (3): 281–354. doi:10.1006/zjls.1997.0079.

- deBraga, M.; Reisz, R. R. (1996). "The Early Permian reptile Acleistorhinus pteroticus and its phylogenetic position". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 16 (3): 384–395. doi:10.1080/02724634.1996.10011328.

- Gauthier, J.; A. G. Kluge; T. Rowe (1988). "The early evolution of the Amniota". In M. J. Benton (ed.). The phylogeny and classification of the tetrapods, Volume 1: amphibians, reptiles, birds. 103-155. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Iwabe, N.; Hara, Y.; Kumazawa, Y.; Shibamoto, K.; Saito, Y.; Miyata, T.; Katoh, K. (2004-12-29). "Sister group relationship of turtles to the bird-crocodilian clade revealed by nuclear DNA-coded proteins". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 22 (4): 810–813. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi075. PMID 15625185. Retrieved 2010-12-31.

- Katsu, Y.; Braun, E. L.; Guillette, L. J. Jr.; Iguchi, T.; Guillette (2010-03-17). "From reptilian phylogenomics to reptilian genomes: analyses of c-Jun and DJ-1 proto-oncogenes". Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 127 (2–4): 79–93. doi:10.1159/000297715. PMID 20234127.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Laurin, M.; Gauthier, J. A. (1996). "Phylogeny and Classification of Amniotes". at the Tree of Life Web Project.

- Laurin, M.; Reisz, R. R. (1995). "A reevaluation of early amniote phylogeny". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 113 (2): 165–223. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1995.tb00932.x. (abstract)

- Olson, E. C. (1947). "The family Diadectidae and its bearing on the classification of reptiles". Fieldiana Geology. 11: 1–53. ISSN 0096-2651.

- Rieppel, O. (1994). "Osteology of Simosaurus gaillardoti and the relationships of stem-group sauropterygia". Fieldiana Geology. 1462: 1–85. ISSN 0096-2651.

- Rieppel, O. (1995). "Studies on skeleton formation in reptiles: implications for turtle relationships". Zoology-Analysis of Complex Systems. 98: 298–308.

- Rieppel, O.; deBraga, M. (1996). "Turtles as diapsid reptiles". Nature. 384 (6608): 453–455. doi:10.1038/384453a0.

- Romer, A. S. (1967). Vertebrate Paleontology (3rd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-7167-1822-2.

- Roos, Jonas; Aggarwal, Ramesh K.; Janke, Axel (Nov 2007). "Extended mitogenomic phylogenetic analyses yield new insight into crocodylian evolution and their survival of the Cretaceous–Tertiary boundary". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 45 (2): 663–673. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.06.018. PMID 17719245.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Zardoya, R.; Meyer, A. (1998). "Complete mitochondrial genome suggests diapsid affinities of turtles" (PDF). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 95 (24): 14226–14231. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.24.14226. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 24355. PMID 9826682.

External links

- Parareptilia

- re Reptilian Subclass Parareptilia? - Dinosaur Mailing List archives

_(Varanus_griseus).png)