Huish, Devon

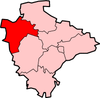

Huish (anciently Hiwis[1]) is a small village, civil parish and former manor in the Torridge district of Devon, England. The eastern boundary of the parish is formed by the River Torridge and the western by the Rivers Mere and Little Mere,[2] and it is surrounded, clockwise from the north, by the parishes of Merton, Dolton, Meeth and Petrockstowe.[3] In 2001 the population of the parish was 49, down from 76 in 1901.[2]

The village lies just off the A386 road, about five and a half miles north of Hatherleigh, and about seven miles south of Great Torrington. It was a member of the historic hundred of Shebbear and was in the deanery of Torrington.[4]

The majority of the parish consists of parkland belonging to Heanton Satchville, the seat of Baron Clinton;[2] the mansion-house is a few hundred yards to the north of the church.

Parish church

The church, dedicated to St James the Less, was heavily restored in 1873 by the 20th Baron Clinton to the designs of George Edmund Street, work described by Pevsner as "not of his best".[5] The 15th-century tower is the only part that remains unaltered.[6] The church contains a monument to John Cunningham Saunders, the noted eye surgeon who was born in the parish in 1773.[6]

Manor

Gotshelm

The manor is listed in the Domesday Book of 1086 as Hiwis, the 2nd of the 28 Devonshire holdings of Gotshelm,[7] one of the Devon Domesday Book tenants-in-chief of King William the Conqueror. He held it in demesne.[8] The tenant before the Norman Conquest of 1066 was an Anglo-Saxon named Alwy.[9] It is today believed to have been centred on the estate of Lovistone,[10] within the parish. Gotshelm was an Anglo-Norman magnate and was the brother of Walter de Claville (floruit 1086),[11] also a Devon Domesday Book tenant-in-chief, who as listed in the Domesday Book had 32 holdings in Devon from the king.[12] Before the end of the 13th century the Devonshire estates of both brothers formed part of the feudal barony of Gloucester.[13]

de Hiwis

In Kirkby's Quest, a survey of 1284–1285, the manor of Huish was recorded as being held by Richard de Hiwis,[14] whose family had, as was usual, taken their surname from their seat. According to the Book of Fees (pre-1302), the estate of Lovelleston (today Lovistone), within the parish, was however held by Robert Pollard,[15] directly from the feudal barony of Gloucester.[10] According to Sir William Pole (d.1635) the last in the male line of the de Hiwis family was William de Hiwis, who died without issue late in the reign of King Edward III, whose sister and heiress Emma de Hiwis married Sir Robert Tresilian[16] (d.1388), Chief Justice of the King's Bench, after whose execution she remarried to Sir John Coleshill.

Yeo

Tristram Risdon (d.1640) relates further that the land was subsequently purchased by Leonard Yeo who built a new house there. The principal seat of the Yeo family had been at nearby Heanton Satchville, Petrockstowe, which had passed by marriage to the Rolles, then by inheritance to the Trefusis family. His descendant, also Leonard Yeo, owned the manor in Risdon's time.[20] The manor remained in the Yeo family until it was sold by Edward Roe Yeo (died 1782), MP. Various 18th-century mural monuments to the Yeo family survive in the parish church.

Innes-Ker

John Dufty purchased the estate from Edward Roe Yeo (died 1782) who in 1782 sold it to the Scottish nobleman Sir James Norcliffe Innes (d.1823), later 5th Duke of Roxburghe, who built a new mansion house on the estate, which he called Innes House. He sold the manor to Richard Eales.

Trefusis

In about 1812 Richard Eales sold the manor to Robert Cotton St John Trefusis, 18th Baron Clinton,[4] a member of an ancient Cornish family. Clinton renamed the estate as Heanton Satchville, after his former family home at Heanton Satchville, Petrockstowe, across the valley to the west, which had burned down in 1795.[21] In the early 20th century, following his inheritance from Mark Rolle (d.1907) (born Trefusis, a younger son of the 19th Baron Clinton) of the vast former Rolle estates, Baron Clinton utilised the grander Bicton House, the former Rolle seat, as his main residence.[22] However this was vacated in the mid-20th century and the family moved back to Heanton Satchville, which today remains the seat of the Barons Clinton, now the Fane-Trefusis family, the largest landowners in Devon through the Clinton Devon Estates, the lands of which are principally situated near Bicton, in East Devon.

