Bari

Bari (/ˈbɑːri/ BAR-ee, Italian: [ˈbaːri] (![]()

Bari | |

|---|---|

| Comune di Bari | |

A collage of Bari, Top left: Swabian Castle, Top right: Night in Pane e Pomodoro Beach, Bottom left: Ferrarese Square, Bottom upper right: Bari University in Andrea da Bari street, Bottom lower right: View of Punta Perotti seaside area | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

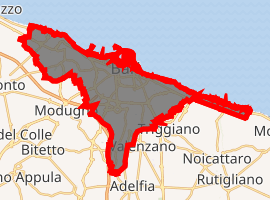

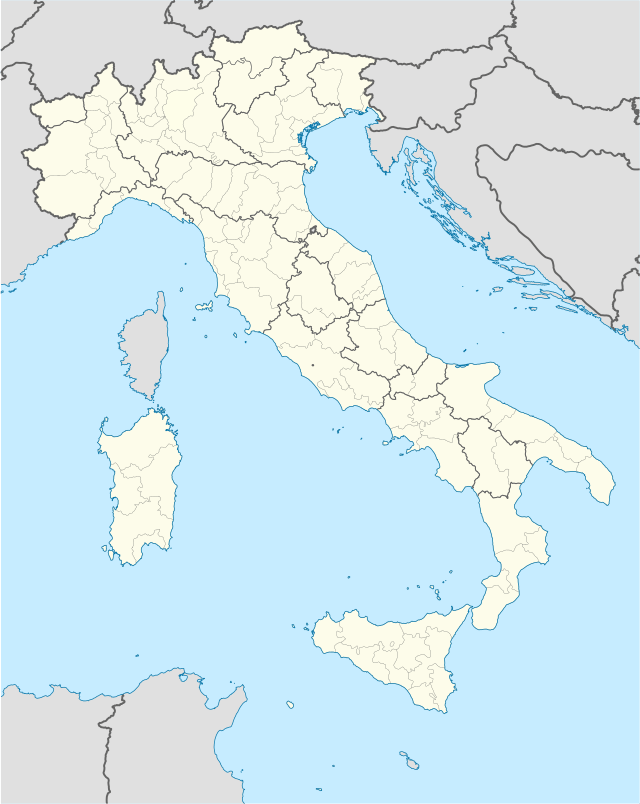

Location of Bari

| |

Bari Location of Bari in Italy  Bari Bari (Apulia) | |

| Coordinates: 41°07′31″N 16°52′0″E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | |

| Metropolitan city | Bari (BA) |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Antonio Decaro (PD) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 117 km2 (45 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 5 m (16 ft) |

| Population (31 December 2015)[2] | |

| • Total | 326,799 |

| • Density | 2,800/km2 (7,200/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Barese |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 70121-70132 |

| Dialing code | 080 |

| ISTAT code | 072006 |

| Patron saint | Saint Nicholas |

| Saint day | 8 May |

| Website | Official website |

Bari is made up of four different urban sections. To the north is the closely built old town on the peninsula between two modern harbours, with the Basilica of Saint Nicholas, the Cathedral of San Sabino (1035–1171) and the Hohenstaufen Castle built for Frederick II, which is now also a major nightlife district. To the south is the Murat quarter (erected by Joachim Murat), the modern heart of the city, which is laid out on a rectangular grid-plan with a promenade on the sea and the major shopping district (the via Sparano and via Argiro).

Modern residential zones surrounding the centre of Bari were built during the 1960s and 1970s replacing the old suburbs that had developed along roads splaying outwards from gates in the city walls. In addition, the outer suburbs developed rapidly during the 1990s. The city has a redeveloped airport, Karol Wojtyła Airport, with connections to several European cities.

History

Ancient

The city was probably founded by the Peucetii. The city had strong Greek influences[3] and once it passed under Roman rule in the 3rd century BC, it developed strategic significance as the point of junction between the coast road and the Via Traiana and as a port for eastward trade; a branch road to Tarentum led from Barium. Its harbour, mentioned as early as 181 BC, was probably the principal one of the districts in ancient times, as it is at present, and was the centre of a fishery.[4] The first historical bishop of Bari was Gervasius who was noted at the Council of Sardica in 347. The bishops were dependent on the Patriarch of Constantinople until the 10th century.

