Negro

In the English language, Negro (plural Negroes) is a term historically used to denote persons considered to be of Negroid heritage.[1] The term can be construed as offensive, inoffensive, or completely neutral, largely depending on the region or country where it is used. It has various equivalents in other languages of Europe.

In English

Around 1442, the Portuguese first arrived in Southern Africa while trying to find a sea route to India.[2][3] The term negro, literally meaning "black", was used by the Spanish and Portuguese as a simple description to refer to the Bantu peoples that they encountered. Negro denotes "black" in Spanish and Portuguese, derived from the Latin word niger, meaning black, which itself is probably from a Proto-Indo-European root *nekw-, "to be dark", akin to *nokw-, "night".[4][5] "Negro" was also used of the peoples of West Africa in old maps labelled Negroland, an area stretching along the Niger River.

From the 18th century to the late 1960s, negro (later capitalized) was considered to be the proper English-language term for people of black African origin. According to Oxford Dictionaries, use of the word "now seems out of date or even offensive in both British and US English".[1]

A specifically female form of the word, negress (sometimes capitalized), was occasionally used. However, like Jewess, it has all but completely fallen from use.

"Negroid" has traditionally been used within physical anthropology to denote one of the three purported races of humankind, alongside Caucasoid and Mongoloid. The suffix -oid means "similar to". "Negroid" as a noun was used to designate a wider or more generalized category than Negro; as an adjective, it qualified a noun as in, for example, "negroid features".[6]

United States

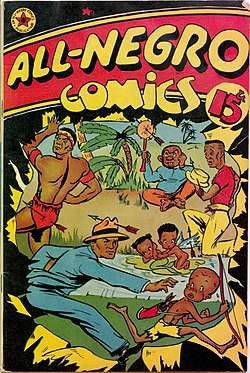

Negro superseded colored as the most polite word for African Americans at a time when black was considered more offensive.[7] In 17th-century Colonial America, the term "Negro" had been also, according to one historian, used to describe Native Americans.[8] John Belton O'Neall's The Negro Law of South Carolina (1848) stipulated that "the term negro is confined to slave Africans, (the ancient Berbers) and their descendants. It does not embrace the free inhabitants of Africa, such as the Egyptians, Moors, or the negro Asiatics, such as the Lascars."[9] The American Negro Academy was founded in 1897, to support liberal arts education. Marcus Garvey used the word in the names of black nationalist and pan-Africanist organizations such as the Universal Negro Improvement Association (founded 1914), the Negro World (1918), the Negro Factories Corporation (1919), and the Declaration of the Rights of the Negro Peoples of the World (1920). W. E. B. Du Bois and Dr. Carter G. Woodson used it in the titles of their non-fiction books, The Negro (1915) and The Mis-Education of the Negro (1933) respectively. "Negro" was accepted as normal, both as exonym and endonym, until the late 1960s, after the later Civil Rights Movement. One well-known example is the identification by Martin Luther King, Jr. of his own race as "Negro" in his famous "I Have a Dream" speech of 1963.

However, during the 1950s and 1960s, some black American leaders, notably Malcolm X, objected to the word Negro because they associated it with the long history of slavery, segregation, and discrimination that treated African Americans as second class citizens, or worse.[10] Malcolm X preferred Black to Negro, but also started using the term Afro-American after leaving the Nation of Islam.[11]

Since the late 1960s, various other terms have been more widespread in popular usage. These include black, Black African, Afro-American (in use from the late 1960s to 1990) and African American.[12] Like many other similar words, the word "black", of Anglo-Saxon/Germanic origin, has a greater impact than "Negro", of French/Latinate origin (see Linguistic purism in English). The word Negro fell out of favor by the early 1970s. However, many older African Americans initially found the term black more offensive than Negro.

The term Negro is still used in some historical contexts, such as the songs known as Negro spirituals, the Negro Leagues of sports in the early and mid-20th century, and organizations such as the United Negro College Fund.[13][14] The academic journal published by Howard University since 1932 still bears the title Journal of Negro Education, but others have changed: e.g. the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (founded 1915) became the Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History in 1973, and is now the Association for the Study of African American Life and History; its publication The Journal of Negro History became The Journal of African American History in 2001. Margo Jefferson titled her 2015 book Negroland: A Memoir to evoke growing up in the 1950s and 1960s in the African-American upper class.

The United States Census Bureau included Negro on the 2010 Census, alongside Black and African-American, because some older black Americans still self-identify with the term.[15][16][17] The U.S. Census now uses the grouping "Black, African-American, or Negro". Negro is used in efforts to include older African Americans who more closely associate with the term.[18] On the other hand, the term has been censored by some newspaper archives.[19]

Liberia

The constitution of Liberia limits Liberian nationality to Negro people (see also Liberian nationality law).[20] People of other racial origins, even if they have lived for many years in Liberia, are thus precluded from becoming citizens of the Republic.[21]

In other languages

Latin America (Portuguese and Spanish)

In Spanish, negro (feminine negra) is most commonly used for the color black, but it can also be used to describe people with dark-colored skin. In Spain, Mexico, and almost all of Latin America, negro (lower-cased, as ethnonyms are generally not capitalized in Romance languages) means just 'black colour' and it doesn't refer by itself to any ethnic or race unless further context is provided. As in English, this Spanish word is often used figuratively and negatively, to mean 'irregular' or 'undesirable', as in mercado negro ('black market'). However, in Spanish-speaking countries where there are fewer people of West African slave origin, such as Argentina and Uruguay, negro and negra are commonly used to refer to partners, close friends[22] or people in general, independent of skin color. In Venezuela the word negro is similarly used, despite its large West African slave-descended population percentage.

In certain parts of Latin America, the usage of negro to directly address black people can be colloquial. It is important to understand that this is not similar to the use of the word nigga in English in urban hip hop subculture in the United States, given that "negro" is not a racist term. For example, one might say to a friend, "Negro ¿Cómo andas? (literally 'Hey, black-one, how are you doing?'). In such a case, the diminutive negrito can also be used, as a term of endearment meaning 'pal'/'buddy'/'friend'. Negrito has thus also come to be used to refer to a person of any ethnicity or color, and also can have a sentimental or romantic connotation similar to 'sweetheart' or 'dear' in English. In other Spanish-speaking South American countries, the word negro can also be employed in a roughly equivalent term-of-endearment form, though it is not usually considered to be as widespread as in Argentina or Uruguay (except perhaps in a limited regional or social context). It is consequently occasionally encountered, due to the influence of nigga, in Chicano English in the United States.

In Portuguese, negro is an adjective for the color black, although preto is the most common antonym of branco ('white'). In Brazil and Portugal, negro is equivalent to preto, but it is far less commonly used. In Portuguese-speaking Brazil, usage of "negro" heavily depends on the region. In the state of Rio de Janeiro, for example, where the main racial slur against black people is crioulo (literally 'creole', i.e. Americas-born person of West African slave descent), preto/preta and pretinho/pretinha can in very informal situations be used with the same sense of endearment as negro/negra and negrito/negrita in Spanish-speaking South America, but its usage changes in the nearby state of São Paulo, where crioulo is considered an archaism and preto is the most-used equivalent of "negro"; thus any use of preto/a carries the risk of being deemed offensive.

In Venezuela, particularly in cities like Maracaibo negro has a positive connotation and it is independent if the person saying it or receiving it is of black color or not. It is typically used to replace phrases like amor (Love), mamá (Mother), amigo (Friend) and other similar ones. A couple could say negra (female form) or negro (male form) to the other person and ask for attention or help with no negative meaning whatsoever.

Spanish East Indies

.jpg)

In the Philippines, which historically had almost no contact with the Atlantic slave trade, the Spanish-derived term negro (feminine negra; also spelled nigro or nigra) is still commonly used to refer to black people, as well as to people with dark-colored skin (both native and foreign). Like in Spanish usage, it has no negative connotations when referring to black people. However, it can be mildly pejorative when referring to the skin color of other native Filipinos due to traditional beauty standards. The use of the term for the color black is restricted to Spanish phrases or nouns.[23][24]

Negrito (feminine negrita) is also a term used in the Philippines to refer to the various darker-skinned native ethnic groups that partially descended from early Australo-Melanesian migrations. These groups include the Aeta, Ati, Mamanwa, and the Batak, among others. Despite physical appearances, they all speak Austronesian languages and are genetically related to other Austronesian Filipinos. The island of Negros is named after them.[25] The term Negrito has entered scientific usage in the English language based on the original Spanish/Filipino usage to refer to similar populations in South and Southeast Asia.[26] However, the appropriateness of using the word to bundle people of similar physical appearances has been questioned as genetic evidence show they do not have close shared ancestry.[27][28]

Other Romance languages

Italian

In Italian, negro (male) and negra (female) were used as neutral term equivalents of "negro". In fact, Italian has three variants : "negro", "nero" and "di colore". The first one is the most historically attested and was the most commonly used until the 1960s as an equivalent of the English word negro. It was gradually felt as offensive during the 1970s and replaced with "nero" and "di colore". "Nero" was considered a better translation of the English word "black", while "di colore" is a loan translation of the English word "colored".[29]

Today, the word is currently considered offensive[30][31][32] but some attestations of the old use can still be found.

For example, famed 1960s pop singer Fausto Leali is still called il negro bianco ("the white negro") in Italian media,[33][34][35] on account of his naturally hoarse style of singing.

In Italian law, Act No. 654 of 13 October 1975 (known as the “Reale Act"), as amended by Act No. 205 of 25 June 1993 (known as the “Mancino Act") and Act No. 85 of 24 February 2006, criminalizes incitement to and racial discrimination itself, incitement to and racial violence itself, the promotion of ideas based on racial superiority or ethnic or racist hatred and the setting up or running of, participation in or support to any organisation, association, movement or group whose purpose is the instigation of racial discrimination or violence.[36][37]

As the Council of Europe noted in its 2016 report, "the wording of the Reale Act does not include language as ground of discrimination, nor is [skin] color included as a ground of discrimination."[37] However, the Supreme Court, in affirming a lower-court decision, declared that the use of the term negro by itself, if it has a clearly offensive intention, may be punishable by law,[38] and is considered an aggravating factor in a criminal prosecution.[39]

French

_%D9%86%D9%87%D8%AC_%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%88%D8%B5%D9%81%D8%A7%D9%86.jpg)

In the French language, the existential concept of negritude ('blackness') was developed by the Senegalese politician Léopold Sédar Senghor. The word can still be used as a synonym of "sweetheart" in some traditional Louisiana French creole songs.[40] The word nègre as a racial term fell out of favor around the same time as its English equivalent negro. Its usage in French today (nègre littéraire) has shifted completely, to refer to a ghostwriter (écrivain fantôme), i.e. one who writes a book on behalf of its nominal author, usually a non-literary celebrity. However, French Ministry of Culture guidelines (as well as other official entities of Francophone regions[41]) recommend the usage of alternative terms.

Haitian Creole

In Haitian Creole, the word nèg (derived from the French nègre referring to a dark-skinned man), can also be used for any man, regardless of skin color, roughly like the terms "guy" or "dude" in American English.

Germanic languages

The Dutch word neger was considered to be a neutral term, but since the start of the 21st century it is increasingly considered to be hurtful, condescending and/or discriminatory. The consensus among language advice services of the Flemish Government and Dutch Language Union is to use zwarte persoon/man/vrouw (black person/man/woman) to denote race instead.[42][43][44][45]

In German, Neger was considered to be a neutral term for black people, but gradually fell out of fashion since the 1970s in Western Germany, where Neger is now mostly thought to be derogatory or racist. In the former German Democratic Republic, parallel to the situation in Russia, the term was not considered offensive.[46][47][48][49]

In Denmark, usage of neger is up for debate. Linguists and others argue that the word has a historical racist legacy that makes it unsuitable for use today. Mainly older people use the word neger with the notion that it is a neutral word paralleling "negro". Relatively few young people use it, other than for provocative purposes in recognition that the word's acceptability has declined.[50]

In Swedish and Norwegian, neger used to be considered a neutral equivalent to "negro". However, the term gradually fell out of favor between the late 1960s and 1990s.

Elsewhere

In the Finnish language the word neekeri (cognate with negro) was long considered a neutral equivalent for "negro".[51] In 2002, neekeri's usage notes in the Kielitoimiston sanakirja shifted from "perceived as derogatory by some" to "generally derogatory".[51] The name of a popular Finnish brand of chocolate-coated marshmallow treats was changed by the manufacturers from Neekerinsuukko (lit. 'negro's kiss', like the German version) to Brunbergin suukko ('Brunberg's kiss') in 2001.[51] A study conducted among native Finns found that 90% of research subjects considered the terms neekeri and ryssä among the most derogatory epithets for ethnic minorities.[52]

In Turkish, zenci is the closest equivalent to "negro". The appellation was derived from the Arabic zanj for Bantu peoples. It is usually used without any negative connotation.

In Hungarian, néger (possibly derived from its German equivalent) is still considered to be the most neutral equivalent of "negro".[53]

In Russia, the term негр (negr) was commonly used in the Soviet period without any negative connotation, and its use continues in this neutral sense. In modern Russian media, negr is used somewhat less frequently. Chyorny as an adjective is also used in a neutral sense, and conveys the same meaning as negr, as in чёрные американцы (chyornye amerikantsy, "black Americans"). Other alternatives to negr are темнокожий (temnokozhy, "dark-skinned"), чернокожий (chernokozhy, "black-skinned"). These two are used as both nouns and adjectives. See also Afro-Russian.

See also

- Free Negro

- Kaffir (racial term)

- Nigger

- Negrito

- Colored

- Blackfella

- Nigga

- Magical Negro, a trope in fiction

- The Book of Negroes, a historical document

References

- "Negro: definition of Negro in Oxford dictionary (British & World English)". Oxforddictionaries.com. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- Thatcher, Oliver. "Vasco da Gama: Round Africa to India, 1497-1498 CE". Modern History Sourcebook. Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- "Vasco da Gama's Voyage of 'Discovery' 1497". South African History Online. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. 2000. p. 2039. ISBN 0-395-82517-2.

- Mann, Stuart E. (1984). An Indo-European Comparative Dictionary. Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag. p. 858. ISBN 3-87118-550-7.

- "Queen Charlotte of Britain". pbs.org. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- Nguyen, Elizabeth. "Origins of Black History Month," Spartan Daily, Campus News. San Jose State University. 24 February 2004. Accessed 12 April 2008. Archived 2 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "6 Shocking Facts About Slavery, Natives and African Americans". Indian Country Today Media Network. 9 October 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- O'Neall, John Belton. "The Negro Law of South Carolina". Internet Archive. Printed by J.G. Bowman. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- Smith, Tom W. (1992) "Changing racial labels: from 'Colored' to 'Negro' to 'Black' to 'African American'." Public Opinion Quarterly 56(4):496–514

- Liz Mazucci, "Going Back to Our Own: Interpreting Malcolm X’s Transition From 'Black Asiatic' to 'Afro-American'", Souls 7(1), 2005, pp. 66–83.

- Christopher H. Foreman, The African-American predicament, Brookings Institution Press, 1999, p.99.

- "UNCF New Brand". Uncf.org. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- Quenqua, Douglas (17 January 2008). "Revising a Name, but Not a Familiar Slogan". New York Times.

- U.S. Census Bureau interactive form, Question 9. Accessed 7 January 2010. Archived 8 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- CBS New York Local News. Accessed 7 January 2010. Archived 9 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "Census Bureau defends 'negro' addition". UPI. 6 January 2010. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- Mcfadden, Katie; Mcshane, Larry (6 January 2010). "Use of word Negro on 2010 census forms raises memories of Jim Crow". Daily News. New York.

- "Segregation on buses ruled unconstitutional in 1956". NY Daily News. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

Negroes" (http://assets.nydailynews.com/polopoly_fs/1.2428061.1447081601!/img/httpImage/image.jpg_gen/derivatives/article_1200/segregation7a-1-web.jpg) replaced by "[African Americans]

- Tannenbaum, Jessie; Valcke, Anthony; McPherson, Andrew (1 May 2009). "Analysis of the Aliens and Nationality Law of the Republic of Liberia". Rochester, NY. SSRN 1795122. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - American Bar Association (May 2009). "ANALYSIS OF THE ALIENS AND NATIONALITY LAW OF THE REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA" (PDF). ABA Rule of Law Initiative.

- "negro" in the Diccionario de la Real Academia Española

- Rondilla, Joanne Laxamana (2012). Colonial Faces: Beauty and Skin Color Hierarchy in the Philippines and the U.S. (PDF) (PhD). University of California, Berkeley.

- Manalansan IV, Martin F. (2003). Global Divas. Duke University Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780822385172.

