Necrotizing enterocolitis

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is a medical condition where a portion of the bowel dies.[1] It typically occurs in newborns that are either premature or otherwise unwell.[1] Symptoms may include poor feeding, bloating, decreased activity, blood in the stool, or vomiting of bile.[1][2]

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | |

|---|---|

| |

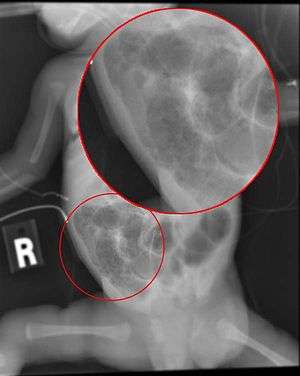

| Radiograph of a baby with necrotizing enterocolitis | |

| Specialty | Pediatrics, gastroenterology, neonatology |

| Symptoms | Poor feeding, bloating, decreased activity, vomiting of bile[1] |

| Complications | Short-gut syndrome, intestinal strictures, developmental delay[2] |

| Causes | Unclear[1] |

| Risk factors | Preterm birth, congenital heart disease, birth asphyxia, exchange transfusion, prolonged rupture of membranes[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Sepsis, anal fissure, infectious enterocolitis, Hirschsprung disease[2][3] |

| Prevention | Breast milk, probiotics.[2] |

| Treatment | Bowel rest, nasogastric tube, antibiotics, surgery[2] |

| Prognosis | Risk of death 25%[1] |

The exact cause is unclear.[1] Risk factors include congenital heart disease, birth asphyxia, exchange transfusion, and premature rupture of membranes.[1] The underlying mechanism is believed to involve a combination of poor blood flow and infection of the intestines.[2] Diagnosis is based on symptoms and confirmed with medical imaging.[1]

Prevention includes the use of breast milk and probiotics.[2] Treatment includes bowel rest, orogastric tube, intravenous fluids, and intravenous antibiotics.[2] Surgery is required in those who have free air in the abdomen.[2] A number of other supportive measures may also be required.[2] Complications may include short-gut syndrome, intestinal strictures, or developmental delay.[2]

About 7% of those that are born premature develop necrotizing enterocolitis.[2] Onset is typically in the first four weeks of life.[2] Among those affected, about 25% die.[1] The sexes are affected equally frequently.[4] The condition was first described between 1888 and 1891.[4]

Signs and symptoms

The condition is typically seen in premature infants, and the timing of its onset is generally inversely proportional to the gestational age of the baby at birth (i.e., the earlier a baby is born, the later signs of NEC are typically seen).[5]

Initial symptoms include feeding intolerance and failure to thrive, increased gastric residuals, abdominal distension and bloody stools. Symptoms may progress rapidly to abdominal discoloration with intestinal perforation and peritonitis and systemic hypotension requiring intensive medical support.

Cause

The exact cause is unclear.[1] Risk factors include congenital heart disease, birth asphyxia, exchange transfusion, and premature rupture of membranes.[1]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually suspected clinically but often requires the aid of diagnostic imaging modalities, most commonly radiography. Specific radiographic signs of NEC are associated with specific Bell's stages of the disease:[6]

- Bell's stage 1 (suspected disease):

- Mild systemic disease (apnea, lethargy,[7] slowed heart rate, temperature instability)

- Mild intestinal signs (abdominal distention, increased gastric residuals, bloody stools)

- Non-specific or normal radiological signs

- Bell's stage 2 (definite disease):

- Mild to moderate systemic signs

- Additional intestinal signs (absent bowel sounds, abdominal tenderness)

- Specific radiologic signs (pneumatosis intestinalis or portal venous gas

- Laboratory changes (metabolic acidosis, too few platelets in the bloodstream)

- Bell's stage 3 (advanced disease):

- Severe systemic illness (low blood pressure)

- Additional intestinal signs (striking abdominal distention, peritonitis)

- Severe radiologic signs (pneumoperitoneum)

- Additional laboratory changes (metabolic and respiratory acidosis, disseminated intravascular coagulation)

Ultrasonography has proven to be useful as it may detect signs and complications of NEC before they are evident on radiographs, specifically in cases that involve a paucity of bowel gas, a gasless abdomen, or a sentinel loop.[8] Diagnosis is ultimately made in 5–10% of very low-birth-weight infants (<1,500g).[9]

Alimentary tract of infant showing intestinal necrosis, pneumatosis intestinalis, and perforation site (arrow). Autopsy.