Middle Ages

After the devastations of the Gothic Wars, under Longobard rule a set of written regulations was established, the Consuetudines Barenses, which influenced similar written constitutions in other southern cities. Until the arrival of the Normans, Bari continued to be governed by the Longobards and Byzantines, with only occasional interruption.

Throughout this period, and indeed throughout the Middle Ages, Bari served as one of the major slave depots of the Mediterranean, providing a central location for the trade in Slavic slaves. The slaves were mostly captured by Venice from Dalmatia, the Holy Roman Empire from what is now Prussia and Poland, and the Byzantines from elsewhere in the Balkans, and were generally destined for other parts of the Byzantine Empire and (most frequently) the Muslim states surrounding the Mediterranean: the Abbasid Caliphate, the Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba, the Emirate of Sicily, and the Fatimid Caliphate (which relied on Slavs purchased at the Bari market for its legions of Sakalaba Mamluks).[5]

For 20 years, Bari was the centre of the Emirate of Bari; the city was captured by its first emirs Kalfun in 847, who had been part of the mercenary garrison installed there by Radelchis I of Benevento.[6] The city was conquered and the Emirate extinguished in 871, due to the efforts of Emperor Louis II and a Byzantine fleet.[7] Chris Wickham states Louis spent five years campaigning to reduce then occupy Bari, "and then only to a Byzantine/Slav naval blockade"; "Louis took the credit" for the success, adding "at least in Frankish eyes", then concludes by noting that by remaining in southern Italy long after this success, he "achieved the near-impossible: an alliance against him of the Beneventans, Salernitans, Neapolitans and Spoletans; later sources include Sawadān as well."[6] In 885, Bari became the residence of the local Byzantine catapan, or governor. The failed revolt (1009–1011) of the Lombard nobles Melus of Bari and his brother-in-law Dattus, against the Byzantine governorate, though it was firmly repressed at the Battle of Cannae (1018), offered their Norman adventurer allies a first foothold in the region. In 1025, under the Archbishop Byzantius, Bari became attached to the see of Rome and was granted "provincial" status.

In 1071, Bari was captured by Robert Guiscard, following a three-year siege. Maio of Bari (died 1160), a Lombard merchant's son, was the third of the great admirals of Norman Sicily. The Basilica di San Nicola was founded in 1087 to receive the relics of this saint, which were surreptitiously brought from Myra in Lycia, in Byzantine territory. The saint began his development from Saint Nicholas of Myra into Saint Nicholas of Bari and began to attract pilgrims, whose encouragement and care became central to the economy of Bari. In 1095 Peter the Hermit preached the first crusade there.[4] In October 1098, Urban II, who had consecrated the Basilica in 1089, convened the Council of Bari, one of a series of synods convoked with the intention of reconciling the Greeks and Latins on the question of the filioque clause in the Creed, which Anselm ably defended, seated at the pope's side. The Greeks were not brought over to the Latin way of thinking, and the Great Schism was inevitable.

A civil war broke out in Bari in 1117 with the murder of the archbishop, Riso. Control of Bari was seized by Grimoald Alferanites, a native Lombard, and he was elected lord in opposition to the Normans. By 1123, he had increased ties with Byzantium and Venice and taken the title gratia Dei et beati Nikolai barensis princeps. Grimoald increased the cult of St Nicholas in his city. He later did homage to Roger II of Sicily, but rebelled and was defeated in 1132.

Bari was occupied by Manuel I Komnenos between 1155 and 1158. In 1246, Bari was sacked and razed to the ground; Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Sicily, repaired the fortress of Baris but it was subsequently destroyed several times. Bari recovered each time.

Early modern period

Isabella d’Aragona, princess of Naples and widow of the Duke Gian Galeazzo Sforza of Milan, enlarged the castle, which she made her residence, 1499–1524. After the death of Queen Bona Sforza, of Poland, Bari came to be included in the Kingdom of Naples and its history contracted to a local one, as malaria became endemic in the region. Bari was awakened from its provincial somnolence by Napoleon's brother-in-law Joachim Murat. As Napoleonic King of Naples, Murat ordered the building in 1808 of a new section of the city, laid out on a rationalist grid plan, which bears his name today as the Murattiano. Under this stimulus, Bari developed into the most important port city of the region. The legacy of Mussolini can be seen in the imposing architecture along the seafront.

