Muslim rule of India

Muslim rule in the Indian subcontinent began in the course of a gradual Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinent, beginnning mainly after the conquest of Sindh and Multan led by Muhammad bin Qasim.[1] Following the perfunctory rule by the Ghaznavids in Punjab, Sultan Muhammad of Ghor is generally credited with laying the foundation of Muslim rule in the India.

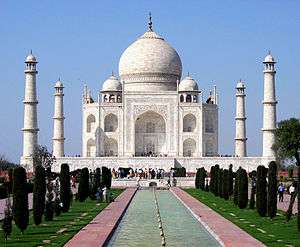

Mughal India at its height, 17th century. | |

| Date | 8th century-onwards |

|---|---|

| Location | Indian subcontinent |

| Participants | Numerous Sultanates |

| Part of a series on |

| Islam in India |

|---|

|

Administration |

|

History

|

|

Architecture |

|

Major figures

|

|

Famous Families and ethnicities

|

|

Mosques in India |

|

Influential bodies

|

From the late 12th century onwards, Turko-Mongol Muslim empires began to establish themselves throughout the subcontinent including the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal Empire, who adopted local culture and intermarried with natives.[2] Various other Muslim kingdoms, which ruled most of South Asia during the mid-14th to late 18th centuries, including the Bahmani Sultanate, Deccan Sultanates, and Gujarat Sultanate were native in origin.[3][4] Sharia was used as the primary basis for the legal system in the Delhi Sultanate, most notably during the rule of Firuz Shah Tughlaq and Alauddin Khilji, who repelled the Mongol invasions of India. While rulers such as Akbar adopted a secular legal system and enforced religious neutrality. [5]

Muslim rule in India saw a major shift in the cultural, linguistic, and religious makeup of the subcontinent.[6] Persian and Arabic vocabulary began to enter local languages, giving way to modern Punjabi, Bengali, and Gujarati, while creating new languages including Urdu and Deccani, used as official languages under Muslim dynasties, and Hindi.[7] This period also saw the birth of Hindustani music, Qawwali and the further development of dance forms such as Kathak.[8][9] Religions such as Sikhism and Din-e-Ilahi were born out of a fusion of Hindu and Muslim religious traditions as well.[10]

The height of Islamic rule was marked during the reign of Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, during which the Fatawa Alamgiri was compiled, which briefly served as the legal system of Mughal India.[11] Additional Islamic policies were re-introduced in South India by the Mysore King Tipu Sultan.[12]

The eventual end of the period of Muslim rule of modern India is mainly marked with the beginning of British rule, although its aspects persisted in Hyderabad State, Junagadh State, Jammu and Kashmit State and other minor princely states until the mid of the 20th century. Today's modern Bangladesh, Maldives and Pakistan remain the only Muslim majority nations in the Indian subcontinent.

Early Muslim dominion

Local Muslim revert kings existed in places such as Kerala, Gujarat, Ceylon (Sri Lanka) as early as in the 7th century. Remarkable Islamic rules in India prior to the advent of the Mamluk dynasty (Delhi) include those of Umayyad Caliphate's Muhammad bin Qasim, Ghaznavids and Ghurids.

Delhi Sultanate

During the last quarter of the 12th century, Muhammad of Ghor invaded the Indo-Gangetic plain, conquering in succession Ghazni, Multan, Sindh, Lahore, and Delhi. Qutb-ud-din Aybak, one of his generals proclaimed himself Sultan of Delhi. In Bengal and Bihar, the reign of general Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khalji was established, where the missionaries of the Islamic faith accomplished their biggest success in terms of dawah and number of converts to Islam. In the 13th century, Shamsuddīn Iltutmish (1211–1236), established a Turkic kingdom in Delhi, which enabled future sultans to push in every direction; within the next 100 years, the Delhi Sultanate extended its way east to Bengal and south to the Deccan, while the sultanate itself experienced repeated threats from the northwest and internal revolts from displeased, independent-minded nobles. The sultanate was in constant flux as five dynasties, all of either Turkic or Afghan origin,[13] rose and fell: the Slave dynasty (1206–90), Khalji dynasty (1290–1320), Tughlaq dynasty (1320–1413), Sayyid dynasty (1414–51), and Lodi dynasty (1451–1526). The Khalji dynasty, under 'Alā'uddīn (1296–1316), succeeded in bringing most of South India under its control for a time, although conquered areas broke away quickly. Power in Delhi was often gained by violence—nineteen of the thirty-five sultans were assassinated—and was legitimized by reward for tribal loyalty. Factional rivalries and court intrigues were as numerous as they were treacherous; territories controlled by the sultan expanded and shrank depending on his personality and fortunes.