Alimentary tract of infant showing intestinal necrosis, pneumatosis intestinalis, and perforation site (arrow). Autopsy. Closeup of intestine of infant showing necrosis and pneumatosis intestinalis. Autopsy.

Closeup of intestine of infant showing necrosis and pneumatosis intestinalis. Autopsy. Gross pathology of neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Autopsy of infant showing abdominal distension, intestinal necrosis and hemorrhage, and peritonitis due to perforation.

Gross pathology of neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Autopsy of infant showing abdominal distension, intestinal necrosis and hemorrhage, and peritonitis due to perforation.

Prevention

Prevention includes the use of breast milk and probiotics.[2] A 2012 policy by the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended feeding preterm infants human milk, finding "significant short- and long-term beneficial effects," including reducing the rate of NEC by a factor of two or more.[10]

Small amounts of oral feeds of human milk starting as soon as possible, while the infant is being primarily fed intravenously, primes the immature gut to mature and become ready to receive greater intake by mouth.[11] Human milk from a milk bank or donor can be used if mother's milk is unavailable. The gut mucosal cells do not get enough nourishment from arterial blood supply to stay healthy, especially in very premature infants, where the blood supply is limited due to immature development of the capillaries, so nutrients from the lumen of the gut are needed.

Towards understanding intervention with human milk, experts have noted cow and human milk differ in their immunoglobular and glycan compositions.[12][13] Due to their relative ease of production, human milk oligosaccharides (HMO) are a subject of particular interest in supplementation and intervention.[14]

A Cochrane review in 2014 found that supplementation of probiotics enterally "prevents severe NEC as well as all-cause mortality in preterm infants."[15]

Advancing enteral feed volumes at lower rates does not appear to reduce the risk of NEC or death in very preterm infants.[16] Not beginning feeding an infant by mouth for more than 4 days does not appear to have protective benefits.[17]

Treatment

Treatment consists primarily of supportive care including providing bowel rest by stopping enteral feeds, gastric decompression with intermittent suction, fluid repletion to correct electrolyte abnormalities and third-space losses, support for blood pressure, parenteral nutrition,[18] and prompt antibiotic therapy.

Monitoring is clinical, although serial supine and left lateral decubitus abdominal X-rays should be performed every six hours.

As an infant recovers from NEC, feeds are gradually introduced. "Trophic feeds" or low-volume feeds (<20 ml/kg/day) are usually initiated first. How and what to feed are determined by the extent of bowel involved, the need for surgical intervention and the infant's clinical appearance.[19]

Where the disease is not halted through medical treatment alone, or when the bowel perforates, immediate emergency surgery to resect the dead bowel is generally required, although abdominal drains may be placed in very unstable infants as a temporizing measure. Surgery may require a colostomy, which may be able to be reversed at a later time. Some children may suffer from short bowel syndrome if extensive portions of the bowel had to be removed.

In the case of an infant whose bowel is left in discontinuity, the surgical creation of a mucous fistula or connection to the distal bowel may be helpful as this allows for re-feeding of ostomy output to the distal bowel. This re-feeding process is believed to improve bowel adaptation and aid in advancement of feeds.[19]

Prognosis

Typical recovery from NEC if medical, non-surgical treatment succeeds, includes 10–14 days or more without oral intake and then demonstrated ability to resume feedings and gain weight. Recovery from NEC alone may be compromised by co-morbid conditions that frequently accompany prematurity. Long-term complications of medical NEC include bowel obstruction and anemia.

In the United States of America it caused 355 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2013, down from 484 per 100,000 live births in 2009. Rates of death were almost three times higher for the black populations than for the white populations.[20]

Overall, about 70-80% of infants who develop NEC survive.[21] Medical management of NEC shows an increased chance of survival compared to surgical management.[21] Despite a significant mortality risk, long-term prognosis for infants undergoing NEC surgery is improving, with survival rates of 70–80%. "Surgical NEC" survivors are at risk for complications including short bowel syndrome and neurodevelopmental disability.

References

- "Necrotizing Enterocolitis – Pediatrics – Merck Manuals Professional Edition". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. February 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- Rich, BS; Dolgin, SE (December 2017). "Necrotizing Enterocolitis". Pediatrics in Review. 38 (12): 552–559. doi:10.1542/pir.2017-0002. PMID 29196510. S2CID 39251333.

- Crocetti, Michael; Barone, Michael A.; Oski, Frank A. (2004). Oski's Essential Pediatrics. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 59. ISBN 9780781737708.

- Panigrahi, P (2006). "Necrotizing enterocolitis: a practical guide to its prevention and management". Paediatric Drugs. 8 (3): 151–65. doi:10.2165/00148581-200608030-00002. PMID 16774295. S2CID 29437889.

