Mango

A mango is a juicy stone fruit (drupe) produced from numerous species of tropical trees belonging to the flowering plant genus Mangifera, cultivated mostly for their edible fruit. Most of these species are found in nature as wild mangoes. The genus belongs to the cashew family Anacardiaceae. Mangoes are native to South Asia,[1][2] from where the "common mango" or "Indian mango", Mangifera indica, has been distributed worldwide to become one of the most widely cultivated fruits in the tropics. Other Mangifera species (e.g. horse mango, Mangifera foetida) are grown on a more localized basis.

Worldwide, there are several hundred cultivars of mango. Depending on the cultivar, mango fruit varies in size, shape, sweetness, skin color, and flesh color which may be pale yellow, gold, or orange.[1] Mango is the national fruit of India, Haiti, and the Philippines,[3] and the national tree of Bangladesh.[4] It is the summer national fruit of Pakistan.

Etymology

The English word "mango" (plural "mangoes" or "mangos") originated from the Tamil word manga (or mangga) during the spice trade period with South India in the 15th and 16th centuries.[5]

Description

Mango trees grow to 35–40 m (115–131 ft) tall, with a crown radius of 10 m (33 ft). The trees are long-lived, as some specimens still fruit after 300 years.[7] In deep soil, the taproot descends to a depth of 6 m (20 ft), with profuse, wide-spreading feeder roots and anchor roots penetrating deeply into the soil.[1] The leaves are evergreen, alternate, simple, 15–35 cm (5.9–13.8 in) long, and 6–16 cm (2.4–6.3 in) broad; when the leaves are young they are orange-pink, rapidly changing to a dark, glossy red, then dark green as they mature.[1] The flowers are produced in terminal panicles 10–40 cm (3.9–15.7 in) long; each flower is small and white with five petals 5–10 mm (0.20–0.39 in) long, with a mild, sweet fragrance.[1] Over 500 varieties of mangoes are known,[1] many of which ripen in summer, while some give a double crop.[8] The fruit takes four to five months from flowering to ripen.[1]

The ripe fruit varies according to cultivar in size, shape, color, sweetness, and eating quality.[1] Depending on cultivar, fruits are variously yellow, orange, red, or green.[1] The fruit has a single flat, oblong pit that can be fibrous or hairy on the surface, and does not separate easily from the pulp.[1] The fruits may be somewhat round, oval, or kidney-shaped, ranging from 5–25 centimetres (2–10 in) in length and from 140 grams (5 oz) to 2 kilograms (5 lb) in weight per individual fruit.[1] The skin is leather-like, waxy, smooth, and fragrant, with color ranging from green to yellow, yellow-orange, yellow-red, or blushed with various shades of red, purple, pink or yellow when fully ripe.[1]

Ripe intact mangoes give off a distinctive resinous, sweet smell.[1] Inside the pit 1–2 mm (0.039–0.079 in) thick is a thin lining covering a single seed, 4–7 cm (1.6–2.8 in) long. Mangoes have recalcitrant seeds which do not survive freezing and drying.[9] Mango trees grow readily from seeds, with germination success highest when seeds are obtained from mature fruits.[1]

Cultivation

Mangoes have been cultivated in South Asia for thousands of years and reached Southeast Asia between the fifth and fourth centuries BCE. By the 10th century CE, cultivation had begun in East Africa.[10] The 14th-century Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta reported it at Mogadishu.[11] Cultivation came later to Brazil, Bermuda, the West Indies, and Mexico, where an appropriate climate allows its growth.[10]

The mango is now cultivated in most frost-free tropical and warmer subtropical climates; almost half of the world's mangoes are cultivated in India alone, with the second-largest source being China.[12][13][14] Mangoes are also grown in Andalusia, Spain (mainly in Málaga province), as its coastal subtropical climate is one of the few places in mainland Europe that permits the growth of tropical plants and fruit trees. The Canary Islands are another notable Spanish producer of the fruit. Other cultivators include North America (in South Florida and the California Coachella Valley), South and Central America, the Caribbean, Hawai'i, south, west, and central Africa, Australia, China, South Korea, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Southeast Asia. Though India is the largest producer of mangoes, it accounts for less than 1% of the international mango trade; India consumes most of its own production.[15][16]

Many commercial cultivars are grafted on to the cold-hardy rootstock of Gomera-1 mango cultivar, originally from Cuba. Its root system is well adapted to a coastal Mediterranean climate.[17] Many of the 1,000+ mango cultivars are easily cultivated using grafted saplings, ranging from the "turpentine mango" (named for its strong taste of turpentine[18]) to the Bullock's Heart. Dwarf or semidwarf varieties serve as ornamental plants and can be grown in containers. A wide variety of diseases can afflict mangoes.