Both the Qur'an and sharia (Islamic law) provided the basis for enforcing Islamic administration over the independent Hindu rulers, but the sultanate made only fitful progress in the beginning when many campaigns were undertaken for plunder and temporary reduction of fortresses. The effective rule of a sultan depended largely on his ability to control the strategic places that dominated the military highways and trade routes, extract the annual land tax, and maintain personal authority over military and provincial governors. Sultan 'Ala ud-Din made an attempt to reassess, systematize, and unify land revenues and urban taxes and to institute a highly centralized system of administration over his realm, but his efforts were abortive. Although agriculture in North India improved as a result of new canal construction and irrigation methods, including what came to be known as the Persian wheel, prolonged political instability and parasitic methods of tax collection brutalized the peasantry. Yet trade and a market economy, encouraged by the free-spending habits of the aristocracy, acquired new impetus both in and overseas. Experts in metalwork, stonework, and textile manufacture responded to the new patronage with enthusiasm. In this period Persian language and many Persian cultural aspects became dominant in the centers of power in Meric'a, as the rulers of the Delhi Sultanate (who, though being Turkish or Afghan, had been thoroughly Persianized since the era of the Ghaznavids)[14] patronized aspects of the foreign culture and language from their seat of power in India.

Bengal Sultanate

In 1339, the Bengal region became independent from the Delhi Sultanate and consisted of numerous Islamic city-states. The Bengal Sultanate was formed in 1352 after Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah, ruler of Satgaon, defeated Alauddin Ali Shah of Lakhnauti and Ikhtiyaruddin Ghazi Shah of Sonargaon; ultimately unifying Bengal into one single independent Sultanate. At its greatest extent, the Bengal Sultanate's realm and protectorates stretched from Jaunpur in the west, Tripura and Arakan in the east, Kamrup and Kamata in the north and Puri in the south.

Although a Sunni Muslim monarchy ruled by Turco-Persians, Bengali Muslims, Habshis, and Arabs, they still employed many non-Muslims in the administration and promoted a form of religious pluralism.[15][16] It was known as one of the major trading nations of the medieval world, attracting immigrants and traders from different parts of the world.[17] Bengali ships and merchants traded across the region, including in Malacca, China, Africa, Europe and the Maldives through maritime links and overland trade routes. Contemporary European and Chinese visitors described Bengal as the "richest country to trade with" due to the abundance of goods in Bengal. In 1500, the royal capital of Gaur was the fifth-most populous city in the world with 200,000 residents.[18][19]

Persian was used as a diplomatic and commercial language. Arabic was the liturgical language of the clergy, and the Bengali language became a court language.[20] Bengali was patronised by the Sultans and saved it from being corrupted by the Brahmins wishing to Sanskritise it.[21] Sultan Ghiyathuddin Azam Shah sponsored the construction of madrasas in Makkah and Madinah.[22] The schools became known as the Ghiyasia Banjalia Madrasas. Taqi al-Din al-Fasi, a contemporary Arab scholar, was a teacher at the madrasa in Makkah. The madrasa in Madinah was built at a place called Husn al-Atiq near the Prophet's Mosque.[23] Several other Bengali Sultans also sponsored madrasas in the Hejaz.[24]

The Karrani dynasty was the last ruling dynasty of the sultanate. The Mughals became determined to bring an end to Bengali imperialism. Mughal rule formally began with the Battle of Rajmahal in 1576, when the last Sultan Daud Khan Karrani was defeated by the forces of Emperor Akbar, and the establishment of the Bengal Subah. The eastern deltaic Bhati region remained outside of Mughal control until being absorbed in the early 17th century. The delta was controlled by a confederation of aristocrats of the Sultanate, who became known as the Baro-Bhuiyans. The Mughal government eventually suppressed the remnants of the Sultanate and brought all of Bengal under full Mughal control.