- Yee, Wendy H.; Soraisham, Amuchou Singh; Shah, Vibhuti S.; Aziz, Khalid; Yoon, Woojin; Lee, Shoo K.; Canadian Neonatal Network (1 February 2012). "Incidence and Timing of Presentation of Necrotizing Enterocolitis in Preterm Infants". Pediatrics. 129 (2): e298–e304. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2022. PMID 22271701. S2CID 26079047. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- Lin PW, Stoll BJ. Necrotising enterocolitis. Lancet. 2006 Oct 7;368(9543):1271–83.

- Schanler, R.J. (2016). "Clinical features and diagnosis of necrotizing enterocolitis in newborns". UpToDate.

- Muchantef K, Epelman M, Darge K, Kirpalani H, Laje P, Anupindi SA. Sonographic and radiographic imaging features of the neonate with necrotizing enterocolitis: correlating findings with outcomes. Pediatr Radiol. 2013 Jun 15.

- Marino, Bradley S.; Fine, Katie S. (1 December 2008). Blueprints Pediatrics. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-8251-7.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Section on Breastfeeding (2012). "Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk". Pediatrics. 129 (3): e827–e841. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-3552. PMID 22371471. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

Meta-analyses of 4 randomized clinical trials performed over the period 1983 to 2005 support the conclusion that feeding preterm infants human milk is associated with a significant reduction (58%) in the incidence of NEC. A more recent study of preterm infants fed an exclusive human milk diet compared with those fed human milk supplemented with cow-milk-based infant formula products noted a 77% reduction in NEC.

- Ziegler EE, Carlson SJ (March 2009). "Early nutrition of very low birth weight infants". J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 22 (3): 191–7. doi:10.1080/14767050802630169. PMID 19330702. S2CID 36737314.

- Bode, L. (2012-04-18). "Human milk oligosaccharides: Every baby needs a sugar mama". Glycobiology. 22 (9): 1147–1162. doi:10.1093/glycob/cws074. ISSN 0959-6658. PMC 3406618. PMID 22513036.

- Boix-Amorós, Alba; Collado, Maria Carmen; Van’t Land, Belinda; Calvert, Anna; Le Doare, Kirsty; Garssen, Johan; Hanna, Heather; Khaleva, Ekaterina; Peroni, Diego G; Geddes, Donna T; Kozyrskyj, Anita L (2019-05-21). "Reviewing the evidence on breast milk composition and immunological outcomes". Nutrition Reviews. 77 (8): 541–556. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuz019. ISSN 0029-6643. PMID 31111150.

- Bode, Lars; Contractor, Nikhat; Barile, Daniela; Pohl, Nicola; Prudden, Anthony R.; Boons, Geert-Jan; Jin, Yong-Su; Jennewein, Stefan (2016-09-15). "Overcoming the limited availability of human milk oligosaccharides: challenges and opportunities for research and application". Nutrition Reviews. 74 (10): 635–644. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuw025. ISSN 0029-6643. PMC 6281035. PMID 27634978.

- AlFaleh K, Anabrees J (2014). "Probiotics for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD005496. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005496.pub4. PMID 24723255.

- Oddie, Sam J.; Young, Lauren; McGuire, William (30 August 2017). "Slow advancement of enteral feed volumes to prevent necrotising enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8: CD001241. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001241.pub7. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6483766. PMID 28854319.

- Morgan, J; Young, L; McGuire, W (1 December 2014). "Delayed introduction of progressive enteral feeds to prevent necrotising enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD001970. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001970.pub5. PMC 7063979. PMID 25436902.

- Heird, WC; Gomez, MR (June 1994). "Total parenteral nutrition in necrotizing enterocolitis". Clinics in Perinatology. 21 (2): 389–409. doi:10.1016/s0095-5108(18)30352-x. PMID 8070233.

- Christian, Vikram J.; Polzin, Elizabeth; Welak, Scott (August 2018). "Nutrition Management of Necrotizing Enterocolitis". Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 33 (4): 476–482. doi:10.1002/ncp.10115. PMID 29940075. S2CID 49419886.

- Xu, Jiaquan; Sherry L. Murphy; Kenneth D. Kochanek; Brigham A. Bastian (February 2016). "Deaths: Final Data for 2013" (PDF). National Vital Statistics Reports. 64 (2): 97. PMID 26905861. Retrieved May 26, 2016.

- Schanler, R.J. (2017). "Management of necrotizing enterocolitis in newborns". UpToDate.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |