Orange Line (MBTA)

The Orange Line is one of the four subway lines of the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. It extends from Forest Hills in Jamaica Plain, Boston in the south to Oak Grove in Malden in the north. It meets the Red Line at Downtown Crossing, the Blue Line at State, and the Green Line at Haymarket and North Station. It connects with Amtrak service at Back Bay and North Station, and with MBTA Commuter Rail service at Back Bay, North Station, Forest Hills, Ruggles station in Roxbury, and Malden Center in Malden. From 1901 to 1987, it provided the first elevated rapid transit in Boston; the last elevated section was torn down in 1987 when the southern portion of the line was moved to the Southwest Corridor.

| Orange Line | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

An inbound train passing the Wellington Yard signal tower | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Rapid transit | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| System | MBTA subway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Operational | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Boston, Massachusetts | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Termini | Oak Grove Forest Hills | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stations | 20 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Daily ridership | 201,000 (2019)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | 1901 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | MBTA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator(s) | MBTA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rolling stock | Hawker Siddeley #12 Main Line cars CRRC #14 Orange Line cars | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line length | 11 miles (18 km) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrification | Third rail | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All stations on the Orange Line are handicapped accessible. These stations are equipped with high-level platforms for easy boarding, as well as elevators for easy platform access.

History

Construction

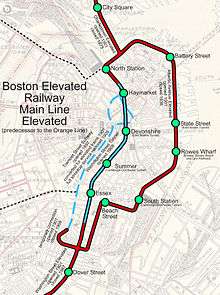

The Main Line of the electric Boston Elevated Railway opened in segments, starting in 1901. It proceeded from Sullivan Square along the Charlestown Elevated to the Canal Street incline near North Station. It was carried underground by the Tremont Street subway (now part of the Green Line), returning above ground at the Pleasant Street incline (now closed, located just south of Boylston station). A temporary link connected from there to the Washington Street Elevated, which in 1901 ran from this point via Washington Street to Dudley Square (which is most of what is now Phase 1 of the Silver Line).

Also in 1901, the Atlantic Avenue Elevated opened, branching at Causeway Street to provide an alternate route through downtown Boston (along the shoreline, where today there is no rail transit) to the Washington Street Elevated.

In 1908, a new Washington Street Tunnel opened, allowing Main Line service to travel from the Charlestown Elevated, underground via an additional new portal at the Canal Street incline, under downtown Boston and back up again to meet the Washington Street Elevated and Atlantic Avenue Elevated near Chinatown. The stations wee richly decorated with tile work, mosaics, and copper; after criticism of the large Tremont Street subway headhouses, most entrances were comparatively modest and set into buildings.[2] Use of the parallel Tremont Street subway was returned exclusively to streetcars.

By 1909, the Washington Street Elevated had been extended south to Forest Hills. Trains from Washington Street were routed through the new subway, either all the way to Sullivan Square, or back around in a loop via the subway and then the Atlantic Avenue Elevated.

In 1919, the same year that the Atlantic Avenue Elevated was partially damaged in Boston's Great Molasses Flood, the Charlestown Elevated was extended north from Sullivan Square to Everett, over surface right-of-way parallel to Alford Street/Broadway, with a drawbridge over the Mystic River.[3] The Boston Elevated had long-term plans to continue this extension further north to Malden, a goal which would only be achieved decades later, under public ownership and not via the Everett route.

Closure of Atlantic Avenue Elevated and ownership changes

.jpg)

Following a 1928 accident at a tight curve on Beach Street, the southern portion of the Atlantic Avenue Elevated, between South Station and Tower D on Washington Street, was closed (except for rush-hour trips from Dudley to North Station via the Elevated), breaking the loop; non-rush-hour Atlantic Avenue service was reduced to a shuttle between North and South Stations.[3] In 1938, the remainder of the Atlantic Avenue Elevated was closed, leaving the subway as the only route through downtown – what is now the Orange Line between Haymarket and Chinatown stations.