Cultivars

There are many hundreds of named mango cultivars. In mango orchards, several cultivars are often grown in order to improve pollination. Many desired cultivars are monoembryonic and must be propagated by grafting or they do not breed true. A common monoembryonic cultivar is 'Alphonso', an important export product, considered as "the king of mangoes".[19]

Cultivars that excel in one climate may fail elsewhere. For example, Indian cultivars such as 'Julie', a prolific cultivar in Jamaica, require annual fungicide treatments to escape the lethal fungal disease anthracnose in Florida. Asian mangoes are resistant to anthracnose.

The current world market is dominated by the cultivar 'Tommy Atkins', a seedling of 'Haden' that first fruited in 1940 in southern Florida and was initially rejected commercially by Florida researchers.[20] Growers and importers worldwide have embraced the cultivar for its excellent productivity and disease resistance, shelf life, transportability, size, and appealing color.[21] Although the Tommy Atkins cultivar is commercially successful, other cultivars may be preferred by consumers for eating pleasure, such as Alphonso.[19][21]

Generally, ripe mangoes have an orange-yellow or reddish peel and are juicy for eating, while exported fruit are often picked while underripe with green peels. Although producing ethylene while ripening, unripened exported mangoes do not have the same juiciness or flavor as fresh fruit.

| Mango* production – 2018 | |

|---|---|

| Country | (millions of tonnes) |

Source: FAOSTAT of the United Nations[22] | |

Production

In 2018, global production of mangoes (report includes mangosteens and guavas) was 55.4 million tonnes, led by India with 39% (22 million tonnes) of the world total (see table).[22] China and Thailand were the next largest producers (table).

At the wholesale level, the price of mangoes varies according to the size, the variety, and other factors. The FOB Price reported by the United States Department of Agriculture for all mangoes imported into the US ranged from approximately US$4.60 (average low price) to $5.74 (average high price) per box (4 kg/box) during 2018.[23]

Culinary use

Mangoes are generally sweet, although the taste and texture of the flesh varies across cultivars; some, such as Alphonso, have a soft, pulpy, juicy texture similar to an overripe plum, while others, such as Tommy Atkins, are firmer, like a cantaloupe or avocado, with a fibrous texture.[24]

The skin of unripe, pickled, or cooked mango can be eaten, but it has the potential to cause contact dermatitis of the lips, gingiva, or tongue in susceptible people.[25]

Cuisine

The "hedgehog" style is a form of mango preparation

The "hedgehog" style is a form of mango preparation A glass of mango juice

A glass of mango juice.jpg) Sliced Ataulfo mangoes

Sliced Ataulfo mangoes Mango chutney

Mango chutney

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 250 kJ (60 kcal) |

15 g | |

| Sugars | 13.7 |

| Dietary fiber | 1.6 g |

0.38 g | |

0.82 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 7% 54 μg6% 640 μg23 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 2% 0.028 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 3% 0.038 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 4% 0.669 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 4% 0.197 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 9% 0.119 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 11% 43 μg |

| Choline | 2% 7.6 mg |

| Vitamin C | 44% 36.4 mg |

| Vitamin E | 6% 0.9 mg |

| Vitamin K | 4% 4.2 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 1% 11 mg |