Historic estates

The parish of Huish includes the following historic estates:

- Lovistone (anciently Lovelleston), which according to the Book of Fees (pre-1302), was held by Robert Pollard,[23] directly from the feudal barony of Gloucester.[10] In the 18th century it was the seat of the Saunders family, most notably John Cunningham Saunders (1737–1783), Esquire, Senior,[24] whose 2nd son was John Cunningham Saunders (1773-1810), Junior, an English surgeon and oculist, best known for his pioneering work on the surgery of cataracts who in 1805 founded the Royal London Ophthalmic Hospital, now known as Moorfields Eye Hospital. Mural monuments to both men survive in the bell-tower of Huish Church. The will of an earlier John Cunningham Saunders "Gentleman of Great Torrington , Devon", near Huish, was proved on 14 April 1744.[25]

Notes

- Per research conducted by Sheila Yeo of the Yeo Society,[17] based on stained glass depictions of Yeo arms in churches of Petrockstowe (Yeo of Heanton Satchville) and Hatherleigh (Yeo of Hatherleigh) both in Devon. The ducks are described as of various breeds by different sources. Heraldic sources give contradictory tinctures: Argent, a chevron between three shovelers sable (Vivian),[18] and Argent, a chevron between three mallards azure (Pole).[19]

References

- Pole, Sir William (d.1635), Collections Towards a Description of the County of Devon, Sir John-William de la Pole (ed.), London, 1791, p.380

- Harris, Helen (2004). A Handbook of Devon Parishes. Tiverton: Halsgrove. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-84114-314-9.

- "Map of Devon Parishes" (PDF). Devon County Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- Lysons, Daniel; Lysons, Samuel (1822). Magna Britannia, Volume Six, containing Devonshire. London: Thomas Cadell. pp. 284–5. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1989) [1952]. Cherry, Bridget (ed.). The Buildings of England: Devon. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. p. 497. ISBN 978-0-14-071050-2.

- Hoskins, W. G. (1972). A New Survey of England: Devon (New ed.). London: Collins. p. 413. ISBN 978-0-7153-5577-0.

- Thorn, Caroline & Frank, (eds.) Domesday Book, (Morris, John, gen.ed.) Vol. 9, Devon, Parts 1 & 2, Phillimore Press, Chichester, 1985, Part 2 (Notes), Chapter 25:2

- Ipse Go(scelmus) ten(et) Hiwis ("Gotshelm holds Huish himself")

- Thorn, part 1, chap 25:2

- Thorn, part 2 (notes), chap 25:2

- Thorn, part 2 (notes), chap 24

- Thorn, part 1, chap 24, 1-32

- Thorn, part 2 (notes), chapters 24 & 25

- O. J. Reichel (1914). "The Hundred of Lifton in the time of Testa de Nevil, A.D. 1243". Report & Transactions of the Devonshire Association. XLVI: 211.

- The prominent Pollard family was later seated at Way, St Giles-in-the-Wood, see Lewis Pollard

- Pole, p.380

- Yeo, Sheila (2006). "Evidence of the correct Yeo Coat of Arms". The Yeo Family History and One Name Study. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- Vivian, p. 834

- Pole, Sir William (died 1635), Collections Towards a Description of the County of Devon, Sir John-William de la Pole (ed.), London, 1791, p. 510

- Risdon, Tristram (1811). Rees; et al. (eds.). The Chorographical Description or Survey of the County of Devon (updated ed.). Plymouth: Rees and Curtis. pp. 266–7.

- Lauder, Rosemary (2002). Devon Families. Tiverton: Halsgrove. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-84114-140-4.

- Lauder

- The prominent Pollard family was later seated at Way, St Giles-in-the-Wood, near Great Torrington; see Lewis Pollard

- As stated on monuments of John Cunningham Saunders I & II at Huish

- National Archives, Kew PROB 11/733/61

External links

- Listed Building text, Heanton Satchville

- Listed Buildings text, Church of St James the Less

- Clinton Devon Estates website