Leicester and Swannington Railway

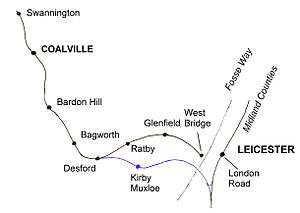

The Leicester and Swannington Railway (L&S) was one of England's first railways, being opened on 17 July 1832 to bring coal from collieries in west Leicestershire to Leicester.

Overview

The construction of the railway was a pivotal moment in the transport history of East Midlands, which was characterised by fierce rivalry between the coalmasters of Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire. Through the latter half of the eighteenth century, the Leicestershire miners, using horses and carts, had been at a disadvantage compared to those in Nottinghamshire, who had access to the Erewash Canal and the Soar Navigation. In 1794 the latter was extended to Leicester. A branch – the Charnwood Forest Canal – opened up the Leicester trade but, in 1799, part of it collapsed, closing it.

In 1828 William Stenson observed the success of the Stockton and Darlington Railway and, with John Ellis, and his son Robert, travelled to see George Stephenson where he was building the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Stephenson visited Leicester on their invitation and agreed to become involved. The first meeting to discuss the line was held at the Bell Inn in Leicester, where subscriptions amounting to £58,250 were raised. The remainder of the £90,000 was raised through Stephenson's financial contacts in Liverpool. The line obtained the Royal Assent in 1830 and the first part opened in 1832.[1]

The line was only the fifth such line to be authorised, opening six years before the London and Birmingham, and required techniques, particularly for the tunnel, that were then virtually untried. Its success led to the initial moves by the Nottinghamshire miners towards a rail connection from the Mansfield and Pinxton Railway down the Erewash Valley which eventually became the Midland Counties Railway.

Construction

The engineer for the railway was Robert Stephenson, with the assistance of Thomas Miles, while his father raised much of the capital for the line from friends in Liverpool.

Like other early railways, it followed canal practice in that it consisted of essentially level sections linked by inclines (taking the place of the canal's locks), where the trains were drawn up and lowered down by rope. Even so, it featured some quite heavy earthworks. From a station and coal wharf alongside the Soar Navigation at West Bridge on the west side of the Fosse Way in Leicester, it headed northwards for about a mile, before passing through the 1,796 yards (1,642 m) long tunnel at Glenfield, to the valley of the Rothley Brook. It proceeded about five miles to Desford, then swung north west towards Bagworth.

The original Bagworth station was at the foot of a 1 in 29 self-acting inclined plane to the summit at 565 feet (172 m). Then the line passed through a cutting at Battleflat before reaching Bardon Hill and on to Long Lane where new collieries were opened. Beyond Long Lane the railway descended by a further inclined plane of 1 in 17 to the existing coal mines at Swannington and an end on connection with the Coleorton Tramway, which linked to further coal mines and limestone quarries. The track was to be single throughout.

Construction began almost immediately, but soon ran into trouble, particularly with the tunnel. Initial boring had suggested that it would not need a lining. However, it turned out that some 500 yards (460 m) would be through porous sandstone. During its construction in 1831 the contractor, Daniel Jowett, fell down a working shaft and was killed.

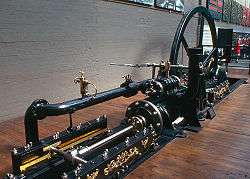

The low power of contemporary steam engines meant that where the gradient was steepest, locomotive haulage gave way to other means. As was common in those days, "There were two inclines on the line: one at Bagworth, rising at 1 in 29 towards Swannington and worked by gravity; and a much steeper though shorter one at the Swannington end, descending at 1 in 17 and worked by stationary engine ..."[2] The latter was built by the Horsely Coal and Iron Company, and was equipped with a very early example of a piston valve.[1]

Early operation

The first part of the line opened on 17 July 1832 with a train hauled by Comet, driven by George Stephenson himself, with driver Weatherburn, from Leicester to the first Bagworth station at the foot of Bagworth incline.[1] The locomotive's 13 feet (4 m) high chimney was knocked down by Glenfield Tunnel, due to the track having been packed up too high. It is said that the train stopped so that the passengers could wash themselves in the nearby Rothley Brook.

Difficulties remained with the cutting at Battleflat and the remainder of the line to Swannington did not open until 1833.

By the end of 1833 the line was delivering coal from Whitwick, Ibstock and Bagworth collieries far more cheaply than could be done from the Erewash Valley.

The expansion of the coal trade transformed the area, even giving rise to a new town at Long Lane - Coalville. George Stephenson himself settled at Ravenstone, near Ashby-de-la-Zouch and, with his son Robert, opened a colliery at Snibston in 1833. He was commemorated by the inclusion of the red fleur de lys in the arms of the former Ashby de la Zouch Rural District Council.

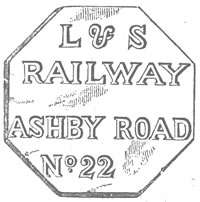

The usual train consisted of twenty-four wagons of 32 cwt each. The idea that there would be a demand from passengers came a something of a surprise to the directors, but a carriage was hastily built, and very soon the line was carrying about 60 passengers a day and their fares were repaying one per cent of the capital. In time, both first and second class was provided. On payment of the fare at the departure station, each passenger would receive a metal token marked with the destination. This would be given up on arrival and reused. Small four-wheeled wagons and coaches, painted plain blue, comprised the rolling stock.[1]

For many years facilities for passengers remained primitive, with local inns and tiny cabins serving as booking offices and passenger carriages being attached to goods trains. There was no platform at West Bridge until a new passenger station was opened there in 1839 to handle the passenger trains that had been introduced six years earlier.[3]

Glenfield tunnel was only the second tunnel in the World on a passenger railway, having shortly followed the opening of one on the Canterbury and Whitstable Railway. It proved an attraction for the inquisitive and had to be fitted with gates.[4]

Meanwhile, devastated by the loss of their Leicester trade, the Erewash coalmasters met at the George Inn at Alfreton and decided to build their own line to Leicester, down the Erewash Valley from the Mansfield and Pinxton Railway, a tramway which had been built in 1819. Though not completed along its full length until much later, this was the beginning of the Midland Counties Railway, which in turn, became a founding partner in the Midland Railway.

Locomotives

Five locomotives were built by Robert Stephenson and Company for the line. The first was Comet, shipped from the works by sea to Hull and thence by canal, its first trip being on the opening day in 1832, when it is alleged its 13-foot high chimney was knocked down by Glenfield Tunnel. The second engine, Phoenix, was delivered in 1832; both had four-coupled wheels. Phoenix was sold in 1835 to work in the construction of the London and Birmingham Railway. The next were Samson and Goliath, delivered in 1833. They were initially four-coupled, but were extremely unstable and a pair of trailing wheels were added. This 0-4-2 formation was also used for Hercules, the next engine to enter service. These were the first six-wheeled goods engines with inside cylinders and, after the flanges were taken off the centre pairs of wheels, were so satisfactory, that Stephenson decided never to build another four-wheeled engine.

Whistle

According to Clement Stretton,[5] on almost its first run, at Thornton crossing, Samson collided with a horse and cart on its way to Leicester Market with a load of butter and eggs. Although the engine had a horn, it clearly was not loud enough, and at the suggestion of Mr. Bagster, the manager, the engines were provided with the first steam whistles.

However, in C. R. Clinker's account of the Leicester and Swannington Railway it states that the Minutes of Directors' meetings record accidents, some trivial. There is no reference to this collision in the Minutes, nor to any payments made for claims for damages or to a "musical instrument maker". Trade directories of Leicester for the time do not include an instrument maker in King Street.[1]

0-6-0 Design

By 1834, traffic had increased to such an extent that more powerful engines were needed and the next to be delivered was Atlas, the first ever six-coupled 0-6-0 inside cylinder design. Although inside cylinders were more difficult to build and maintain, and, in the early days, prone to breakage of the crank axles, the engines were more stable than their outside cylindered counterparts. The design was so successful that it was the basic pattern for many goods engines over the next hundred years. The cramped space between the wheels, was a factor in the choice of a wider gauge in some railways overseas.

So far all the engines had been provided by Stephenson, but the directors decided to try one of Edward Bury's locomotives. Stephenson was, of course, extremely influential in the running of the line, but agreed provided the Bury engine was tested fairly. Accordingly, the Liverpool arrived in 1834. An 0-4-0, it proved unequal to the loads hauled by Atlas. The next engine bought for the line was Vulcan, an 0-6-0 by Tayleur and Company. The last two were by the Haigh Foundry, Ajax, 0-4-2 and Hector, 0-6-0. This last engine was so powerful that it became the pattern for engines built for the Manchester and Leeds Railway, the North Midland Railway, the Great Western Railway and the Liverpool and Manchester Railway.

Takeover

| Leicester– Burton upon Trent line | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Coal and quarry traffic made the line profitable, but with increasing competition, various schemes were afoot, including incorporation into the Trent Valley line with a branch from Atherstone and Polesworth via Market Bosworth, for which Leicestershire Record Office has deposited plans, as a group of Leicester and Tamworth financiers had expressed an interest in buying the line. However, in August 1845 the directors sold out to the Midland Railway, which lost no time in improving the line.

Safety concerns prevented passenger trains using the Bagworth Incline. The practice was to provide separate trains for each of the level stretches and passengers would walk between them. A deviation on an easier gradient was therefore built, necessitating the closure of the original Bagworth station at the bottom of the incline and the opening of the new Bagworth and Ellistown station beyond the summit.

Moreover, the intention was to double the line and rather than widen the Glenfield Tunnel a deviation was built from Desford to meet the main line south of Leicester London Road station. The old line to West Bridge would remain mainly as a goods line.

The line was also extended westwards to Burton upon Trent, so transforming the isolated venture into a through route.

This left the Swannington Incline as a branch at one end, and the last few miles to the L&S terminal in Leicester as another.

20th and 21st centuries

Passenger trains on the stub to Leicester (West Bridge) ended in September 1928, although coal and oil traffic continued until 29 April 1966.[6] Since Glenfield tunnel had limited clearance the Midland Railway built a batch of 6-wheel coaches of lower height and 4 inches narrower than normal to work through. They also had bars over their windows so that passengers could not lean out when going through the tunnel.[7]

For enthusiast railtours in later years over the line to West Bridge passengers were carried in brake vans; trains with normal passenger stock had to stop and reverse at Glenfield tunnel. The tunnel also limited the size of locomotives that could work through to West Bridge. In the latter years only Midland Railway Johnson 0-6-0 tender locos worked the trains.

The last three veterans of this class from the late 19th century were retained at Coalville until 1964 specifically for working this line. They were replaced for the last couple of years operation by two BR standard class 2 2-6-0 locomotives which had to be specially adapted by having their cabs cut down to clear the tunnel.[8][9] These were 78013[9] and 78028.[8][9]

The pits at the Swannington end were worked out by as early as 1875, but the incline found a new lease of life lowering wagons of coal to a new pumping station at the foot that kept the old workings clear of water, so preventing flooding in the newer mines nearby. The incline closed in 1948 when electric pumps were installed in the pumping station, but the winding engine was dismantled and is now at the National Railway Museum at York. The site of the incline now belongs to the Swannington Heritage Trust.

Passenger trains on the extended line from Leicester London Road to Burton on Trent ceased in 1964. Despite the end of coal mining in west Leicestershire in the 1980s, which resulted in the end of the coal trains, the railway continues to serve two granite quarries, at Stud Farm near Markfield and Bardon Hill, which produce regular heavy trains. A plan to reopen the line to passenger traffic as a phase of the Ivanhoe Line scheme has so far failed to secure the necessary funds.[10] Some campaigners now refer to the route as the National Forest Line, after the National Forest planted in the area since 1990.

Remains

This is a list of some of the historical remains that can be seen, most of which are on the closed sections of the line.

A short length of platform has been rebuilt on the site of the second passenger station (of 1893) at West Bridge in Leicester, and has track alongside it and a semaphore signal, grid reference SK579044. From here the trackbed is now a public footpath for about a mile towards Glenfield tunnel, to SK569056.

A wooden lifting bridge, based on a design by Robert Stephenson, originally carrying a short branch over the Soar Navigation at West Bridge in Leicester, had been reconstructed next to the entrance of Snibston Discovery Park in Coalville, after spending some years installed on a footpath outside the Abbey Pumping Station in Leicester. However, following the closure of the Discovery Park in July 2015 the bridge has been removed.

A public footpath in Glenfield passes close to the western entrance to Glenfield tunnel, SK544066, which has been bricked up. The eastern entrance to the tunnel has been buried, while the tunnel as a whole was sold to Leicester city council for the nominal sum of £5, though the council has never decided what use to make of it. The tops of several brick ventilator shafts can be seen among the houses of the estate above the tunnel, for example beside the A563 at SK558064; some are in the back gardens of the houses.

The tunnel itself underwent in 2008 a retrofit to install strengthening rings that are hoped to prevent a collapse of the extant tunnel shaft. The £500,000 reinforcement project was commissioned by the Leicester city council and was recorded by the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust and photographed by the Leicestershire Industrial History Society.[11] Occasional "open days" are held for organised groups.[12] From the centre of Glenfield, SK543065, the trackbed has been converted to a public footpath to Ratby, SK518054, where there is a commemorative plaque next to a short length of rail.

Most of the incline at Bagworth, now bypassed by a deviation line, is a public footpath, SK444091 at top to SK453086 near bottom, though its profile has been affected by mining subsidence. Near the top was the bow-fronted incline-keeper's house, SK446091, see photograph near the top of this page. Although this was probably the oldest surviving railway building in the East Midlands,[13] and a grade-two listed building,[14] it was allowed to fall down to become an overgrown pile of bricks after, on a recommendation from English Heritage, the Department of the Environment struck Incline Cottage from the listed building register.[15]

At Coalville the original building for passengers to buy tickets is now a children's nursery beside the level crossing, SK426142.

The incline at Swannington is under the supervision of the Swannington Heritage Trust and the track bed down the incline has been opened as a footpath with information boards. The foundations of the engine house at the top of the incline, SK420156, have been uncovered and about 75 yards (69 m) of track laid have been relaid. The historic winding engine was removed from here after the inclined closed to the National Railway Museum at York.

The central part of the line from Desford to Bardon Hill, on the outskirts of Coalville, is still used daily by the stone trains and can be observed from bridges, level crossings, and footpaths.

Motive power depot

British Railways closed Mantle Lane depot at Coalville in 1990. Its "Category A" status was a clerical error, and was in fact a "Category C". This BR depot was unusual in having no fueling points, fitters or any other shed facilities. Locomotives would be taken in ferries to nearby Bardon or Leicester for refueling, water and sandbox filling. This perhaps shows why it was a surprise to find it as an A listed depot. Little remains at the site which hints at its formerly busy railway past. Two tracks remain where once lay four 'on shed' as it were. The Mantle Lane Sidings are overgrown with saplings that are now more than 20 years old and only a short stretch is usable from the points on the main line before the trees encroach the track.

FM Rail, shortly before its bankruptcy, leased the Mantle Lane Sidings to reduce costs. However, it had not properly assessed the state of the sidings or the work needed to bring them up to spec so only one line was ever used, up to the edge of the trees. Only one tree was ever felled, to allow a wagon to sit a yard or so further in. Following FM's demise, all of its stock at Mantle Lane was taken elsewhere for scrap or further use.

Network Rail recently replaced point mechanisms on the loop and relief lines near to the sidings, which had been out of use for 20 years until FM arrived, and Freightliner now stables its stone wagons here between trips. The former Marcroft Wagon Repair yard is now a wood yard and currently for sale. Viewing on Google Earth shows some clear grooves in the site where rails once ran. All that remains at Mantle Lane is the signalbox, still in use.

Earlier Proposed Railways

The first mention of the term "railway" in a newspaper was in The Times and the Derby Mercury in 1790. At a meeting held in Leicester Castle on 12 July 1790 to discuss making the River Soar navigable to Loughborough, it was also suggested that a cut or a railway from Swannington to Loughborough Basin should be built.[16]

See also

- List of level crossing accidents

References

- Clinker, C.R. (1977) The Leicester & Swannington Railway Bristol: Avon Anglia Publications & Services. Reprinted from the Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological Society Volume XXX, 1954.

- Ellis, C. Hamilton (1953). The Midland Railway. Shepperton: Ian Allan. p. not stated.

- Anderson, P.H. (1973). Forgotten Railways: The East Midlands. The Forgotten Railways Series. Newton Abbott: David & Charles. p. not stated. ISBN 0-7153-6094-9.

- Wilson, B.L. (November 2005). "An Early East Midlands Adventure: Leicester West Bridge to Desford Junction". Railway Bylines: 586–595.

- Stretton, Clement Edwin, The History of the Midland Railway, 1901. pp26-7

- Leleux R. (1976) A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Volume 9 The East Midlands Newton Abbot: David & Charles.

- Hurst J. and Kinder M. (2002) William Bradshaw: Leicester Railway Cameraman 1909 - 1923, The Historical Model Railway Society.

- Gamble H.A. (1989) Railways Around Leicester: Scenes of Times Past Leicester: Anderson Publications.

- (1995) Railway Connections: Steam Days on the Leicester to Burton Line Coalville: Coalville Publishing Co. Ltd.

- "A blow to Ivanhoe hopes". Leicester Mercury. 3 December 2008. Archived from the original on 16 June 2009.

- "Stephenson tunnel saved". The Railway Magazine. Vol. 154 no. 1, 292. December 2008. p. 10.

- Lyne, David. "Dark, dangerous, fascinating and now, accessible". News Letter. Council for British Archaeology (34): 6.

- Palmer, M. (ed.) (1983) Leicestershire Archaeology The Present State of Knowledge: Vol. 3. Industrial Archaeology, Leicester: Leicestershire Museums.

- Palmer, M. (1981) Bagworth Incline Keeper's House, Leicestershire Industrial History Society, LIHS Bulletin 05, September 1981.

- "On This Day: 25 Years Ago". Leicester Mercury. 21 March 2016.

- The Times Thursday, 22 July 1790, p4, Derby Mercury, Thursday 15 July 1790, p4.

Further reading

- Stevenson, P.S. ed, (1989) The Midland Counties Railway, Railway and Canal Historical Society.

- Stretton, John (2005). No 47: Leicestershire. British Railways Past and Present. Kettering: Silver Link Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-85895-198-4.

- Twells, H.N. (1985). A Pictorial Record of the Leicester and Burton Branch Railway. Burton-upon-Trent: Trent Valley Publications. ISBN 0-948131-04-7.

- Twining, A. ed, (1982) An Early Railway: A Car Trail to the Leicester and Swannington Leicester: Leicestershire Museums

- Williams, R. (1988) The Midland Railway: A New History, Newton Abbot: David & Charles

- Whishaw, Francis (1842). The Railways of Great Britain and Ireland Practically Described and Illustrated (2nd ed.). London: John Weale. pp. 184–186. OCLC 833076248.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williams, F.S. (1874) The Midland Railway: Its Rise and Progress Derby: Bemrose and Son

Further listening

- Peter Handford (Dir), (1964) The Glenfield Goods: A journey from Leicester, West Bridge, on a goods train hauled by a Midland 2F class 0-6-0, EAF 78, London: Argo Record Company Limited. An Argo Transacord, 7 inch, 45 rpm, extended play, vinyl recording of 2F 0-6-0 58148, built in 1876, on a train in July 1963. Side 1: between Leicester and Glenfield. Side 2: Shunting at Groby Quarry Sidings, leaving Groby sidings and arriving at Ratby, and the return journey between Ratby and Glenfield.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Leicester and Swannington Railway. |