| Iron | 1% 0.16 mg |

| Magnesium | 3% 10 mg |

| Manganese | 3% 0.063 mg |

| Phosphorus | 2% 14 mg |

| Potassium | 4% 168 mg |

| Sodium | 0% 1 mg |

| Zinc | 1% 0.09 mg |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

Mangoes are widely used in cuisine. Sour, unripe mangoes are used in chutneys, pickles,[26] dhals and other side dishes in Bengali cuisine, or may be eaten raw with salt, chili, or soy sauce. A summer drink called aam panna comes from mangoes. Mango pulp made into jelly or cooked with red gram dhal and green chillies may be served with cooked rice. Mango lassi is popular throughout South Asia,[27] prepared by mixing ripe mangoes or mango pulp with buttermilk and sugar. Ripe mangoes are also used to make curries. Aamras is a popular thick juice made of mangoes with sugar or milk, and is consumed with chapatis or pooris. The pulp from ripe mangoes is also used to make jam called mangada. Andhra aavakaaya is a pickle made from raw, unripe, pulpy, and sour mango, mixed with chili powder, fenugreek seeds, mustard powder, salt, and groundnut oil. Mango is also used in Andhra Pradesh to make dahl preparations. Gujaratis use mango to make chunda (a spicy, grated mango delicacy).

Mangoes are used to make murabba (fruit preserves), muramba (a sweet, grated mango delicacy), amchur (dried and powdered unripe mango), and pickles, including a spicy mustard-oil pickle and alcohol. Ripe mangoes are often cut into thin layers, desiccated, folded, and then cut. These bars are similar to dried guava fruit bars available in some countries. The fruit is also added to cereal products such as muesli and oat granola. Mangoes are often prepared charred in Hawaii.

Unripe mango may be eaten with bagoong (especially in the Philippines), fish sauce, vinegar, soy sauce, or with dash of salt (plain or spicy). Dried strips of sweet, ripe mango (sometimes combined with seedless tamarind to form mangorind) are also popular. Mangoes may be used to make juices, mango nectar, and as a flavoring and major ingredient in ice cream and sorbetes.

Mango is used to make juices, smoothies, ice cream, fruit bars, raspados, aguas frescas, pies, and sweet chili sauce, or mixed with chamoy, a sweet and spicy chili paste. It is popular on a stick dipped in hot chili powder and salt or as a main ingredient in fresh fruit combinations. In Central America, mango is either eaten green mixed with salt, vinegar, black pepper, and hot sauce, or ripe in various forms.

Pieces of mango can be mashed and used as a topping on ice cream or blended with milk and ice as milkshakes. Sweet glutinous rice is flavored with coconut, then served with sliced mango as a dessert. In other parts of Southeast Asia, mangoes are pickled with fish sauce and rice vinegar. Green mangoes can be used in mango salad with fish sauce and dried shrimp. Mango with condensed milk may be used as a topping for shaved ice.

Food constituents

Nutrients

The energy value per 100 g (3.5 oz) serving of the common mango is 250 kJ (60 kcal), and that of the apple mango is slightly higher (330 kJ (79 kcal) per 100 g). Fresh mango contains a variety of nutrients (right table), but only vitamin C and folate are in significant amounts of the Daily Value as 44% and 11%, respectively.[28][29]

Phytochemicals

Numerous phytochemicals are present in mango peel and pulp, such as the triterpene, lupeol.[30] Mango peel pigments under study include carotenoids, such as the provitamin A compound, beta-carotene, lutein and alpha-carotene,[31][32] and polyphenols, such as quercetin, kaempferol, gallic acid, caffeic acid, catechins and tannins.[33][34] Mango contains a unique xanthonoid called mangiferin.[35]

Phytochemical and nutrient content appears to vary across mango cultivars.[36] Up to 25 different carotenoids have been isolated from mango pulp, the densest of which was beta-carotene, which accounts for the yellow-orange pigmentation of most mango cultivars.[37] Mango leaves also have significant polyphenol content, including xanthonoids, mangiferin and gallic acid.[38]

The pigment euxanthin, known as Indian yellow, is often thought to be produced from the urine of cattle fed mango leaves; the practice is described as having been outlawed in 1908 because of malnutrition of the cattle and possible urushiol poisoning.[39] This supposed origin of euxanthin appears to rely on a single, anecdotal source, and Indian legal records do not outlaw such a practice.[40]

Flavor

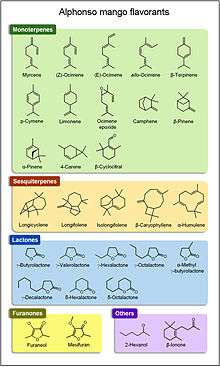

The flavor of mango fruits is conferred by several volatile organic chemicals mainly belonging to terpene, furanone, lactone, and ester classes. Different varieties or cultivars of mangoes can have flavor made up of different volatile chemicals or same volatile chemicals in different quantities.[41] In general, New World mango cultivars are characterized by the dominance of δ-3-carene, a monoterpene flavorant; whereas, high concentration of other monoterpenes such as (Z)-ocimene and myrcene, as well as the presence of lactones and furanones, is the unique feature of Old World cultivars.[42][43][44] In India, 'Alphonso' is one of the most popular cultivars. In 'Alphonso' mango, the lactones and furanones are synthesized during ripening; whereas terpenes and the other flavorants are present in both the developing (immature) and ripening fruits.[45][46][47] Ethylene, a ripening-related hormone well known to be involved in ripening of mango fruits, causes changes in the flavor composition of mango fruits upon exogenous application, as well.[48][49] In contrast to the huge amount of information available on the chemical composition of mango flavor, the biosynthesis of these chemicals has not been studied in depth; only a handful of genes encoding the enzymes of flavor biosynthetic pathways have been characterized to date.[50][51][52][53]

Potential for contact dermatitis

Contact with oils in mango leaves, stems, sap, and skin can cause dermatitis and anaphylaxis in susceptible individuals.[1][25][54] Those with a history of contact dermatitis induced by urushiol (an allergen found in poison ivy, poison oak, or poison sumac) may be most at risk for mango contact dermatitis.[55] Other mango compounds potentially responsible for the dermatitis or allergic reactions include mangiferin.[1] Cross-reactions may occur between mango allergens and urushiol.[56] Sensitized individuals may not be able to safely eat peeled mangos or drink mango juice.[1]

When mango trees are flowering in spring, local people with allergies may experience breathing difficulty, itching of the eyes, or facial swelling, even before flower pollen becomes airborne.[1] In this case, the irritant is likely to be the vaporized essential oil from flowers.[1] During the primary ripening season of mangoes, contact with mango plant parts – primarily sap, leaves and fruit skin[1] – is the most common cause of plant dermatitis in Hawaii.[57]

History

Genetic analysis and comparison of modern mangoes with Paleocene mango leaf fossils found near Damalgiri, Meghalaya indicate that the center of origin of the mango genus was in Indian subcontinent prior to joining of the Indian and Asian continental plates, some 60 million years ago.[58] Mangoes were cultivated in India possibly as early as 2000 BCE.[59] Mango was brought to East Asia around 400–500 BCE, was available by the 14th century on the Swahili Coast,[60] and was brought in the 15th century to the Philippines, and in the 16th century to Brazil by Portuguese explorers.[61]

Mango is mentioned by Hendrik van Rheede, the Dutch commander of the Malabar region in his 1678 book, Hortus Malabaricus, about plants having economic value.[62] When mangoes were first imported to the American colonies in the 17th century, they had to be pickled because of lack of refrigeration. Other fruits were also pickled and came to be called "mangoes", especially bell peppers, and in the 18th century, the word "mango" became a verb meaning "to pickle".[63]

The mango is considered an evolutionary anachronism, whereby seed dispersal was once accomplished by a now-extinct evolutionary forager, such as a megafauna mammal.[64]

Cultural significance

The mango is the national fruit of India,[65][66] Pakistan, and the Philippines. It is also the national tree of Bangladesh.[67][68] In India, harvest and sale of mangoes is during March–May and this is annually covered by news agencies.[19]

The mango has a traditional context in the culture of South Asia. In his edicts, the Mauryan emperor Ashoka references the planting of fruit- and shade-bearing trees along imperial roads:

"On the roads banyan-trees were caused to be planted by me, (in order that) they might afford shade to cattle and men, (and) mango-groves were caused to be planted."

In medieval India, the Indo-Persian poet Amir Khusrow termed the mango "Naghza Tarin Mewa Hindustan" – "the fairest fruit of Hindustan". Mangoes were enjoyed at the court of the Delhi Sultan Alauddin Khijli, and the Mughal Empire was especially fond of the fruits: Babur praises the mango in his Babarnameh, while Sher Shah Suri inaugurated the creation of the Chaunsa variety after his victory over the Mughal emperor Humayun. Mughal patronage to horticulture led to the grafting of thousands of mangoes varieties, including the famous Totapuri, which was the first variety to be exported to Iran and Central Asia. Akbar (1556–1605) is said to have planted a mango orchard of 100,000 trees at Lakhi Bagh in Darbhanga, Bihar,[69] while Jahangir and Shah Jahan ordered the planting of mango-orchards in Lahore and Delhi and the creation of mango-based desserts.[70]

The Jain goddess Ambika is traditionally represented as sitting under a mango tree.[71] Mango blossoms are also used in the worship of the goddess Saraswati. Mango leaves are used to decorate archways and doors in Indian houses and during weddings and celebrations such as Ganesh Chaturthi. Mango motifs and paisleys are widely used in different Indian embroidery styles, and are found in Kashmiri shawls, Kanchipuram and silk sarees. In Tamil Nadu, the mango is referred to as one of the three royal fruits, along with banana and jackfruit, for their sweetness and flavor.[72] This triad of fruits is referred to as ma-pala-vazhai. The classical Sanskrit poet Kālidāsa sang the praises of mangoes.[73]

Mangoes were popularized in China during the Cultural Revolution as symbols of Chairman Mao Zedong's love for the people.[74]

Gallery

A mango tree in full bloom

A mango tree in full bloom- The mango illustrated by Michael Boym in the 1656 book Flora Sinensis

- Most sweet Chaunsa mango from Pakistan

A nearly ripened purple mango, Israel

A nearly ripened purple mango, Israel- Sindhri mango

Shan-e-Khuda, a mango grown in Pakistan

Shan-e-Khuda, a mango grown in Pakistan Banganpalli mangoes in a street market

Banganpalli mangoes in a street market- Mangos in a Paris farmers' market

.jpg) Celebrating Pakistani Mangoes in France

Celebrating Pakistani Mangoes in France

See also

- Achaar, South Asian pickles, commonly containing mango and lime

- Amchoor, mango powder

- Mangifera caesia, a related species also widely cultivated for its fruit in Southeast Asia

- Mangosteen, an unrelated fruit with a similar name

- Mango mealybug

- Mango pickle – Mangai-oorkai (manga-achar), South Indian hot mango pickle

References

- Morton, Julia Frances (1987). Mango. In: Fruits of Warm Climates. NewCROP, New Crop Resource Online Program, Center for New Crops & Plant Products, Purdue University. pp. 221–239. ISBN 978-0-9610184-1-2.

- Kostermans, AJHG; Bompard, JM (1993). The Mangoes: Their Botany, Nomenclature, Horticulture and Utilization. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-421920-5.

- Pangilinan, Jr., Leon (3 October 2014). "In Focus: 9 Facts You May Not Know About Philippine National Symbols". National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- "Mango tree, national tree". 15 November 2010. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- "Mango". Online Etymology Dictionary, Douglas Harper. 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

1580s, from Portuguese manga, from Malay (Austronesian) mangga, from Tamil (Dravidian) mankay, from man "mango tree" + kay "fruit."

- Rocha, Franklin H.; Infante, Francisco; Quilantán, Juan; Goldarazena, Arturo; Funderburk, Joe E. (March 2012). "'Ataulfo' Mango Flowers Contain a Diversity of Thrips (Thysanoptera)". Florida Entomologist. 95 (1): 171–178. doi:10.1653/024.095.0126.

- "Mango". California Rare Fruit Growers. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- "Mango (Mangifera indica) varieties". toptropicals.com. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- Marcos-Filho, Julio. "Physiology of Recalcitrant Seeds" (PDF). Ohio State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2014. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- Ensminger 1995, p. 1373.

- Watson, Andrew J. (1983). Agricultural innovation in the early Islamic world: the diffusion of crops and farming techniques, 700–1100. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 72–3. ISBN 978-0-521-24711-5.

- Jedele, S.; Hau, A.M.; von Oppen, M. "An analysis of the world market for mangoes and its importance for developing countries. Conference on International Agricultural Research for Development, 2003" (PDF).

- "India world's largest producer of mangoes, Rediff India Abroad, 21 April 2004". Rediff.com. 31 December 2004. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- "Mad About mangoes: As exports to the U.S. resume, a juicy business opportunity ripens, India Knowledge@Wharton Network, June 14, 2007". Knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu. 14 June 2007. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- "USAID helps Indian mango farmers access new markets". USAID-India. 3 May 2006. Archived from the original on 1 June 2006.

