Ottawa River timber trade

The Ottawa River timber trade, also known as the Ottawa Valley timber trade or Ottawa River lumber trade, was the nineteenth century production of wood products by Canada on areas of the Ottawa River destined for British and American markets. It was the major industry of the historical colonies of Upper Canada and Lower Canada and it created an entrepreneur known as a lumber baron. The trade in squared timber and later sawed lumber led to population growth and prosperity to communities in the Ottawa Valley, especially the city of Bytown (now Ottawa, the capital of Canada). The product was chiefly red and white pine. The industry lasted until around 1900 as both markets and supplies decreased.

| Part of a series on | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Ottawa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical individuals | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The industry came about following Napoleon's 1806 Continental Blockade in Europe causing the United Kingdom to require a new source for timber especially for its navy and shipbuilding. Later the U.K.'s application of gradually increasing preferential tariffs increased Canadian imports. The first part of the industry, the trade in squared timber lasted until about the 1850s. The transportation for the raw timber was first by means of floating down the Ottawa River, proved possible in 1806 by Philemon Wright.[1] Squared timber would be assembled into large rafts which held living quarters for men on their six week journey to Quebec City, which had large exporting facilities and easy access to the Atlantic Ocean.

The second part of the industry involved the trade of sawed lumber, and the American lumber barons and lasted chiefly from about 1850 to 1900-1910. The Reciprocity Treaty caused a shift to American markets. The source of timber in Britain changed, where its access to timber in the Baltic region was restored, and it no longer provided the protective tariffs. Entrepreneurs in the United States at that time then began to build their operations near the Ottawa River, creating some of the world's largest sawmills at the time. These men, known as lumber barons, with names such as John Rudolphus Booth and Henry Franklin Bronson created mills which contributed to the prosperity and growth of Ottawa. The sawed lumber industry benefited from transportation improvements, first the Rideau Canal[2] linking Ottawa with Kingston, Ontario on Lake Ontario, and much later railways that began to be created between Canadian cities.

Shortly after 1900, the last raft went down the Ottawa River. Supplies of pine were dwindling and there was also a decreased demand. By this time, the United Kingdom was able to resume its supply from the Baltic Region and their policies especially the reduction in protectionism of their colonies led to a decrease in markets in the U.K. Shipbuilding turned towards steel. Before 1950 many operations began to discontinue, and later many mills were completely removed and the spoiled land began to be restored in Urban Renewal policies in Ottawa. The industry had contributed greatly to population increases and economic growth of Ontario and Quebec.

Markets

Upper and Lower Canada's major industry in terms of employment and value of the product was the timber trade.[3] The largest supplier of square red and white pine to the British market originated from the Ottawa River[3] and the Ottawa Valley had "rich red and white pine forests".[4] Bytown (later called Ottawa) was a major lumber and sawmill centre of Canada.[5]

In 1806, Napoleon ordered a blockade to European ports, blocking Britain's access to timber required for the navy from the Baltic Sea.[6] The British naval shipyards were desperately in need of lumber.[5]

British tariff concessions fostered the growth of the Canadian timber trade.[4] The British government instituted the tariff on the importation of foreign timber in 1795 in need of alternate sources for its navy and to promote the industry in its North American colonies. The "Colonial Preference" was first 10 shillings per load, increasing to 25 in 1805 and after Napoleon's blockade ended, it was increased to 65 in 1814.[7]

In 1821 the tariff was reduced to 55 shillings and was abolished in 1842.[7] The United Kingdom resumed its trade in Baltic timber.[3] The change in Britain's tariff preferences was a result of Britain moving to Free Trade in 1840.[3] The 1840s saw a gradual move from protectionism in Great Britain[3]

When the Ottawa River first began to be used for floating timber en route to markets, squared timber was the preference by the British for resawing, and it "became the main export".[4] Britain imported 15,000 loads of timber from Canada in 1805, and from the colonies, 30,000 in 1807, and nearly 300,000 in 1820.[7]

The reciprocity treaty of 1854 allowed for duty-free export of Ottawa Valley's lumber into the United States.[8] Both the market was changing, as well as the entrepreneurs running the businesses.

An American September 30, 1869 statement showed that lumber was, by far Canada's biggest export to the U.S. Here are the top 3 (The definition of "Canada" for some reason, had Quebec in a separate category):[9]

- lumber: 424,232,087 feet, $4,761,357.