- del Castillo, Clem (22 October 2015). "A closer look at our indigenous people". SunStar Philippines. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- Snow, Philip. The Star Raft: China's Encounter With Africa. Cornell Univ. Press, 1989 (ISBN 0801495830)

- Catherine Hill; Pedro Soares; Maru Mormina; Vincent Macaulay; William Meehan; James Blackburn; Douglas Clarke; Joseph Maripa Raja; Patimah Ismail; David Bulbeck; Stephen Oppenheimer; Martin Richards (2006), "Phylogeography and Ethnogenesis of Aboriginal Southeast Asians" (PDF), Molecular Biology and Evolution, Oxford University Press, 23 (12): 2480–91, doi:10.1093/molbev/msl124, PMID 16982817, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2008

- Chaubey, Gyaneshwer; Endicott, Phillip (1 February 2013). "The Andaman Islanders in a regional genetic context: reexamining the evidence for an early peopling of the archipelago from South Asia". Human Biology. 85 (1–3): 153–172. doi:10.3378/027.085.0307. ISSN 1534-6617. PMID 24297224.

- Accademia della Crusca, Nero, negro e di colore, 12 ottobre 2012 [IT]

- "'Negro'? Per noi è dispregiativo" ("'Negro'? For us it is a derogatory term") by Beppe Severgnini, Corriere Della Sera, 13 May 2013 (in Italian)

- "...the most banned word in the politically correct dictionary..." : From "La Kyenge sdogana la parola tabù - Da oggi si può dire 'negro'" ("Kyenge clears the taboo word - From today we can say 'negro'") by Franco Bechis, Libero Quotidiano, 28 May 2014 (in Italian)

- See also Racism in Italy

- "Fausto Leali, il 'negro-bianco' compie 70 anni" ("Fausto Leali, the 'white negro', is 70 years old"), Corriere Brescia, 25 October 2014 (in Italian)

- "Auguri a Fausto Leali, il 'Negro Bianco' compie 70 anni" ("Felicitations to Fausto Leali, the 'White Negro' is 70 years old"), ANSA, 25 October 2014 (in Italian)

- "Fausto Leali, i 70 anni del Negro Bianco" ("Fausto Leali, the 70 years of the White Negro"), Brescia Oggi, 25 October 2014 (in Italian)

- Criminal Code of Italy (excerpts), Legislation online

- "ECRI Rerport on Italy" by the European Commission Against Racism and Intolerance, Council of Europe, 7 June 2016

- "Dare del 'negro' è reato : lo dice la Cassazione" ("Calling out 'negro' is a crime : so says the Supreme Court") by Ivan Francese, Il Giornale, 7 October 2014 (in Italian)

- "Razzismo, la Cassazione: 'Insulti, sempre aggravante di discriminazione'" ("Racism, the Supreme Court: 'Insults are always an aggravating factor'"), Quotidiano.net, 15 July 2013

- Radio Canada, 1971, "Le Son des Français d'Amérique #3 Les Créoles, interview with Revon Reed

- E.g. "prête-plume", Office Québécois de la Langue Française (Quebec Office for the French Language), 2012 (in French)

- "Het n-woord". Ninsee

- "Standard Dictionary of the Dutch Language: neger". Van Dale (in Dutch). Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- "zwarte / neger / negerin". www.taaltelefoon.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- "neger". VRT Taal (in Dutch). Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- Müller, W. Abitur im Sozialismus, Schülernotitzen 1963-1967. Pekrul & Sohn GBR, 2016

- Hartung, T. Neger sind keine Lösung. 2-2018, last accessed 2018-02-13

- Plenzdorf, U. Die neuen Leiden des jungen W. Suhrkamp, VEB Hinstorff Verlag, 1973. ISBN 3518068008

- Soost, D. Heimkind - Neger - Pionier. Mein Leben. Rowohlt Verlag GmbH, Reinbek, 2005 ISBN 9783499616471

- Anne Ringgaard, Journalist. "Hvorfor må man ikke sige neger?". videnskab.dk. Retrieved on 2 January 2016.

- Rastas, Anna (2007). Neutraalisti rasistinen? Erään sanan politiikkaa (PDF) (in Finnish). Tampere: Tampere University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-951-44-6946-6. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- Raittila, Pentti (2002). Etnisyys ja rasismi journalismissa (PDF) (in Finnish). Tampere: Tampere University Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 951-44-5486-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- See Hungarian sources at the related Hungarian Wikipedia article

External links

| Look up negro in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Negro (archaic term). |