World War II

On 11 September 1943, in connection with the Armistice of Cassibile, Bari was taken without resistance by the British 1st Airborne Division, then during October and November 1943, New Zealand troops from the 2nd New Zealand Division assembled in Bari.

The Balkan Air Force supporting the Yugoslav partisans was based at Bari.

The 1943 chemical warfare disaster

Through a tragic coincidence intended by neither of the opposing sides in World War II, Bari gained the unwelcome distinction of being the only European city to experience chemical warfare in the course of that war.

On the night of 2 December 1943, 105 German Junkers Ju 88 bombers attacked the port of Bari, which was a key supply centre for Allied forces fighting their way up the Italian Peninsula. Over 20 Allied ships were sunk in the overcrowded harbour, including the U.S. Liberty ship John Harvey, which was carrying mustard gas; mustard gas was also reported to have been stacked on the quayside awaiting transport (the chemical agent was intended for retaliation if German forces had initiated chemical warfare.) The presence of the gas was highly classified and the U.S. had not informed the British military authorities in the city of its existence. This increased the number of fatalities, since British physicians—who had no idea that they were dealing with the effects of mustard gas—prescribed treatment proper for those suffering from exposure and immersion, which proved fatal in many cases. Because rescuers were unaware they were dealing with gas casualties, many additional casualties were caused among the rescuers, through contact with the contaminated skin and clothing of those more directly exposed to the gas.

Following the attack, the harbor was closed for operations for three weeks and it did not return to full capacity until February 1944.

A member of U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower's medical staff, Stewart F. Alexander, was dispatched to Bari following the raid. Alexander had trained at the Army's Edgewood Arsenal in New Jersey, and was familiar with some of the effects of mustard gas. Although he was not informed of the cargo carried by the John Harvey, and most victims suffered atypical symptoms caused by exposure to mustard diluted in water and oil (as opposed to airborne), Alexander rapidly concluded that mustard gas was present. Although he could not get any acknowledgement of this from the chain of command, Alexander convinced medical staffs to treat patients for mustard exposure and saved many lives as a result. He also preserved many tissue samples from autopsied victims at Bari. After World War II, these samples would result in the development of an early form of chemotherapy based on mustard, Mustine.[8]

On the orders of Allied leaders Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and Eisenhower, records were destroyed and the whole affair was kept secret for many years after the war. The U.S. records of the attack were declassified in 1959, but the episode remained obscure until 1967, when writer Glenn B. Infield exposed the story in his book Disaster at Bari.[8] Additionally, there is considerable dispute as to the exact number of fatalities. In one account: "[S]ixty-nine deaths were attributed in whole or in part to the mustard gas, most of them American merchant seamen".[9] Others put the count as high as "more than one thousand Allied servicemen and more than one thousand Italian civilians".[10]

Part of the confusion and controversy derives from the fact that the German attack, which became nicknamed "The Little Pearl Harbor" after the Japanese air attack on the American naval base in Hawaii, was highly destructive in itself, apart from the effects of the gas. Attribution of the causes of death to the gas, as distinct from the direct effects of the German attack, has proved far from easy.

The affair is the subject of two books: Disaster at Bari, by Glenn B. Infield, and Nightmare in Bari: The World War II Liberty Ship Poison Gas Disaster and Coverup, by Gerald Reminick.

In 1988 through the efforts of Nick T. Spark, U.S. Senators Dennis DeConcini and Bill Bradley, Dr. Stewart Alexander received recognition from the Surgeon General of the United States Army for his actions during the Bari disaster.[11]

Charles Henderson explosion

The port of Bari was again struck by disaster on 9 April 1945 when the Liberty ship Charles Henderson exploded in the harbour while offloading 2000 tons of aerial bombs (half of that amount had been offloaded when the explosion occurred). Three hundred and sixty people were killed and 1730 were wounded. The harbour was again rendered nonoperational, this time for a month.

9 April 1945 – View from the barracks. Photo by WOJG Hubert Platt Henderson who was stationed at Bari as the Director of the 773rd Band

9 April 1945 – View from the barracks. Photo by WOJG Hubert Platt Henderson who was stationed at Bari as the Director of the 773rd Band 9 April 1945 – Photo by WOJG Hubert Platt Henderson who was stationed at Bari as the Director of the 773rd Band

9 April 1945 – Photo by WOJG Hubert Platt Henderson who was stationed at Bari as the Director of the 773rd Band 9 April 1945 – Photo by WOJG Hubert Platt Henderson who was stationed at Bari as the Director of the 773rd Band

9 April 1945 – Photo by WOJG Hubert Platt Henderson who was stationed at Bari as the Director of the 773rd Band

Geography

Bari is the largest urban and metro area on the Adriatic. It is located in Southern Italy, at a more northerly latitude than Naples, further south than Rome.