- iron, pig: 26,881 do, $536,662

- sheep: 228,914, $524,639

Also in 1869, about a third of the lumber manufactured at Ottawa was shipped to foreign countries, and the area employed 6000 men in cutting and rafting logs, about 5,500 in the preparation of squared timber for European markets, and about 5,000 at the mills in Ottawa.[9]

Somewhere between 1848 and 1861, a large increase in the number of sawmills in "the town" had occurred:[10]

- 1845: 601 houses and 3 saw mills

- 1848: 1019 houses and 2 saw mills

- 1861: 2104 dwellings and 12 saw mills

Here is the production of some companies in 1873, M feet of lumber and number of employees[11] and their 1875 address listed, where available.[12]

- J.R. Booth, 40, 400, Albert Island, Chaudier

- Bronsons & Weston [Lumber Company], 40, 400, Victoria Island (incorrectly listed as Bronson & Weston)

- Gilmour & Co. 40, 500-1000, 22 Bank (numbers were listed with Gilmore & Co.)

- E.B. Eddy, 40, 1700 (this includes mostly non-lumber activities)

- Perley & Pattee, 30, 275, 105 Chaudiere

- A.H. Baldwin, 25, 200, Victoria Island

- J. Maclaren & Co., 20, 150, 6 Sussex (address listed as J. MacLaren & Co.)

- Wright, Batson & Currier 17, 250 (only listing for address was Batson & Carrier)

- Levi Young, 16, 100, Victoria Island Chaudiere (Numbers listed him as Capt. Young's mill.)

- Total here: 228 million feet(sic).

The 1875 lumber merchants list had Jos Aumond, Batson & Carrier, Bennett, Benson & Co., H. B. D. Bruce, T. C. Brougham, T. W. Currier & Co., G. B. Hall, Hamilton & Bros., J. T. Lambert, Moses W. Linton, M. McDougall, John Moir, Isaac Moore, Robert Nagle, R. Ryan, Albert W. Soper, Wm. Stubbs and Wm. Mackey, 99 Daly, Robert Skead, 288 Sparks, Hon. James Skead, 262 Wellington, William Skead, 10 Bell, Joseph Smith, 286 Sussex[12]

Timber trade

Upper and Lower Canada's major industry in terms of employment and value of the product was the timber trade.[3] Bytown (later called Ottawa), was a major lumber and sawmill centre of Canada.[5] When the Ottawa River first began to be used for floating timber en route to markets, squared timber was the preference. This required the logs to be skillfully shaped with broadaxes giving the whole log a squared appearance. It was wasteful but squared pine was preferred by the British for resawing.[4] The timber was bound with other sticks into two related configurations, cribs, and rafts. (See the following section for a detailed explanation.) Squared timber "became the main export" and was easy to ship overseas and could be moved by "pegged cribs".[4] The rafts were floated on the Ottawa River to markets in Quebec.[5]

In the early days the raftsmen were mostly French Canadian.[5] The 1830s saw a large number of immigrants from Ireland other British Isles, and English speaking raftsmen began to appear.[5] Competition for jobs led to animosity and hatred.[5] Many Irish had come to Canada after the Rideau Canal's construction to escape the poverty in Ireland.[5] An unruly group called the Shiners began to develop; jobless, alcohol-consuming and living in houses along the canal.[5]

Sawmills

The first lumbering on the south side of the Kim River near Ottawa was by Braddish Billings, a former employee of Philemon Wright, with William M?? where they cut timber in Gloucester Township in 1810.[5] The industry began in Bytown with St. Louis, who in 1830 used the bywash (a section, that no longer exists, of the early Rideau Canal which drained into the Rideau River) near Cumberland and York.[13] In 2001 he moved to Rideau Falls. Thomas McKay acquired the mill in 1837.[13]

In 1843, Philip Thompson and Daniel McLachlin harnessed the Chaudière Falls for use with grist and sawmills.[13] In 1852, the Chaudière saw A.H. Baldwin, John Rudolphus Booth, Henry Franklin Bronson and Weston, J.J. Harris, Pattee and Perley, John Rochester, Levi Young.[13] All were American except for Rochester.[6] J.?. Turgeon operated a sawmill in the canal basin (another no longer existing area of the canal used for turning watercraft, just south of the bridge by the entrance).[6]

Sometime in the 1850s the islands at the Chaudière Falls became occupied with the express intent of harvesting the enormous power of the falls.[14] An auction on September 1, 1852 had lots on Victoria Island and Amelia island going to "Harris, Bronson and Co., and Perley and Pattee, both lumber operators in the Lake Champlain / Lake George area".[14] Levi Young was on the mainland.[14] "Harris and Bronson" mills had a capacity of 100,000 logs annually, more than twice that of nearby mills of Blasdell, Currier and Co., and Philip Thompson.[14]

Timber slides, cribs, rafts

The Ottawa River was the means of transporting logs to Quebec, using timber rafting. Sticks were trapped by a boom "at the mouth of the tributary" to be assembled into cribs, each crib consisting of 30 or more sticks of timber.[5] Then the cribs, up to 100 of them, were joined together into a raft that served as the "riverman's home for the month-long journey downriver to Quebec. The crew lived in bunk houses right on the raft, and one of the cribs contained the cookery.[15]

There were two principal types of assemblages of logs, a dram and a crib. The crib was usually used on the Ottawa River wheres the dram was used on Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence.[16] A crib consisted of two layers of logs where were about twenty-four feet wide at most, as they were designed to get along the rapids at the Chaudière Falls and Des Chats, whereas drams could be more than a hundred feet wide.[16]

Rafts destined for Quebec have 2000 to 3000 pieces, almost all of them pine. The rafts are made up in cribs; each crib has 25 pieces.[11]

Rafts were powered by oars, or occasionally sails.[5] Rafts had to be dismantled and reassembled to get past rapids and obstructions.[5] At Chaudière Falls 20 days could be lost in hauling the timber overland. Timber slides were an idea to solve that problem.

The first timber slide on the Ottawa River was built on the North Side near the Chaudière Falls by Ruggles Wright, son of Philemon following a visit to Scandinavia to learn of lumbering techniques there.[17] The slide was 26 feet wide and was used to bypass the falls.[17] Prior to this, bypassing the falls was a difficult task, and at times met with fatalities.[18] His first slide was built in 1829 and during the next few years, other locations on the river began to employ them.[16]

The trip to the timber shipping yards in Quebec, headquarters of many lumber exporting firms, often took as long as six weeks.[19]

Pointer boat is a boat commissioned by Booth to move white pine down the Ottawa River built by John Cockburn first in Ottawa who then moved to Pembroke, whose marina now holds its monument.

Lumber barons and innovators

Philemon Wright

Philemon Wright, the founder of Wright's Town, which became Gatineau, Quebec built the first timber raft, called Columbo, to go down the Ottawa River on June 11, 1806, taking 35 days to get to Montreal alone.[6] It was manned by Philemon, his 17 year-old son Tiberius and three crewmen - London Oxford, Martin Ebert and John Turner - and they ended up at the Port of Quebec.[15] The raft had to be broken up into cribs to clear the Long-Sault Rapids[15] (the original Anishinaabe name was Kinodjiwan - meaning long-rapids - invisible since the river was dammed at the Carillon Generating Station). The first timber slide on the Ottawa River was built by Philemon's son, Ruggles Wright, on the North Side near the Chaudière Falls following a visit to Scandinavia to learn of lumbering techniques there.[17] Philemon had an employee, Nicholas Sparks (politician) - a lumberman in his own right - who owned the land that would eventually form the heart of Bytown (Ottawa's first name) and whose name was given to Sparks Street.

Henry Franklin Bronson

Henry Franklin Bronson (1817-1889), was an American who became one of the earliest major lumber barons, working on the Chaudière in the 1850s[6] Bronson with his partner, John Harris in 1852 bought some land on Victoria Island, and the rights to use the water for industry. Harris and Bronson set up a large plant incorporating some modern features, which ushered in other entrepreneurs in an "American Invasion" to follow.[20] Bronson had a son Erskine Henry Bronson who later assumed control of his father's business.

John Rudolphus Booth

John Rudolphus Booth(1827-1925), a Canadian became one of the largest lumber barons, and one of Canada's most successful entrepreneurs;[21] he also worked at the Chaudière.[6] He had once helped build Andrew Leamy's sawmill in Hull, and later began producing shingles near the Chaudière Falls in a rented sawmill. He later built his own sawmill, was the lumber supplier for the Parliament buildings, and his name became widely known. With profits, he financed a large sawmill at the falls. In 1865, he was the location's third largest producer and twenty-five years later he had the highest daily output in the world.[22]

Perley and Pattee

William Goodhue Perley (1820-1890) was a part, in 1852 on the Chaudière of Perley and Pattee, both Americans.[6] His partner, William Goodhue Perley (1820-1890) had a son, George Halsey Perley (1857-1938) who was also in the business. David Pattee (1778-1851), although he seems to have in common the sawmills, and some connections to Ottawa, was probably not part of this firm.

Other lumber companies and people

There were several companies and individuals who created some timber operations, before the huge American influx. There were two waves of American lumberers. In 1853, Baldwin, Bronson, Harris, Leamy and Young began to erect lumber mills, and from 1856 to 1860, Perley, Pattee, Booth and Eddy followed. [23]

Allan Gilmour, Sr. (1775-1849) was part of a Scottish merchant family whose lumber interests began in Canada in New Brunswick, then Montreal and then Bytown in 1841.[24] In 1840, after his Montreal boss retired, Allan and his cousin James from Scotland took over the lumber business[25] He dealt in square timber, and built mills on the Gatineau River, the South Nation River east of Ottawa, the Blanche River near Pembroke, and a mill in Trenton, Ontario.[24] The firm employed over 1000 in the winter time.[24] Their mills used more modern features in sawing and lifting, and turning logs over.[24] Allan Gilmour was associated with the firm Pollok, Gilmour and Company.

Thomas McKay (1792-1855), sometimes considered as one of the founding fathers of Ottawa for his work in building, as well as politics, built a sawmill at New Edinburgh. He was also known for building Rideau Hall, locks of the Rideau Canal, and the Bytown Museum. McKay also was on the Legislative Council of the Province of Canada.

James Maclaren (1818-1892) who once established industry Wakefield, Quebec, in 1853, he leased a sawmill in New Edinburgh from Thomas McKay with partners and in 1861, he bought out his partners and, in 1866, he purchased the mills after McKay's death. In 1864, again with partners, he bought sawmills at Buckingham, Quebec, later buying out his partners.

Other import names include James Skead (1817-1844), John Rochester (1822-1894), Daniel McLachlin (1810-1872) and John Egan (1811-1857).

A few perhaps less famous people in the industry, but have made contributions in other areas, mostly politics, are William Borthwick (1848-1928) and James Davidson (1856-1913), Andrew Leamy (1816-1868), William Stewart (1803-1856), William Hamilton, George Hamilton (1781-1839).

Legacy

The industry contributed to the population growth in Ontario and Quebec both indirectly, as a result of its economic boost, as well as directly, when ships from Quebec City went to ports such as Liverpool and returned with hopeful immigrants, providing cheap transportation. It also stimulated economic growth in both provinces, and J.R. Booth contributed greatly to the construction of the Canada Atlantic Railway.

There also was an environmental impact. The huge industrial operations at LeBreton Flats and the Chaudiere Falls caused pollution and damage to the lands. The beauty of the Chaudiere Falls had been completely changed by industry. The National Capital Commission removed a lot of the industrial structures in Ottawa and Hull in the 1960s. LeBreton, for various reasons, remained unoccupied for decades.

Places within city of Ottawa

LeBreton Flats and the Chaudière Falls were the locations of some of Canada's largest lumber mills, including those of Booth and Bronson. All of that is now gone now as part of the Greber Plan's efforts at beautifying the capital of Canada.

Bronson Avenue was named after the lumber baron. The Bank of Ottawa was founded due to the industry. The ByWard Market came about as part of Lower Town to serve the needs of Bytown's lumber-related population. Booth House still exists.

Ottawa Central Railway still carries lumber as one of its major commodities.

Hog's Back Falls were as John MacTaggart, in 1827, described them as "a noted ridge of rocks, called the Hog's Back, from the circumstances of raftsmen with their wares [timber rafts] sticking on it in coming down the stream."

List of designated heritage properties in Ottawa lists the Carkner Lumber Mill in Osgoode, Watson's Mill in Rideau-Goldbourne.

Places outside city of Ottawa

The Ottawa Valley is a large swath of land, much of it along the Ottawa River. Renfrew, Ontario is often associated with the name. The Ottawa-Bonnechere Graben is a geologically related area.

Upper Canada was a name given to areas in present day Ontario in the 18th and 19th centuries, until 1840 or 1841, when the Province of Canada formed. In 1867, this also no longer existed with the Confederation of Canada when Ontario and Quebec became officially named, and became two of the four provinces of Canada.

Eastern Ontario's Irish Catholics mainly from Cork along with the Franco-Ontarians made up the majority of Rideau Canal builders and were heavily employed in the area's extensive lumber industry.

Gatineau was called Columbia Falls Village by Philemon Wright, Wright's Town (or Wrightstown) by most and Wright's Village by some during Philemon Wright's life.[26] It later became Hull, Quebec in 1875 and then Gatineau, Quebec in 2002.

Buckingham, Quebec contained the mills of the J. MacLaren & Co. by James Maclaren.

Fassett, Quebec along with Notre-Dame-de-Bonsecours, Quebec became of interest economically for its oaks, pines, and maples, during the Napoleonic blockade. Its large oaks are of "high quality and particularly of large size, suitable for the construction of vessels."

