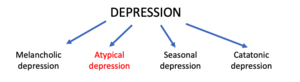

Atypical depression

Atypical depression as it has been known in the DSM IV, is depression that shares many of the typical symptoms of the psychiatric syndromes of major depression or dysthymia but is characterized by improved mood in response to positive events. In contrast to atypical depression, people with melancholic depression generally do not experience an improved mood in response to normally pleasurable events. Atypical depression also features significant weight gain or an increased appetite, hypersomnia, a heavy sensation in the limbs, and interpersonal rejection sensitivity that results in significant social or occupational impairment.[4]

| Atypical depression | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Depression with atypical features |

| |

| Depression subtypes | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

| Symptoms | Low mood, mood reactivity, hyperphagia, hypersomnia, leaden paralysis, interpersonal rejection sensitivity |

| Complications | Suicide |

| Usual onset | Typically adolescence[1] |

| Types | Primary anxious, primarily vegetative[1] |

| Risk factors | Bipolar disorder, anxiety disorder, female sex[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Melancholic depression, anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder |

| Frequency | 15-29% of depressed patients[3] |

Despite its name, "atypical" depression does not mean it is uncommon or unusual.[5] The reason for its name is twofold: (1) it was identified with its "unique" symptoms subsequent to the identification of melancholic depression and (2) its responses to the two different classes of antidepressants that were available at the time were different from melancholic depression (i.e., MAOIs had clinically significant benefits for atypical depression, while tricyclics did not).[6]

Atypical depression is four times more common in females than in males.[7] Individuals with atypical features tend to report an earlier age of onset (e.g. while in high school) of their depressive episodes, which also tend to be more chronic[8] and only have partial remission between episodes. Younger individuals may be more likely to have atypical features, whereas older individuals may more often have episodes with melancholic features.[4] Atypical depression has high comorbidity of anxiety disorders, carries more risk of suicidal behavior, and has distinct personality psychopathology and biological traits.[8] Atypical depression is more common in individuals with bipolar I,[8] bipolar II,[8][9] cyclothymia[8] and seasonal affective disorder.[4] Depressive episodes in bipolar disorder tend to have atypical features,[8] as does depression with seasonal patterns.[10]

Pathophysiology

Significant overlap between atypical and other forms of depression have been observed, though studies suggest there are differentiating factors within the various pathophysiological models of depression. In the endocrine model, evidence suggests the HPA axis is hyperactive in melancholic depression, and hypoactive in atypical depression. Atypical depression can be differentiated from melancholic depression via verbal fluency tests and psychomotor speed tests. Although both show impairment in several areas such as visuospatial memory and verbal fluency, melancholic patients tend to show more impairment than atypical depressed patients.[11]

Furthermore, regarding the inflammatory theory of depression, inflammatory blood markers (cytokines) appear to be more elevated in atypical depression when compared to non-atypical depression.[12]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of atypical depression is based on the criteria stated in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). DSM-5 defines Atypical Depression as a subtype of major depressive disorder that presents with atypical features, characterized by:

- Mood reactivity (i.e., mood brightens in response to actual or potential positive events)

- At least two of the following:

- Significant weight gain or increase in appetite (hyperphagia);

- Hypersomnia (sleeping too much, as opposed to the insomnia present in melancholic depression);

- Leaden paralysis (i.e., heavy feeling resulting in difficulty moving the arms or legs);

- Long-standing pattern of interpersonal rejection sensitivity (not limited to episodes of mood disturbance) that results in significant social or occupational impairment.

- Criteria are not met for With Melancholic Features or With Catatonic Features during the same episode.