Climate

Bari has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csa) with mild winters and hot, dry summers.

| Climate data for Bari Karol Wojtyła Airport | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 24.0 (75.2) |

24.0 (75.2) |

27.2 (81.0) |

32.6 (90.7) |

39.1 (102.4) |

41.4 (106.5) |

43.3 (109.9) |

44.8 (112.6) |

39.0 (102.2) |

35.2 (95.4) |

26.8 (80.2) |

23.0 (73.4) |

44.8 (112.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 12.6 (54.7) |

12.9 (55.2) |

15.0 (59.0) |

18.0 (64.4) |

22.8 (73.0) |

26.8 (80.2) |

29.2 (84.6) |

29.2 (84.6) |

25.9 (78.6) |

21.5 (70.7) |

16.8 (62.2) |

13.9 (57.0) |

20.4 (68.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 8.8 (47.8) |

8.9 (48.0) |

10.7 (51.3) |

13.3 (55.9) |

17.8 (64.0) |

21.8 (71.2) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.3 (75.7) |

21.1 (70.0) |

17.1 (62.8) |

12.7 (54.9) |

10.1 (50.2) |

15.9 (60.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 4.9 (40.8) |

4.8 (40.6) |

6.3 (43.3) |

8.6 (47.5) |

12.9 (55.2) |

16.7 (62.1) |

19.3 (66.7) |

19.4 (66.9) |

16.3 (61.3) |

12.6 (54.7) |

8.6 (47.5) |

6.2 (43.2) |

11.4 (52.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −5.9 (21.4) |

−3 (27) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

1.1 (34.0) |

5.3 (41.5) |

7.8 (46.0) |

12.8 (55.0) |

12.8 (55.0) |

8.4 (47.1) |

1.0 (33.8) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 53.7 (2.11) |

64.2 (2.53) |

42.0 (1.65) |

40.5 (1.59) |

34.9 (1.37) |

23.3 (0.92) |

25.4 (1.00) |

30.4 (1.20) |

59.7 (2.35) |

61.5 (2.42) |

72.7 (2.86) |

54.3 (2.14) |

562.6 (22.14) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 6.7 | 7.7 | 6.8 | 6.2 | 5.2 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 3.5 | 5.0 | 6.3 | 7.7 | 7.1 | 68.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 77 | 74 | 72 | 68 | 68 | 65 | 64 | 65 | 68 | 72 | 76 | 78 | 71 |

| Source 1: Servizio Meteorologico (1971–2000 data)[12] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Relative humidity: Servizio Meteorologico (1961–1990 data)[13] | |||||||||||||

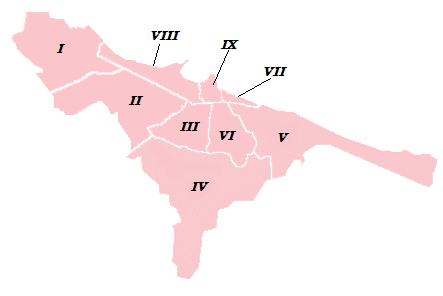

Quarters

Quarters of Bari | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

Shown above are the nine governmental community boards (Municipalities) of Bari: these are further divided into twenty neighbourhoods or "quartiere" as they are known.[14]

Architectural landmarks

.jpg)

- Teatro Margherita.

- Teatro Piccinni.

- Orto Botanico dell'Università di Bari, a botanical garden.

- Santa Chiara, once church of the Teutonic Knights (as Santa maria degli Alemanni) and now houses a museum. It was restored in 1539.

- The Acquedotto Pugliese

- The medieval church of San Marco dei Veneziani, with a rose window in the façade.

- Conservatory of Bari

- San Giorgio degli Armeni.

- Santa Teresa dei Maschi, the main Baroque church in the city (1690–1696).

- Pane e Pomodoro Beach is the main beach within reach of the city. Its reputation has for several years suffered from the apparent presence of asbestos from nearby industrial plants.

- Bari features two sea harbours: the Old Port and the New Port, constructed in 1850.

Basilica of Saint Nicholas

The Basilica di San Nicola (Saint Nicholas) was founded in 1087 to receive the relics of this saint, which were brought from Myra in Lycia, and now lie beneath the altar in the crypt, where are buried the Topins, which are a legacy of old thieves converted to good faith. The church is one of the four Palatine churches of Apulia (the others being the cathedrals of Acquaviva delle Fonti and Altamura, and the church of Monte Sant'Angelo sul Gargano).[4]

Bari Cathedral

Bari Cathedral, dedicated to Saint Sabinus of Canosa (San Sabino), was begun in Byzantine style in 1034, but was destroyed in the sack of the city of 1156. A new building was thus built between 1170 and 1178, partially inspired by that of San Nicola. Of the original edifice, only traces of the pavement are today visible in the transept.

An example of Apulian Romanesque architecture, the church has a simple Romanesque façade with three portals; in the upper part is a rose window decorated with monstruous and fantasy figures. The interior has a nave and two aisles, divided by sixteen columns with arcades. The crypt houses the relics of Saint Sabinus and the icon of the Madonna Odigitria.

The interior and the façade were redecorated in Baroque style during the 18th century, but these additions were removed in a 1950s restoration.

Petruzzelli Theatre

The Petruzzelli Theatre, founded in 1903, hosted different forms of live entertainment, or nineteenth century “Politeama”. The theatre was all but destroyed in a fire on October 27, 1991. It was reopened in October 2009, after 18 years.

Swabian Castle

The Norman-Hohenstaufen Castle, widely known as the Castello Svevo (Swabian Castle), was built by Roger II of Sicily around 1131. Destroyed in 1156, it was rebuilt by Frederick II of Hohenstaufen. The castle now serves as a gallery for a variety of temporary exhibitions in the city.

Pinacoteca Provinciale di Bari

The Pinacoteca Provinciale di Bari (Provincial Picture Gallery of Bari) is the most important art gallery in Apulia. It was first established in 1928 and contains many paintings from the 15th century up to the days of contemporary art.

The Russian Church

The Russian Church of Saint Nicholas, in the Carrassi district of Bari, was built in the early 20th century to welcome Russian pilgrims who came to the city to visit the church of Saint Nicholas in the old city where the relics of the saint remain.

The city council and Italian national government were recently involved in a trade-off with the Putin government in Moscow, exchanging the piece of land on which the church stands, for, albeit indirectly, a military barracks near Bari's central railway station.

Barivecchia

Barivecchia, or Old Bari, is a sprawl of streets and passageways making up the section of the city to the north of the modern Murat area. Barivecchia was until fairly recently considered a no-go area by many of Bari's residents due to the high levels of petty crime. A large-scale redevelopment plan began with a new sewerage system, followed by the development of the two main squares, Piazza Mercantile and Piazza Ferrarese.

Demographics

As of 2015, there were 326,344 people residing in Bari (about 1.6 million live in the greater Bari area), located in the province of Bari, Puglia, of whom 47.9% were male and 52.1% were female.[15] As of 2007, minors (children ages 18 and younger) totaled 17.90 percent of the population compared to pensioners who number 19.08 percent. This compares with the Italian average of 18.06 percent (minors) and 19.94 percent (pensioners). The average age of Bari residents is 42 compared to the Italian average of 42. In the five years between 2002 and 2007, the population of Bari grew by 2.69 percent, while Italy as a whole grew by 3.56 percent.[16] The current birth rate of Bari is 8.67 births per 1,000 inhabitants compared to the Italian average of 9.45 births.

As of 2015, 3.8% of the population was foreign residents.[17]

| Residents by Region | Residents by Nationality | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Migration

According to an urban migration study in Bari, return migration gain to urban areas is higher than migration loss from urban areas. People migrating from urban destinations tend to migrate to different places in comparison to people migrating from rural areas. These findings are based on the background and behavior of a sample of 211 return migrants to Bari, Italy. Bari is a port city, making it historically important because of its strong trade links with Greece, North Africa, and the eastern Mediterranean. Bari's economic structure is based on industry, commerce, services, and administration. Around two-thirds of the city's employment is in the tertiary sector with its port, commerce, and administrative functions. The highest percentage of Bari's working population is employed in services, with 45.6%. From 1958 to 1982, around 20% of migrants left Bari for other Italian communes, while around 17% or migrants came to Bari from other Italian communes. Under 2% of migrants left Bari to go abroad and came to the city from abroad.[18]

Culture

Fiera del Levante

The Fiera del Levante, held in September in the Fiera site on the west side of Bari city center, focuses on agriculture and industry, There is also a "Fair of Nations" which displays handcrafted and locally produced goods from all over the world.

