Rumination syndrome

Rumination syndrome, or merycism, is a chronic motility disorder characterized by effortless regurgitation of most meals following consumption, due to the involuntary contraction of the muscles around the abdomen.[1] There is no retching, nausea, heartburn, odour, or abdominal pain associated with the regurgitation, as there is with typical vomiting, and the regurgitated food is undigested. The disorder has been historically documented as affecting only infants, young children, and people with cognitive disabilities (the prevalence is as high as 10% in institutionalized patients with various mental disabilities). It is increasingly being diagnosed in a greater number of otherwise healthy adolescents and adults, though there is a lack of awareness of the condition by doctors, patients and the general public.

| Rumination syndrome | |

|---|---|

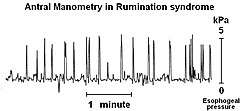

| |

| A postprandial manometry of a patient with rumination syndrome showing intra-abdominal pressure. The "spikes" are characteristic of the abdominal wall contractions responsible for the regurgitation in rumination. | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

Rumination syndrome presents itself in a variety of ways, with especially high contrast existing between the presentation of the typical adult sufferer without a mental disability and the presentation of an infant and/or mentally impaired sufferer. Like related gastrointestinal disorders, rumination can adversely affect normal functioning and the social lives of individuals. It has been linked with depression.

Little comprehensive data regarding rumination syndrome in otherwise healthy individuals exists because most sufferers are private about their illness and are often misdiagnosed due to the number of symptoms and the clinical similarities between rumination syndrome and other disorders of the stomach and esophagus, such as gastroparesis and bulimia nervosa. These symptoms include the acid-induced erosion of the esophagus and enamel, halitosis, malnutrition, severe weight loss and an unquenchable appetite. Individuals may begin regurgitating within a minute following ingestion, and the full cycle of ingestion and regurgitation can mimic the binging and purging of bulimia.

Diagnosis of rumination syndrome is non-invasive and based on a history of the individual. Treatment is promising, with upwards of 85% of individuals responding positively to treatment, including infants and the mentally disabled.

Signs and symptoms

While the number and severity of symptoms vary among individuals, repetitive regurgitation of undigested food (known as rumination) after the start of a meal is always present.[2][3] In some individuals, the regurgitation is small, occurring over a long period of time following ingestion, and can be rechewed and swallowed. In others, the amount can be bilious and short lasting, and must be expelled. While some only experience symptoms following some meals, most experience episodes following any ingestion, from a single bite to a large meal.[4] However, some long-term patients will find a select couple of food or drink items that do not trigger a response.

Unlike typical vomiting, the regurgitation is typically described as effortless and unforced.[2] There is seldom nausea preceding the expulsion, and the undigested food lacks the bitter taste and odour of stomach acid and bile.[2]

Symptoms can begin to manifest at any point from the ingestion of the meal to 120 minutes thereafter.[3] However, the more common range is between 30 seconds to 1 hour after the completion of a meal.[4] Symptoms tend to cease when the ruminated contents become acidic.[2][4]

Abdominal pain (38.1%), lack of fecal production or constipation (21.1%), nausea (17.0%), diarrhea (8.2%), bloating (4.1%), and dental decay (3.4%) are also described as common symptoms in day-to-day life.[3] These symptoms are not necessarily prevalent during regurgitation episodes, and can happen at any time. Weight loss is often observed (42.2%) at an average loss of 9.6 kilograms, and is more common in cases where the disorder has gone undiagnosed for a longer period of time,[3] though this may be expected of the nutrition deficiencies that often accompany the disorder as a consequence of its symptoms.[3] Depression has also been linked with rumination syndrome,[5] though its effects on rumination syndrome are unknown.[2]

Acid erosion of the teeth can be a feature of rumination,[6] as can halitosis (bad breath).[7]

