Hijab

A hijab (/hɪˈdʒɑːb, hɪˈdʒæb, ˈhɪdʒ.æb, hɛˈdʒɑːb/;[1][2][3][4] Arabic: حجاب, romanized: ḥijāb, pronounced [ħɪˈdʒaːb] in common English usage) is a veil worn by some Muslim women in the presence of any male outside of their immediate family, which usually covers the head and chest. The term can refer to any head, face, or body covering worn by Muslim women that conforms to Islamic standards of modesty. Hijab can also refer to the seclusion of women from men in the public sphere, or it may denote a metaphysical dimension, for example referring to "the veil which separates man or the world from God."[5]

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic female dress |

|---|

| Types |

| Practice and law by country |

| Concepts |

| Other |

In the Qur'an, hadith, and other classical Arabic texts the term khimār (Arabic: خِمار) was used to denote a headscarf, and ḥijāb was used to denote a partition, a curtain, or was used generally for the Islamic rules of modesty and dress for females.[6][7][8][9]

In its traditional form, it is worn by women to maintain modesty and privacy from unrelated males. According to the Encyclopedia of Islam and Muslim World, modesty in the Quran concerns both men's and women's "gaze, gait, garments, and genitalia."[10] The Qur'an instructs Muslim women to dress modestly.[11] Some Islamic legal systems define this type of modest clothing as covering everything except the face and hands up to wrists.[5][12] These guidelines are found in texts of hadith and fiqh developed after the revelation of the Qur'an but, according to some, are derived from the verses (ayahs) referencing hijab in the Qur'an.[10] Some believe that the Qur'an itself does not mandate that women wear hijab.[13][14]

In the Qur'an, the term hijab refers to a partition or curtain in the literal or metaphorical sense. The verse where it is used literally is commonly understood to refer to the curtain separating visitors to Muhammad's house from his wives' lodgings. This had led some to argue that the mandate of the Qur'an to wear hijab applied to the wives of Muhammad, and not women generally.[15][16]

In recent times, wearing hijab in public has been required by law in Iran and the Indonesian province of Aceh. Other countries, both in Europe and in the Muslim world, have passed laws banning some or all types of hijab in public or in certain types of locales. Women in different parts of the world have also experienced unofficial pressure to wear or not wear hijab.

In Islamic scripture

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic culture |

|---|

| Architecture |

| Art |

|

| Dress |

| Holidays |

|

| Literature |

|

| Music |

| Theatre |

|

Quran

The Quran instructs both Muslim men and women to dress in a modest way, but there is disagreement on how these instructions should be interpreted. The verses relating to dress use the terms khimār (head cover) and jilbāb (a dress or cloak) rather than ḥijāb.[7] Of the more than 6,000 verses in the Quran, about half a dozen refer specifically to the way a woman should dress or walk in public.[17]

The clearest verse on the requirement of modest dress is Surah 24:31, telling women to guard their private parts and draw their khimār over their bosoms.[18][19]

And say to the believing women that they should lower their gaze and guard their private parts; that they should not display their beauty and ornaments except what (must ordinarily) appear thereof; that they should draw their khimār over their breasts and not display their beauty except to their husband, their fathers, their husband's fathers, their sons, their husbands' sons, their brothers or their brothers' sons, or their sisters' sons, or their women, or the slaves whom their right hands possess, or male servants free of physical needs, or small children who have no sense of the shame of sex; and that they should not strike their feet in order to draw attention to their hidden ornaments.

In Surah 33:59 Muhammad is commanded to ask his family members and other Muslim women to wear outer garments when they go out, so that they are not harassed:[19]

O Prophet! Enjoin your wives, your daughters, and the wives of true believers that they should cast their outer garments over their persons (when abroad): That is most convenient, that they may be distinguished and not be harassed.

The Islamic commentators generally agree this verse refers to sexual harassment of women of Medina. It is also seen to refer to a free woman, for which Tabari cites Ibn Abbas. Ibn Kathir states that the jilbab distinguishes free Muslim women from those of Jahiliyyah, so other men know they are free women and not slavegirls or whores, indicating covering oneself does not apply to non-Muslims. He cites Sufyan al-Thawri as commenting that while it may be seen as permitting to look upon non-Muslim women who adorn themselves, it is not allowed in order to avoid lust. Al-Qurtubi concurs with Tabari about this ayah being for those who are free. He reports that the correct view is that a jilbab covers the whole body. He also cites the Sahabah as saying it is no longer than a rida (a shawl or a wrapper that covers the upper body). He also reports a minority view which considers the niqab or head-covering as jilbab. Ibn Arabi considered that excessive covering would make it impossible for a woman to be recognised which the verse mentions, though both Qurtubi and Tabari agree that the word recognition is about distinguishing free women.[20]

Some scholars like Ibn Hayyan, Ibn Hazm and Muhammad Nasiruddin al-Albani questioned the ayah's common explanation. Hayyan believed that "believing women" referred to both free women and slaves as the latter are bound to more easily entice lust and their exclusion is not clearly indicated. Hazm too believed that it covered Muslim slaves as it would violate the law of not molesting a slave or fornication with her like that with a free woman. He stated that anything not attributed to Muhammad should be disregarded.[21]

The word ḥijāb in the Quran refers not to women's clothing, but rather a spatial partition or curtain.[7] Sometimes its use is literal, as in the verse which refers to the screen that separated Muhammad's wives from the visitors to his house (33:53), while in other cases the word denotes separation between deity and mortals (42:51), wrongdoers and righteous (7:46, 41:5), believers and unbelievers (17:45), and light from darkness (38:32).[7]

The interpretations of the ḥijāb as separation can be classified into three types: as visual barrier, physical barrier, and ethical barrier. A visual barrier (for example, between Muhammad's family and the surrounding community) serves to hide from sight something, which places emphasis on a symbolic boundary. A physical barrier is used to create a space that provides comfort and privacy for individuals, such as elite women. An ethical barrier, such as the expression purity of hearts in reference to Muhammad's wives and the Muslim men who visit them, makes something forbidden.[17]

Hadith

.jpg)

The hadith sources specify the details of hijab (Islamic rules of dress) for men and women, exegesis of the Qur'anic verses narrated by sahabah, and are a major source which Muslim legal scholars used to derive their rulings.[22][23][24]

- Narrated Umm Salama Hind bint Abi Umayya, Ummul Mu'minin: "When the verse 'That they should cast their outer garments over their persons' was revealed, the women of Ansar came out as if they had crows hanging down over their heads by wearing outer garments." 32:4090. Abū Dawud classed this hadith as authentic.

- Narrated Safiya bint Shaiba: "Aisha used to say: 'When (the Verse): "They should draw their veils (khimaar) over their necks and bosoms (juyyub)," was revealed, (the ladies) cut their waist sheets at the edges and veiled themselves (Arabic: فَاخْتَمَرْنَ, lit. 'to put on a hijab') with the cut pieces.'" Sahih al-Bukhari, 6:60:282, 32:4091. This hadith is often translated as "...and covered their heads and faces with the cut pieces of cloth,"[25] as the Arabic word used in the text (Arabic: فَاخْتَمَرْنَ) could include or exclude the face and there was ikhtilaf on whether covering the face is farḍ, or obligatory. The most prominent sharh, or explanation, of Sahih Bukhari is Fatḥ al-Bārī which states this included the face.

- Yahya related to me from Malik from Muhammad ibn Zayd ibn Qunfudh that his mother asked Umm Salama, the wife of the Prophet, may Allah bless him and grant him peace, "What clothes can a woman wear in prayer?" She said, "She can pray in the khimār (headscarf) and the diri' (Arabic: الدِّرْعِ, lit. 'shield, armature', transl. 'a woman's garment') that reaches down and covers the top of her feet." Muwatta Imam Malik book 8 hadith 37.

- Aishah narrated that Allah's Messenger said: "The Salat (prayer) of a woman who has reached the age of menstruation is not accepted without a khimār." Jami` at-Tirmidhi 377.