Ownership of the railway was transferred from the private Boston Elevated Railway to the public Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) in 1947; the MTA was itself reconstituted as the modern Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) in 1964.

Orange Line naming

The line was known as the Main Line Elevated under the Boston Elevated Railway, and the Forest Hills–Everett Elevated (Route 2 on maps) under the Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

After taking over operations in August 1964, the MBTA began rebranding many elements of Boston's public transportation network. Colors were assigned to the rail lines on August 26, 1965 as part of a wider modernization developed by Cambridge Seven Associates. Peter Chermayeff assigned red, green, and blue to the other three lines based on geographic features; however, according to Chermayeff, the Main Line El "ended up being orange for no particular reason beyond color balance."[4] The firm originally planned for yellow instead of orange, but yellow was rejected after testing because yellow text was difficult to read on a white background.[5] (Yellow was later used for MBTA bus service). The MBTA and transit historians later claimed that orange came from Orange Street, an early name for what is now part of Washington Street.[6][7][5]

In January and February 1967, the four original Washington Street Tunnel stations were renamed. Transfer stations were given the same name for all lines: Winter and Summer stations plus Washington on the Red Line became Washington, Milk and State plus Devonshire on the Blue Line became State Street after the cross street, and Union and Friend plus Haymarket Square on the Green Line became Haymarket after Haymarket Square.[3] Boylston Street was renamed Essex to avoid confusion with nearby Boylston station on the Green Line.[3]

In May 1987, Essex was renamed Chinatown after the adjacent Chinatown neighborhood, and Washington renamed Downtown Crossing after the adjacent shopping district.[3] In March 2010, New England Medical Center station was renamed as Tufts Medical Center two years after the eponymous hospital changed its name.[3]

Rerouting of Charlestown and Everett service

The Boston Transportation Planning Review looked at the line in the 1970s, considering extensions to reach the Route 128 beltway, with termini at Reading in the north and Dedham in the south. As a result of this review, the Charlestown Elevated – which served the Charlestown neighborhood north of downtown Boston and the inner suburb of Everett – was demolished and replaced in 1975.

The Haymarket North Extension rerouted the Orange Line through an underwater crossing of the Charles River. Service in Charlestown was replaced with service along Boston and Maine tracks routed partially beneath an elevated section of Interstate 93, ultimately to Wellington and then to Oak Grove in Malden, Massachusetts instead of Everett. Rail service to Everett was replaced with buses.

The extension was unique among Boston transit lines as it contained a third express track between Wellington and Community College stations. These stations, along with Sullivan Sq, have two island platform stations as opposed to the more normal single island stations found on the southern side of the Orange Line. This express track was designed for the never-built extension north of Oak Grove to Reading. The third track would have allowed peak-direction express service as well as places to terminate trains. Service north of Oak Grove was planned to have longer headways to account for the lower projected ridership. This extension was opposed by residents of Melrose who preferred restored commuter rail service. Because of this the express track ends at Wellington and a single commuter rail track continues along the Orange Line north to Reading.

Closure of Washington Street Elevated

Construction of Interstate 95 into downtown Boston was cancelled in 1972 after local protest over the necessary demolition. However, land for I-95's Southwest Corridor through Roxbury had already been cleared of buildings; moreover, the state had already committed to using this vacant land for transportation purposes.[8] As a result, instead of an 8-lane Interstate highway with a relocated Orange Line running in its median (in a manner similar to the Chicago Transit Authority's Dan Ryan, Congress, and O'Hare branches), the space would be occupied by the realigned Orange Line, a reconstructed three-track mainline for Amtrak's Northeast Corridor and MBTA Commuter Rail trains, and a linear park. After this re-routing was accomplished in 1987, the Washington Street Elevated was torn down, the last major segment of the original elevated line to be demolished.

Between April 30 and May 3, 1987, the Washington Street Elevated south of the Chinatown station was closed to allow the Orange Line to be tied into the new Southwest Corridor. On May 4, 1987, the Orange Line was rerouted from the southern end of the Washington Street Tunnel onto the new Southwest Corridor. Instead of rising up to elevated tracks, it now veered west at the Massachusetts Turnpike and followed the Pike and the old Boston and Albany Railroad right-of-way to the existing MBTA Commuter Rail stop at Back Bay. It then continued along new tracks, partially covered and partially open but depressed, to Forest Hills. This MBTA right-of-way is also shared by Amtrak as part of the national Northeast Corridor intercity passenger rail service.

| External video | |

|---|---|

While ending more or less at the same terminus (Forest Hills), the new routing passes significantly to the west of its previous route on Washington Street; local residents were promised replacement service. Originally, plans provided for light rail vehicles street running in mixed traffic, from Washington Street to Dudley Square, then diverting southeastward on Warren Street towards Dorchester. In 2002, Phase 1 of the Silver Line bus rapid transit was added to connect Washington Street to the downtown subways, attempting to address this service need. This replacement service was controversial, as many residents preferred the return of rail transportation.[10]

Station renovations

In the mid-1980s, the MBTA spent $80 million to extend the platforms of seven Red Line and three Orange Line stations (Essex, Washington, and State) to allow the use of six-car trains.[11] Washington and Essex were made fully accessible, as was the northbound platform at Essex. The Southwest Corridor station opened in 1987 were all fully accessible. Six-car trains entered service on August 18, 1987.[3] Oak Grove was also renovated around 1987.[12]

This left only Haymarket, five stations on the Haymarket North Extension, and the southbound platform at Chinatown inaccessible by the 1990 passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act.[13] Construction at Sullivan Square and Wellington began in 1991.[6] Haymarket was retrofitted with elevators in 2000.[12] The 1975-built North Station was expanded into a "superstation" with a cross-platform transfer to the Green Line; elevators were in installed in 2001, though the Green Line did not use the station until 2004.[12][3] The southbound platform at Chinatown was made accessible in 2002.[14][12] Renovations to Community College and Malden Center were completed in 2005, making the Orange Line the first of the four original MBTA subway lines to become fully accessible.[14]

Assembly

In the early 2000s, Somerville began planning an infill station between Sullivan and Wellington to serve the new Assembly Square development. The $57 million station was funded by the state's Executive Office of Housing and Economic Development, FTA Section 5309 New Starts program, and Federal Realty Investment Trust (the developer of Assembly Square).[15] Construction began in late 2011 and finished in mid 2014.[16] The new station, Assembly, opened on September 2, 2014.[17] It was the first new station on the MBTA subway system since 1987.[17]

Winter issues and resiliency work

During the unusually brutal winter of 2014–2015, the entire MBTA system was shut down on several occasions by heavy snowfalls. The aboveground sections of the Orange and Red lines were particularly vulnerable due to their exposed third rail, which iced over during storms. When a single train stopped due to power loss, other trains soon stopped as well; without continually running trains pushing snow off the rails, the lines were quickly covered in snow. (Because the Blue Line was built with overhead lines on its surface section due to its proximity to corrosive salt air, it was not subject to icing issues.)

Starting in 2015, the MBTA began implementing its $83.7 million Winter Resiliency Program, much of which focused on preventing similar issues with the Orange and Red lines. The Southwest Corridor section of the Orange Line is located in a trench and is protected from the worst weather, but the 1970s-built Haymarket North Extension had older infrastructure and was in worse shape. From Sullivan Square north, it is exposed to the weather and largely built on an embankment, rendering it more vulnerable. That section is receiving new heated third rail, switch heaters, and snow fences to reduce the impacts of inclement weather.[18][19] The work requires bustitution of the line from Sullivan Square to Oak Grove on certain weeknights and weekends.[20][21]

In October 2018, the MBTA awarded a $218 million signal contract for the Red and Orange Lines, which will allow 4.5-minute headways on the Orange Line beginning in 2022.[22]