Causes

The cause of rumination syndrome is unknown. However, studies have drawn a correlation between hypothesized causes and the history of patients with the disorder. In infants and the cognitively impaired, the disease has normally been attributed to over-stimulation and under-stimulation from parents and caregivers, causing the individual to seek self-gratification and self-stimulus due to the lack or abundance of external stimuli. The disorder has also commonly been attributed to a bout of illness, a period of stress in the individual's recent past, and to changes in medication.[2]

In adults and adolescents, hypothesized causes generally fall into one of either category: habit-induced, and trauma-induced. Habit-induced individuals generally have a history of bulimia nervosa or of intentional regurgitation (magicians and professional regurgitators, for example), which though initially self-induced, forms a subconscious habit that can continue to manifest itself outside the control of the affected individual. Trauma-induced individuals describe an emotional or physical injury (such as recent surgery, psychological distress, concussions, deaths in the family, etc.), which preceded the onset of rumination, often by several months.[2][3]

Pathophysiology

Rumination syndrome is a poorly understood disorder, and a number of theories have speculated the mechanisms that cause the regurgitation,[3] which is a unique symptom to this disorder. While no theory has gained a consensus, some are more notable and widely published than others.[2]

The most widely documented mechanism is that the ingestion of food causes gastric distention, which is followed by abdominal compression and the simultaneous relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). This creates a common cavity between the stomach and the oropharynx that allows the partially digested material to return to the mouth. There are several offered explanations for the sudden relaxation of the LES.[8] Among these explanations is that it is a learned voluntary relaxation, which is common in those with or having had bulimia. While this relaxation may be voluntary, the overall process of rumination is still generally involuntary. Relaxation due to intra-abdominal pressure is another proposed explanation, which would make abdominal compression the primary mechanism. The third is an adaptation of the belch reflex, which is the most commonly described mechanism. The swallowing of air immediately prior to regurgitation causes the activation of the belching reflex that triggers the relaxation of the LES. Patients often describe a feeling similar to the onset of a belch preceding rumination.[2]

Diagnosis

Rumination syndrome is diagnosed based on a complete history of the individual. Costly and invasive studies such as gastroduodenal manometry and esophageal Ph testing are unnecessary and will often aid in misdiagnosis.[2] Based on typical observed features, several criteria have been suggested for diagnosing rumination syndrome.[3] The primary symptom, the regurgitation of recently ingested food, must be consistent, occurring for at least six weeks of the past twelve months. The regurgitation must begin within 30 minutes of the completion of a meal. Patients may either chew the regurgitated matter or expel it. The symptoms must stop within 90 minutes, or when the regurgitated matter becomes acidic. The symptoms must not be the result of a mechanical obstruction, and should not respond to the standard treatment for gastroesophageal reflux disease.[2]

In adults, the diagnosis is supported by the absence of classical or structural diseases of the gastrointestinal system. Supportive criteria include a regurgitant that does not taste sour or acidic,[8] is generally odourless, is effortless,[4] or at most preceded by a belching sensation,[2] that there is no retching preceding the regurgitation,[2] and that the act is not associated with nausea or heartburn.[2]

Patients visit an average of five physicians over 2.75 years before being correctly diagnosed with rumination syndrome.[9]

Differential diagnosis

Rumination syndrome in adults is a complicated disorder whose symptoms can mimic those of several other gastroesophogeal disorders and diseases. Bulimia nervosa and gastroparesis are especially prevalent among the misdiagnoses of rumination.[2]

Bulimia nervosa, among adults and especially adolescents, is by far the most common misdiagnosis patients will hear during their experiences with rumination syndrome. This is due to the similarities in symptoms to an outside observer—"vomiting" following food intake—which, in long-term patients, may include ingesting copious amounts to offset malnutrition, and a lack of willingness to expose their condition and its symptoms. While it has been suggested that there is a connection between rumination and bulimia,[9][10] unlike bulimia, rumination is not self-inflicted. Adults and adolescents with rumination syndrome are generally well aware of their gradually increasing malnutrition, but are unable to control the reflex. In contrast, those with bulimia intentionally induce vomiting, and seldom re-swallow food.[2]

