Linguistic purism in English

Linguistic purism in English is the preference for using words of native origin rather than foreign-derived ones. "Native" can mean "Anglo-Saxon" or it can be widened to include all Germanic words. Linguistic purism in English primarily focuses on words of Latinate and Greek origin, due to their prominence in the English language and the belief that they may be difficult to understand. While purism, in recent times, can be deliberate, the result of positions taken by educated writers, in less conscious or unconcious form it goes back to the origins of modern English, when a great store of French words was introduced following the Norman conquest of England.

In its mildest form, it merely means using existing native words instead of foreign-derived ones (such as using begin instead of commence). In a less mild form, it also involves coining new words from Germanic roots (such as wordstock for vocabulary). In a more extreme form, it also involves reviving native words which are no longer widely used (such as ettle for intend). The resulting language is sometimes called Anglish (coined by the author and humorist Paul Jennings), or Roots English (referring to the idea that it is a "return to the roots" of English). The mild form is often advocated as part of Plain English, but the more extreme form has been and is still a fringe movement; the latter can also be undertaken as a form of constrained writing.

The linguistic purism of English is discussed by David Crystal in the Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. The idea dates at least to the inkhorn term controversy of the 16th and 17th centuries. In the 19th century, writers such as Charles Dickens, Thomas Hardy and William Barnes advocated linguistic purism and tried to introduce words like birdlore for ornithology and bendsome for flexible. A notable supporter in the 20th century was George Orwell, who had a preference for plain Saxon words over complex Latin or Greek ones, and the idea continues to have advocates today.

Impact of native words

Anglo-Saxon/Germanic words are usually shorter (fewer syllables) than their French/Latinate equivalents, and as such are perceived, usually subconsciously, as more powerful than the longer words of French/Latinate origin. When Winston Churchill said that all he could offer the English people, at the outset of World War II, was "blood, sweat, and tears", the Germanic words give strength to Churchill's vision of what was to come. The names of the animals cow, pig, sheep, and deer are of Germanic origin, but the meat derived from these animals uses words of French/Latinate origin, beef, pork, mutton, and venison, revealing how, in Norman England when conquerors introduced many French words to English, who was caring for the animals (the Anglo-Saxon peasants), and who was consuming the meat (the French conquerors/aristocrats).

In legal documents, a Latinate word and its Germanic equivalent may be used together, to ensure all understand. "Last will and testament" combines a Germanic word, "will", and a Latinate word, "testament". "Law" is Germanic, but "statute" is not. Longer Latinate words such as "bureaucratic", "equivalent", "consequence", "obfuscate", "obstruction", and the like are perceived as weak, compared with short Germanic words like "clear", "strong", "right", and "true" (and also "weak" and "wrong").

At the same time, it should be kept in mind that the words for nobility are Germanic: king, queen, lord, knight. The words of our democratic governments —"constitution", "legislature", "congress", "representative", "electoral college", "democracy", "vote", "election", "senator", even "revolution"—are of French/Latinate origin.

History

Old English and Middle English

Old English adopted a small number of Greco-Roman loan words from an early period, especially in the context of Christianity (bishop, priest). From the 9th century (Danelaw) it borrowed a much larger number of Old Norse words, many for every-day terms (skull, egg, skirt).

After the Norman conquest of 1066–71, the top level of English society was replaced by people who spoke Old Norman (a dialect of Old French). It evolved into Anglo-Norman and became the language of the state. Hence, those who wished to be involved in fields such as law and governance were required to learn it (see "Law French" for example).

It was in this Middle English period that the English language borrowed a slew of Romance loan words (via Anglo-Norman) – see "Latin influence in English". However, there were a few writers who tried to withstand the overbearing influence of Anglo-Norman. Their goal was to provide literature to the English-speaking masses in their vernacular or mother tongue. This meant not only writing in English, but also taking care not to use any words of Romance origin, which would likely not be understood by the readers. Examples of this kind of literature are the Ormulum, Layamon's Brut, Ayenbite of Inwyt, and the Katherine Group of manuscripts in the "AB language".

Early Modern English

In the 16th and 17th centuries, controversy over needless foreign borrowings from Latin and Greek (known as "inkhorn terms") was rife. Critics argued that English already had words with identical meanings. However, many of the new words gained an equal footing with the native Germanic words, and often replaced them.

Writers such as Thomas Elyot flooded their writings with foreign borrowings, while writers such as John Cheke sought to keep their writings "pure". Cheke wrote:

I am of this view that our own tung should be written cleane and pure, unmixt and unmangeled with borowing of other tunges; wherein if we take not heed by tiim, ever borowing and never paying, she shall be fain to keep her house as bankrupt.

In reaction, some writers tried either to resurrect older English words, such as gleeman for musician, sicker (itself a Proto-Germanic borrowing from Latin sēcūrus) for certainly, inwit for conscience, and yblent for confused, or to make new words from Germanic roots, e.g. endsay for conclusion, yeartide for anniversary, foresayer for prophet. However, few of these words remain in common use.

