Greek nationalism

Greek nationalism (or Hellenic nationalism) refers to the nationalism of Greeks and Greek culture.[1] As an ideology, Greek nationalism originated and evolved in pre-modern times.[2][3][4] It became a major political movement beginning in the 18th century, which culminated in the Greek War of Independence (1821–1829) against the Ottoman Empire.[1] It became also a potent movement in Greece shortly prior to, and during World War I, when the Greeks, inspired by the Megali Idea, managed to liberate parts of Greece in the Balkan Wars and after World War I, briefly occupied the region of İzmir before it was retaken by Turkey.[1]

Greek nationalism was also the main ideology of two dictatorial regimes in Greece during the 20th century: the 4th of August Regime (1936-41) and the Greek military junta (1967-74).

Today Greek nationalism remains important in the Greco-Turkish dispute over Cyprus[1] among other disputes.

History

.jpg)

The establishment of Panhellenic sites served as an essential component in the growth and self-consciousness of Greek nationalism.[2] During the Greco-Persian Wars of the 5th century BCE, Greek nationalism was formally established though mainly as an ideology rather than a political reality since some Greek states were still allied with the Persian Empire.[3] Aristotle and Hippocrates offered a theoretical approach on the superiority of the Greek tribes.[5]

The establishment of the ancient Panhellenic Games is often seen as the first example of ethnic nationalism and view of a common heritage and identity.

When the Byzantine Empire was ruled by the Paleologi dynasty (1261–1453), a new era of Greek patriotism emerged, accompanied by a turning back to ancient Greece.[4] Some prominent personalities at the time also proposed changing the Imperial title from "basileus and autocrat of the Romans" to "Emperor of the Hellenes".[4] This enthusiasm for the glorious past constituted an element that was present in the movement that led to the creation of the modern Greek state, in 1830, after four centuries of Ottoman rule.[4]

Popular movements calling for enosis (the incorporation of disparate Greek-populated territories into a greater Greek state) resulted in the accession of Crete (1912), Ionian Islands (1864) and Dodecanese (1947). Calls for enosis were also a feature of Cypriot politics during British Rule. During the troubled interwar years, some Greek nationalists viewed Orthodox Christian Albanians, Aromanians and Bulgarians as communities that could be assimilated into the Greek nation.[6] Greek irredentism, the "Megali Idea" suffered a setback in the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922), and the Greek genocide. Since then, Greco-Turkish relations have been characterized by tension between Greek and Turkish nationalism, culminating in the Turkish invasion of Cyprus (1974).

Nationalist political parties

Nationalist parties include:

Active

- Golden Dawn (1985–)

- Greek Unity (1989–)

- Popular Orthodox Rally (2000–)

- Society – Political Party of the Successors of Kapodistrias (2008–)

- National Hope (2010–)

- United Popular Front (2011–)

- National Unity Association (2011–)

- National Front (2012–)

- Independent Greeks (2012–)

- Popular Greek Patriotic Union (2015–)

- National Unity (2016–)

- New Right (2016–)

- Greek Solution (2016–) (parliamentary)

- Greeks for the Fatherland (2020–)

Defunct

- Nationalist Party (1865–1913) (parliamentary)

- New Party (1873–1910) (parliamentary)

- Liberal Party (1910-1961) (parliamentary)

- Freethinkers' Party (1922–1936) (parliamentary)

- National Union of Greece (1927–1944)

- Greek National Socialist Party (1932–1943)

- Hellenic Socialist Patriotic Organisation (1941–1942)

- Politically Independent Alignment (1949–1951) (parliamentary)

- Greek Rally (1951–1955) (parliamentary)

- 4th of August Party (1965–1977)

- National Democratic Union (1974–1977)

- National Alignment (1977–1981)

- United Nationalist Movement (1979–1991)

- Party of Hellenism (1981–2004)

- National Political Union (1984–1996)

- Political Spring (1993–2004)

- Hellenic Front (1994–2005)

- Front Line (1999–2000)

- Patriotic Alliance (2004–2007)

Gallery

Traditional flag used from 1769 to the Greek War of Independence.

Traditional flag used from 1769 to the Greek War of Independence. Flag of the Filiki Eteria.

Flag of the Filiki Eteria. "The Arcadian Holocaust" by Giuseppe Lorenzo Gatteri; scene from the Cretan Revolt (1866–69).

"The Arcadian Holocaust" by Giuseppe Lorenzo Gatteri; scene from the Cretan Revolt (1866–69). Alexandros Koumoundouros, founder of the Nationalist Party.

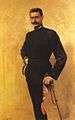

Alexandros Koumoundouros, founder of the Nationalist Party. Pavlos Melas was killed during the Macedonian Struggle.

Pavlos Melas was killed during the Macedonian Struggle.- Lorentzos Mavilis was killed during the First Balkan War.

Poster celebrating the "New Greece" after the Balkan Wars.

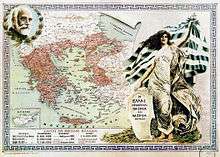

Poster celebrating the "New Greece" after the Balkan Wars. Map of "Greater Greece" after the Treaty of Sèvres, featuring Eleftherios Venizelos, when the Megali Idea seemed close to fulfillment.

Map of "Greater Greece" after the Treaty of Sèvres, featuring Eleftherios Venizelos, when the Megali Idea seemed close to fulfillment. Members of the National Organisation of Youth (EON) hail in presence of Ioannis Metaxas during the 4th of August Regime.

Members of the National Organisation of Youth (EON) hail in presence of Ioannis Metaxas during the 4th of August Regime.

See also

References

Citations

- Motyl 2001, "Greek Nationalism", pp. 201–203.

- Burckhardt 1999, p. 168: "The establishment of these Panhellenic sites, which yet remained exclusively Hellenic, was a very important element in the growth and self-consciousness of Hellenic nationalism; it was uniquely decisive in breaking down enmity between tribes, and remained the most powerful obstacle to fragmentation into mutually hostile poleis."

- Wilson 2006, "Persian Wars", pp. 555–556.

- Vasiliev 1952, p. 582.

- Hope 2007, p. 177: "Hippocrates and Aristotle both theorized the geography was responsible for the differences between peoples. Not surprisingly, both writers theorized their own Greek tribes as superior to all other human collectives."

- Çaǧaptay 2006, p. 161.

Sources

- Burckhardt, Jacob (1999) [1872]. The Greeks and Greek Civilization. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-24447-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Çaǧaptay, Soner (2006). Islam, Secularism, and Nationalism in Modern Turkey: Who is a Turk?. London and New York: Routledge (Taylor & Francis Group). ISBN 978-0-415-38458-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hope, Laura Leigh Bevis (2007). Staging the Nation/Confronting Nationalism: Theatre and Performance by Contemporary Irish and German Women. Davis, CA: University of California, Davis.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Motyl, Alexander J. (2001). Encyclopedia of Nationalism, Volume II. London and San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-054524-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vasiliev, Aleksandr Aleksandrovich (1952). History of the Byzantine Empire, 324–1453, Volume II. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-80926-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilson, Nigel (2006). Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece. New York, NY: Routledge (Taylor & Francis Group). ISBN 978-1-136-78799-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Moles, Ian N. (1969). "Nationalism and Byzantine Greece". Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies. 10 (1): 95–107.