Gastroparesis is another common misdiagnosis.[2] Like rumination syndrome, patients with gastroparesis often bring up food following the ingestion of a meal. Unlike rumination, gastroparesis causes vomiting (in contrast to regurgitation) of food, which is not being digested further, from the stomach. This vomiting occurs several hours after a meal is ingested, preceded by nausea and retching, and has the bitter or sour taste typical of vomit.[4]

Classification

Rumination syndrome is a condition which affects the functioning of the stomach and esophagus, also known as a functional gastroduodenal disorder.[11] In patients that have a history of eating disorders, Rumination syndrome is grouped alongside eating disorders such as bulimia and pica, which are themselves grouped under non-psychotic mental disorder. In most healthy adolescents and adults who have no mental disability, Rumination syndrome is considered a motility disorder instead of an eating disorder, because the patients tend to have had no control over its occurrence and have had no history of eating disorders.[12][13]

Treatment and prognosis

There is presently no known cure for rumination. Proton pump inhibitors and other medications have been used to little or no effect.[14] Treatment is different for infants and the mentally handicapped than for adults and adolescents of normal intelligence. Among infants and the mentally handicapped, behavioral and mild aversion training has been shown to cause improvement in most cases.[15] Aversion training involves associating the ruminating behavior with negative results, and rewarding good behavior and eating. Placing a sour or bitter taste on the tongue when the individual begins the movements or breathing patterns typical of his or her ruminating behavior is the generally accepted method for aversion training,[15] although some older studies advocate the use of pinching. In patients of normal intelligence, rumination is not an intentional behavior and is habitually reversed using diaphragmatic breathing to counter the urge to regurgitate.[14] Alongside reassurance, explanation and habit reversal, patients are shown how to breathe using their diaphragms prior to and during the normal rumination period.[14][16] A similar breathing pattern can be used to prevent normal vomiting. Breathing in this method works by physically preventing the abdominal contractions required to expel stomach contents.

Supportive therapy and diaphragmatic breathing has shown to cause improvement in 56% of cases, and total cessation of symptoms in an additional 30% in one study of 54 adolescent patients who were followed up 10 months after initial treatments.[3] Patients who successfully use the technique often notice an immediate change in health for the better.[14] Individuals who have had bulimia or who intentionally induced vomiting in the past have a reduced chance for improvement due to the reinforced behavior.[9][14] The technique is not used with infants or young children due to the complex timing and concentration required for it to be successful. Most infants grow out of the disorder within a year or with aversive training.[17]

Epidemiology

Rumination disorder was initially documented[17][18] as affecting newborns,[13] infants, children[12] and individuals with mental and functional disabilities (the cognitively handicapped).[18][19] It has since been recognized to occur in both males and females of all ages and cognitive abilities.[2][20]

Among the cognitively handicapped, it is described with almost equal prevalence among infants (6–10% of the population) and institutionalized adults (8–10%).[2] In infants, it typically occurs within the first 3–12 months of age.[17]

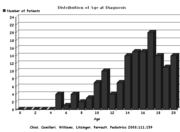

The occurrence of rumination syndrome within the general population has not been defined.[11] Rumination is sometimes described as rare,[2] but has also been described as not rare, but rather rarely recognized.[21] The disorder has a female predominance.[11] The typical age of adolescent onset is 12.9, give or take 0.4 years (±), with males affected sooner than females (11.0 ± 0.8 for males versus 13.8 ± 0.5 for females).[3]

There is little evidence concerning the impact of hereditary influence in rumination syndrome.[8] However, case reports involving entire families with rumination exist.[22]

History

The term rumination is derived from the Latin word ruminare, which means to chew the cud.[22] First described in ancient times, and mentioned in the writings of Aristotle, rumination syndrome was clinically documented in 1618 by Italian anatomist Fabricus ab Aquapendente, who wrote of the symptoms in a patient of his.[20][22]