Dress code

Sunni

The four major Sunni schools of thought (Hanafi, Shafi'i, Maliki and Hanbali) hold by consensus that it is obligatory for the entire body of the woman (see awrah), except her hands and face (and feet according to Hanafis) to be covered during prayer and in the presence of people of the opposite sex other than close family members (whom one is forbidden to marry—see mahram).[26][27][28] According to Hanafis and other scholars, these requirements extend to being around non-Muslim women as well, for fear that they may describe her physical features to unrelated men.[29]

Men must cover from their belly buttons to their knees, though the schools differ on whether this includes covering the navel and knees or only what is between them.[30][31][32][33]

It is recommended that women wear clothing that is not form fitting to the body, such as modest forms of Western clothing (long shirts and skirts), or the more traditional jilbāb, a high-necked, loose robe that covers the arms and legs. A khimār or shaylah, a scarf or cowl that covers all but the face, is also worn in many different styles.

Some Salafi scholars such as Muhammad ibn al Uthaymeen believe that covering the hands and face for all adult women is obligatory.[34]

Shia

Modern Muslim scholars believe that it is obligatory in Islamic law that men and women abide by the rules of hijab (as outlined in their respective school of thought). These include the Iraqi Shia Marja' (Grand Ayatollah) Ali al-Sistani;[35] the Sunni Permanent Committee for Islamic Research and Issuing Fatwas in Saudi Arabia;[36] and others.[37] In nearly all Muslim cultures, young girls are not required to wear a ħijāb.

.jpg)

The major and most important Shia hadith collections such as Nahj Al-Balagha and Kitab Al-Kafi for the most part do not give any details with regards to hijab requirements, however, in a quotation from Man La Yahduruhu al-Faqih Musa al-Kadhim when enquired by his brother solely makes reference to female hijab requirements during the salat (prayer), stating "She covers her body and head with it then prays. And if her feet protrude from beneath, and she doesn't have the means to prevent that, there is no harm".[38]

Miscellaneous

In private, and in the presence of close relatives (mahrams), rules on dress relax. However, in the presence of the husband, most scholars stress the importance of mutual freedom and pleasure of the husband and wife.[39]

Traditional scholars had differences of opinion on covering the hands and face. The majority adopted the opinion that the face and hands are not part of their nakedness. Some held the opinion that covering the face is recommended if the woman's beauty is so great that it is distracting and causes temptation or public discord.[40]

Quranists

Quranists are Muslims who view the Quran as the primary source of religious stipulation. Among the prerequisites which Quranists procure include the following verses:

O wives of prophet! You are not like other women; if you want to be righteous do not be too soft to make those in whose heart a disease hopeful; and speak in recognised manner. And stay in your homes and make not a dazzling display like that of the former times of ignorance and offer prayer and pay zakah; and obey God and His messenger; o people of (Prophet’s) house! God wants to remove impurity from you and make you clean and pure.

O believers! Do not enter in houses of prophet except if you are permitted for a meal and its readiness is not awaited but when you are invited then enter and when you have eaten disperse and do not linger in conversation; it troubles the prophet and he is shy of you but God is not shy of telling truth; and when ye ask of them [the wives of the Prophet] anything, ask it of them from behind a curtain (hijab) it is purer for you hearts and their hearts; and it is not allowed for you to hurt messenger or marry his wives after him ever; indeed it is great enormity in God’s sight.[41]

Nonetheless, since Quranism overall lacks a formulated and coordinated framework, adherents to its creed overall do not have a unanimous concurrence over how Quranic verses apply, which some Quranist-oriented female Muslims observing the hijab and others not. Rania, the wife of King of Jordan, once took a Quran-centric approach on why she does not observe the hijab, although she has never self-identified as a Quranist.[42]

Alternative views

Some Muslims take a relativist approach to hijab. They believe that the commandment to maintain modesty must be interpreted with regard to the surrounding society. What is considered modest or daring in one society might not be considered so in another. It is important, they say, for believers to wear clothing that communicates modesty and reserve.[43]

Along with scriptural arguments, Leila Ahmed argues that head covering should not be compulsory in Islam because the veil predates the revelation of the Qur'an. Head-covering was introduced into Arabia long before Muhammad, primarily through Arab contacts with Syria and Iran, where the hijab was a sign of social status. After all, only a woman who need not work in the fields could afford to remain secluded and veiled.[15][44]

Ahmed argues for a more liberal approach to hijab. Among her arguments is that while some Qur'anic verses enjoin women in general to "draw their Jilbabs (overgarment or cloak) around them to be recognized as believers and so that no harm will come to them"[Quran 33:58–59] and "guard their private parts ... and drape down khimar over their breasts [when in the presence of unrelated men]",[Quran 24:31] they urge modesty. The word khimar refers to a piece of cloth that covers the head, or headscarf.[45] While the term "hijab" was originally anything that was used to conceal,[46] it became used to refer to concealing garments worn by women outside the house, specifically the headscarf or khimar.[47]

According to at least three authors (Karen Armstrong, Reza Aslan and Leila Ahmed), the stipulations of the hijab were originally meant only for Muhammad's wives, and were intended to maintain their inviolability. This was because Muhammad conducted all religious and civic affairs in the mosque adjacent to his home:

People were constantly coming in and out of this compound at all hours of the day. When delegations from other tribes came to speak with Prophet Muhammad, they would set up their tents for days at a time inside the open courtyard, just a few feet away from the apartments in which Prophet Muhammad's wives slept. And new emigrants who arrived in Yatrib would often stay within the mosque's walls until they could find suitable homes.[15]

According to Ahmed:

By instituting seclusion Prophet Muhammad was creating a distance between his wives and this thronging community on their doorstep.[16]

They argue that the term darabat al-hijab ('taking the veil') was used synonymously and interchangeably with "becoming Prophet Muhammad's wife", and that during Muhammad's life, no other Muslim woman wore the hijab. Aslan suggests that Muslim women started to wear the hijab to emulate Muhammad's wives, who are revered as "Mothers of the Believers" in Islam,[15] and states "there was no tradition of veiling until around 627 C.E." in the Muslim community.[15][16]

Another interpretation differing from the traditional states that a veil is not compulsory in front of blind men and men lacking physical desire (i.e., asexuals and hyposexuals).[48][49][50]

Some scholars think that these contemporary views and arguments, however, contradict the hadith sources, the classical scholars, exegesis sources, historical consensus, and interpretations of the companions (such as Aisha and Abdullah ibn Masud).

Many traditionalist Muslims reject the contemporary views, however, some traditionalist Muslim scholars accept the contemporary views and arguments as those hadith sources are not sahih and ijma would no longer be applicable if it is argued by scholars (even if it is argued by only one scholar). Notable examples of traditionalist Muslim scholars who accept these contemporary views include the Indonesian scholar Buya Hamka.

Contemporary practice

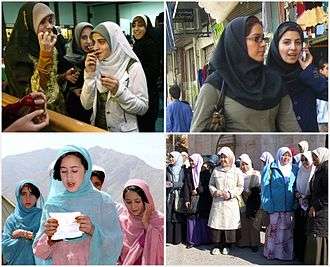

.jpg)

The styles and practices of hijab vary widely across the world due to cultural influences

An opinion poll conducted in 2014 by The University of Michigan's Institute for Social Research asked residents of seven Muslim-majority countries (Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, Tunisia, Turkey, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia) which style of women's dress they considered to be most appropriate in public.[51] The survey found that the headscarf (in its tightly- or loosely-fitting form) was chosen by the majority of respondents in Egypt, Iraq, Tunisia and Turkey.[51] In Saudi Arabia 63% gave preference to the niqab face veil; in Pakistan the niqab, the full-length chador robe and the headscarf, received about a third of the votes each; while in Lebanon half of the respondents in the sample (which included Christians and Druze) opted for no head covering at all.[51][52] The survey found "no significant difference" in the preferences between surveyed men and women, except in Pakistan, where more men favored conservative women's dress.[52] However, women more strongly support women's right to choose how to dress.[52] People with university education are less conservative in their choice than those without one, and more supportive of women's right to decide their dress style, except in Saudi Arabia.[52]

Some fashion-conscious women have been turning to non-traditional forms of hijab such as turbans.[53][54] While some regard turbans as a proper head cover, others argue that it cannot be considered a proper Islamic veil if it leaves the neck exposed.[53]

According to a Pew Research Center survey, among the roughly 1 million Muslim women living in the U.S., 43% regularly wear headscarves, while about a half do not cover their hair.[55] In another Pew Research Center poll (2011), 36% of Muslim American women reported wearing hijab whenever they were in public, with an additional 24% saying they wear it most or some of the time, while 40% said they never wore the headcover.[56]