- "USAID Helps Indian Mango Farmers Access New Markets". Archived from the original on 11 November 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- "actahort.org". actahort.org. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- According to the Oxford Companion to Food

- Jonathan Allen (10 May 2006). "Mango Mania in India". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- Susser, Allen (2001). The Great Mango Book. New York: Ten Speed Press. ISBN 978-1-58008-204-4.

- Mintz C (24 May 2008). "Sweet news: Ataulfos are in season". Toronto Star Online. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Production of mangoes, mangosteens, and guavas in 2018, Crops/Regions/World list/Production Quantity (pick lists)". UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT). 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- National Mango Board. NMB Crop Reports. Accessed 2019-11-24. Average per year of combined values.

- Melissa Clark (1 April 2011). "For everything there is a season, even mangoes". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- Sareen, Richa; Shah, Ashok (2011). "Hypersensitivity manifestations to the fruit mango". Asia Pacific Allergy. 1 (1): 43–9. doi:10.5415/apallergy.2011.1.1.43. ISSN 2233-8276. PMC 3206236. PMID 22053296.

- D.Devika Bal (8 May 1995). "Mango's wide influence in Indian culture". New Strait Times. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- "Vah Chef talking about Mango Lassi's popularity and showing how to make the drink". Vahrehvah.com. 17 November 2016. Archived from the original on 6 August 2013. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- "Nutrient profile for mango from USDA SR-21". Nutritiondata.com. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- "USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, SR-28, Full Report (All Nutrients): 09176, Mangos, raw". National Agricultural Library. USDA. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- Chaturvedi PK, Bhui K, Shukla Y (2008). "Lupeol: connotations for chemoprevention". Cancer Lett. 263 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2008.01.047. PMID 18359153.

- Berardini N, Fezer R, Conrad J, Beifuss U, Carle R, Schieber A (2005). "Screening of mango (Mangifera indica L.) cultivars for their contents of flavonol O – and xanthone C-glycosides, anthocyanins, and pectin". J Agric Food Chem. 53 (5): 1563–70. doi:10.1021/jf0484069. PMID 15740041.

- Gouado I, Schweigert FJ, Ejoh RA, Tchouanguep MF, Camp JV (2007). "Systemic levels of carotenoids from mangoes and papaya consumed in three forms (juice, fresh and dry slice)". Eur J Clin Nutr. 61 (10): 1180–8. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602841. PMID 17637601.

- Mahattanatawee K, Manthey JA, Luzio G, Talcott ST, Goodner K, Baldwin EA (2006). "Total antioxidant activity and fiber content of select Florida-grown tropical fruits". J Agric Food Chem. 54 (19): 7355–63. doi:10.1021/jf060566s. PMID 16968105.

- Singh UP, Singh DP, Singh M, et al. (2004). "Characterization of phenolic compounds in some Indian mango cultivars". Int J Food Sci Nutr. 55 (2): 163–9. doi:10.1080/09637480410001666441. PMID 14985189.

- Andreu GL, Delgado R, Velho JA, Curti C, Vercesi AE (2005). "Mangiferin, a natural occurring glucosyl xanthone, increases susceptibility of rat liver mitochondria to calcium-induced permeability transition". Arch Biochem Biophys. 439 (2): 184–93. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2005.05.015. PMID 15979560.

- Rocha Ribeiro SM, Queiroz JH, Lopes Ribeiro de Queiroz ME, Campos FM, Pinheiro Sant'ana HM (2007). "Antioxidant in mango (Mangifera indica L.) pulp". Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 62 (1): 13–7. doi:10.1007/s11130-006-0035-3. PMID 17243011.

- Chen JP, Tai CY, Chen BH (2004). "Improved liquid chromatographic method for determination of carotenoids in Taiwanese mango (Mangifera indica L.)". J Chromatogr A. 1054 (1–2): 261–8. doi:10.1016/S0021-9673(04)01406-2. PMID 15553152.

- Barreto JC, Trevisan MT, Hull WE, et al. (2008). "Characterization and quantitation of polyphenolic compounds in bark, kernel, leaves, and peel of mango (Mangifera indica L.)". J Agric Food Chem. 56 (14): 5599–610. doi:10.1021/jf800738r. PMID 18558692.

- Source: Kühn. "History of Indian yellow, Pigments Through the Ages". Webexhibits.org. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- Finlay, Victoria (2003). Color: A Natural History of the Palette. New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-8129-7142-2.

- Pandit, Sagar S.; Chidley, Hemangi G.; Kulkarni, Ram S.; Pujari, Keshav H.; Giri, Ashok P.; Gupta, Vidya S. (2009). "Cultivar relationships in mango based on fruit volatile profiles". Food Chemistry. 114: 363–372. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.09.107.

- Pandit SS, Chidley HG, Kulkarni RS, Pujari KH, Giri AP, Gupta VS, 2009, Cultivar relationships in mango based on fruit volatile profiles, Food Chemistry, 144, 363–372.

- Narain N, Bora PS, Narain R and Shaw PE (1998). Mango, In: Tropical and Subtropical Fruits, Edt. by Shaw PE, Chan HT and Nagy S. Agscience, Auburndale, FL, USA, pp. 1–77.

- Kulkarni RS, Chidley HG, Pujari KH, Giri AP and Gupta VS, 2012, Flavor of mango: A pleasant but complex blend of compounds, In Mango Vol. 1: Production and Processing Technology Archived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine (Eds. Sudha G Valavi, K Rajmohan, JN Govil, KV Peter and George Thottappilly) Studium Press LLC.

- Pandit, Sagar S.; Kulkarni, Ram S.; Chidley, Hemangi G.; Giri, Ashok P.; Pujari, Keshav H.; Köllner, Tobias G.; Degenhardt, Jörg; Gershenzon, Jonathan; Gupta, Vidya S. (2009). "Changes in volatile composition during fruit development and ripening of 'Alphonso' mango". Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 89 (12): 2071–2081. doi:10.1002/jsfa.3692.

- Gholap, A. S., Bandyopadhyay, C., 1977. Characterization of green aroma of raw mango (Mangifera indica L.). Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 28, 885–888

- Kulkarni, Ram S.; Chidley, Hemangi G.; Pujari, Keshav H.; Giri, Ashok P.; Gupta, Vidya S. (2012). "Geographic variation in the flavour volatiles of Alphonso mango". Food Chemistry. 130: 58–66. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.06.053.

- Lalel HJD, Singh Z, Tan S, 2003, The role of ethylene in mango fruit aroma volatiles biosynthesis, Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology, 78, 485–496.

- Chidley, Hemangi G.; Kulkarni, Ram S.; Pujari, Keshav H.; Giri, Ashok P.; Gupta, Vidya S. (2013). "Spatial and temporal changes in the volatile profile of Alphonso mango upon exogenous ethylene treatment". Food Chemistry. 136 (2): 585–594. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.08.029. PMID 23122101.

- Pandit, S. S.; Kulkarni, R. S.; Giri, A. P.; Köllner, T. G.; Degenhardt, J.; Gershenzon, J.; Gupta, V. S. (June 2010). "Expression profiling of various genes during the development and ripening of Alphonso mango". Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 48 (6): 426–433. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.02.012. PMID 20363641.

- Singh, Rajesh K.; Sane, Vidhu A.; Misra, Aparna; Ali, Sharique A.; Nath, Pravendra (2010). "Differential expression of the mango alcohol dehydrogenase gene family during ripening". Phytochemistry. 71 (13): 1485–1494. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.05.024. PMID 20598721.

- Kulkarni, Ram; Pandit, Sagar; Chidley, Hemangi; Nagel, Raimund; Schmidt, Axel; Gershenzon, Jonathan; Pujari, Keshav; Giri, Ashok; Gupta, Vidya (2013). "Characterization of three novel isoprenyl diphosphate synthases from the terpenoid rich mango fruit". Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 71: 121–131. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.07.006. PMID 23911730.

- Kulkarni RS, Chidley HG, Deshpande A, Schmidt A, Pujari KH, Giri AP and Gershenzon J, Gupta VS, 2013, An oxidoreductase from ‘Alphonso’ mango catalyzing biosynthesis of furaneol and reduction of reactive carbonyls, SpringerPlus, 2, 494.