Historical routes

Station listing

| Location | Station | Opened | Notes and connections |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malden | March 20, 1977 | ||

| December 27, 1975 | |||

| Medford | September 6, 1975 | ||

| Somerville | September 2, 2014 | ||

| Charlestown, Boston | April 7, 1975 | Original elevated station was open from June 10, 1901 to April 4, 1975 | |

| North End, Boston | Original elevated station was open from June 10, 1901 to April 4, 1975 | ||

| November 30, 1908 | |||

| Downtown Boston | |||

At Park Street: | |||

| Chinatown, Boston | |||

| May 4, 1987 | |||

| Back Bay, Boston | |||

| South End, Boston | |||

| Roxbury, Boston | |||

| Jamaica Plain, Boston | |||

| Original elevated station was open from November 22, 1909 to April 30, 1987 |

Rolling stock

| Series # | Year built | Manufacturer | Car length |

Car width |

Photo | Fleet numbers (total ordered) |

Amount active (as of June 2020) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #12 Main Line |

1979–1981 | Hawker Siddeley Canada | 65 ft (20 m) | 9 ft 3 in (2.82 m) |  |

|

114 |

| #14 Orange |

2018–2022 | CRRC | 65 ft (20 m) | 9 ft 3 in (2.82 m) |  |

|

18[23] |

_Interior.jpg)

The "T" previously had a fleet of Pullman-Standard heavy rail cars for the Orange Line. These cars, known as 01100s, had been in service since the 1950s, and saw service on both the elevated and the northern extension before they were retired in 1981. Several remained on the property for some time before being scrapped. The 01100 cars were a favorite for fans, as the small motorman's cab enabled passengers to stand at the front for an operator's-eye view.

The Orange Line is standard-gauge heavy rail and uses a third rail for power. The current fleet was built between 1979 and 1981 by Hawker Siddeley Canada (now Alstom) of Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada. They are 65 feet (20 m) long and 9 ft 3 in (2.8 m) wide, with three pairs of doors on each side. They are based on the PA3 model used by PATH in New Jersey. There are 120 cars, numbered 01200-01319. All in-service Orange Line trains run in six-car consists.

New CRRC trains

In late 2008, the MBTA began the planning process for new Orange and Red Line vehicles. The agency originally planned for a simultaneous order for 146 Orange Line cars (to replace the whole fleet) and 74 Red Line cars (to replace the older 1500 and 1600 series cars). A similar order was used in the late 1970s for the current Orange Line cars and the old Blue Line cars, ordered at the same time and largely identical except for size and color.[24] In October 2013, MassDOT announced plans for a $1.3 billion subway car order for the Orange and Red Lines, which would provide 152 new Orange Line cars to replace the existing 120-car fleet and add more frequent service.[25]

On October 22, 2014, the MassDOT Board awarded a $566.6 million contract to a China based manufacturer CNR (which became part of CRRC the following year) to build 152 replacement railcars for the Orange Line, as well as additional cars for the Red Line.[26] The other bidders were Bombardier Transportation, Kawasaki Heavy Industries and Hyundai Rotem. CNR began building the cars at a new manufacturing plant in Springfield, Massachusetts, with initial deliveries expected in 2018 and all cars in service by 2023.[26] The Board forwent federal funding to allow the contract to specify the cars be built in Massachusetts, to create a local railcar manufacturing industry.[27] In conjunction with the new rolling stock, the remainder of the $1.3 billion allocated for the project would pay for testing, signal improvements and expanded maintenance facilities, as well as other related expenses.[26] Sixty percent of the car's components are sourced from the United States.[28]

After delays due to issues with the train's control system, the first new train entered revenue service on August 14, 2019;[29][30] Replacement of the signal system is expected to be complete by 2022 on the Orange Line; the total cost is $218 million for both the Red and Orange Lines.[31]

