Murshidabad

Murshidabad (Pron: ˈmʊəʃɪdəˌbɑ:d/bæd or ˈmɜ:ʃɪdəˌ)[lower-alpha 1] is a town in the Indian state of West Bengal. It is located on the eastern bank of the Hooghly River, a distributary of the Ganges River. It forms part of the Murshidabad district.

Murshidabad | |

|---|---|

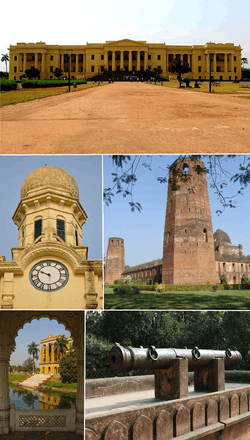

Clockwise from top: Hazarduari Palace, Caravanserai of Murshidabad, Jahan Kosha Cannon, Kathgola, Murshidabad Clock Tower | |

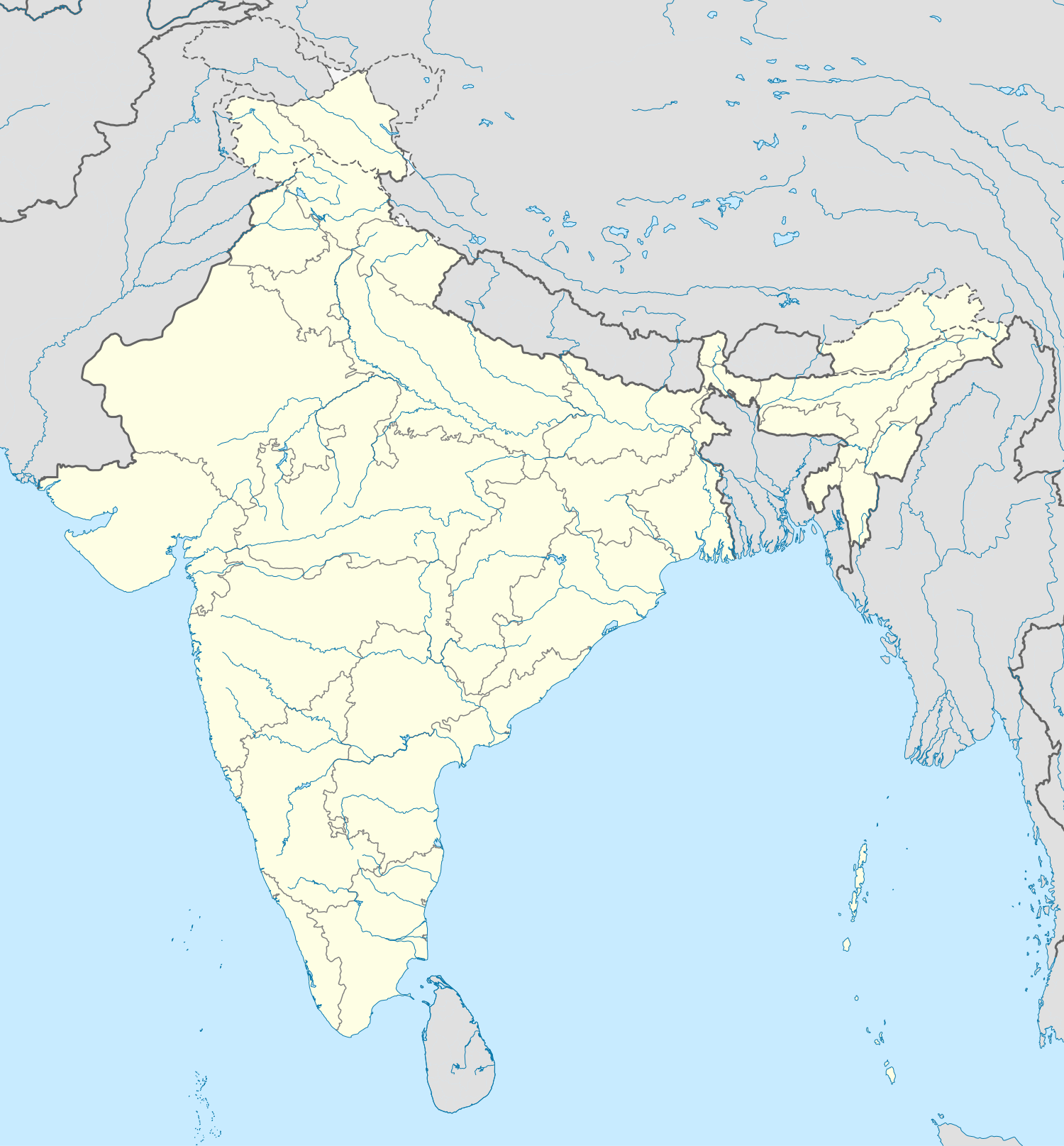

Murshidabad Location in West Bengal, India  Murshidabad Murshidabad (India) | |

| Coordinates: 24.18°N 88.27°E | |

| Country | |

| State | West Bengal |

| District | Murshidabad |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipality |

| • Body | Murshidabad Municipality |

| Elevation | 10 m (30 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 44,019 |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Bengali[2][3] |

| • Additional official | English[2] |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| PIN | 742149 |

| Telephone code | 91-3482-2xxxxx |

| Vehicle registration | WB-58 |

| Lok Sabha constituency | Murshidabad |

| Vidhan Sabha constituency | Murshidabad |

| Website | murshidabad |

During the 18th-century, Murshidabad was a prosperous city.[4][5] It was the capital of the Bengal Subah in the Mughal Empire for seventy years, with a jurisdiction covering modern-day Bangladesh and the Indian states of West Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. It was the seat of the hereditary Nawab of Bengal and the state's treasury, revenue office and judiciary. Bengal was the richest Mughal province. Murshidabad was a cosmopolitan city. Its population peaked at 700,000 in the 1750s. It was home to wealthy banking and merchant families from different parts of the Indian subcontinent and wider Eurasia, including the Jagat Seth and Armenians.

European companies, including the British East India Company, the French East India Company, the Dutch East India Company and the Danish East India Company, conducted business and operated factories around the city. Silk was a major product of Murshidabad. The city was also a center of art and culture, including for ivory sculptors, Hindustani classical music and the Murshidabad style of Mughal painting.

The city's decline began with the defeat of the last independent Nawab of Bengal Siraj-ud-Daulah at the Battle of Plassey in 1757. The Nawab was demoted to the status of a zamindar known as the Nawab of Murshidabad. The British shifted the treasury, courts and revenue office to Calcutta. In the 19th century, the population was estimated to be 46,000. Murshidabad became a district headquarters of the Bengal Presidency. It was declared as a municipality in 1869.

Etymology

Murshidabad was named after its founder, Nawab Murshid Quli Khan. Murshid is an Arabic term for a teacher or guide with integrity, sensibility, and maturity. The suffix -abad is derived from the Persian word abad, which referred to a cultivated place.

History

.jpg)

The area was part of the Gauda Kingdom and Vanga Kingdom in ancient Bengal. The Riyaz-us-Salatin credited the initial development of the town to a merchant named Makhsus Khan. The merchant's role is also mentioned in the Ain-i-Akbari.[6]

During the 17th-century, the area was well known for sericulture. In 1621, English agents reported that large quantities of silk were available in the area. During the 1660s, it became a pargana of the Mughal administration, with jurisdiction over European companies in Cossimbazar.[6]

In the early 18th-century, Murshid Quli Khan, the prime minister of Bengal Subah, had a bitter rivalry with Prince Azim-ush-Shan, the viceroy of Bengal. The latter even attempted to have Khan killed.[6] The Mughal court in Delhi was also rapidly losing authority in much of the subcontinent. Amid the decline of the central government, the Mughal Emperor Farrukhsiyar promoted Khan to the status of a princely Nawab. As Nawab, Khan was given the opportunity to create a princely dynasty as part of the Mughal aristocracy.

Murshid Quli Khan shifted the capital of Bengal from Dhaka, which lost its strategic importance after the expulsion of the Arakanese and Portuguese from Chittagong.[6] He founded the city of Murshidabad and named the city after himself. It became the center of political, economic and cultural life in Bengal. The jurisdiction of the Nawab included not only Bengal, but also Bihar and Orissa.[7] Murshidabad was also located centrally in the expanded jurisdiction of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa.

The presence of the princely court, the Mughal Army, artisans and multiethnic merchants increased the wealth of Murshidabad. Wealthy families and companies established their head offices in the city. The Murshidabad mint became the largest in Bengal, with a value amounting to two percent of the minted currency. The city witnessed the construction of administrative buildings, gardens, palaces, mosques, temples and mansions. European companies operated factories in the city's outskirts. The city was full of brokers, workers, peons, naibs, wakils, and ordinary traders.[6]

Murshid Quli Khan transformed Murshidabad into a capital city with an efficient administrative machinery for his successors. He built a palace and a caravanserai with a grand mosque, known as the Katra Masjid. The main military base was located near the mosque and formed the city's eastern gateway. The third Nawab Shuja-ud-Din Muhammad Khan patronized the construction of another palace and military base, a new gateway, the revenue office, a public audience hall (durbar), a private chamber, the treasury and a mosque in an extensive compound called Farrabagh (Garden of Joy) which included canals, fountains, flowers, and fruit trees.[6]

