McDonnell Douglas DC-10

The McDonnell Douglas DC-10 is an American wide-body airliner manufactured by McDonnell Douglas. The DC-10 was intended to succeed the DC-8 for long range flights. It first flew on August 29, 1970; and was introduced on August 5, 1971 by American Airlines.

| DC-10 / MD-10 | |

|---|---|

| |

| A DC-10-30 of Continental Airlines | |

| Role | Wide-body jet airliner |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | McDonnell Douglas |

| First flight | August 29, 1970 |

| Introduction | August 5, 1971 with American Airlines |

| Status | In non-passenger service |

| Primary users | FedEx Express

|

| Produced | 1968–1988 |

| Number built | |

| Unit cost |

US$20M (1972)[2] ($122M today) |

| Variants | |

| Developed into | McDonnell Douglas MD-11 |

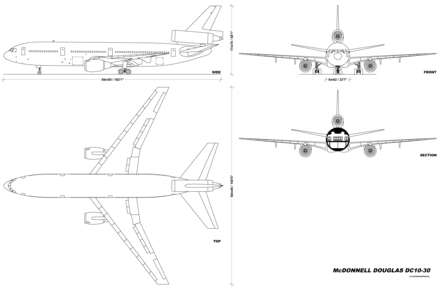

The trijet has two turbofans on underwing pylons and a third one at the base of the vertical stabilizer. The twin aisle layout has a typical seating for 270 in two classes. The initial DC-10-10 had a 3,500 nmi (6,500 km) range for transcontinental flights, and the -15 had more powerful engines for hot and high airports. The -30 and -40 models had higher weights supported by a third main landing gear leg for an intercontinental range of up to 5,200 nmi (9,600 km). Based on the -30, The KC-10 Extender is a U.S. Air Force tanker.

A design flaw in the cargo doors caused a poor safety record in early operations. Following the American Airlines Flight 191 crash (the deadliest US aviation accident), the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) grounded all U.S. DC-10s in June 1979. In August 1983, McDonnell Douglas announced that production would end due to a lack of orders, as it had a widespread public apprehension after the 1979 crash and a poor fuel economy reputation.[3] Design flaws were rectified and fleet hours increased, for a safety record later comparable to similar era passenger jets.

Production ended in 1989, with 386 delivered to airlines along with 60 KC-10 tanker aircraft. The DC-10 outsold the similar Lockheed L-1011 TriStar. It was succeeded by the lengthened, heavier McDonnell Douglas MD-11. After merging with McDonnell Douglas in 1997, Boeing upgraded many in-service DC-10s as the MD-10 with a glass cockpit to eliminate the flight engineer position. In February 2014, the DC-10 made its last commercial passenger flight. Cargo airlines continue to operate it as a freighter, its largest operator is FedEx Express. The Orbis Flying Eye Hospital is a DC-10 adapted for eye surgery. Some DC-10s are on display, while other retired aircraft are in storage.

Development

.jpg)

Following an unsuccessful proposal for the U.S. Air Force's CX-HLS (Heavy Logistics System) in 1965, Douglas Aircraft began design studies based on its CX-HLS design. In 1966, American Airlines offered a specification to manufacturers for a widebody aircraft smaller than the Boeing 747 but capable of flying similar long-range routes from airports with shorter runways. The DC-10 became McDonnell Douglas's first commercial airliner after the merger between McDonnell Aircraft Corporation and Douglas Aircraft Company in 1967.[4] An early DC-10 design proposal was for a four-engine double-deck wide-body jet airliner with a maximum seating capacity of 550 passengers similar in length of a DC-8. The proposal was shelved in favor of a trijet single-deck wide-body airliner with a maximum seating capacity of 399 passengers, and similar in length to the DC-8 Super 60.[5]

On February 19, 1968, in what was supposed to be a knockout blow to the competing Lockheed L-1011, George A. Spater, President of American Airlines, and James S. McDonnell of McDonnell Douglas announced American Airlines' intention to acquire the DC-10. This was a shock to Lockheed and there was general agreement within the U.S. aviation industry that American Airlines had left its competitors at the starting gate. Together with American Airlines' decision to announce the DC-10 order, it was also reported that American Airlines had declared its intention to have the British Rolls-Royce RB211 turbofan engine on its DC-10 aircraft.[6]

The DC-10 was first ordered by launch customers American Airlines with 25 orders, and United Airlines with 30 orders and 30 options in 1968.[7][8] The first DC-10, a series 10, made its maiden flight on August 29, 1970.[9] Following a test program with 929 flights covering 1,551 hours, the DC-10 received its type certificate from the FAA on July 29, 1971.[10] It entered commercial service with American Airlines on August 5, 1971 on a round trip flight between Los Angeles and Chicago, with United Airlines beginning DC-10 flights later that month.[11] American's DC-10s had seating for 206 and United's seated 222; both had six-across seating in first-class and eight-across (four pairs) in coach.[12] The DC-10's similarity to the Lockheed L-1011 in design, passenger capacity, and launch date resulted in a sales competition that affected profitability of the aircraft.

