Milton Damerel

Milton Damerel is a village, parish and former manor in north Devon, England. Situated in the political division of Torridge, on the river Waldon, it covers 7 square miles (18 km2). It contains many tiny hamlets including Whitebeare, Strawberry Bank, East Wonford and West Wonford. The parish has a population of about 450. The village is situated about 5 miles (8.0 km) from Holsworthy, 13.081 miles (21.052 km) from Bideford and 22.642 miles (36.439 km) from Barnstaple. The A388 is the main road through the parish.

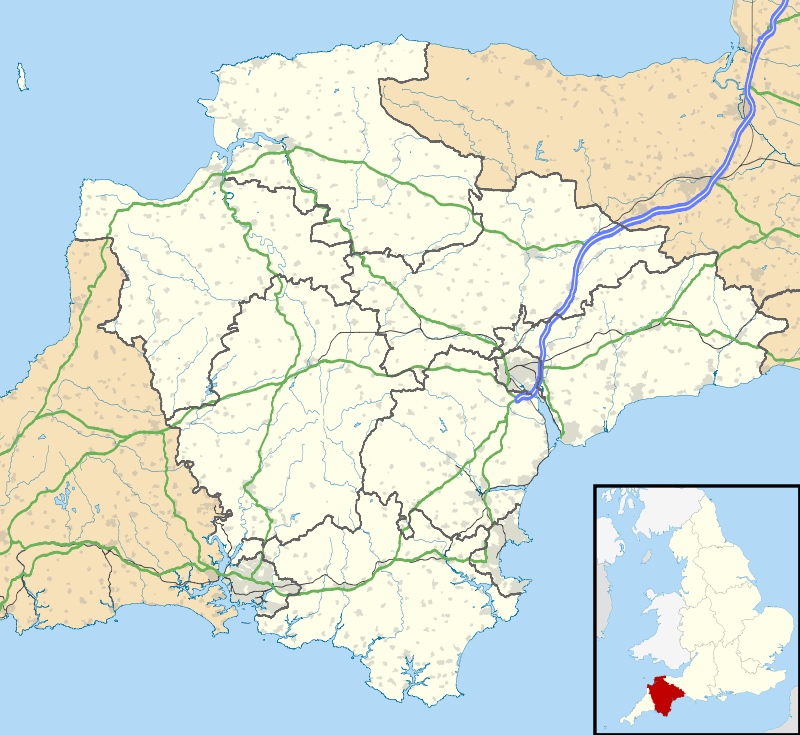

| Milton Damerel | |

|---|---|

Milton Damerel Location within Devon | |

| Population | 450 |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | HOLSWORTHY |

| Postcode district | EX22 |

| Dialling code | 01409 |

| Police | Devon and Cornwall |

| Fire | Devon and Somerset |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

History

Milton Damerel's settlement dates back to Saxon times. Pre-Norman settlements included:

- Gidcott (Latinized to Giddescotta), the cott or semi-independent estate of an Anglo-Saxon man named Gidde.

- Middleton (Mideltona) i.e. Middle Town, which became 'Milton'.

- Wonford (Wonforda) i.e. West Wonford. The Saxon name signified "a ford suitable for heavy wagons".

Following the Norman Conquest of 1066, William the Conqueror granted West Wonford, with twenty-eight other manors in Devon, to Ruald Adobed, but it later escheated to the Crown. However Milton, Gidcott and thirteen other manors in Devon he granted to Robert d'Aumale (fl. 1086) (Latinised to de Albemarle), whose lands are listed in 17 entries in the Domesday Book of 1086.[1] He was lord of Aumale in Normandy, now in the département of Seine-Maritime, France.[2] The majority of his holdings later formed part of the very large feudal barony of Plympton.[3] His descendants appear to have become known as Damerel, Damarrell, etc.

In the Book of Fees "John de Albemarle" is listed as holding Middelton, part of the feudal barony of Plympton, from Isabella de Forz, widow of William de Forz, 4th Earl of Albemarle and suo jure Countess of Devon,[4] whose heir was the Courtenay family.

The 6th Earl[5] was succeeded by his son, Baldwin de Redvers, 7th Earl of Devon (d.1262),[6] who died without progeny. His sister, Isabella de Forz, widow of William de Forz, 4th Earl of Albemarle, became Countess of Devon suo jure.[7] Her children predeceased her and she had no grandchildren.

Her lands were inherited by her second cousin once removed, Hugh de Courtenay (1276–1340),[8] feudal baron of Okehampton, the great-grandson of Mary de Redvers and Robert de Courtenay (d.1242) of Okehampton. He was summoned by writ to Parliament in 1299 as Hugo de Curtenay,[9] whereby he is held to have become Baron Courtenay.[10] However, forty-one years after the death of Isabel de Forz, letters patent were issued on 22 February 1335 declaring him Earl of Devon, and stating that he 'should assume such title and style as his ancestors, Earls of Devon, had wont to do', by which he was confirmed as Earl of Devon.[11]

The manor of Milton Damerel remained held from the honour of Plympton by the family of the Damerels until the time of King Edward II (1307-1327), when Hugh Courtenay (1303-1377), later 2nd Earl of Devon, of Tiverton Castle, "procured"[12] possession of it from Ralph Damerel. Courtenay retained the manor house and lordship of the manor, but granted the demesne lands of it to Sir Richard Stapledon (d.1326) of Annery, Monkleigh in North Devon.[13] These demesne lands passed with Annery to Sir Richard I Hankford,[14] heir by marriage to Stapledon, whose descendant was Sir William Hankford (d. 1422), KB, Lord Chief Justice of England. In 1538 the Courtenays lost the manor of Milton Damerel and their other possessions following the attainder and execution of Henry Courtenay, 1st Marquess of Exeter (c.1498-1538).[15]

In the 1870s, Richard Baker, tenant of the main farm, built a large house next to the church; in 1896 he got permission from Arthur Stanhope, 6th Earl Stanhope to enclose the village green.

The parish has a Grade II* listed Holy Trinity Parish Church that dates back to, in parts, the 13th century. The tower was destroyed by lighting in 1879 and for 20 years the church was in ruins but was re-opened in 1904 and the tower partly re-erected in 1892 and rebuilt in 1910 - 11. The church holds weekly services and other events in the old school room.[16]

Buildings and facilities

The parish has no schools, though the children in the parish normally go to schools in Bradworthy, Holsworthy, and North Devon College.

Milton Damerel has many small businesses that serve the local community. Although the parish doesn't have a post office, there are ones in Bradworthy, Holsworthy and a part-time one in Shebbear.[17]

The parish has a parish hall that is used for community events. It has a skittle alley attached, with skittle league matches taking place there during the winter months. The hall and skittle alley are both available for private hire.

There is a mobile library that visits the parish every two weeks. There is a permanent library in Holsworthy.

The 'Woodford Bridge Country Club' on the A388 is a former coaching inn, with a thatched roof. It is believed to be the 'Woodford Hall' where the diatomist Frederick Mills lived in the 1930s.[18]

Public transport

There is a bus service that operates 4 times a day, in each direction, along the A388 between Holsworthy and Bideford and then on to Barnstaple. On Saturday mornings a bus used to go to Launceston, Tavistock and Plymouth with a return service later in the day. This service however no longer is in operation, much to the dismay of local residents who relied on the service to go to Plymouth mainly for a Saturday shopping trip or to see friends.

Gallery

Chapel at Milton Damerel

Chapel at Milton Damerel Milton Damerel's church

Milton Damerel's church Cottages at Milton Damerel

Cottages at Milton Damerel

References

- Thorn, Caroline & Frank, (eds.) Domesday Book, (Morris, John, gen.ed.) Vol. 9, Devon, Parts 1 & 2, Phillimore Press, Chichester, 1985, part 2, Chapter 28

- Thorne & Thorne, part 2 (notes), chapter 28

- Thorn, Caroline & Frank, (eds.) Domesday Book, (Morris, John, gen.ed.) Vol. 9, Devon, Parts 1 & 2, Phillimore Press, Chichester, 1985, part 2 (notes), 28,1 "Milton Damerell"

- Thorn, Caroline & Frank, (eds.) Domesday Book, (Morris, John, gen.ed.) Vol. 9, Devon, Parts 1 & 2, Phillimore Press, Chichester, 1985, part 2 (notes), 28,1 "Milton Damerell"

- Cokayne 1916, pp. 318–19.

- Cokayne 1916, pp. 319–22.

- Cokayne 1916, pp. 322–3.

- Cokayne 1916, pp. 323–4

- Hugo nominative Latin form, Hugoni dative, i.e. writ to Hugoni...

- Cokayne 1916, p. 323; Richardson I 2011, p. 539.

- Cokayne 1916, p. 323.

- Pole, Sir William (d.1635), pp.364-5

- Pole, p.365

- Pole, p.365

- Pole, p.365

- British Listed Buildings Milton Damerel church

- Milton Damerel community website http://www.miltondamerel.com/about.htm

- David Walker: 'Notes on aspects of the life and work of Frederick William Mills (1868-1949), diatomist' http://www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/mag/artmay12/dw-fwmills.html

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Milton Damerel. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |