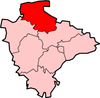

Barnstaple

Barnstaple (/ˈbɑːrnstəbəl/ (![]()

| Barnstaple | |

|---|---|

%2C_Clock_Tower_--_2013_--_0986.jpg) Barnstaple Clock Tower | |

Barnstaple Location within Devon | |

| Population | 24,033 |

| OS grid reference | SS5633 |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BARNSTAPLE |

| Postcode district | EX31, EX32 |

| Dialling code | 01271 |

| Police | Devon and Cornwall |

| Fire | Devon and Somerset |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

Toponymy

The old spelling Barnstable is now obsolete, but is retained by an American county and town. The name is first recorded in the 10th century and is believed to derive from the Old English bearde, meaning "battle-axe", and stapol, meaning "pillar", referring to a post or pillar set up to mark a religious or administrative meeting place. The belief that the name derives from staple meaning "market", indicating that there was a market here from the foundation of the settlement, is incorrect, because the use of staple in that sense is not recorded in England before 1423.[5]

Barnstaple was formerly referred to as "Barum", from a contraction of the Latin form of the name (ad Barnastapolitum) in Latin documents such as the episcopal registers of the Diocese of Exeter.[6] Barum was mentioned by Shakespeare, and the name was revived and popularised in Victorian times, when it was featured in several contemporary novels. The name Barum is retained in the names of a football team, brewery, several local businesses, and the numerous old milestones locally. The former Brannam Pottery works, which was sited in Litchdon Street, was known for its trademark "Barum" etched on the base of its products.

History

The earliest settlement in the area was probably at Pilton on the bank of the River Yeo, now a northern suburb of the present town. Pilton is recorded in the Burghal Hidage (c. 917) as a burh founded by Alfred the Great,[7] and it may have been the site of a Viking attack in 893,[8] but by the later 10th century Barnstaple had taken over its role of local defence. Barnstaple had its own mint before the Norman Conquest.[7]

The large feudal barony of Barnstaple had its caput at Barnstaple Castle. It was granted by William the Conqueror to Geoffrey de Montbray, who is recorded as its holder in Domesday Book. The barony escheated to the crown in 1095 after Montbray had rebelled against King William II. William re-granted the barony to Juhel de Totnes, formerly feudal baron of Totnes. In about 1107, Juhel, who had already founded Totnes Priory, founded Barnstaple Priory, of the Cluniac order, dedicated to St Mary Magdalene.[9] After Juhel's son died without children, the barony was split into two, passing through the de Braose and Tracy families, before being reunited under Henry de Tracy. It then passed through several other families, before ending up in the ownership of Margaret Beaufort (died 1509), mother of king Henry VII.

In the 1340s the merchants of the town claimed that the rights of a free borough had been granted to them by King Athelstan in a lost charter. Although this was challenged from time to time by subsequent lords of the manor, it still allowed the merchants an unusual degree of self-government.[10] The town's wealth in the Middle Ages was founded on its being a staple port licensed to export wool. It had an early merchant guild, known as the Guild of St. Nicholas. In the early 14th century it was the third richest town in Devon, behind Exeter and Plymouth, and it was the largest textile centre outside Exeter until about 1600.[11] Its wool trade was further aided by the town's port, from which in 1588 five ships were contributed to the force sent to fight the Spanish Armada. Barnstaple was one of the "privileged ports" of the Spanish Company,[12] (established 1577) whose armorials are visible on two of the mural monuments to 17th century merchants[lower-alpha 2] in St Peter's Church, and on the decorated plaster ceiling of the former "Golden Lion Inn",[14] 62 Boutport Street (now a restaurant next to the Royal and Fortescue Hotel).[lower-alpha 3] The developing trade with America in the 16th and 17th centuries greatly benefited the town. The wealthy merchants that this trade created built impressive town houses, some of which survive behind more recent frontages — they include No. 62 Boutport Street, said to have one of the best plaster ceilings in Devon.[15] The merchants also built several almshouses including Penrose's, and ensured their legacy by dedicating elaborate monuments to their families inside the church.[15]