The first DC-10 version was the "domestic" series 10 with a range of 3,800 miles (3,300 nmi, 6,110 km) with a typical passenger load and a range of 2,710 miles (2,350 nmi, 4,360 km) with maximum payload. The series 15 had a typical load range of 4,350 miles (3,780 nmi, 7,000 km).[13][14] The series 20 was powered by Pratt & Whitney JT9D turbofan engines, whereas the series 10 and 30 engines were General Electric CF6. Before delivery of its aircraft, Northwest's president asked that the "series 20" aircraft be redesignated "series 40" because the aircraft was much improved over the original design. The FAA issued the series 40 certificate on October 27, 1972.[15]

The series 30 and 40 were the longer-range "international" versions. The main visible difference between the models is that the series 10 has three sets of landing gear (one front and two main) while the series 30 and 40 have an additional centerline main gear. The center main two-wheel landing gear (which extends from the center of the fuselage) was added to distribute the extra weight and for additional braking. The series 30 had a typical load range of 6,220 mi (10,010 km) and a maximum payload range of 4,604 mi (7,410 km). The series 40 had a typical load range of 5,750 miles (9,265 km) and a maximum payload range of 4,030 miles (3,500 nmi, 6,490 km).[13][16]

The DC-10 had two engine options and introduced longer-range variants a few years after entering service; these allowed it to distinguish itself from its main competitor, the L-1011. The 446th and final DC-10 rolled off the Long Beach, California Products Division production line in December 1988 and was delivered to Nigeria Airways in July 1989.[17][18] The production run exceeded the 1971 estimate of 438 deliveries needed to break even on the project.[19] As the final DC-10s were delivered McDonnell Douglas had started production of its successor, the MD-11.[20]

In the late 1980s, as international travel was growing due to lower oil prices and more economic freedom, widebody demand could not be met by the delayed Boeing 747-400, MD-11 and the Airbus A330/A340 while the B747-200/300 and DC-10 production ended, and the used DC10-30s value nearly doubled from less than $20 million to nearly $40 million.[21]

Design

.jpg)

The DC-10 is a low-wing cantilever monoplane, powered by three turbofan engines. Two engines are mounted on pylons that attach to the bottom of the wings, while the third engine is encased in a protective banjo-shaped structure that is mounted on the top of the rear fuselage. The vertical stabilizer with its two-segment rudder, is mounted on top of the tail engine banjo. The horizontal stabilizer with its four-segment elevator is attached to the sides of the rear fuselage in the conventional manner. The airliner has a retractable tricycle landing gear. To enable higher gross weights, the later -30 and -40 series have an additional two-wheel main landing gear, which retracts into the center of the fuselage.[22]

It was designed for medium to long-range flights that can accommodate 250 to 380 passengers, and is operated by a cockpit flight crew of three. The fuselage has underfloor storage for cargo and baggage.[23]

Variants

Original variants

- DC-10-10

- The DC-10-10 is the initial passenger version introduced in 1971, produced from 1970 to 1981. The DC-10-10 was equipped with GE CF6-6 engines, which was the first civil engine version from the CF6 family. A total of 122 were built.[24]

- DC-10-10CF

- The -10CF is a convertible passenger and cargo transport version of the -10. Eight were built for Continental Airlines and one for United Airlines.[24]

- DC-10-15

- The -15 variant was designed for use at hot and high airports. The series 15 is basically a -10 fitted with higher-thrust GE CF6-50C2F (derated DC-10-30 engines) powerplants.[25] The −15 was first ordered in 1979 by Mexicana and Aeroméxico. Seven were completed between 1981 and 1983.[26]

Long-range variants

- DC-10-30

- A long-range model and the most common model produced. It was built with General Electric CF6-50 turbofan engines and larger fuel tanks to increase range and fuel efficiency, as well as a set of rear center landing gear to support the increased weight. It was very popular with European flag carriers. A total of 163 were built from 1972 to 1988 and delivered to 38 different customers.[27] The model was first delivered to KLM and Swissair on November 21, 1972 and first introduced in service on December 15, 1972 by the latter.

- DC-10-30CF

- The convertible cargo/passenger transport version of the -30. The first deliveries were to Overseas National Airways and Trans International Airlines in 1973. A total of 27 were built.[28]

- DC-10-30ER

- The extended-range version of the -30. The -30ER aircraft has a higher maximum takeoff weight of 590,000 lb (267,600 kg), is powered by three GE CF6-50C2B engines each producing 54,000 lbf (240 kN) of thrust and is equipped with an additional fuel tank in the rear cargo hold.[29][30] It has an additional 700 mi of range to 6,600 mi (5,730 nmi, 10,620 km). The first of this variant was delivered to Finnair in 1981. A total of six were built and five −30s were later converted to −30ERs.

- DC-10-30AF

- Also known as the DC-10-30F. This was the all freight version of the -30. Production was to start in 1979, but Alitalia did not confirm its order then. Production began in May 1984 after the first aircraft order from FedEx. A total of 10 were built.[31]

- DC-10-40

- The first long-range version fitted with Pratt & Whitney JT9D engines. Originally designated DC-10-20, this model was renamed DC-10-40 after a special request from Northwest Orient Airlines as the aircraft was much improved compared to its original design, with a higher MTOW (on par with the Series 30) and more powerful engines. The airline's president wanted to advertise he had the latest version.[32][33] The company also wanted its aircraft to be equipped with the same engines as its Boeing 747s for fleet commonality.[34] Northwest Orient Airlines and Japan Airlines were the only airlines to order the Series 40 with 22 and 20 aircraft, respectively. Engine improvements led to the DC-10-40s delivered to Northwest featuring Pratt & Whitney JT9D-20 engines producing 50,000 lbf (222 kN) of thrust and a MTOW of 555,000 lb (251,815 kg). The -40s for Japan Airlines were equipped with P&W JT9D-59A engines that produced a thrust of 53,000 lbf (235.8 kN) and a MTOW of 565,000 lb (256,350 kg).[35] Forty-two were built from 1973 to 1983.[36] Externally, the DC-10-40 can be distinguished from the -30 series by a slight bulge near the front of the nacelle for the #2 (tail) engine.

