Wroxeter

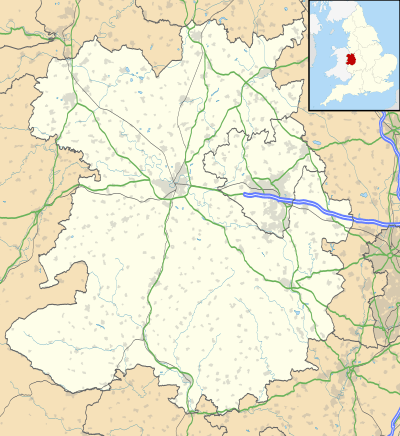

Wroxeter /ˈrɒksɪtər/ is a village in Shropshire, England, which forms part of the civil parish of Wroxeter and Uppington, beside the River Severn, 5 miles (8.0 km) south-east of Shrewsbury.

Viroconium Cornoviorum, the fourth largest city in Roman Britain, was sited here, and is gradually being excavated.

History

Roman Wroxeter, near the end of the Watling Street Roman road that ran across England from Dubris (Dover), was a key frontier position lying on the bank of the Severn river whose valley penetrated deep into Wales, and also on a route to the south leading to the Wye valley.

Archaeology has shown that the site of the later city first was established about AD 55 as a frontier post for a Thracian legionary cohort located at a fort near the Severn river crossing.[1] A few years later a legionary fortress (castrum) was built within the site of the later city for the Legio XIV Gemina during their invasion of Wales.

The local British tribe of the Cornovii had their original capital (also thought to have been named *Uiroconion) at the hillfort on the Wrekin. When the Cornovii were eventually subdued their capital was moved to Wroxeter and given its Roman name.

This legion XIV Gemina was later replaced by the Legio XX Valeria Victrix which in turn relocated to Chester around AD 88. As the military abandoned the fortress the site was taken over by the Cornovians' civilian settlement.

The name of the settlement, meaning "Viroconium of the Cornovians", preserves a native Brittonic name that has been reconstructed as *Uiroconion ("[the city] of *Uirokū"), where *Uiro-ku (lit. "man"-"wolf") is believed to have been a masculine given name meaning "werewolf".[2][3]

Viroconium prospered over the next century, with the construction of many public buildings, including thermae and a colonnaded forum. At its peak, it is thought to have been the 4th-largest settlement in Roman Britain, with a population of more than 15,000.[4]

The Roman city is first documented in Ptolemy's 2nd century Geography as one of the cities of the Cornovii tribe, along with Chester (Deva Victrix).

Following the Roman withdrawal from Britain around AD 410, the Cornovians seem to have divided into Pengwern and Powys. The minor Magonsæte sub-kingdom also emerged in the area in the interlude between Powysian and Mercian rule. Viroconium may have served as the early post-Roman capital of Powys prior to its removal to Mathrafal sometime before 717, following famine and plague in the area. The city has been variously identified with the Cair Urnarc[5] and Cair Guricon[6] which appeared in the 9th-century History of the Britons's list of the 28 cities of Britain.[7]

N. J. Higham proposes that Wroxeter became the eponymous capital of an early sub-Roman kingdom known as the Wrocensaete, which he asserts was the successor territorial unit to Cornovia. The literal meaning of Wrocensaete is 'those dwelling at Wrocen', which Higham interprets as Wroxeter. It may refer quite specifically to the royal court itself, in the first instance, and only by extension to the territory administered from the court.[8]

The Roman city was rediscovered in 1859 when workmen began excavating the baths complex.[9][13] A replica Roman villa was constructed in 2010 for a Channel 4 television programme called Rome Wasn't Built in a Day and was opened to the public on 19 February 2011.[14]

St Andrew's

At the centre of Wroxeter village is Saint Andrew's parish church, some of which is built from re-used Roman masonry. The oldest visible section of the church is the Anglo-Saxon part of the north wall which is built of Roman monumental stone blocks. The chancel and the lower part of the tower are Norman.[15] The gatepiers to the churchyard are a pair of Roman columns and the font in the church was made by hollowing out the capital of a Roman column.[16] Later additions to the church incorporate remains of an Anglo-Saxon preaching cross and carvings salvaged from nearby Haughmond Abbey following the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

The west window, bearing figures of St Andrew and St George, designed by the workshops of Morris & Co., is a parish war memorial, as is a brass plaque listing parish men who died serving in World War I, one of whom, Captain C.W. Wolseley-Jenkins, has an individual memorial plaque in the east end.[17]

St. Andrew's was declared redundant in 1980 and is now managed by The Churches Conservation Trust. St. Andrew's parish is now united with that of St. Mary, Eaton Constantine.[18]

Literary reference

A. E. Housman visited the site and was impressed enough to write of "when Uricon the city stood", the poem ending "Today the Roman and his trouble Are ashes under Uricon."[19]

Bernard Cornwell has the main character of The Saxon Stories visit Wroxeter in Death of Kings, referring to it as an ancient Roman city that was "as big as London" and using it as an illustration of his pagan beliefs that the World will end in chaos.[20]

Sport

The village previously had a football team, Wroxeter Rovers FC. In 2017, the club was renamed to "Shrewsbury Juniors FC", in order to provide a senior football team for kids progressing through the club's junior football system to take part in after the age of 16-17. The club currently compete in the Shropshire Premier League.

References

- Rome Against Caractacus, G. Webster. ISBN 0713472545, pp. 49–53

- Delamarre, Xavier (2012). Noms de lieux celtiques de l'europe ancienne. Arles: Editions Errance. p. 273. ISBN 978-2-87772-483-8.

- Wodtko, Dagmar (2000). Wörterbuch der keltiberischen Inschriften: Monumenta Linguarum Hispanicarum, Band V.1. Reichert-Verlag. p. 452. ISBN 978-3-89500-136-9.

- Frere, S. S. Britannia: a History of Roman Britain. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., 1987. ISBN 0-7102-1215-1.

- Newman, John Henry & al. Lives of the English Saints: St. German, Bishop of Auxerre, Ch. X: "Britain in 429, A. D.", p. 92. James Toovey (London), 1844.

- Ford, David Nash. "The 28 Cities of Britain" at Britannia. 2000.

- Nennius (attrib.). Theodor Mommsen (ed.). Historia Brittonum, VI. Composed after AD 830. (in Latin) Hosted at Latin Wikisource.

- Higham, Nick J. (1993). The Origins of Cheshire. Manchester University Press. pp. 68–77. ISBN 0-7190-3160-5.

- English Heritage: Wroxeter Roman City

- Barker, P., Bird, H., Corbishley, M., Pretty, K., White, R. (1997) The Baths Basilica Wroxeter Excavations: 1966–90. English Heritage

- Chadderton, J., Webster, G. (2002) The Legionary Fortress at Wroxeter: Excavations by Graham Webster, 1955–85. English Heritage

- Ellis, P. (2000) The Roman Baths and Macellum at Wroxeter Excavations 1955–85. English Heritage

- English Heritage has recently published a series of monographs on the excavations at Wroxeter from the 1950s to 1990s[10][11][12] These are available through the Archaeology Data Service.

- BBC News Reconstructed Roman villa unveiled at Wroxeter

- Pevsner, Nicholas, Shropshire, 1958, p. 327

- Aston & Bond, 1976, page 53

- Francis, Peter (2013). Shropshire War Memorials, Sites of Remembrance. YouCaxton Publications. pp. 124–125. ISBN 978-1-909644-11-3.

- Archbishops' Council (2010). "Eaton Constantine S.Mary, Eaton Constantine". A Church Near You. Church of England. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- A. E. Housman, A Shropshire Lad, poem XXXI, 1896

- Bernard Cornwell, Death of Kings, Part Two – "Angels", 2012

Further reading

- Aston, Michael; Bond, James (1976). The Landscape of Towns. Archaeology in the Field Series. London: J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd. pp. 45–48, 51–54. ISBN 0-460-04194-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wroxeter. |