- Miell J, Papouchado M, Marshall A (1988). "Anaphylactic reaction after eating a mango". British Medical Journal. 297 (6664): 1639–40. doi:10.1136/bmj.297.6664.1639. PMC 1838873. PMID 3147776.

- Hershko K, Weinberg I, Ingber A (2005). "Exploring the mango – poison ivy connection: the riddle of discriminative plant dermatitis". Contact Dermatitis. 52 (1): 3–5. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2005.00454.x. PMID 15701120.

- Oka K, Saito F, Yasuhara T, Sugimoto A (2004). "A study of cross-reactions between mango contact allergens and urushiol". Contact Dermatitis. 51 (5–6): 292–6. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2004.00451.x. PMID 15606656.

- McGovern TW, LaWarre S (2001). "Botanical briefs: the mango tree—Mangifera indica L.". Cutis. 67 (5): 365–6. PMID 11381849.

- Sherman A, Rubinstein M, Eshed R, Benita M, Ish-Shalom M, Sharabi-Schwager M, Rozen A, Saada D, Cohen Y, Ophir R (November 2015). "Mango (Mangifera indica L.) germplasm diversity based on single nucleotide polymorphisms derived from the transcriptome". BMC Plant Biol. 15: 277. doi:10.1186/s12870-015-0663-6. PMC 4647706. PMID 26573148.

- Sauer, Jonathan D. (1993). Historical geography of crop plants : a select roster. Boca Raton u.a.: CRC Press. p. 17. ISBN 0849389011.

- Ibn Batuta, Said. Hamdun, and Noel Quinton. King. 1994. Ibn Battuta in Black Africa. Princeton: M. Wiener Publishers.

- Gepts, P. (n.d.). "PLB143: Crop of the Day: Mango, Mangifera indica". The evolution of crop plants. Dept. of Plant Sciences, Sect. of Crop & Ecosystem Sciences, University of California, Davis. Archived from the original on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- "Hendrik Adriaan Van Reed Tot Drakestein 1636–1691 and Hortus, Malabaricus". google.co.in. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- Creed, Richard (5 September 2010). "Relative Obscurity: Variations of antigodlin grow". Winston-Salem Journal (Opinion). Retrieved 6 September 2010.

One plausible explanation of the usage [calling a green pepper a mango] is this: Mangos (the real thing) that were imported into the American colonies were from the East Indies. Transport was slow. Refrigeration was not available, so the mangos were pickled for shipment. Because of that, people began referring to any pickled vegetable or fruit as a mango ... bell peppers stuffed with spiced cabbage and pickled ... became so popular that bell peppers, pickled or not, became known as mangos. In the early 18th century, mango became a verb meaning to pickle.

- Spengler, Robert N. (April 2020). "Anthropogenic Seed Dispersal: Rethinking the Origins of Plant Domestication". Trends in Plant Science. 25 (4): 340–348. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2020.01.005.

- "National Fruit". Know India. Government of India. Archived from the original on 20 August 2010. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- "National Fruit".

- "Mango tree, national tree". BDnews24.com. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- "Mango tree, national tree". bdnews24.com.

- Curtis Morgan (18 June 1995). "Mango has a long history as a culinary treat in India". The Milwaukee Journal. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- Sen, Upala (June 2017). "Peeling the Emperor of Fruits". Telegraph India.

- Ambika In Jaina Art And Literature.

- Subrahmanian N, Hikosaka S, Samuel GJ (1997). Tamil social history. p. 88. Retrieved 23 March 2010.

- "His highness, Mango maharaja: An endless obsession – Yahoo! Lifestyle India". In.lifestyle.yahoo.com. 29 May 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- Moore, Malcolm (7 March 2013). "How China came to worship the mango during the Cultural Revolution". Telegraph.co.uk. Additional reporting by Valentina Luo. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

Further reading

- Ensminger, Audrey H.; et al. (1995). The Concise Encyclopedia of Foods & Nutrition. CRC Press. p. 651. ISBN 978-0-8493-4455-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Litz, Richard E. (editor, 2009). The Mango: Botany, Production and Uses. 2nd edition. CABI. ISBN 978-1-84593-489-7.

- Susser, Allen (2001). The Great Mango Book: A Guide with Recipes. Ten Speed Press. ISBN 978-1-58008-204-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikispecies has information related to Mangifera |