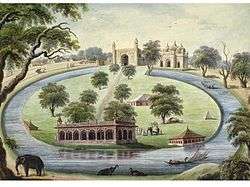

Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah established a palace near the Motijhil (Pearl Lake). The Nizamat Imambara was built for Shia Muslims. The palace complex was fortified and known as the Nizamat Fort. The main entrances of the Nizamat Fort had musicians' galleries. The gates were high, imposing and tall enough for an elephant to pass through. The Khoshbagh garden was the burial place of the Nawabs.[6] The city had a Bengali majority population, including Bengali Muslims and Bengali Hindus. There was an influential Jain community involved in trade and commerce.[7] An Armenian community also settled and became financiers for the Nawab. The Jagat Seth were one of the prominent banking families of Murshidabad. They controlled money lending activities and served as financiers for administrators, merchants, traders, the Nawabs, the Zamindars, as well as the British, French, Armenians and Dutch. The merchants built many mansions, including the Azimganj Rajbati, Kathgola house and Nashipur house.

The Nawabs of Bengal entered into agreements with numerous European trading companies allowing them to establish bases in the region. The French East India Company operated factories in Murshidabad and Dhaka. The British East India Company was based in Fort William. Murshidabad was a part of the Dutch Bengal Department. The Ostend Company of Austria established a base near Murshidabad. The Danish East India Company also set up trading posts in the Bengal Subah.

The last independent Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah was overthrown in 1757. Despite receiving assurances of French support, the Nawab was betrayed by his commander Mir Jafar. The British installed Mir Jafar's family as a puppet dynasty and eventually reduced the Nawab to the status of a landlord (zamindar). The British continued to collect revenue from the area's factories. The merchant families continued to prosper under company rule in India.[7] In 1858, the British government gained direct control of India's administration.

Murshidabad was a district town of the Bengal Presidency. Warren Hastings removed the supreme civil and criminal courts to Calcutta in 1772, but in 1775 the latter courts were brought back to Murshidabad again. In 1790, under Lord Cornwallis, the entire revenue and judicial staffs were moved to Calcutta. The town was still the residence of the Nawab, who ranked as the first nobleman of the province with the style of Nawab Bahadur of Murshidabad, instead of Nawab Nazim of Bengal. The Hazarduari Palace was built in 1837 as a residence for both the Nawab and British civil servants. Murshidabad became a municipality in 1869. The population in 1901 was 15,168. The silk industry was revived with assistance from the government. The area also became notable for mango and litchi production.[8]

- Art of Murshidabad

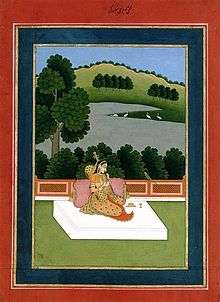

Two horsemen, Murshidabad style of painting

Two horsemen, Murshidabad style of painting Woman playing the sitar, Murshidabad style of painting

Woman playing the sitar, Murshidabad style of painting Ivory sculpture of a royal barge

Ivory sculpture of a royal barge Ivory sculpture of a royal barge

Ivory sculpture of a royal barge- An elevated musicians' gallery where drums, flutes and Indian classical music would be played.

Geography

The District of Murshidabad has an area of 5,550 square kilometres (2,140 sq mi). It is divided into two nearly equal portions by the Bhagirathi, the ancient channel of the Ganges. The tract to the west, known as the Rarh, consists of hard clay and nodular limestone. The general level is high, but interspersed with marshes and seamed by hill torrents. The Bagri or eastern half belongs to alluvial plains of eastern Bengal. There are few permanent swamps; but the whole country is low-lying, and liable to annual inundation. In the north-west are a few small detached hillocks, said to be of basaltic formation.[9]

Economy

The city today is a center for agriculture, handicrafts and sericulture. The famous Murshidabad Silk, much in demand for making saris and scarves, is produced here.

Demographics

As of 2011 Indian Census, Murshidabad had a total population of 44,019, of which 22,177 were males and 21,842 were females. Population within the age group of 0 to 6 years was 4,414. The total number of literates in Murshidabad was 32,451, which constituted 73.7% of the population with male literacy of 77.3% and female literacy of 70.1%. The effective literacy rate of 7+ population of Murshidabad was 81.9%, of which male literacy rate was 86.0% and female literacy rate was 77.9%. The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes population was 13,762 and 302 respectively. Murshidabad had 9829 households in 2011.[1]

Educational institutes

Schools

- Sargachi Ramakrishna Mission High School, Sargachi

- Ahiran Hemangini Vidyaytan School (H.S.), Ahiran, Suti I, Murshidabad

Colleges

Universities

Places of interest

Of historic interest are Nizamat Kila (the Fortress of the Nawabs), also known as the Hazaarduari Palace (Palace of a Thousand Doors), built by Duncan McLeod of the Bengal Engineers in 1837, in the Italianate style, the Moti Jhil (Pearl Lake) just to the south of the palace, the Muradbagh Palace and the Khushbagh Cemetery, where the remains of Ali Vardi Khan and Siraj Ud Daulah are interred.