By the 18th century, Barnstaple had ceased to be a woollen manufacturing town, which was replaced by Irish wool and yarn, for which it was the main landing place; the raw materials were carried by land to the new clothmaking towns in mid- and east Devon, such as Tiverton and Honiton.[11] However, the harbour was gradually silting up — as early as c. 1630 Tristram Risdon reported that "it hardly beareth small vessels"—and Bideford, which is lower down the estuary and benefits from the scouring action of the fast flowing River Torridge, gradually took over the foreign trade.[11]

Although for a time between 1680 and 1730, Barnstaple's trade was surpassed by Bideford's, it retained its economic importance until the early 20th century,[11] when it was manufacturing lace, gloves, sail-cloth and fishing-nets, it had extensive potteries, tanneries, sawmills and foundries, and shipbuilding was also carried on.[16] The Bear Street drill hall was completed in the early 19th century.[17]

Barnstaple was one of the boroughs reformed by the Municipal Reform Act 1835. Between the 1930s and the 1950s the town swallowed the villages of Pilton, Newport, and Roundswell through ribbon development.

Government

Internal government

The historic Borough of Barnstaple was long governed by the Mayor of Barnstaple and the Corporation. The seat of government was the Barnstaple Guildhall.[18] The mayor served a term of one year and was elected annually on the Feast of the Assumption of the Virgin (15 August) by a jury of twelve.[19] However Barnstaple was a mesne borough[19] and was not held by the Mayor and Corporation in chief from the king but from the feudal baron of Barnstaple, later known as the lord of the "Castle Manor" or "Castle Court". The Corporation tried on several occasions to claim the status of a "free borough" which answered directly to the monarch and to divest itself of this overlordship, but without success. The mayor was not recognised as such by the monarch, but merely as the bailiff of the feudal baron.[19] The powers of the borough were highly restricted, as was determined by an inquisition ad quod damnum during the reign of King Edward III, which from an inspection of evidence found that members of the corporation elected their mayor only by permission of the lord, legal pleas were held in a court at which the lord's steward, not the mayor, presided, that the borough was taxed by the county assessors, and that the lord held the various assizes which the burgesses claimed.[19] Indeed, the purported ancient royal charter supposedly held by the corporation which granted it borough status was suspected to be a forgery.[19]

Since 1974 Barnstaple has been a civil parish governed by a town council.[20]

Parliamentary representation

From 1295 the Borough of Barnstaple was represented in the House of Commons by two members of parliament until 1885, when its representation was reduced to one member. The constituency was abolished for the 1950 general election and was consolidated into the large modern constituency of North Devon, which was held by Nick Harvey, MP, of the Liberal Democrats from 1992 until 2015. In the 2015 United Kingdom general election, Peter Heaton-Jones of the Conservative Party was elected and re-elected again in 2017 with an increased vote share of 45.8 per cent.

