Doddiscombsleigh

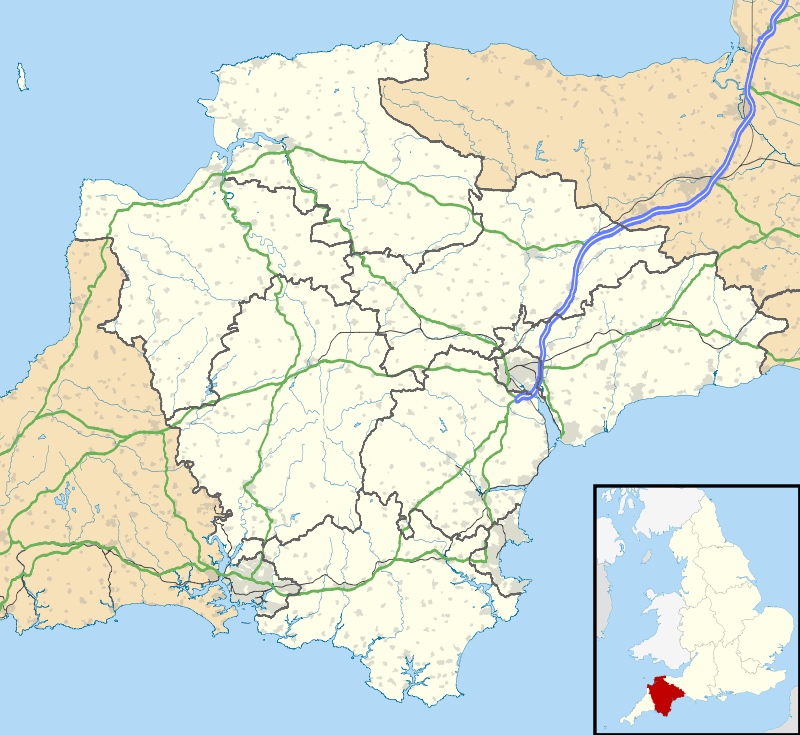

Doddiscombsleigh (anciently Doddescombe Leigh[1]) is a small settlement in Devon, England. It is 5 miles (8 km) southwest of the city of Exeter and one mile East of the River Teign and the Teign Valley.

| Doddiscombsleigh | |

|---|---|

St Michaels Church, Doddiscombsleigh | |

Doddiscombsleigh Location within Devon | |

| Area | 2.61 sq mi (6.8 km2) |

| OS grid reference | SX8586 |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | EXETER |

| Postcode district | EX6 |

| Dialling code | 01647 |

| Police | Devon and Cornwall |

| Fire | Devon and Somerset |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

Geography

Despite its proximity to the city, the village is difficult to find, as it is surrounded by twisting-narrow-lanes and deep valleys, tucked away in the shelter of the Haldon Hills. The village is accessed via minor roads which are predominately single track with passing places. The A38 passes within 3 miles (5 km) at Haldon Hill. The war memorial has the OS grid reference SX 855 865 and, for satnav users, the postcode is EX6 7PS.

The parish is 2,391 acres in size.[2]

Geologically, the village placed on the outer perimeter of the metamorphic aureole surrounding Dartmoor. There is a fault running along the valley in the region which became heavily mineralised with metalliferous ores. This made the area well known historically for its mining activities. In Doddiscombsleigh there were many manganese workings,[3] and Jasper could be found.[2]

Landmarks

Parish Church

The C of E parish church of St Michael is in the village and is a grade I listed building. St Michael’s contains the greatest collection of medieval stained glass to be found in situ anywhere in Devon, apart from that in the Great East Window of Exeter Cathedral. The panels in St Michael’s, which were installed c1480, were all produced in the 15th century by the same glazing workshop as some of the glass at Exeter Cathedral.[4]

These panels left Exeter over five hundred years ago - around the time of the Wars of the Roses - transported out of the city during the late Middle Ages on a cart and hauled up and down the precipitous Haldon Hill, before being installed in the church for which they were made. And they remain there today, rare survivals of perhaps the most fragile of medieval art forms.

The church was extensively restored and rebuilt by the architect Edward Ashworth in the late 1870s.[4]

Town Barton

Town Barton - which lies between the church of St Michael and The NoBody Inn is the historic Manor house; also known as the Capital Messuage or Mansion House of Doddiscombsleigh. The current building in a 17th-century grade II listed building.[5]

The first record of Town Barton was in the Domesday Book of 1086 when Doddiscombsleigh was known as Terra Godeboldi under the reign of one Godbold the Bowman. Town Barton was the Capital Barton (Manor House) for Godbold`s Domesday Estates.

This makes it one of the very rare instances of a property truly being specifically traceable to where a Doomsday owner dwelt. The manor of Doddiscombsleigh was also known as Legh-Peverel, but the name was dropped when the manor changed hands, with a Sir Ralph Doddescomb being recorded as living in the old mansion house in the reign of Henry III (1216-1272).

Town Barton was renowned for its twenty acres of apple orchards which produced "remarkably fine cider", no doubt supplying the local hostelries.

The NoBody Inn

The cottage that is now The NoBody Inn was listed as a "dwelling houses” or “messuage" in 1837, but, from the early 1600s at least, it was the village's unofficial Church House. Originally called Pophill Howse, details are sparse until 1752 when it was owned by Stephen Diggines "the church carpenter". The Inn has had a curious role in the parish. It did not formally become The New Inn until 1838, although it is believed to have been informally established in the late 18th century to provide "liquid refreshments" for the many men who worked in the mines of the hills at Ashton, Doddiscombsleigh and Christow, in their efforts to satisfy the huge demand for manganese for use in the potteries and for bleaching.[6]

The name of the pub came from 1952 when the landlord died, and the undertaker and the pallbearers failed to notice that there was no body in the coffin when it was buried in the village churchyard. The same day, the undertakers noticed that they still had the body. They telephoned the inn during the wake and the mourners were told of the mishap. The empty coffin was duly dug up and re-buried.[7]

An alternative explanation is that a landlord of the inn was in the habit of leaving his potman in charge of the inn when he went out on business. The potman was either shy or lazy, and when travellers came knocking at the inn door seeking refreshment would shout "There's nobody in!"

External links

![]()

References

- Pole, Sir William (d.1635), Collections Towards a Description of the County of Devon, Sir John-William de la Pole (ed.), London, 1791, p.256

- GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth, History of Doddiscombsleigh, in Teignbridge and Devon | Map and description, A Vision of Britain through Time

- Andrew Westcott (2003). "MANGANESE MINING In Doddiscombesleigh - A study of the remains of the old undocumented manganese workings around this village in South-West England". QSL.net.

- Historic England. "Church of St Michael (1333908)". National Heritage List for England.

- Historic England. "Town Barton (1097777)". National Heritage List for England.

- "History". www.nobodyinn.co.uk. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- Adam Edwards (16 October 2004). "Pint to pint: Nobody Inn". The Daily Telegraph.