Hazarduari Palace is located in the campus of Kila Nizamat of Murshidabad. It was built in the nineteenth century by architect Duncan Macleod, under the reign of Nawab Nazim Humayun Jah of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa (1824–1838). The foundation stone of the palace was laid on 9 August 1829, and that very day the construction work was started. William Cavendish was the then Governor-General. Now, Hazarduari Palace is the most conspicuous building in Murshidabad. In 1985, the palace was handed over to the Archaeological Survey of India for better preservation.

The present Nizamat Imambara was built in 1847 AD by Nawab Nazim Mansoor Ali Khan Feradun Jah, who succeeded his father Nawab Nazim Humayun Jah in Murshidabad, India. It was built after the fires of 1842 and 1846 which burnt the wooden Imambara built by Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah. This Imambara is the largest one in India and Bengal.

The Katra Masjid (also known as Katra Mosque) is a mosque and the tomb of Nawab Murshid Quli Khan built between 1723 and 1724. It is located in the north eastern side of the city. Its importance lies not only as a great centre of Islamic learning but also for the tomb of Murshid Quli Khan, who is buried under the entrance staircase. The most striking feature is the two large corner towers having loopholes for musketry. At present it is maintained and protected by the Archaeological Survey of India and the Government of West Bengal.

Bacchawali Tope is a gun, rather cannon which lies in the Nizamat Fort Campus on the garden space between the Nizamat Imambara and the Hazarduari Palace and to the east of the old Madina Mosque. The cannon consists two pieces of different diameters. The cannon was made between the 12th and 14th century, probably by the Mohammeddan rulers of Gaur. It originally lied on the sand banks of Ichaganj. However, it is unknown that how it came in Ichaganj. It was used to protect the city of Murshidabad from north-western attacks. After the 1846 fire of the Nizamat Imambara the Imambara was rebuilt, then after the completion of the new Imambara the cannon was shifted to its present site by Sadeq Ali Khan, the architect of the sacred Nizamat Imambara under the suggestion of Sir Henry Torrens, the then agent of the Governor General at Murshidabad.

Notable residents

- Nawabs

- Murshid Kuli Khan

- Iskander Mirza

- Siraj ud-Daulah

- Literature

- Manish Ghatak

- Mahasweta Devi

- Rakhaldas Bandyopadhyay

- Sarat Chandra Pandit

- Ramendra Sundar Tribedi

- Syed Mustafa Siraj

- Arup Chandra

- Govindadasa

- Abul Bashar

- Nabarun Bhattacharya

- Nirupama Devi

- Music, painting and performing arts

- Shreya Ghoshal

- Arijit Singh

- Mir Afsar Ali

- Abdul alim

- Amiya Kumar Bagchi

- Abul Hayat

- Farida Yasmin

- Tapan Sinha

- Basu Bhattacharya

- Freedom fighters

- Sportsmen

Notes

- Earlier European spellings include Muxadavad, Murshedabud, Murshedabad, Murshedebad, Murshidabud, Murshidabad, Murshidebad, Mursedabad, Mursidabud, Mursidabad, Moorshedabud, Moorshedabad, Moorshedebad, Moorshidabad, Moorsedabad, Moorsidabad, Mourshedabad, Mourshedebad, Mourshidabad, Murschidabad, Murschedabad, Moorschedabad, and Moorschidabad, among others.

References

- "Census of India: Murshidabad". www.censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- "Fact and Figures". Wb.gov.in. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- "52nd REPORT OF THE COMMISSIONER FOR LINGUISTIC MINORITIES IN INDIA" (PDF). Nclm.nic.in. Ministry of Minority Affairs. p. 85. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- William Dalrymple (10 September 2019). The Anarchy: The East India Company, Corporate Violence, and the Pillage of an Empire. Bloomsbury USA. ISBN 978-1-63557-395-4.

- https://www.thedailystar.net/op-ed/politics/which-india-claiming-have-been-colonised-119284

- "Murshidabad - Banglapedia". Banglapedia. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- Silliman, Jael (28 December 2017). "Murshidabad can teach the rest of India how to restore heritage and market the past". Scroll.in. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- "Mango people of murshidabad". The Telegraph. India. 18 June 2015. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

-

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Murshidabad. |

- District website