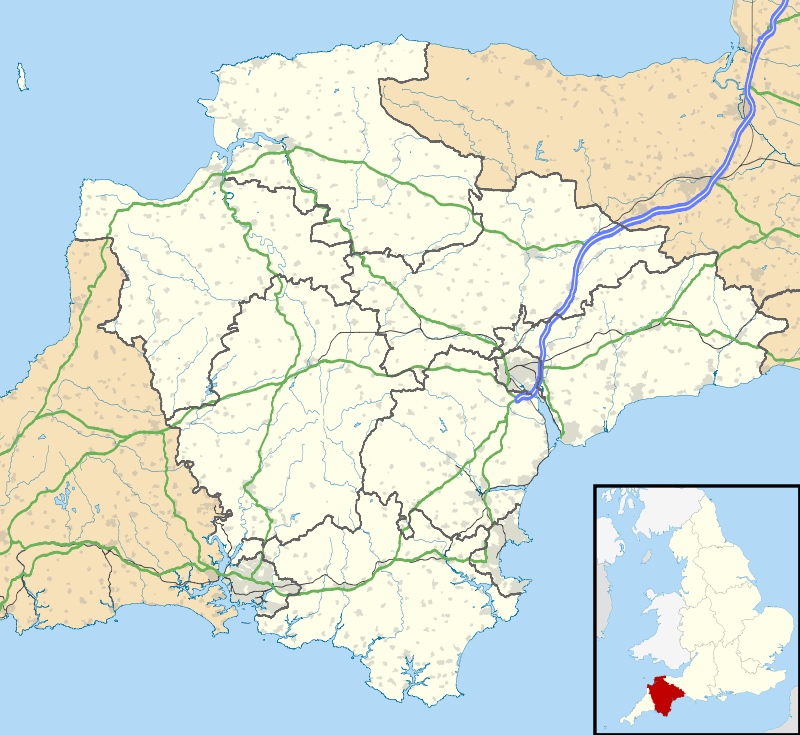

Geography

Barnstaple is the main town of North Devon and claims to be the oldest borough in the United Kingdom. It lies 68 miles (109 km) west-south-west of Bristol, 50 miles (80 km) north of Plymouth and 34 miles (55 km) north-west of the county town and city of Exeter. It was founded at the lowest crossing point of the River Taw, where its estuary starts to widen, about 7 miles (11 km) inland from Barnstaple Bay (or Bideford Bay) in the Bristol Channel.[7] On the north side of the town, the River Taw is joined by the River Yeo, which rises on Berry Down, near Combe Martin.

The greater part of the town lies on the eastern bank of the estuary, connected to the western side by the ancient Barnstaple Long Bridge which has 16 arches.[7] The early medieval layout of the town is still apparent from the street plan and street names, with Boutport Street ("About the Port") following the curved line of the ditch outside the town walls.[15] The area of medieval shipbuilding and repair is still called The Strand, an early word for shore.

Climate

Barnstaple has cool, wet winters and mild, wet summers. Mean high temperatures range from 9 C (48 F) in January to 21 C (70 F) in July. October is the wettest month with 103 mm (4.1 in) of rain. The record high is 34 C (94 F) and the record low −9 C (16 F). Barnstaple gets an average of 862 mm (33.9 in) of rain per year, with rain on 138 days.

| Climate data for Barnstaple, United Kingdom | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16 (61) |

18 (64) |

20 (68) |

25 (77) |

27 (81) |

32 (90) |

33 (91) |

34 (93) |

28 (82) |

29 (84) |

18 (64) |

15 (59) |

34 (93) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9 (48) |

10 (50) |

11 (52) |

13 (55) |

18 (64) |

19 (66) |

21 (70) |

20 (68) |

19 (66) |

15 (59) |

12 (54) |

9 (48) |

15 (58) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 4 (39) |

4 (39) |

5 (41) |

6 (43) |

9 (48) |

11 (52) |

13 (55) |

13 (55) |

11 (52) |

9 (48) |

6 (43) |

4 (39) |

8 (46) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −6 (21) |

−6 (21) |

−9 (16) |

−3 (27) |

0 (32) |

1 (34) |

7 (45) |

7 (45) |

−1 (30) |

−2 (28) |

−6 (21) |

−6 (21) |

−9 (16) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 75 (3.0) |

65 (2.6) |

53 (2.1) |

64 (2.5) |

60 (2.4) |

63 (2.5) |

64 (2.5) |

65 (2.6) |

59 (2.3) |

103 (4.1) |

93 (3.7) |

98 (3.9) |

862 (34.2) |

| Average rainy days | 15 | 10 | 12 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 138 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 83 | 82 | 80 | 77 | 76 | 78 | 79 | 79 | 79 | 81 | 83 | 83 | 80 |

| Source 1: Weather2[21] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: HolidayCheck.com[22] | |||||||||||||

Demography

Barnstaple parish's population in the 1801 census was 3,748, in the 1901 census 9,698, and in the 2001 census, the population was 22,497.[23]

As of 2011, the racial make-up of the town was as follows:[24]

- White British 93.9%

- White Irish 0.3%

- Other White 2.6%

- Mixed race 1.2%

- Asian 1.6%

- Black 0.3%

- Other 0.1%

As a major town, Barnstaple is more ethnically diverse than the North Devon district (95.9% White British) and Devon as a whole (94.2% White British). Barnstaple has a similar ethnic make-up to other south-west towns such as Truro and Cullompton.