Southern dynasties

The sultans' failure to hold securely the Deccan and South India resulted in the rise of competing for Southern dynasties: the Muslim Bahmani Sultanate (1347–1527) and the Hindu Vijayanagara Empire (1336–1565). Zafar Khan, a former provincial governor under the Tughluqs, revolted against his Turkic overlord and proclaimed himself sultan, taking the title Ala-ud-Din Bahman Shah in 1347. The Bahmani Sultanate, located in the northern Deccan, lasted for almost two centuries, until it fragmented into five smaller states, known as the Deccan sultanates (Bijapur, Golconda, Ahmednagar, Berar, and Bidar) in 1527. The Bahmani Sultanate adopted the patterns established by the Delhi overlords in tax collection and administration, but its downfall was caused in large measure by the competition and hatred between Deccani (domiciled Muslim immigrants and local converts) and paradesi (foreigners or officials in temporary service). The Bahmani Sultanate initiated a process of cultural synthesis visible in Hyderabad where cultural flowering is still expressed in vigorous schools of Deccani architecture and painting.

Founded in 1336, the Vijayanagara Empire (named for its capital Vijayanagara (Vijayanagar), "City of Victory," in present-day Karnataka) expanded rapidly toward Madurai in the south and Goa in the west and exerted intermittent control over the east coast and the extreme southwest. Vijayanagara rulers closely followed Chola precedents, especially in collecting agricultural and trade revenues, in giving encouragement to commercial guilds, and in honoring temples with lavish endowments. Added revenue needed for waging war against the Bahmani sultans was raised by introducing a set of taxes on commercial enterprises, professions, and industries. Political rivalry between the Bahmani and the Vijayanagara rulers involved control over the Krishna-Tungabhadra river basin, which shifted hands depending on whose military was superior at any given time. The Vijayanagar rulers' capacity for gaining victory over their enemies was contingent on ensuring a constant supply of horses—initially through Arab traders but later through the Portuguese—and maintaining internal roads and communication networks. Merchant guilds enjoyed a wide sphere of operation and were able to offset the power of landlords and Brahmans in court politics. Commerce and shipping eventually passed largely into the hands of foreigners, and special facilities and tax concessions were provided for them by the ruler.

The city of Vijayanagara itself contained numerous temples with rich ornamentation, especially the gateways, and a cluster of shrines for the deities. Most prominent among the temples was the one dedicated to Virupaksha, a manifestation of Shiva, the patron-deity of the Vijayanagar rulers. Temples continued to be the nuclei of diverse cultural and intellectual activities, but these activities were based more on tradition than on contemporary political realities. When the rulers of the five Deccan sultanates combined their forces and attacked Vijayanagara in 1565, the empire crumbled at the Battle of Talikot. Most Muslim rulers of south India were Shia muslims.[25]

Mughal era

The Mughal Empire ruled most of the Indian subcontinent between 1526 and 1707. The empire was founded by the Turco-Mongol leader Babur in 1526, when he defeated Ibrahim Lodi, the last Pashtun ruler of the Delhi Sultanate at the First Battle of Panipat. The word "Mughal" is the Persian version of Mongol. Babur, Humayun, Akbar, Jahangir, Shah Jahan, Aurangzeb are known as the six great Mughal Emperors.

Hyderabad Nizam

Nizam, a shortened version of Nizam-ul-Mulk, meaning Administrator of the Realm, was the title of the native sovereigns of Hyderabad state, India, since 1719, belonging to the Asaf Jah dynasty. The dynasty was founded by Mir Qamar-ud-Din Siddiqi, a viceroy of the Deccan under the Mughal emperors from 1713 to 1721 who intermittently ruled under the title Asaf Jah in 1924. After Aurangzeb's death in 1707, the Mughal Empire crumbled, and the viceroy in Hyderabad, the young Asaf Jah, declared himself independent.

Other Islamic rulers

Nawab of Awadh ruled parts of current day Uttar Pradesh. Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan briefly held power in Mysore kingdom. Many princely states other than Hyderabad had Muslim rulers.

See also

- The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. The Muhammadan Period (Book)

- Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinent

- History of India

References

- Some Aspects of Muslim Administration, Dr. R.P.Tripathi, 1956, p.24

- Noah), Abu Noah Ibrahim Ibn Mika'eel Jason Galvan (Abu; Galvan, Jason (2008-09-30). Art Thou That Prophet?. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-0-557-00033-3.

- Syed, Muzaffar Husain; Akhtar, Syed Saud; Usmani, B. D. (2011-09-14). Concise History of Islam. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. ISBN 978-93-82573-47-0.

- Stanley Lane-Poole (1 January 1991). Aurangzeb And The Decay Of The Mughal Empire. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors (P) Limited. ISBN 978-81-7156-017-2.

- Madan, T. N. (2011-05-05). Sociological Traditions: Methods and Perspectives in the Sociology of India. SAGE Publications India. ISBN 978-81-321-0769-9.

- Avari, Burjor (2013). Islamic Civilization in South Asia: A History of Muslim Power and Presence in the Indian Subcontinent. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-58061-8.

- Khan, Abdul Jamil (2006). Urdu/Hindi: An Artificial Divide: African Heritage, Mesopotamian Roots, Indian Culture & Britiah Colonialism. Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-438-9.

- Goldberg, K. Meira; Bennahum, Ninotchka Devorah; Hayes, Michelle Heffner (2015-10-06). Flamenco on the Global Stage: Historical, Critical and Theoretical Perspectives. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-9470-5.

- Lavezzoli, Peter (2006-04-24). The Dawn of Indian Music in the West. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-8264-1815-9.

- Oberst, Robert (2018-04-27). Government and Politics in South Asia, Student Economy Edition. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-97340-6.

- Chapra, Muhammad Umer (2014). Morality and Justice in Islamic Economics and Finance. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 62–63. ISBN 9781783475728.

- B. N. Pande (1996). Aurangzeb and Tipu Sultan: Evaluation of Their Religious Policies. University of Michigan. ISBN 9788185220383.

- Gat, Azar (2013). Nations: The Long History and Deep Roots of Political Ethnicity and Nationalism. Cambridge University Press. p. 126. ISBN 9781107007857.

- "South Asian Sufis: Devotion, Deviation, and Destiny". Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- "Gaur and Pandua Architecture". Sahapedia.

- "He founded the Bengali Husayn Shahi dynasty, which ruled from 1493 to 1538, and was known to be tolerant to Hindus, employing many on them in his service and promoting a form of religious pluralism" David Lewis (31 October 2011). Bangladesh: Politics, Economy and Civil Society. Cambridge University Press. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-1-139-50257-3.

- Richard M. Eaton (31 July 1996). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760. University of California Press. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-0-520-20507-9.

- Bar chart race: the most populous cities through time, retrieved 2019-12-22

- Kapadia, Aparna. "Gujarat's medieval cities were once the biggest in the world – as a viral video reminds us". Scroll.in. Retrieved 2019-12-22.

- "Evolution of Bangla". The Daily Star. 2019-02-21. Retrieved 2019-12-31.

- Muhammad Mojlum Khan (21 Oct 2013). The Muslim Heritage of Bengal: The Lives, Thoughts and Achievements of Great Muslim Scholars, Writers and Reformers of Bangladesh and West Bengal. Kube Publishing Ltd. p. 37.

- Richard M. Eaton (31 July 1996). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760. University of California Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-520-20507-9. Archived from the original on 6 January 2017.

- Abdul Karim. "Ghiyasia Madrasa". Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- "Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 7 July 2015.

- Negationism in India Concealing the record of Islam By Koenraad Elst

Literature

- Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra; Pusalker, A. D.; Majumdar, A. K., eds. (1960). The History and Culture of the Indian People. VI: The Delhi Sultanate. Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

- Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra; Pusalker, A. D.; Majumdar, A. K., eds. (1973). The History and Culture of the Indian People. VII: The Mughal Empire. Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

- Elliot, Sir H. M., Edited by Dowson, John. The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. The Muhammadan Period; published by London Trubner Company 1867–1877. (Online Copy: The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. The Muhammadan Period; by Sir H. M. Elliot; Edited by John Dowson; London Trubner Company 1867–1877 - This online Copy has been posted by: The Packard Humanities Institute; Persian Texts in Translation; Also find other historical books: Author List and Title List)