Cuisine and gastronomy

Bari's cuisine is based on three typical agricultural products found within the surrounding region of Apulia, namely wheat, olive oil and wine. The local cuisine is also enriched by the wide variety of fruit and vegetables produced locally. Local flour is used in homemade bread and pasta production including, most notably, the famous orecchiette ear-shaped pasta, recchietelle or strascinate, chiancarelle (orecchiette of different sizes) and cavatelli.

Homemade dough is also used for baked calzoni stuffed with onions, anchovies, capers and olives; fried panzerotti with mozzarella, simple focaccia alla barese with tomatoes, little savoury taralli, friselle and sgagliozze, fried slices of polenta, all make up the Bari culinary repertoire.

Vegetable minestrone, chick peas, broad beans, chicory, celery and fennel are also often served as first courses or side dishes.

Meat dishes and the local Barese ragù often include lamb and pork.

Pasta al forno, a baked pasta dish, is very popular in Bari and was historically a Sunday dish, or a dish used at the start of Lent when all the rich ingredients such as eggs and pork had to be used for religious reasons. The recipe commonly consists of penne or similar tubular pasta shapes, a tomato sauce, small beef and pork meatballs and halved hard-boiled eggs. The pasta is then topped with mozzarella or similar cheese and then baked in the oven to make the dish have its trademark crispy texture.

Fresh fish and seafood are often eaten raw. Octopus, sea urchins and mussels feature heavily. Perhaps Bari's most famous dish is the oven-baked patate, riso e cozze (potatoes with rice and mussels).

Bari and the whole Apulian region have a range of wines, including Primitivo, Castel del Monte, and Muscat, notably Moscato di Trani.

Language

The dialect of Bari belongs to the upper-southern Italo-Romance family, and currently coexists with Italian; generally these are used in different contexts.

Notable people

- Licia Albanese

- Giovanni Alemanno

- Emanuele Arciuli

- Argyrus (catepan of Italy)

- Francesco Attolico

- Lino Banfi

- Pope Benedict XIII

- Gioia Bruno

- Gianrico Carofiglio

- Antonio Cassano

- Riccardo Cucciolla

- Niccolò dell'Arca

- Franco Giordano

- Alfredo Giovine

- Ivan Iusco

- Gaetano Latilla

- Guido Marzulli

- Antonio Matarrese

- Domenico Modugno

- Aldo Moro

- Pomponio Nenna

- Mario Nuzzolese

- Joe Orlando

- Anna Oxa

- Pino Pascali

- Nico Perrone

- Niccolò Piccinni

- Victor Posa

- Rocco Rodio

- Sergio Rubini

- Gaetano Salvemini

- Bona Sforza

- Cesare Stea

- Pope Urban VI

- Nichi Vendola

- Checco Zalone

Sport

Local football club S.S.C. Bari, currently competing in Serie C (as of the 2019–2020 season), plays in the Stadio San Nicola, an architecturally innovative 58,000-seater stadium purpose-built for the 1990 FIFA World Cup. The stadium also hosted the 1991 European Cup Final.

Economy and infrastructure

Transport

Bari has its own airport, Bari Karol Wojtyła Airport, which is located 8 km (5.0 mi) northwest of the centre of Bari. It is connected to the centre by train services from Bari Aeroporto railway station.

Bari Central Station lies on the Adriatic railway and has connection to cities such as Rome, Milan, Bologna, Turin and Venice. Another mainline is connection southwards by the Bari-Taranto railway. Regional services also operate to Foggia, Barletta, Brindisi, Lecce, Taranto and other towns and villages in the Apulia region.

Bari has an old fishery port (Porto Vecchio) and a so-called new port in the north, as well as some marinas. The Port of Bari is an important cargo transport hub to S.E.Europe. Various passenger transport lines include some seasonal ferry lines to Albania, Montenegro or Dubrovnik. Bari-Igoumenitsa is a popular ferry line to Greece, some cruise ships anchor in Bari too.