Economy

North Devon is some distance from the UK's traditional areas of industrial activity and population. In the late 1970s Barnstaple gained a number of industrial companies due to the availability of central government grants for opening factories and operating them on low or zero levels of local taxation. This was only partially successful, with few lasting more than the few years that grants were available. One success was the manufacturing of generic medicines by Cox Pharmaceuticals (now branded Allergan), which moved in 1980 from its site in Brighton, Sussex. A lasting effect on the town has been the development and expansion of industrial estates at Seven Brethren, Whiddon Valley and Pottington.

Whilst the 1989 opening of the improved A361 connection to the motorway network helped in some ways to promote trade, notably weekend tourism, it was detrimental to some distribution businesses. The latter had previously viewed the town as a base for local distribution networks, a need that was removed when the travelling time to the M5 motorway roughly halved.

Because Barnstaple is the main shopping area for North Devon, retail work contributes to the economy. There are many generic chain stores in the town centre and in the Roundswell Business Park, on the western fringe of the town. Tesco has several stores in the area, including a Tesco Extra hypermarket and a large Tesco superstore. There are also Sainsbury's and Lidl supermarkets. The multi-million pound redevelopment in and around the former Leaderflush Shapland works at Anchorwood Bank is creating a conservation area near the River Taw, hundreds of new homes, and a commercial retail area with new shops, restaurants and leisure facilities. A new Asda superstore and petrol filling station are part of the redevelopment. The new Asda store opened in November 2016.

However, by far the largest employer in the region is local and central government. The two main governmental employers are the Royal Marines Base Chivenor, 3 miles (5 km) west of the town, and North Devon District Hospital, 1 mile (1.6 km) to the north.

In 2005 unemployment in North Devon was 1.8–2.4 per cent, and the median per capita wage for North Devon was 73 per cent of the UK national average. The level of work in the informal or casual sector is high, partly due to the impact of seasonal tourism, as is the case in much of the South West of England.

By 2018 unemployment in North Devon had fallen significantly from a 2010 high to 1.2 per cent, while median weekly full-time pay stood at £440 per week and average housing prices at £230,000. The number of businesses registered has increased by 370 since 2010 to 4895. The year 2018 also saw marked government investment in the area through Coastal Community grants and Housing Infrastructure funds £83 million to upgrade the North Devon Link Road.[25]

Twin towns and sister cities

Barnstaple is twinned with:

Landmarks

Barnstaple has an eclectic mix of architectural styles, with the 19th century probably now predominant. There are some remnants of early buildings as well as several early plaster ceilings. St. Anne's Chapel in the central churchyard is probably the best of the ancient buildings to survive. Queen Anne's Walk was erected c. 1708 as a mercantile exchange. The Georgian Guildhall is also of interest as well as the Pannier Market beneath. The museum has an "arts and crafts" vibe with its tessellated floors, locally made staircase and decorative fireplaces.[27]

Barnstaple Castle

A wooden castle was built by Geoffrey de Mowbray, Bishop of Coutances in the 11th century, clearing houses to make room for it. Juhel of Totnes later occupied the castle and founded Barnstaple Priory just outside its walls. The castle's first stone buildings were probably erected by Henry de Tracey, a strong supporter of King Stephen. In 1228, the Sheriff of Devon ordered the walls of the castle to be reduced to a height of 10 feet (3 m). By the time of the death of the last Henry de Tracey in 1274, the castle was beginning to decay. The fabric of the castle was used in the construction of other buildings and by 1326 the castle was a ruin. The remaining walls blew down in a storm in 1601.[28] Today only the tree covered motte remains.[29]

Another property, the Neo-Gothic Manor of Tawstock, originally known as Tawstock House, is two miles south of Barnstaple. It replaced an earlier Tudor mansion, built in 1574 but lost to a fire in 1787.

St Anne's Chapel

The Grade II listed St Anne's Chapel[30] was restored in 2012 and was being used as a community centre that was available for let as a venue that could accommodate 60 people.[31]

It was an ancient Gothic chantry chapel, the assets of which were acquired by the Mayor of Barnstaple and others in 1585, some time after the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The deed of feoffment dated 1 November 1585 exists in the George Grant Francis collection in Cardiff.[32]

The Pannier Market and Butchers' Row

Barnstaple has been the major market for North Devon since Saxon times. Demands for health regulation of its food market in Victorian times saw the construction in 1855–1856 of the town's Pannier Market, originally known as the Vegetable Market and designed by local architect R. D. Gould. The building has a high glass and timber roof on iron columns. At 107 yards (98 m) long, it runs the length of Butchers' Row. Market days are Monday – Crafts and General (April to December), Tuesday – General and Produce (all year), Wednesday – Arts Collectables and Books (all year), Thursday – Crafts and General (all year), Friday – General and Produce (all year), and Saturday – General and Produce (all year).