Proposed variants

- DC-10-20

- A proposed version of the DC-10-10 with extra fuel tanks, 3-ft (0.9 m) extensions on each wingtip and a rear center landing gear. It was to use Pratt & Whitney JT9D-15 turbofan engines, each producing 45,500 lbf (203 kN) of thrust, with a maximum takeoff weight of 530,000 lb (240,400 kg). But engine improvements led to increased thrust and increased takeoff weight.[35] Northwest Orient Airlines, one of the launch customers for this longer-range DC-10 requested the name change to DC-10-40.[32]

- DC-10-50

- A proposed version with Rolls-Royce RB211-524 engines for British Airways. The order never came and the plans for the DC-10-50 were abandoned after British Airways ordered the Lockheed L-1011-500 instead.[37]

- DC-10 Twin

- Two-engine designs were studied for the DC-10 before the design settled on the three-engine configuration. Later a shortened DC-10 version with two engines was proposed against the Airbus A300.[38]

Tanker versions

The KC-10 Extender is a military version of the DC-10-30CF for aerial refueling. The aircraft was ordered by the U.S. Air Force and delivered from 1981 to 1988. A total of 60 were built.[39]

The KDC-10 is an aerial refueling tanker for the Royal Netherlands Air Force. These were converted from civil airliners (DC-10-30CF) to a similar standard as the KC-10. Also, commercial refueling companies Omega Aerial Refueling Services[40][41] and Global Airtanker Service[42][43] operate two KDC-10 tankers for lease. Four have been built.

The DC-10 Air Tanker is a DC-10-based firefighting tanker aircraft, using modified water tanks from Erickson Air-Crane.

MD-10 upgrade

.jpg)

The MD-10 is an upgrade to add a glass cockpit to the DC-10 with the re-designation to MD-10. The upgrade included an Advanced Common Flightdeck used on the MD-11 and was launched in 1996.[44] The new cockpit eliminated the need for the flight engineer position and allowed common type rating with the MD-11. This allows companies such as FedEx Express, which operate both the MD-10 and MD-11, to have a common pilot pool for both aircraft. The MD-10 conversion now falls under the Boeing Converted Freighter program where Boeing's international affiliate companies perform the conversions.[45]

Operators

In July 2019, there were 31 DC-10s and MD-10s in airline service with operators FedEx Express (30), and TAB Airlines (1).[46] On January 8, 2007, Northwest Airlines retired its last remaining DC-10 from scheduled passenger service,[47] thus ending the aircraft's operations with major airlines. Regarding the retirement of Northwest's DC-10 fleet, Wade Blaufuss, spokesman for the Northwest chapter of the Air Line Pilots Association said, "The DC-10 is a reliable airplane, fun to fly, roomy and quiet, kind of like flying an old Cadillac Fleetwood. We're sad to see an old friend go."[48] Biman Bangladesh Airlines was the last commercial carrier to operate the DC-10 in passenger service.[49][50][51] The airline flew the DC-10 on a regular passenger flight for the last time on February 20, 2014, from Dhaka, Bangladesh to Birmingham, UK.[50][52] Local charter flights were flown in the UK until February 24, 2014.[53]

Non-airline operators include the Royal Netherlands Air Force with two DC-10-30CF-based KDC-10 tanker aircraft, the USAF with its 59 KC-10s, and the 10 Tanker Air Carrier with its modified DC-10-10 used for fighting wildfires.[54] Orbis International has used a DC-10 as a flying eye hospital. Surgery is performed on the ground and the operating room is located between the wings for maximum stability. In 2008, Orbis chose to replace its aging DC-10-10 with a DC-10-30 jointly donated by FedEx and United Airlines.[55][56] The newer DC-10 converted into MD-10 configuration, and began flying as an eye hospital in 2010.[56][57][58] One former American Airlines DC-10-10 is operated by the Missile Defense Agency as the Widebody Airborne Sensor Platform (WASP).[59]

Accidents and incidents

As of September 2015, the DC-10 had been involved in 55 accidents and incidents,[60] including 32 hull-loss accidents,[61] with 1,261 occupant fatalities.[62] Of these accidents and incidents, it has been involved in nine hijackings resulting in one death and a bombing resulting in 170 occupant fatalities.[62] Despite its poor safety record in the 1970s, which gave it an unfavorable reputation,[63] the DC-10 has proved to be a reliable aircraft with a low overall accident rate as of 1998.[64] The DC-10's initially poor safety record has continuously improved as design flaws were rectified and fleet hours increased.[64] The DC-10's lifetime safety record is comparable to similar second-generation passenger jets as of 2008.[65]

Cargo door problem and other major accidents

Instead of conventional inward-opening plug doors, the DC-10 has cargo doors that open outward; this allows the cargo area to be completely filled, as the doors do not occupy otherwise usable interior space when open. To overcome the outward force from pressurization of the fuselage at high altitudes, outward-opening doors must use heavy locking mechanisms. In the event of a door lock malfunction, there is great potential for explosive decompression.[66]

American Airlines Flight 96

On June 12, 1972, American Airlines Flight 96 lost its aft cargo door above Windsor, Ontario. Before takeoff, an airport employee had forced the door shut, and although the door appeared secure, the internal locking mechanism was not fully engaged. When the aircraft reached approximately 11,750 feet (3,580 m) in altitude, the door blew out, and the resulting explosive decompression collapsed the cabin floor.[67] Many control cables to the empennage were cut, leaving the pilots with very limited control of the aircraft.[68][68][69] The crew performed an emergency landing by using the ailerons, right elevator, some limited rudder trim, and asymmetrical thrust of the wing engines.[70] All 67 passengers evacuated safely.[71]

U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigators found the cargo door design to be dangerously flawed, as the door could be closed without the locking mechanism fully engaged, and this condition was not apparent from visual inspection of the door nor from the cargo-door indicator in the cockpit. The NTSB recommended modifications to make it readily apparent to baggage handlers when the door was not secured, and also recommended adding vents to the cabin floor, so that in an explosive decompression, the pressure difference between the cabin and cargo bay could quickly equalize without damaging other aircraft systems.[67] Although many carriers voluntarily modified the cargo doors, no airworthiness directive was issued, due to a gentlemen's agreement between the head of the FAA, John H. Shaffer, and the head of McDonnell Douglas's aircraft division, Jackson McGowen. McDonnell Douglas made some modifications to the cargo door, but the basic design remained unchanged, and problems persisted.[67]

Turkish Airlines Flight 981

On March 3, 1974, in an accident circumstantially similar to American Airlines Flight 96, a cargo-door blowout caused Turkish Airlines Flight 981 to crash near Ermenonville, France.[67] All 346 people on board died[72] in one of the deadliest air crashes of all time.[73] The cargo door of Flight 981 had not been fully locked, though it appeared so to both cockpit crew and ground personnel. The Turkish aircraft had a seating configuration that exacerbated the effects of decompression, and as the cabin floor collapsed into the cargo bay, control cables were severed and the aircraft became uncontrollable.[67] Crash investigators found that the DC-10's relief vents were not large enough to equalize the pressure between the passenger and cargo compartments during explosive decompression.[72] Following this crash, a special subcommittee of the United States House of Representatives investigated the cargo-door issue and the certification by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) of the original design.[74] An airworthiness directive was issued, and all DC-10s underwent mandatory door modifications.[74] The DC-10 experienced no more major incidents related to its cargo door after FAA-approved changes were made.[67]

American Airlines Flight 191

On May 25, 1979, American Airlines Flight 191 crashed immediately after takeoff from Chicago's O'Hare Airport.[75] As the airliner was taking off, the left engine and pylon assembly swung upward over the top of the wing, severing critical hydraulic and electrical lines before falling away. The leading edge slat actuators lost hydraulic pressure and the slats retracted due to aerodynamic forces, causing the left wing to stall. This condition, combined with asymmetric thrust due to the missing engine, caused the aircraft to rapidly roll to the left, descend, and crash, killing all 271 people on board and two individuals on the ground.[76] The loss of Flight 191 remains the deadliest single-aircraft aviation accident in U.S. history. The crash and its aftermath were widely covered by the media and dealt a severe blow to the DC-10's reputation and sales.

The crash highlighted major deficiencies in the DC-10 design: the lack of a mechanism to lock the leading-edge slats in the event of a hydraulic or pneumatic actuation failure; a lack of redundancy in the stall warning system; and the failure of McDonnell Douglas to adequately consider "multiple failures of other systems" that could result from an in-flight pylon separation.[77] Critical warning system components were torn away with the engine, thus preventing the flight crew—who could not see the wings from the cockpit—from realizing the cause of their predicament and taking appropriate corrective action.[78] Following the crash, the FAA withdrew the DC-10's type certificate on June 6, 1979, grounding all 138 U.S.-registered DC-10s along with those from other nations with bilateral agreements with the United States, and banning all other DC-10s from U.S. airspace. Even ferry flying within U.S. airspace was forbidden except to allow foreign air carriers to return their DC-10s to overseas maintenance bases.[79] These measures were rescinded five weeks later on July 13, 1979, after modifications were made to the slat actuation and position systems, along with stall warning and power supply changes.[77][80]

NTSB officials discovered that American Airlines mechanics had removed the engine and its pylon as a unit, rather than removing the engine from the pylon before removing the pylon from the wing, as recommended by McDonnell Douglas. The non-standard procedure caused structural damage that the NTSB deemed to have caused the engine separation and the subsequent crash. It was later discovered that this short-cut procedure, believed to save many man-hours, was being used by both American Airlines and Continental Airlines, although McDonnell Douglas had advised against it.[77] In November 1979, the FAA fined American Airlines $500,000 and Continental Airlines $100,000 for using this incorrect maintenance procedure.[77][81]

In the wake of the grounding, the FAA convened a safety panel under the auspices of the National Academy of Sciences to evaluate the design of the DC-10 and the U.S. regulatory system in general. The panel's report, published in June 1980, found "critical deficiencies in the way the Government certifies the safety of American-built airliners", focusing on a shortage of FAA expertise during the certification process and a corresponding overreliance on McDonnell Douglas to ensure that the design was safe. Writing for The Air Current, aviation journalist Jon Ostrower likens the panel's conclusions to those of a later commission convened after the 2019 grounding of the Boeing 737 MAX. Ostrower faults both manufacturers for focusing on the letter of the law regarding regulatory standards, taking a design approach that addresses how the pilots could address single system failures, without adequately considering scenarios in which multiple simultaneous malfunctions of different systems could occur.[78]