Modern English

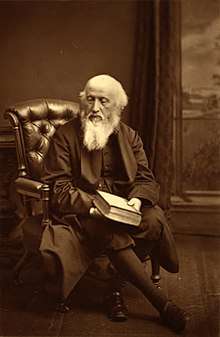

A noted advocate of English linguistic purism was 19th-century English writer, poet, minister, and philologist William Barnes, who sought to make scholarly English easier to understand without a classical education. Barnes lamented the "needless inbringing" of foreign words, instead using native words from his own dialect and coining new ones based on Old English roots. These included speechcraft for grammar, birdlore for ornithology, fore-elders for ancestors and bendsome for flexible. Another 19th-century poet who supported linguistic purism was Gerard Manley Hopkins. He wrote in 1882, "It makes one weep to think what English might have been; for in spite of all that Shakespeare and Milton have done ... no beauty in a language can make up for want of purity".[1]

In his 1946 essay "Politics and the English Language", George Orwell wrote:

Bad writers—especially scientific, political, and sociological writers—are nearly always haunted by the notion that Latin or Greek words are grander than Saxon ones.

A contemporary of Orwell, the Australian composer Percy Grainger, wrote English with only Germanic words and called it "blue-eyed English". For example, a composer became a tonesmith. He also used English terms instead of the traditional Italian ones as performance markings in his scores, e.g. louden lots instead of molto crescendo.

Lee Hollander's 1962 English translation of the Poetic Edda (a collection of Old Norse poems), written almost solely with Germanic words, would also inspire many future "Anglish" writers.

In 1966, Paul Jennings wrote three articles in Punch, to commemorate the 900th anniversary of the Norman conquest. His articles, entitled '1066 and All Saxon', published on 15, 22 and 29 June, posed the question of what England would be like had it not happened. They included an example of what he called "Anglish", such as a sample of Shakespeare's writing as it might have been if the conquest had failed. He gave "a bow to William Barnes".

In 1989, science fiction writer Poul Anderson wrote a text about basic atomic theory called Uncleftish Beholding. It was written using almost only words of Germanic origin, and was meant to show what English scientific works might look like without foreign borrowings. In 1992, Douglas Hofstadter jokingly referred to the style as "Ander-Saxon". This term has since been used to describe any scientific writings that use only Germanic words.

Anderson used techniques including:

- extension of sense (motes for 'particles');

- calques, i.e., translation of the morphemes of the foreign word (uncleft for atom, which is from Greek a- 'not' and temnein 'to cut'; ymirstuff for 'uranium', referencing Ymir, a giant in Norse mythology, whose role is similar to that of Uranus in Greek mythology);

- calques from other Germanic languages like German and Dutch (waterstuff from the German Wasserstoff / Dutch waterstof for 'hydrogen'; sourstuff from the German Sauerstoff / Dutch zuurstof for 'oxygen');

- coining (firststuff for 'element'; lightrotting for 'radioactive decay').

The first chapter of Alan Moore's 1996 novel Voice of the Fire uses mostly Germanic words.

Another approach, without a specific name-tag, can be seen in the September 2009 publication How We'd Talk if the English had Won in 1066, by David Cowley (the title referencing the Battle of Hastings). This updates Old English words to today's English spelling, and seeks mainstream appeal by covering words in five steps, from easy to "weird and wonderful", as well as giving many examples of use, drawings and tests.[2]

Paul Kingsnorth's 2014 The Wake is written in a hybrid of Old English and Modern English to account for its 1066 milieu.

Edmund Fairfax's satiric literary novel Outlaws (2017) is written in a "constructed" form of English consisting almost exclusively of words of Germanic origin, with many neologisms (e.g., kenkeen for 'curious', to enhold for 'to contain') and little-used or obsolete words transparent in meaning to the modern reader (e.g., to misfare for 'to fail', to overlive for 'to survive'), and employing alternative orthographic conventions in compounds and phrasal constructions.

See also

- Classical compound – Classical compounds and neoclassical compounds are compound words composed from combining forms (which act as affixes or stems) derived from classical Latin or ancient Greek roots

- Constrained writing

- Hermeneutic style – Style of Latin in the later Roman and early Medieval periods

- Høgnorsk – Unofficial Norwegian written standard language

- Linguistic purism in Icelandic

- List of English words of Anglo-Saxon origin – Wikipedia list article

- List of Germanic and Latinate equivalents in English – Wikipedia list article

- Plain English – Simple terms in English

- Politics and the English Language – Essay by George Orwell

Notes

- Nils Langer, Winifred V. Davies. Linguistic purism in the Germanic languages. Walter de Gruyter, 2005. p.328

- "How We'd Talk If the English Had Won in 1066". Authors Online. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013.

References

- Paul Jennings, "I Was Joking Of Course", London, Max Reinhardt Ltd, 1968

- Poul Anderson, "Uncleftish Beholding", Analog Science Fact / Science Fiction Magazine, mid-December 1989.

- Douglas Hofstadter (1995). "Speechstuff and Thoughtstuff". In Sture Allén (ed.). Of Thoughts and Words: Proceedings of Nobel Symposium 92. London: Imperial College Press. ISBN 1-86094-006-4. Includes a reprint of Anderson's article, with a translation into more standard English.

- Douglas Hofstadter (1997). Le Ton beau de Marot: In Praise of the Music of Language. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-08645-4. Also includes and discusses excerpts from the article.

- Elias Molee, "Pure Saxon English, or Americans to the Front", Rand, McNally & Company, Publishers, Chicago and New York, 1890.