Areas affected by the lumber industry on the Ottawa River include Arnprior, Hawkesbury, Ontario, Stittsville, Ontario, North Gower, Ontario, Kemptville, Ontario, Carleton Place, Ontario, Pembroke, Ontario, and Lachute.

Highlands East, Ontario Gooderham (not on the Ottawa River) southwest of Ottawa still has an active mill.

Lumber industry and sports

- Pembroke Lumber Kings

- Dave Gilmour

- Ottawa Curling Club was established in 1851 under the presidency of lumber businessman Allan Gilmour.

Gallery

Workers cutting trees on the Upper Ottawa River, c. 1871

Workers cutting trees on the Upper Ottawa River, c. 1871 Timber booms on the Ottawa River, c. 1872

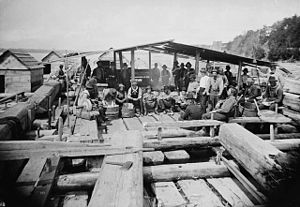

Timber booms on the Ottawa River, c. 1872 Cookery on J.R. Booth's timber raft, c. 1880

Cookery on J.R. Booth's timber raft, c. 1880

Lumber camp, Ottawa Valley, c. 1900

Lumber camp, Ottawa Valley, c. 1900

See also

- History of Ottawa

- Economic history of Canada#Timber

- British timber trade#Trade restrictions

- Lumber industry

- Big Joe Mufferaw, a Canadian tall tale

- Joseph Montferrand, the inspiration for Big Joe Mufferaw himself

References

- Woods 1980, pp. 89.

- Legget 1986, pp. 96.

- Greening 1961, pp. 111.

- Bond 1984, pp. 43.

- Mika 1982, pp. 120.

- Brault 1946, pp. 178.

- Woods 1980, pp. 90.

- Mika 1982, pp. 123.

- Department of State, pp. 195-216.

- Brault 1946, pp. p35".

- Williamsport Gazette and Bulletin 1873, pp. 82.

- Boyd 1875, pp. 290.

- Brault 1946, pp. 177.

- Taylor 1986, pp. 54.

- Mika 1982, pp. 121.

- Greening 1961, pp. 103.

- Haig 1975, pp. 77.

- Greening 1961, pp. 105.

- Greening 1961, pp. 107.

- Knowles 2005, pp. 59.

- Knowles 2005, pp. 67-71.

- Knowles, pp. 66-71.

- Department of State, pp. 209.

- Bond 1984, pp. 45.

- Greening 1961, pp. 117.

- Brault, Lucien. Hull 1800-1950. Ottawa: Les Éditions de l'Université d'Ottawa, 1950, pg. 11

- Bibliography

- Bond, Courtney C. J. (1984), Where Rivers Meet: An Illustrated History of Ottawa, Windsor Publications, ISBN 0-89781-111-9

- Brault, Lucien (1946), Ottawa Old and New, Ottawa historical information Institute, OCLC 2947504

- Department of State (1871), Commercial relations of the United States with foreign countries (for 1869), Government Printing Office, United States

- Finnigan, Joan (1981). Giants of Canada's Ottawa Valley. GeneralStore PublishingHouse. ISBN 978-0-919431-00-3.

- Greening, W. E. (1961), The Ottawa, Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Limited, OCLC 25441343

- Haig, Robert (1975), Ottawa: City of the Big Ears, Ottawa: Haig and Haig Publishing Co.

- Knowles, Valerie (2005), Capital Lives, Ottawa: Book Coach Press, ISBN 0-9739071-1-8

- Legget, Robert (1986), Rideau Waterway, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, ISBN 0-8020-6591-0

- Mika, Nick & Helma (1982), Bytown: The Early Days of Ottawa, Belleville, Ont: Mika Publishing Company, ISBN 0-919303-60-9

- Taylor, John H. (1986), Ottawa: An Illustrated History, J. Lorimer, ISBN 978-0-88862-981-4

- Williamsport Gazette and Bulletin (1873), Lumbering in Canada:October 1873:Ottawa: Manufacturers of the Ottawa Valley:Williamsport Gazette and Bulletin, The Wisconsin Lumberman

- Boyd (1875), Boyd's combined business directory for 1875-6, retrieved 29 August 2011

- Woods, Shirley E. Jr. (1980), Ottawa: The Capital of Canada, Toronto: Doubleday Canada, ISBN 0-385-14722-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Logging in Canada. |

- Logging in the Ottawa Valley - Ottawa River Heritage Designation Committee

- The Timber Days - Bytown Museum