While waiting for new cars, service has deteriorated due to maintenance problems with the old cars. The number of trains at rush hour was reduced from 17 (102 cars) to 16 (96 cars) in 2011; in the same year, daily ridership surpassed 200,000.[32] Increased running times – largely due to longer dwell times from increased ridership – resulted in headways being lengthened from 5 minutes before 2011 to 6 minutes in 2016. The increased fleet size with the new trains will allow headways to be reduced to between 4 and 5 minutes at peak.[33] In the interim, a 2016 test of platform markings at North Station which show boarding passengers where to stand to avoid blocking alighting passengers resulted in a one-third decrease in dwell times.[34]

The new cars have faced several issues since their August entry into service. In November 2019, a car derailed while undergoing initial testing at the Wellington yard. The last car of a six car trainset had jumped the rails while going over a switch, however no major damage had been reported. Several months earlier, the first two trainsets were taken out of service due to safety issues following the inadvertent opening of a passenger door while the train was in motion.[35] Cars were also rechecked in early December 2019, after issues with sounds combined with passenger overload necessitated removal from service.[36][37] The first train was restored to service in January 2020.[38]

Facilities

The Orange Line has two tracks for most of its length; a third track is present between Wellington station and the Charles River portal.[39] This track is used to bypass construction on the other two, and for testing newly delivered cars for the Orange Line. The primary maintenance and storage facility is at Wellington station.[39] Had the Orange Line been extended to Reading, the third track would have been the northbound local track and the present-day northbound track would likely have become a bi-directional express track.

References

- "Quarterly Ridership Update: Third Quarter FY19" (PDF). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. May 20, 2019. p. 6.

- Coburn, Frederick W. (November 1910). "Rapid Transit and Civic Beauty". New Boston. Vol. 1 no. 7. pp. 307–314 – via Google Books.

- Belcher, Jonathan (27 June 2015). "Changes to Transit Service in the MBTA district" (PDF). NETransit. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Byrnes, Mark (September 17, 2018). "How Boston Got Its 'T'". CityLab.

I remember sitting in my Cambridge office preparing for a meeting with the MBTA in which I would be proposing colored lines. I had markers in front of me and I chose red for the line that went to Harvard since it’s a well-known institution whose main color is crimson. One line went up the North Shore of Boston up to the coastal areas, so it seemed obvious to call that the Blue Line. The line that serves Olmsted’s Emerald Necklace was an obvious choice for green. And then the fourth line ended up being orange for no particular reason beyond color balance.

- Ba Tran, Andrew (June 2012). "MBTA Orange Line's 111th anniversary". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on July 21, 2017.

The Everett-Forest Hills Main Line Elevated was renamed the Orange Line on Aug. 25, 1965. The name comes from a section of Washington Street between Essex and Dover streets that had the name Orange Street until the early 19th century, said Clarke. However, according to architecture firm Cambridge Seven Associates, the Orange Line's color was a design choice after the yellow color option did not test well.

- Sanborn, George M. (1992). A Chronicle of the Boston Transit System. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority – via MIT.

- "Curiosity Carcards" (PDF). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. 2012.

- Anderson, Steve. "Southwest Expressway (I-95, unbuilt)". bostonroads.com. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- "Orange Line El Stations". Boston TV Digital News. WGBH. April 30, 1987. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- "Roxbury-Dorchester-Mattapan Transit Needs Study" (PDF). Massachusetts Department of Transportation. September 2012. p. 53. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- 1985 Annual Report. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. 1985. p. 13 – via Internet Archive.

- Tran Systems and Planners Collaborative (August 24, 2007). "Evaluation of MBTA Paratransit and Accessible Fixed Route Transit Services: Final Report" (PDF). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority.

- Operations Directorate Planning Division (November 1990). "Ridership and Service Statistics" (3 ed.). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. pp. 1–4 – via Internet Archive.

- "Accessibility Projects at the MBTA" (PDF). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. March 2005.

- Moskowitz, Eric (6 October 2011). "MBTA board OK's millions for stations". Boston Globe. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- Coughlin, Kerri (25 October 2011). "Construction on Assembly Square T stop to begin later this fall". Tufts Daily. Archived from the original on 4 December 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- Hofherr, Justine (27 August 2014). "Somerville's New Assembly Square MBTA Station to Open Next Week". Boston Globe. Retrieved 27 August 2014.

- Vaccaro, Adam (23 September 2015). "Winter is coming, and the MBTA is getting ready". Boston Globe. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- "Gov. Baker Announces $83.7 Million MBTA Winter Resiliency Plan" (Press release). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. 4 June 2015.

- "Winter Resiliency Work Continues on the Red Line: WEEKEND TRAIN SERVICE BETWEEN JFK/UMASS AND QUINCY CENTER SUSPENDED" (Press release). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. 9 September 2015.

- Authority, Massachusetts Bay Transportation. "Weekend Orange Line Service Suspended between Sullivan and North Stations < News < MBTA Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority". www.mbta.com. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- Jessen, Klark (October 2, 2018). "MBTA Awards Signal Upgrade Contract for Red and Orange Lines" (Press release). Massachusetts Department of Transportation.

- "MBTA Vehicle Inventory Roster Page". . June 17, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020. External link in

|website=(help) - Central Transportation Planning Staff (December 2009). "CHAPTER 5: Priorities for Achieving a State of Good Repair" (PDF). The Program for Mass Transportation. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. p. 5-2.

- "Governor Patrick Announces Major Transportation Funding Investments" (Press release). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. 22 October 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- "Chinese Company Hopes MBTA Contract Will Be U.S. Launching Pad". WMUR.com. October 22, 2014. Archived from the original on October 23, 2014. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- MBTA: Orange Line problems not linked to Springfield-built cars

- Vantuono, William C. (October 1, 2019). "MBTA Orange Line Cars Pulled From Service: Report". Railway Age.

- "First New MBTA Orange Line Cars Enter Passenger Service" (Press release). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. August 14, 2019.

- Ruckstuhl, Laney (March 25, 2019). "MBTA Orange Line Car Rollout Delayed Until Summer". WBUR.

- Vaccaro, Adam (October 1, 2018). "Signal problem? MBTA takes aim at prime cause of delays with new signal system". Boston Globe.

- Dungca, Nicole (8 June 2016). "Your Orange Line commute is more crowded than it used to be". Boston Globe. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- "MBTA State of the Service: Orange Line Heavy Rail" (PDF). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. 6 June 2016. p. 26.

- Vaccaro, Adam (6 June 2016). "Why Orange Line trains are leaving North Station a little bit faster now". Boston Globe. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- Cotter, Sean Philip (November 18, 2019). "New Orange Line train becomes latest MBTA derailment". The Boston Herald. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- "MBTA finds cause of Orange Line's trains' 'uncommon noise'". WCVB. 2019-12-04. Retrieved 2019-12-05.

- "T pulls new Orange Line trains from service for 'uncommon noise'". Boston Herald. 2019-12-03. Retrieved 2019-12-05.

- Ellement, John R.; Vaccaro, Adam (January 7, 2020). "One new Orange Line train back on tracks as T says problems are fixed". The Boston Globe.

- "MBTA Orange Line". world.nycsubway.org. Retrieved 2012-06-17.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to MBTA Orange Line. |

- Official MBTA Orange Line information

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) documentation of Boston Elevated Railway Company's Main Line Elevated (Former Orange Line)

- Orange Line from nycsubway.org – Includes detailed description and photos of current Orange Line

- Jamaica Plain Historical Society – Orange Line Memories

- Jamaica Plain Historical Society – Orange Line Replaced Old Railroad Embankment

- "An Elevated View: The Orange Line", Boston Public Library exhibit about Orange Line elevated line history, October 2012 – January 2013 (BPL description)