Treatment

Due to the differences in clinical presentation between atypical depression and melancholic depression, studies were conducted in the 1980s and 1990s to assess the therapeutic responsiveness of the available antidepressant pharmacotherapy in this subset of patients.[13] Currently, antidepressants such as SSRIs, SNRIs, NRIs, and mirtazapine are considered the best medications to treat atypical depression due to efficacy and fewer side effects than previous treatments.[14] Bupropion, a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, may be uniquely suited to treat the atypical depression symptoms of lethargy and increased appetite in adults.[14]

Before the year 2000, Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) were shown to be of superior efficacy compared to other antidepressants for the treatment of atypical depression, and were used as first-line treatment for atypical depression. Regardless of the demonstrated superiority, treatment with MAOIs requires avoidance of tyramine-containing foods (aged cheese, wine, fava beans) and have many undesirable adverse effects such as hypertensive crisis.[13] Hypertensive crisis is a state of extremely high blood pressure and present with symptoms such as sweating, palpitations, chest pain, shortness of breath.[15] For these reasons, MAOIs are rarely used as the preferred agent in the setting of atypical depression. There is also a newer, selective and reversible MAOI Moclobemide, which doesn't require tyramine diet and has less side effects.

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) were also used prior to the year 2000 for atypical depression, but were not as efficacious as MAOIs, and have fallen out of favor with prescribers due to the less tolerable side effects of TCAs and more adequate therapies being available.[13]

Some evidence supports that psychotherapy such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has equal efficacy to MAOI.[16] These are talk therapy sessions with psychiatrists to help the individual identify troubling thoughts or experiences that may have affected their mental state, and corresponding develop coping mechanisms for each identified issue.[17]

No robust guidelines for the treatment of atypical depression currently exist.[18]

Epidemiology

True prevalence of atypical depression is difficult to determine. Several studies conducted in patients diagnosed with a depressive disorder show that about 40% exhibit atypical symptoms, with four times more instances found in female patients.[19] Research also supports that atypical depression tends to have an earlier onset, with teenagers and young adults more likely to exhibit atypical depression than older patients.[20] Patients with atypical depression have shown to have higher rates of neglect and abuse in their childhood as well as alcohol and drug disorders in their family.[11] Overall, rejection sensitivity is the most common symptom, and due to some studies forgoing this criterion, there is concern for underestimation of prevalence.[21]

Research

In general, atypical depression tends to cause greater functional impairment than other forms of depression. Atypical depression is a chronic syndrome that tends to begin earlier in life than other forms of depression—usually beginning in the teenage years. Similarly, patients with atypical depression are more likely to suffer from personality disorders and anxiety disorders such as borderline personality disorder, avoidant personality disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and bipolar disorder.[4]

Recent research suggests that young people are more likely to suffer from hypersomnia while older people are more likely to suffer from polyphagia.[22]

Medication response differs between chronic atypical depression and acute melancholic depression. Some studies suggest that the older class of antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), may be more effective at treating atypical depression.[23] While the more modern SSRIs and SNRIs are usually quite effective in this illness, the tricyclic antidepressants typically are not.[4] The wakefulness-promoting agent modafinil has shown considerable effect in combating atypical depression, maintaining this effect even after discontinuation of treatment.[24] Antidepressant response can often be enhanced with supplemental medications, such as buspirone, bupropion, or aripiprazole. Psychotherapy, whether alone or in combination with medication, is also an effective treatment.

References

- Davidson JR; Miller RD; Turnbull CD; Sullivan JL (1982). "Atypical depression". Arch Gen Psychiatry. 39 (5): 527–34. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290050015005. PMID 7092486.

- Singh T, Williams K (2006). "Atypical depression". Psychiatry (Edgmont). 3 (4): 33–9. PMC 2990566. PMID 21103169.

- Thase ME (2007). "Recognition and diagnosis of atypical depression". J Clin Psychiatry. 68 Suppl 8: 11–6. PMID 17640153.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Mood Disorders. In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., text rev.) Washington, DC: Author.

- "Atypical depression". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2013-06-23.

- Cristancho, Mario (2012-11-20). "Atypical Depression in the 21st Century: Diagnostic and Treatment Issues". Psychiatric Times. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- Dorota Łojko, et. al (2017). "Atypical depression: current perspectives, Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment

- Singh T, Williams K (2006). "Atypical depression". Psychiatry. 3 (4): 33–9. PMC 2990566. PMID 21103169.

- Perugi G, Akiskal HS, Lattanzi L, Cecconi D, Mastrocinque C, Patronelli A, Vignoli S, Bemi E (1998). "The high prevalence of 'soft' bipolar (II) features in atypical depression". Comprehensive Psychiatry. 39 (2): 63–71. doi:10.1016/S0010-440X(98)90080-3. PMID 9515190.

- Juruena MF, Cleare AJ (2007). "Superposição entre depressão atípica, doença afetiva sazonal e síndrome da fadiga crônica" [Overlap between atypical depression, seasonal affective disorder and chronic fatigue syndrome]. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria (in Portuguese). 29 Suppl 1: S19–26. doi:10.1590/S1516-44462007000500005. PMID 17546343.

- Bosaipo, Nayanne Beckmann; Foss, Maria Paula; Young, Allan H.; Juruena, Mario Francisco (2017-02-01). "Neuropsychological changes in melancholic and atypical depression: A systematic review". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 73: 309–325. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.12.014. ISSN 0149-7634. PMID 28027956.

- Łojko D, Rybakowski JK (2017). "Atypical depression: current perspectives". Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 13: 2447–2456. doi:10.2147/NDT.S147317. PMC 5614762. PMID 29033570.

- Stewart, Jonathan W.; Thase, Michael E. (2007-04-15). "Treating DSM-IV Depression With Atypical Features". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 68 (4): e10. doi:10.4088/jcp.0407e10. ISSN 0160-6689. PMID 17474800.

- "Clinical Practice Review for Major Depressive Disorder | Anxiety and Depression Association of America, ADAA". adaa.org. Retrieved 2019-11-22.

- "mao_pharmacology [TUSOM | Pharmwiki]". tmedweb.tulane.edu. Retrieved 2019-11-20.

- Mercier, MA (1992). "A pilot sequential study of cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy of atypical depression". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 53 (5): 166–70. PMID 1592844.

- "What is Psychotherapy?". www.psychiatry.org. Retrieved 2019-11-21.

- Łojko, Dorota (2017). "Atypical depression: current perspectives". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 13: 2447–2456. doi:10.2147/NDT.S147317. PMC 5614762. PMID 29033570.

- Dorota Łojko, et. al (2017). "Atypical depression: current perspectives, Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment

- Tanvir Singh et. al (2006). "Atypical depression, Psychiatry (Edgmont).

- Quitkin FM (2002). "Depression With Atypical Features: Diagnostic Validity, Prevalence, and Treatment". Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 4 (3): 94–99. doi:10.4088/pcc.v04n0302. PMC 181236. PMID 15014736.

- Posternak MA, Zimmerman M (2001). "Symptoms of atypical depression". Psychiatry Research. 104 (2): 175–81. doi:10.1016/S0165-1781(01)00301-8. PMID 11711170.

- "Atypical depression - Symptoms and Causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Vaishnavi S, Gadde K, Alamy S, Zhang W, Connor K, Davidson JR (2006). "Modafinil for atypical depression: effects of open-label and double-blind discontinuation treatment". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 26 (4): 373–8. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000227700.263.75.39. PMID 16855454.

External links

- Stewart JW, Quitkin FM, McGrath PJ, Klein DF (2005). "Defining the boundaries of atypical depression: evidence from the HPA axis supports course of illness distinctions". Journal of Affective Disorders. 86 (2–3): 161–7. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2005.01.009. PMID 15935235.

- Atypical Depression - Depression Central Mood Disorders & Treatment, Satish Reddy, MD., Editor (Formerly Dr. Ivan Goldberg's Depression Central)

| Classification |

|---|