United Airlines Flight 232

On July 19, 1989, United Airlines Flight 232 crashed at Sioux City, Iowa after the tail engine suffered an uncontained engine failure earlier in the flight, disabling all hydraulic systems and rendering most flight controls inoperable. The flight crew, led by Captain Al Haynes and assisted by DC-10 flight instructor flying as a passenger (Dennis E. "Denny" Fitch), managed to perform a partially controlled emergency landing by constantly adjusting the thrust of the remaining two engines; 185 people on board survived, but 111 others died, and the aircraft was destroyed.[82]

The DC-10 lacks non-hydraulic backup flight controls because the control surfaces are too large to be operated easily without hydraulic assistance, and it was considered extremely improbable that all three hydraulic systems would fail. However, due to their close proximity under the tail engine, the engine failure ruptured all three, resulting in total loss of control to the elevators, ailerons, spoilers, horizontal stabilizer, rudder, flaps and slats.[82] Following the accident, hydraulic fuses were installed in the #3 hydraulic system below the tail engine on all DC-10 aircraft to ensure that sufficient control remains if all three hydraulic systems are damaged in this area. It is still possible to lose all three hydraulic systems elsewhere. This nearly happened to a cargo airliner in 2002 when a main-gear tire exploded in the left wing wheel well, causing total loss of pressure in the #1 and the #2 hydraulic systems. The #3 system was dented but not penetrated.[83]

Other notable accidents

Other notable accidents are:

- November 3, 1973: National Airlines Flight 27, a DC-10-10 cruising at 39,000 feet, experienced an uncontained failure of the right (number 3) engine. One cabin window separated from the fuselage after it was struck by debris flung from the exploding engine. The passenger sitting next to that window was killed and ejected from the aircraft. The crew initiated an emergency descent, and landed the aircraft safely.[84]

- December 17, 1973: Iberia Airlines Flight 933 crashed and struck the ALS system at Boston Logan International Airport which collapsed the front landing gear. All 168 passengers and crew survived. This is the first hull loss of a DC-10 aircraft.

- November 12, 1975: ONA Flight 032, a DC-10 on a ferry flight struck a heavy flock of seagulls while on its takeoff roll from JFK International Airport, New York. The captain aborted below V1 speed, but the #3 engine exploded, causing a partial braking failure. The landing gear collapsed and fire eventually destroyed the plane. All 139 ONA employees on board survived. Two were seriously injured, while 30 others had minor injuries.[85]

- January 2, 1976: An ONA DC-10 experienced an undershoot on a short runway in Istanbul, Turkey. The aircraft touched the ground and crash landed, then a fire in the #1 engine started. The aircraft was destroyed. All passengers survived.[86]

- March 1, 1978: Continental Airlines Flight 603, a DC-10-10, began its take-off from Los Angeles International Airport. Approaching V1 in the takeoff roll, the recapping tread a tire on the left main landing gear separated from the tire and led to two adjacent tires blowing. The blowouts ruptured a fuel tank, which combined with the excessive heat from the aborted take off maneuver, resulted in a massive fire. Two passengers were killed in the ensuing evacuation and two died later from injuries sustained in the accident.

- October 31, 1979: Western Airlines Flight 2605, a DC-10-10, collided with construction equipment after landing on a closed runway at Mexico City International Airport, killing 72 of the 88 people on board and one person on the ground. The crash was caused by failure to follow proper landing guidelines in consideration of the fog on the runway.[87]

- November 28, 1979: Air New Zealand Flight 901, DC-10-30 ZK-NZP, crashed into Mount Erebus on Ross Island, Antarctica during a sightseeing flight over the continent, killing all 257 on board. The accident was caused by the flight coordinates being altered without the flight crew's knowledge, combined with unique Antarctic weather conditions.[88]

- January 23, 1982: World Airways Flight 30, DC-10-30CF registration N113WA, overran the runway at Boston Logan International Airport. All 12 crew survived, but two of the 200 passengers were never found.[89]

- September 13, 1982: Spantax Flight 995, DC-10-30CF EC-DEG, was destroyed by fire after an aborted take-off at Málaga, Spain. A total of 50 passengers were killed and 110 injured due to the flames.

- May 21, 1988: American Airlines Flight 70, DC-10-30 N136AA, overran Runway 35L at Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport after the flight crew attempted a rejected takeoff. The aircraft continued to accelerate for several seconds before slowing, and ran 1,100 feet (335 m) past the runway threshold, collapsing the nose landing gear. 2 crew were seriously injured and the remaining 12 crew and 240 passengers escaped safely; the aircraft was severely damaged and was written off. The accident was attributed to a shortcoming in the original design standards; there had been no requirement to test whether partially worn brake pads could stop the aircraft during a rejected takeoff, and 8 of the 10 worn pad sets had failed.[90][91]

- July 27, 1989: Korean Air Flight 803, DC-10-30 HL7328, crashed short of the runway in bad weather while trying to land at Tripoli, Libya. A total of 75 of the 199 on board plus another 4 people on the ground were killed in the accident.[92]

- September 19, 1989: UTA Flight 772, DC-10-30 N54629, crashed in the Ténéré Desert in Niger following an in-flight bomb explosion, claiming the lives of all 170 on board.

- December 21, 1992: Martinair Flight 495, DC-10-30CF PH-MBN, crashed while landing in bad weather at Faro, Portugal killing 54 passengers and crew.[93][94]

- April 7, 1994: Federal Express Flight 705, DC-10-30 N306FE, experienced an attempted hijacking. FedEx employee Auburn Calloway tried to hijack the aircraft with the intention of crashing it, but the crew fought him off and returned to Memphis. The co-pilot used a number of aerobatic maneuvers to assist his colleagues in fighting off the hijacker.[95]

- June 13, 1996: Garuda Indonesia Flight 865, DC-10-30 PK-GIE, had just taken off from Fukuoka Airport, Japan when a high-pressure blade from engine #3 separated. The aircraft was just a few feet above the runway, and the pilot decided to abort the take-off. Consequently, the DC-10 skidded off the runway and came to a halt 1,600 ft (490 m) past it, losing one of its engines and its landing gear. Three passengers perished in the accident.

- July 25, 2000: Continental Airlines Flight 55, operated by a DC-10-30 registered as N13067, shed a strip of metal from the thrust reverser cowl door of the number 3 engine, which landed on the runway at Charles de Gaulle Airport upon take off. Minutes later, Air France Flight 4590, operated by a Concorde, ran over the metal strip at near V1 speed, bursting a tire and causing a fuel tank to rupture and burst into flames. The Concorde's pilots attempted to keep control of the aircraft, but it stalled and crashed. The strip of metal was traced to third-party replacement parts not approved by the Federal Aviation Administration.[96]

Aircraft on display

- The preserved forward fuselage segment of Monarch Airlines' DC-10-30, G-DMCA,[97] is on display at Manchester Airport Aviation Viewing Park, where it is used for teaching and school visits.

- DC-10-30 9G-ANB, which previously belonged to Ghana Airways, is on display and in use as the La Tante DC10 Restaurant in Accra, Ghana.[98]

- DC-10-10 N220AU "Flying Eye Hospital" previously owned by Orbis International was retired in 2016 and is on display at the Pima Air & Space Museum in Tucson, Arizona.[99][100]

- DC-10-30 Z-AVT "Victor Trimble" previously owned by British Caledonian Airways is preserved as a night club in Bali. The tail end of the aircraft featuring the third engine is mounted on a rooftop in Bali.[101][102]

Specifications

| Variant | -10 | -30 | -40 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cockpit crew | Three | |||

| Std. seating | 270 (222Y 8-abreast @ 34" + 48J 6-abreast @ 38") | |||

| Max. seating | 399Y (10-abreast @ 29–34" pitch) layout, FAA exit limit: 380[104] | |||

| Cargo | 26 LD3 layout, main deck: 22 88×125″ or 30 88x108″ pallets | |||

| Length | 182 ft 3.1 in / 55.55 m | 181 ft 7.2 in / 55.35 m | 182 ft 2.6 in / 55.54 m | |

| Height | 57 ft 6 in / 17.53 m | 57 ft 7 in / 17.55 m | ||

| Wingspan | 155 ft 4 in / 47.35 m | 165 ft 4 in / 50.39 m | ||

| Wing area[105] | 3,550 sq ft (330 m2) | 3,647 sq ft (338.8 m2) | ||

| Width | 19 ft 9 in (6.02 m) fuselage, 224 in (569 cm) interior | |||

| OEW (pax) | 240,171 lb / 108,940 kg | 266,191 lb / 120,742 kg | 270,213 lb / 122,567 kg | |

| MTOW | 430,000 lb / 195,045 kg | 555,000 lb / 251,744 kg | ||

| Max. payload | 94,829 lb / 43,014 kg | 101,809 lb / 46,180 kg | 97,787 lb 44,356 kg | |

| Fuel capacity | 21,762 US gal / 82,376 L | 36,652 US gal / 137,509 L | ||

| Engines ×3 | GE CF6-6D | GE CF6-50C | PW JT9D-59A | |

| Thrust ×3[105] | 40,000 lbf / 177.92 kN | 51,000 lbf / 226.85 kN | 53,000 lbf / 235.74 kN | |

| Cruise | Mach 0.82 (473 kn; 876 km/h) typical, Mach 0.88 (507 kn; 940 km/h) MMo[104] | |||

| Range[lower-alpha 1] | 3,500 nmi (6,500 km) | 5,200 nmi (9,600 km) | 5,100 nmi (9,400 km) | |

| Takeoff[lower-alpha 2] | 9,000 ft (2,700 m) | 10,500 ft (3,200 m) | 9,500 ft (2,900 m) | |

| Ceiling | 42,000 ft (12,800 m)[104] | |||

- M0.82, 270 pax @ 205 lb each

- MTOW, SL, ISA

Deliveries

| 1971 | 1972 | 1973 | 1974 | 1975 | 1976 | 1977 | 1978 | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | 1984 | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | 52 | 57 | 48 | 42 | 19 | 14 | 18 | 36 | 40 | 25 | 11 | 12 | 10 | 11 | 17 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 446 |

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

Related lists

References

Citations

- "Commercial Airplanes: DC-10 Family". boeing.com. Archived from the original on December 13, 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2011.

- "Airliner price index". Flight International. August 10, 1972. p. 183.

- Bradsher, Keith (July 20, 1989). "Troubled History of the DC-10 Includes Four Major Crashes". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Waddington 2000, pp. 6–18.

- Endres 1998, p. 13.

- Transatlantic Betrayal. Andrew Porter. Amberley. 2013

- Endres 1998, p. 16.

- "American Orders 25 'Airbus' Jets." St. Petersburg Times, September 14, 2011.

- Endres 1998, pp. 25–26.

- Endres 1998, p. 28.

- Endres 1998, p. 52.

- Aviation Daily July 29, 1971

- "DC-10 Technical Specifications." Archived February 4, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Boeing. Retrieved: March 12, 2011.

- Endres 1998, pp. 32–33.

- Waddington 2000, p. 70.

- Endres 1998, pp. 34–35.

- "McDonnell Douglas DC-10/KC-10 Transport". boeing.com. Archived from the original on March 12, 2006. Retrieved February 28, 2006.

- Roach, John and Anthony Eastwood. "Jet Airliner Production List, Volume 2." The Aviation Hobby Shop online, July 2006. Retrieved: September 19, 2010.

- "Air Progress". Air Progress: 16. September 1971.

- Steffen 1998, p. 120.

- Aircraft Value News (November 12, 2018). "Transitioning Product Line Impacts Values of Outgoing Models".

- Endres 1998, pp. 36–37, 45.

- Endres 1998, pp. 36, 46–47.

- Steffen 1998, pp. 12, 14–16.

- Steffen 1998, pp. 12, 118.

- Endres 1998, pp. 62, 123–124.

- Endres 1998, pp. 57, 112–124.

- Steffen 1998, pp. 12–13.

- Endres 1998, pp. 34–37.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 30, 2017. Retrieved June 23, 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Steffen 1998, p. 13.

- Waddington 2000, pp. 70–71.

- Endres 1998, pp. 56–57.

- Endres 1998, p. 21.

- Endres 1998, p. 21, 35, 56.

- Waddington 2000, pp. 137–144.

- Waddington 2000, p. 89.

- "DC-10 Twin briefing" (PDF). Flight International. June 7, 1973.

- Endres 1998, pp. 65–67.

- "Omega Air Refuelling FAQs". Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- "What We Do". Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- "KDC-10 Air Refueling Tanker Aircraft". 2004. Archived from the original on July 4, 2008. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- "Global Airtanker Service KDC-10 In-flight Refuelling Aircraft". airforce-technology.com. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- "McDonnell Douglas and Federal Express to Launch MD-10 Program" Archived November 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. McDonnell Douglas, September 16, 1996. Retrieved: August 6, 2011.

- "World's First 767-300 Boeing Converted Freighter Goes to ANA" Archived June 22, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Boeing. Retrieved: June 16, 2008.

- Thisdell and Seymour Flight International 30 July − 5 August 2019, p. 46.

- "Northwest Brings Customer Comforts Of Airbus A330 Aircraft To Twin Cities-Honolulu Route." Archived January 30, 2013, at Archive.today Northwest Airlines, January 8, 2007. Retrieved: February 9, 2007.

- Reed, Ted. "End of an Era at Northwest." Archived July 14, 2006, at the Wayback Machine TheStreet.com, June 30, 2006. Retrieved: February 9, 2007.

- "Fleet Info". Biman Bangladesh Airlines. Archived from the original on July 19, 2013.

- Richardson, Tom (February 22, 2014). "Remembering the DC-10: End of an era or good riddance?". BBC News Online. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- "Last Passenger DC-10 Makes Last Flight?". AVweb, December 6, 2013.

- "The DC-10 makes its final scheduled passenger flight". USA Today, February 24, 2014.

- "Biman Bangladesh Airlines operates the last McDonnell Douglas DC-10 passenger flight". World Airline News. February 25, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- Sarsfield, Kate. "Firefighting DC-10 available to lease." Flight International, March 30, 2009.

- Kaminski-Morrow, David. "Orbis to convert ex-United DC-10-30 into new airborne eye hospital." Flight International, April 8, 2008.

- "The ORBIS MD-10 Project." Archived June 13, 2010, at the Wayback Machine orbis.org. Retrieved: September 19, 2010.

- "ORBIS Flying Eye Hospital Visits Los Angeles to Collaborate with MD-10 Project Supporters." Archived June 13, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Orbis. Retrieved: July 11, 2010.

- "ORBIS Launches MD-10 Flying Eye Hospital Project." slideshare.net. Retrieved: September 19, 2010.

- "Space: Widebody Airborne Sensor Platform (WASP)." globalsecurity.org. Retrieved: March 12, 2011.

- "McDonnell Douglas DC-10 incidents." Aviation-Safety.net, May 10, 2015. Retrieved: May 12, 2015.

- "McDonnell Douglas DC-10 hull-losses." Aviation-Safety.net, May 10, 2015. Retrieved: May 12, 2015.

- "McDonnell Douglas DC-10 Statistics." Aviation-Safety.net May 10, 2015. Retrieved: May 12, 2015.

- Hopfinger, Tony. "I Will Survive: Laurence Gonzales: 'Who Lives, Who Dies, and Why'." Anchorage Press, October 23–29, 2003. Retrieved: August 27, 2009.

- Endres 1998, p. 109.

- "Statistical Summary of Commercial Jet Airplane Accidents (1959–2008)." Boeing. Retrieved: January 11, 2010.

- Waddington 2000, pp. 85–86.

- "Behind Closed Doors". Air Crash Investigation, Mayday (TV series). National Geographic Channel, Season 5, Number 2.

- Fielder and Birsch 1992, p. 94.

- "NTSB-AAR-73-02 Report, Aircraft Accident Report: American Airlines, Inc. McDonnell Douglas DC-10-10, N103AA. Near Windsor, Ontario, Canada. June 12, 1972". National Transportation Safety Board, Washington, DC, February 28, 1973.

- Waddington 2000, p. 67.

- Endres 1998, p. 54.

- "Turkish Airlines DC-10, TC-JAV. Report on the accident in the Ermenonville Forest, France on March 3, 1974". UK Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB), February 1976.

- "Plane crash in France kills 346". St. Petersburg Times, March 4, 1974. Retrieved: May 30, 2012.

- Endres 1998, p. 55.

- "American Airlines 191". Archived August 13, 2006, at the Wayback Machine airdisaster.com. Retrieved: January 11, 2010.

- Endres 1998, p. 62.

- "Aircraft Accident report, DC-10-10, N110A, NTSB, 1979". libraryonline.erau.edu. Retrieved: September 19, 2010.

- "Searching for 40-year old lessons for Boeing in the grounding of the DC-10". The Air Current. October 15, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- "DC-10 Type Certificate Lifted". awin.aviationweek.com. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

- Endres 1998, pp. 63–64.

- "Flight 191 accident description". Aviation-Safety.net. Retrieved: January 11, 2010.

- "NTSB/AAR-90/06, Aircraft Accident Report United Airlines Flight 232, McDonnell Douglas DC-10-40, Sioux Gateway Airport, Sioux City, Iowa, July 19, 1989" summary, report Archived January 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. NTSB, November 1, 1990.

- "WAS02RA037, NTSB Factual Report". NTSB.

- Mcarthur Job. Air Disaster Volume 1. Aerospace Publications Pty Ltd. 1994. ISBN 1-875671-11-0

- NTSB report, Identification: DCA76AZ010

- NTSB report, Identification: DCA76RA017

- "Accident description". Aviation-safety.net. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- Swarbrick, Nancy (July 13, 2012). "Air crashes – The 1979 Erebus crash". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved May 24, 2015.

- "AAR-85-06, World Airways, Inc., Flight 30H, McDonnell Douglas DC-10-30CF, N113WA, Boston-Logan Int'l Airport, Boston, Massachusetts, Jan. 23, 1982 (Revised)" Archived October 4, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. U.S. National Transportation Safety Board, July 10, 1985.

- "NTSB Aviation Accident Final Report FTW88NA106". National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- "ASN Accident Description". Aviation Safety Network. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

- "DC-10 accident entry: July 27, 1989." Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved: July 11, 2010.

- "Crash of a Dutch DC-10 kills 54 at a resort airport in Portugal". New York Times. December 22, 1992. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- "Survivors relive horror as 54 die in crash". The Toronto Star. December 22, 1992. Retrieved February 2, 2017 – via Lexus Nexus.

- "FedEX Flight 705 Hijacking, April 7, 1994". Aviation Safety Network, Flight Safety Foundation

- "'Poor repair' to DC-10 was cause of Concorde crash". Flight Global. October 24, 2000. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- "Aviation Photo Search".

- "In pictures: Plane eating in Ghana". BBC. BBC. January 15, 2014. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- "DC 10". Pima Air & Space Museum. PimaAir.org. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- Gurrola, Adrian (November 22, 2016). "Flying eye hospital makes final stop in Southern Arizona". News 4 Tucson. KVOA.com. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- "Z-AVT Avient Aviation McDonnell Douglas DC-10-30". www.planespotters.net. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- "20 photos of Bali's Hi-Fi nightclub built in an abandoned DC-10 airplane". Mixmag Asia. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- "DC-10 Airplane Characteristics for Airport Planning" (PDF). McDonnell Douglas. May 2011.

- "Type Certificate Data Sheet A22WE" (PDF). FAA. April 30, 2018.

- "DC-10" (PDF). Boeing. 2007.

Bibliography

- Endres, Günter. McDonnell Douglas DC-10. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing Company, 1998. ISBN 0-7603-0617-6.

- Fielder, J.H. and D. Birsch. The DC-10 Case: A Study in Applied Ethics, Technology, and Society. Albany, New York: SUNY Press, 1992. ISBN 0-7914-1087-0.

- Kocivar, Ben. "Giant Tri-Jets Are Coming". Popular Science, December 1970, pp. 50–52, 116. ISSN 0161-7370.

- Porter, Andrew. "Transatlantic Betrayal " The RB211 and the Demise of Rolls-Royce LTD. Stroud. UK. Amberley, 2013. ISBN 978-1-4456-0649-1

- Steffen, Arthur, A. C. McDonnell Douglas DC-10 and KC-10 Extender. Hinckley, Leicester, UK: Aerofax, 1998. ISBN 1-85780-051-6.

- Waddington, Terry. McDonnell Douglas DC-10. Miami, Florida: World Transport Press, 2000. ISBN 1-892437-04-X.

- "World Airliner Census". Flight International, Volume 184, Number 5403, August 13–19, 2013, pp. 40–58.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to McDonnell Douglas DC-10. |

- DC-10/KC-10 history on Boeing.com

- "DC-10 Passenger" (PDF). Boeing. 2007.

- Robert R. Ropelewski (August 30, 1971). "DC-10 Minimizes Crew Workload" (PDF). Aviation Week. 'Simple sophistication' of aircraft, with improvements in training, credited with reducing flight time for type rating.