Public transportation statistics

The average amount of time people spend commuting with public transit in Bari, for example to and from work, on a weekday is 57 minutes. 11% of public transit riders ride for more than 2 hours every day. The average amount of time people wait at a stop or station for public transit is 18 minutes, while 40% of riders wait for over 20 minutes on average every day. The average distance people usually ride in a single trip with public transit is 4.2 km (2.6 mi), while 2% travel for over 12 km (7.5 mi) in a single direction.[19]

Twin towns — sister cities

Bari is twinned with:[20]

In popular culture

The Guido Guerrieri novels by Gianrico Carofiglio are set in Bari, where Guerrieri is a criminal lawyer, and include many descriptions of the town.

Bari is one of the primary settings of the detective novel The Black Mountain by Rex Stout. It is the characters' point of embarkation to Communist Yugoslavia.

In the 1995 film The Bridges of Madison County, Italian housewife Francesca Johnson (Meryl Streep), is mentioned as being from Bari and growing up in Naples.

Gallery

See also

- Accademia Apulia

- Antivari (means "opposite Bari")

- Bari Light, the Punta San Cataldo di Bari Lighthouse

- Durres

- Polytechnic University of Bari

- Province of Bari

- University of Bari

References

- "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Istat. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- 'City' population (i.e. that of the comune or municipality) from Monthly demographic balance: January–April 2009, ISTAT.

- https://www.britannica.com/place/Bari-Italy

-

- The Cartoon History of the Universe III – From the Rise of Arabia to the Renaissance (Volumes 14–19). Doubleday. 2002. ISBN 0-393-32403-6.

- Chris Wickham (1981). Early Medieval Italy: Central Power and Local Society 400–1000. Totowa: Barnes and Noble. pp. 62, 154. ISBN 978-0-389-20217-2.

- Hilmar C. Krueger (1955). "The Italian Cities and the Arabs before 1095". In Kenneth Meyer Setton; Marshall W. Baldwin (eds.). A History of the Crusades: The First Hundred Years. Vol. I. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 48.

- Glenn Infield (1976). Disaster at Bari. ISBN 978-0-450-02659-1..

- "US Naval Historical Center report". Archived from the original on January 12, 2008.

- Amazon book summary of Gerald Reminick (2001). Nightmare in Bari: The World War II Liberty Ship Poison Gas Disaster and Coverup. Glencannon Press. ISBN 978-1-889-90121-3.

- "Tucson Senior Helps Retired Doctor Receive Military Honor". Mohave Daily Miner. Kingman, Arizona. May 20, 1988. p. B8 – via Google News.

- "Bari/Palese (BA) 44 m. s.l.m. (a.s.l.)" (PDF). Servizio Meteorologico. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- "Stazione 270 Bari, medie mensili periodo 61 – 90". Servizio Meteorologico. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- "Quartieri". Palapa.it. 8 January 2008. Archived from the original on 13 August 2013. Retrieved 31 October 2008.

- "Popolazione Bari 2001-2015". Comuni-Italiani.it (in Italian). Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- "Statistiche demografiche ISTAT". Demo.istat.it. Archived from the original on 26 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- "Cittadini Stranieri - Bari" [Foreigners - Bari]. Comuni-Italiani.it (in Italian). Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- King, Russel; Strachan, Alan; Mortimer, Jill (June 1985). "The Urban Dimension of European Return Migration: The Case of Bari, Southern Italy". Urban Studies. 22 (3): 219–235. doi:10.1080/00420988520080361. JSTOR 43192080.

- "Facts and usage statistics about public transit in Bari, Italy". moovit insights. Moovit Public Transit Index. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- "I sedici gemellaggi di Bari". quotidianodibari.it (in Italian). Quotidiano di Bari. 2017-07-11. Retrieved 2019-12-13.

Further reading

- Glenn B. Infield. 1973. Disaster at Bari. Ace Books. New York, N.Y.

- Vito Antonio Melchiorre. 2001. Note storiche su Bari.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bari. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Bari. |

- Top 7 Things to Do in Bari, Italy

- City of Bari

- Province of Bari

- Region of Apulia

- Worldfacts: "Bari, Italy"

- Catholic Encyclopedia; "Bari"

_2017.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)