Among the earliest cases of rumination was that of a physician in the nineteenth century, Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard, who acquired the condition as the result of experiments upon himself. As a way of evaluating and testing the acid response of the stomach to various foods, the doctor would swallow sponges tied to a string, then intentionally regurgitate them to analyze the contents. As a result of these experiments, the doctor eventually regurgitated his meals habitually by reflex.[23]

Numerous case reports exist from before the twentieth century, but were influenced greatly by the methods and thinking used in that time. By the early twentieth century, it was becoming increasingly evident that rumination presented itself in a variety of ways in response to a variety of conditions.[20] Although still considered a disorder of infancy and cognitive disability at that time, the difference in presentation between infants and adults was well established.[22]

Studies of rumination in otherwise healthy adults became decreasingly rare starting in the 1900s, and the majority of published reports analyzing the syndrome in mentally healthy patients appeared thereafter. At first, adult rumination was described and treated as a benign condition. It is now described as otherwise.[24] While the base of patients to examine has gradually increased as more and more people come forward with their symptoms, awareness of the condition by the medical community and the general public is still limited.[2][21][25][26]

In other animals

The chewing of cud by animals such as cows, goats, and giraffes is considered normal behavior. These animals are known as ruminants.[8] Such behavior, though termed rumination, is not related to human rumination syndrome, but is ordinary. Involuntary rumination, similar to what is seen in humans, has been described in gorillas and other primates.[27] Macropods such as kangaroos also regurgitate, re-masticate, and re-swallow food, but these behaviors are not essential to their normal digestive process, are not observed as predictably as the ruminants', and hence were termed "merycism" in contrast with "true rumination".[28]

See also

References

- Rumination Syndrome — Diagnosis and Treatment Options at Mayo Clinic

- Papadopoulos, Vassilios; Mimidis, Konstantinos (July–September 2007), "The rumination syndrome in adults: A review of the pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment", Journal of Postgraduate Medicine, 53 (3): 203–206, doi:10.4103/0022-3859.33868, PMID 17699999

- Chial, Heather J; Camilleri, Michael; Williams, Donald E; Litzinger, Kristi; Perrault, Jean (2003), "Rumination syndrome in children and adolescents: diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis", Pediatrics, 111 (1): 158–162, doi:10.1542/peds.111.1.158, PMID 12509570

- Camilleri, Michael; Seime, Richard J, Rumination Syndrome, symptoms, Rochester, Minnesota: Mayo Clinic, retrieved 2009-06-26

- Amarnath RP, Abell TL, Malagelada JR (October 1986), "The rumination syndrome in adults. A characteristic manometric pattern.", Annals of Internal Medicine, 105 (4): 513–518, doi:10.7326/0003-4819-105-4-513, PMID 3752757

- Adrian Lussi (2006). Dental erosion from diagnosis to therapy; 22 tables. Basel: Karger. p. 120. ISBN 9783805580977.

- Carey WB, Crocker AC, Coleman WL, Feldman HM, Elias ER (2009). Developmental-behavioral pediatrics (4th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 634. ISBN 9781416033707.

- Ellis, Cynthia R; Schnoes, Connie J (2009), "Eating Disorder, Rumination", Medscape Pediatrics, retrieved 2009-09-07

- LaRocca, Felix E; Della-Fera, Mary-Anne (October 1986), "Rumination: Its significance in adults with bulimia nervosa", Psychosomatics, 27 (3): 209–212, doi:10.1016/s0033-3182(86)72713-8, PMID 3457391

- O'Brien, Michael D; Bruce, Barbara K; Camilleri, Michael (March 1995), "The rumination syndrome: Clinical features rather than manometric diagnosis", Gastroenterology, 108 (4): 1024–1029, doi:10.1016/0016-5085(95)90199-X, PMID 7698568

- Tack, Jan; Talley, Nicholas J; Camilleri, Michael; Holtmann, Gerald; Hu, Pinjin; Malagelada, Juan-R; Stanghellini, Vincenzo (2006), "Functional gastroduodenal disorders" (PDF), Gastroenterology, 130 (5): 1466–1479, doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.059, PMID 16678560

- ICD-10 entries for rumination syndrome - F98.2, retrieved 2009-08-10

- ICD-10 entries for rumination syndrome - P92.1, retrieved 2009-08-10

- Chitkara, Denesh K; van Tilburg, Miranda; Whitehead, William E; Talley, Nicholas (2006), "Teaching diaphragmatic breathing for rumination syndrome", The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 101 (11): 2449–2452, PMID 17090274

- Wagaman, JR; Williams, DE; Camilleri, M (1998), "Behavioral intervention for the treatment of rumination", Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 27 (5): 596–598, doi:10.1097/00005176-199811000-00019, PMID 9822330

- Johnson, WG; Corrigan, SA; Crusco, AH; Jarell, MP (1987), "Behavioral assessment and treatment of postprandial regurgitation", Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 9 (6): 679–684, doi:10.1097/00004836-198712000-00013, PMID 3443732

- Rasquin-Weber, A; Hyman, PE; Cucchiara, S; Fleisher, DR; Hyams, JS; Milla, PJ; Staiano, A (1999), "Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders", Gut, 45 (Supplement 2) (Suppl 2): 1160–1168, doi:10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii60, PMC 1766693, PMID 10457047

- Sullivan, PB (1997), "Gastrointestinal problems in the neurologically impaired child", Baillière's Clinical Gastroenterology, 11 (3): 529–546, doi:10.1016/S0950-3528(97)90030-0, PMID 9448914

- Rogers, B; Stratton, P; Victor, J; Cennedy, B; Andres, M (1992), "Chronic regurgitation among persons with mental retardation: A need for combined medical and interdisciplinary strategies", American Journal of Mental Retardation, 96 (5): 522–527, PMID 1562309

- Olden, Kevin W (2001), "Rumination", Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology, 4 (4): 351–358, doi:10.1007/s11938-001-0061-z, PMID 11469994, archived from the original on February 15, 2012

- Fox, Mark; Young, Alasdair; Anggiansah, Roy; Anggiansah, Angela; Sanderson, Jeremy (2006), "A 22 year old man with persistent regurgitation and vomiting: case outcome", British Medical Journal, 333 (7559): 133, discussion 134–7, doi:10.1136/bmj.333.7559.133, PMC 1502216, PMID 16840471

- Brockbank, EM (1907), "Merycism or Rumination in Man", British Medical Journal, 1 (2408): 421–427, doi:10.1136/bmj.1.2408.421, PMC 2356806, PMID 20763087

- Kanner, L (February 1936), "Historical notes on rumination in man", Medical Life, 43 (2): 27–60, OCLC 11295688

- Sidhu, Shawn S; Rick, James R (2009), "Erosive eosinophilic esophagitis in rumination syndrome", Jefferson Journal of Psychiatry, 22 (1), doi:10.29046/JJP.022.1.002, ISSN 1935-0783

- Camilleri, Michael; Seime, Richard J, Rumination Syndrome, an overview, Rochester, Minnesota: Mayo Clinic, retrieved 2009-06-26

- Parry-Jones, B (1994), "Merycism or rumination disorder. A historical investigation and current assessment", British Journal of Psychiatry, 165 (3): 303–314, doi:10.1192/bjp.165.3.303, PMID 7994499

- Hill, SP (May 2009), "Do gorillas regurgitate potentially-injurious stomach acid during 'regurgitation and reingestion?'", Animal Welfare, 18 (2): 123–127, ISSN 0962-7286

- Vendl, C. et al. (2017). "Merycism in western grey (Macropus fuliginosus) and red kangaroos (Macropus rufus)". Mammalian Biology. 86: 21–26. doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2017.03.005.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Pediatrics - Rumination Syndrome - The Mayo Clinic. Website provides an overview of the effect of the disorder on children.

- Rumination disorder - Web MD. Provides a general overview of the disease.