Built on the other side of the street at the same time as the Pannier Market, Butchers' Row consists of ten shops with pilasters of Bath Stone, and wrought iron supports to an overhanging roof. Only one of the shops remains as a butchers,[33] although the new shops still sell local agricultural goods. There is one baker, one delicatessen, two fishmongers, a florist and a greengrocer.

As of early 2020, the local Council's web site provided this summary for the Pannier Market: "Largely unchanged in over 150 years, Barnstaple's historic Pannier Market has a wide range of stalls, with everything from fresh local produce, flowers and crafts, to prints and pictures, fashion and... two cafés".[34]

The "Pannier Market, Butchers Row" has been Grade II listed since 1951.[35]

Others

| Key | |

| Abbey/Priory/Cathedral | |

| Accessible open space | |

| Amusement/Theme Park | |

| Castle | |

| Country Park | |

| English Heritage | |

| Forestry Commission | |

| Heritage railway | |

| Historic House | |

| Mosques | |

| Museum (free/not free) | |

| National Trust | |

| Theatre | |

| Zoo | |

In Barnstaple

- Albert Clock in The Square

- Barnstaple Cemetery, the town's burial ground

- Barnstaple Heritage Trail

- Businesses and Markets

- Barnstaple Town F.C.

- North Devon Crematorium, the largest crematorium in England, Wales and Northern Ireland

- Penrose's Almshouses

Around Barnstaple

Transport

In 1989, the A361 North Devon Link Road was constructed, linking Barnstaple with the M5 motorway, approximately 40 miles (65 km) to the east. Traffic congestion in the town used to be severe, but in May 2007, the Barnstaple Western Bypass was opened so traffic heading towards Braunton and Ilfracombe avoids travelling through the town centre over the ancient bridge. The bypass consists of 1.6 miles (2.6 km) of new road and a 447 yards (409 m) long, five-span bridge. It was expected to have cost £42 million.[36] As part of this work, the town's main square was re-modelled as the entrance to the town centre, and The Strand was closed to traffic. The A39, the Atlantic Highway, follows after the A361 to Bideford and to Bude and then further down towards Cornwall.

The Barnstaple bus network is privatised and run by many bus operators including Stagecoach South West & Filers. The main bus station is located on the junction with Queen Street and Belle Meadow Drive.

Following frequent bus services operate from Barnstaple:

- 19 roundswell – Barnstaple bus station- North Devon Hospital

- 21 Westward Ho! – Bideford – Fremington – Barnstaple – Braunton – West Meadow Road/Ilfracombe

- 21A Appledore – bideford – Fremington – Barnstaple – Braunton – West Meadow Road/ georgeham

21C Barnstaple – Braunton – Croyde – Georgeham

- 71 Barnstaple – Torrington – (Holsworthy)/Shebbear

- 155 Barnstaple – South Molton – Tiverton – Exeter

- 301 Barnstaple – Ilfracombe – Combe Martin

- 309/310 Barnstaple – Lynton – Lynmouth

National Express services to London, Heathrow Airport, Taunton, Bristol and Birmingham also run services from Barnstaple.

The nearest airport is Exeter Airport.

Railway

Barnstaple railway station is the terminus of a branch line from Exeter, known as the Tarka Line after the local connection with Tarka the Otter. The station is near the end of the Long Bridge but on the opposite bank of the River Taw to the town centre. The town used to have several other stations but these have all closed since the publication of the Reshaping of British Railways (the so-called Beeching Axe) report in the 1960s. The surviving station was opened on 1 August 1854 by the North Devon Railway (later the London and South Western Railway), although a service had operated from Fremington since 1848 for goods traffic only. The station became "Barnstaple Junction" on 20 July 1874 when the railway opened the branch line through to Ilfracombe, reverting to just plain "Barnstaple" again when this was closed on 5 October 1970. It is now a terminus and much reduced in size as part of the site is now used for the Barnstaple Western Bypass.

The Ilfracombe branch line brought the railway across the river into the town centre. Barnstaple Quay was situated close by the Castle Mound. It was closed in 1898 and replaced by a nearby Barnstaple Town station at North Walk which was also the terminus of the narrow gauge Lynton and Barnstaple Railway until this closed in 1935. The narrow gauge line's main depot and operating centre was at nearby Pilton.

A separate "Barnstaple" station, renamed Barnstaple (Victoria Road) in 1949, was opened to the east of the town in 1873 as the terminus of the Devon and Somerset Railway, eventually a part of the Great Western Railway. A junction was later provided to allow trains access to Barnstaple Junction and these ran through to Ilfracombe. It was closed in 1970.

Education

There are a selection of well-regarded primary and secondary state schools and a tertiary college in Barnstaple.

In 2012, the county of Devon 58%[37] of students achieved 5 GCSEs grade A*to C. The UK average is 59%.[37]

| School Name | Type | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Park Community School | State | 38% | 44% | 45% | 47% | 54% | [38] |

| Pilton Community College | State | 47% | 51% | 50% | 53% | 49% | [39] |

Petroc (formerly North Devon College) is a large tertiary college providing a wide range of vocational and academic further education for more than 3,000 young people over 16. The college was due to spend £100 million on a new campus, to be opened on Seven Brethren in 2011,[40][41] but this fell through when the LSC removed its £75 million funding in January 2009.[42]

Petroc was launched in September 2009 – a year after NDC merged with Tiverton's East Devon College.[43]

Religious sites

St Peter's Church is the parish church of Barnstaple. Its oldest parts probably date to the 13th century, though the nave, chancel and tower date from 1318, when three altars[44] were dedicated by Bishop Stapledon. The north and south aisles were added in c. 1670. The church has a notable broach spire, claimed by W. G. Hoskins to be the best of its kind in the country.[11] Inside the church are many mural monuments to 17th-century merchants, such as Raleigh Clapham (died 1636), George Peard (died 1644) and Thomas Horwood (died 1658), reflecting the prosperity of the town at that time.[15] The interior of the church was heavily restored by George Gilbert Scott from 1866, and then by his son John Oldrid Scott into the 1880s,[15] leaving it "dark and dull", according to Hoskins.[11]

Other religious buildings in the town include St Anne's Chapel (a 14th-century chantry chapel, now a museum) in the parish churchyard; the Church of St Mary the Virgin in the suburb of Pilton is 13th-century and a Grade I listed building; Holy Trinity, built in the 1840s but necessarily rebuilt in 1867 as its foundations were unsound – it has a fine tower in the Somerset style; the Roman Catholic church of the Immaculate Conception, said to have been built to designs supplied by Pugin, in Romanesque Revival style; the late 19th-century church of St John the Baptist in the Newport area of the town and a Baptist chapel of 1870 which includes a lecture hall and classrooms.[11][15]

Sport

Cricket is played at Barnstaple and Pilton.[45] Barnstaple Town F.C. have been based at Mill Road since 1904 and play in the Western Football League.

Rugby union is played at Barnstaple Rugby Football Club[46] whose first team play in South West Premier, which is a fifth tier league in the English rugby union system.

More sports are available at the North Devon Leisure Centre,[47] which is the home of Barnstaple Squash Club.[48]

There are numerous bowling greens and tennis courts, including those at the Tarka Tennis Centre, which has six indoor courts and which hosts the Aegon GB Pro-Series Barnstaple.[49] In February 2010 a Cornish Pilot Gig Rowing Club was established, bringing this sport to Castle Quay in the centre of Barnstaple.[50]

There is hockey available. Taw Valley Ladies Hockey Club (as well as a Junior set-up) and North Devon Men's Hockey Club – they both play at Park School.

Notable people

In birth order:

- Henry de Bracton (c. 1210 – c. 1258), cleric and jurist, was appointed Archdeacon of Barnstaple in 1264.

- Robert Carey (1515–1586), landowner, became Barnstaple MP in 1553, Sheriff of Devon in 1555–1556 and Recorder of Barnstaple from 1560.

- Richard Ferris (died 1649), merchant and MP for Barnstaple from 1640, founded Barnstaple Grammar School.

- Pentecost Dodderidge (died c. 1650), was elected MP for Barnstaple in 1621, 1624 and 1625.

- Richard Callicott (1604–1686), born in Barnstaple, was a leader of Massachusetts Bay Colony.

- John Dodderidge (1610–1659), was elected MP for Barnstaple in 1646 and 1652.

- John Loosemore (1618–1681), born in Barnstaple, was a noted builder of pipe organs, including the one in Exeter Cathedral.

- John Gay (1685–1732), poet and dramatist

- James Parsons (1705–1770), physician, antiquary and prolific medical author born in Barnstaple

- Henry Fry (1826–1892), born in Barnstaple, was a politician and merchant in British Columbia.

- William Hoyle (1842–1918), born in Barnstaple, became a politician and furniture maker in Ontario.

- Francis Carruthers Gould (1844–1925), caricaturist and cartoonist, was born in Barnstaple.

- Fred M. White (1859–1935), author of science-fiction and disaster novels, spent his old age in Barnstaple and set three of his novels there.

- Hubert Bath (1883–1945), born in Barnstaple, composed musical scores for many films in the 1920s and 1930s.

- Francis Chichester (1901–1972), pioneering aviator and solo sailor

- George Hart (1902–1987), first-class cricketer with Middlesex, died in Barnstaple

- Stafford Somerfield (1911–1995), News of the World editor, was born in Barnstaple.

- Brian Thomas (1912–1989), an artist best known for church paintings, born in Barnstaple

- Racey Helps (1913–1970), children's writer and illustrator, lived in the town from 1962 until his death.

- Jeremy Thorpe (1929–2014), Liberal Party leader, sat as MP for North Devon constituency centred on Barnstaple in 1959–1978.

- Nigel Brooks (born 1936), born in Barnstaple, is a musical composer and served as conductor of the BBC Concert Orchestra.

- Johnny Kingdom (1939–2018), wildlife film-maker and photographer

- John Keay (born 1941), historian and radio presenter born in Barnstaple

- Richard Eyre (born 1943), a film, theatre, television and opera director, was born in Barnstaple.

- Tim Wonnacott (born 1951), antiques expert and television presenter

- Dermot Murnaghan (born 1957), Sky News television broadcaster, was born in Barnstaple.

- Anne-Marie Dawe (born 1968), born in Barnstaple, became the RAF's first fully qualified female navigator in 1991.

- Phil Vickery (born 1976), rugby player

- Stuart Brennan (born 1982), BAFTA winning actor

- George Friend (born 1987), professional footballer born in Barnstaple

- Andy King (born 1988), professional footballer born in Barnstaple

Notes

- Museum of Barnstaple and North Devon has no information, whether regarding provenance, date or subject matter, on this very large painting hanging on the wall of the first floor, which dominates the staircase of the museum building in Barnstaple.

- Richard Beaple (died 1643), three times Mayor; Richard Ferris (Mayor in 1632), who together with Alexander Horwood, received a payment from the Corporation of Barnstaple in 1630 for "riding to Exeter about the Spanish Company".[13]

- The royal charter of 1605 which re-established the Spanish Company names several hundred founding members from named English ports, the Barnstaple members being: William Gay, John Salisbury, John Darracott, John Mewles, George Gay, Richard Dodderidge, James Beaple, Nicholas Downe, James Downe, Robert Dodderidge, Richard Beaple and Pentecost Dodderidge, "merchants of Barnstaple". Richard Dodderidge and James Beaple were named as amongst the "first and present assistants and chief councillors of the fellowship".[12]

References

- Pointon, G. E., ed. (1983) BBC Pronouncing Dictionary of British Names; 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; p. 18 (only the latter pronunciation)

- "Barnstaple (Parish, United Kingdom) – Population Statistics, Charts, Map and Location". citypopulation.de. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- "Barnstaple (Devon, South West England, United Kingdom) – Population Statistics, Charts, Map, Location, Weather and Web Information". citypopulation.de. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- "Barnstaple profile". Communities. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Watts, Victor (2010). The Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-names (1st paperback ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-0-521-16855-7.

- Hingeston-Randolph, F. C., ed. Episcopal Registers: Diocese of Exeter. 10 vols. London: George Bell, 1886–1915 (for the period 1257 to 1455)

- Harris, Helen (2004). A Handbook of Devon Parishes. Tiverton: Halsgrove. pp. 13–15. ISBN 1-84114-314-6.

- Todd, Malcolm (1987). The South West to AD 1000. A Regional History of England. Longman. p. 276. ISBN 0-582-49274-2.

- Lamplugh, L., Barnstaple: Town on the Taw, 2002, Cullompton, p. 9

- Kowaleski, Maryanne (1992). "The Port Towns of Fourteenth-Century Devon". In Michael Duffy; et al. (eds.). The New Maritime History of Devon Volume 1. From early times to the late eighteenth century. London: Conway Maritime Press. p. 64. ISBN 0-85177-611-6.

- Hoskins, W. G. (1972). A New Survey of England: Devon (New ed.). London: Collins. pp. 327–330. ISBN 0-7153-5577-5.

- Croft, Pauline, The Spanish Company, London Record Society, Volume 9, London, 1973

- Lamplugh, p. 165, note 2 to chapter 12, quoting "Borough Records Vol II, p. 150"

- Lamplugh, p. 165, note 2 to chapter 12.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Cherry, Bridget (revision) (1989) [1952]. The Buildings of England: Devon. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 148–160. ISBN 0-14-071050-7.

- Wikisource:1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Barnstaple

- "19, Bear Street". British listed buildings. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- See further: Oliver, W. Bruce, Barnstaple Borough, Transactions of the Devon Association, vol. 62, (1930) pp.269–273

- History of Parliament: Barnstaple

- "Barnstaple Town Council". Archived from the original on 25 January 2001.

- "Climate Profile for Barnstaple". August 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- "Temperature Barnstaple – climate Barnstaple England – weather Barnstaple". August 2011. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- Office for National Statistics. Barnstaple (Parish): Ethnic Group, 2001

- Office for National Statistics. Barnstaple (Parish): Ethnic Group, 2011

- House of Commons Library

- "British towns twinned with French towns". Archant Community Media Ltd. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- "Some Men who Made Barnstaple..." 2010 by Pauline Brain

- Ford, David Nash. "History of Barnstaple Castle in Devon". Britannia.com. Archived from the original on 9 October 2007. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- Fry, Plantagenet Somerset (1980). The David & Charles Book of Castles. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. p. 184. ISBN 0-7153-7976-3.

- Church of St Anne

- St. ANNE'S ARTS & COMMUNITY CENTRE

- RISW GGF 1/122 Feoffment, dated 1 Nov 1585. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Gussin, Tony (6 October 2016). "Grattons in Butchers Row closes down after 60 years". North Devon Gazette.

- Pannier Market

- [https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1385084 PANNIER MARKET[

- "Barnstaple Western Bypass". Devon County Council. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- Rogers, Simon (24 January 2013). "Secondary School League Tables". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- "Education | Park School". DFE. 27 February 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- "Pilton Community College". DFE. 27 February 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- "£100M Funds Go-Ahead For College". BBC News. 31 January 2008. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- "Our New College: Planning". North Devon College. Archived from the original on 3 March 2009.

- "Projects threatened by £56m cuts". BBC News. 8 June 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- Montgomery, Angus (23 September 2009). "Interbrand renames North Devon College as Petroc". Marketing Week. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- Pevsner, p.150

- Play-Sport New Media (13 June 2002). "Play-Cricket the ECB Cricket Network". Barnpilcc.play-cricket.com. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- "Official Website for Barnstaple Rugby Club". Barnstaple RFC. 9 January 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- "North Devon Leisure Centre| Gym, Swimming Pool, Group Exercise Studio, Sports Hall, Squash Courts, Dojo – Martial Arts room | Devon, United Kingdom". Leisurecentre.com. Archived from the original on 20 November 2008. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- "Welcome to Barnstaple Squash Club". Barnstaplesquash.co.uk. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- "Tarka Tennis indoor center Barnstaple North Devon". Tarkatennis.net. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- "Barnstaple Pilot Gig Club". Barnstaple Pilot Gig Club. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Barnstaple. |