In Iran, where wearing the hijab is legally required, many women push the boundaries of the state-mandated dress code, risking a fine or a spell in detention.[57] The Iranian president Hassan Rouhani had vowed to rein in the morality police and their presence on the streets has decreased since he took office, but the powerful conservative forces in the country have resisted his efforts, and the dress codes are still being enforced, especially during the summer months.[58]

In Turkey the hijab was formerly banned in private and state universities and schools. The ban applied not to the scarf wrapped around the neck, traditionally worn by Anatolian peasant women, but to the head covering pinned neatly at the sides, called türban in Turkey, which has been adopted by a growing number of educated urban women since the 1980s. As of the mid-2000s, over 60% of Turkish women covered their head outside home, though only 11% wore a türban.[59][60][61][62] The ban was lifted from universities in 2008,[63] from government buildings in 2013,[64] and from schools in 2014.[65]

Burqa and niqab

There are several types of veils which cover the face in part or in full.

The burqa (also spelled burka) is a garment that covers the entire body, including the face.[66] It is commonly associated with the Afghan chadri, whose face-veiling portion is typically a piece of netting that obscures the eyes but allows the wearer to see out.

The niqab is a term which is often incorrectly used interchangeably with burqa.[66] It properly refers to a garment that covers a woman's upper body and face, except for her eyes.[66] It is particularly associated with the style traditionally worn in the Arabian Peninsula, where the veil is attached by one side and covers the face only below the eyes, thereby allowing the eyes to be seen.

Only a minority of Islamic scholars believe that covering the face is mandatory, and the use of niqab beyond its traditional geographic strongholds has been a subject of political controversy.[67][68]

In a 2014 survey of men and women in seven Muslim-majority countries, the Afghan burqa was the preferred form of woman's dress for 11% of respondents in Saudi Arabia, 4% in Iraq, 3% in Pakistan, 2% in Lebanon, and 1% or less in Egypt, Tunisia, and Turkey.[51] The niqab face veil was the preferred option for 63% of respondents in Saudi Arabia, 32% in Pakistan, 9% in Egypt, 8% in Iraq, and 2% or less in Lebanon, Tunisia, and Turkey.[51]

History

Pre-Islamic veiling practices

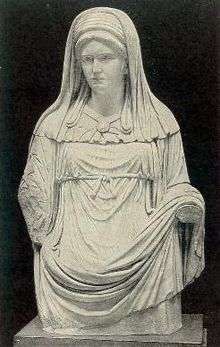

Veiling did not originate with the advent of Islam. Statuettes depicting veiled priestesses precede all major Abrahamic religions (Christianity, Judaism, and Islam), dating back as far as 2500 BCE.[69] Elite women in ancient Mesopotamia and in the Byzantine, Greek, and Persian empires wore the veil as a sign of respectability and high status.[70] In ancient Mesopotamia, Assyria had explicit sumptuary laws detailing which women must veil and which women must not, depending upon the woman's class, rank, and occupation in society.[70] Female slaves and prostitutes were forbidden to veil and faced harsh penalties if they did so.[7] Veiling was thus not only a marker of aristocratic rank, but also served to "differentiate between 'respectable' women and those who were publicly available".[7][70]

Strict seclusion and the veiling of matrons were also customary in ancient Greece. Between 550 and 323 BCE, prior to Christianity, respectable women in classical Greek society were expected to seclude themselves and wear clothing that concealed them from the eyes of strange men.[71]

.jpg)

It is not clear whether the Hebrew Bible contains prescriptions with regard to veiling, but rabbinic literature presents it as a question of modesty (tzniut).[72] Modesty became an important rabbinic virtue in the early Roman period, and it may have been intended to distinguish Jewish women from their non-Jewish counterparts in the Greco-Roman and later in the Babylonian society.[72] According to rabbinical precepts, married Jewish women have to cover their hair. The surviving representations of veiled Jewish women may reflect general Roman customs rather than particular Jewish practices.[72] According to Fadwa El Guindi, at the inception of Christianity, Jewish women were veiling their heads and faces.[7]

There is archeological evidence suggesting that early Christian women in Rome covered their heads.[72] Writings of Tertullian indicate that a number of different customs of dress were associated with different cults to which early Christians belonged around 200 CE.[72] The best known early Christian view on veiling is the passage in 1 Corinthians 11:4-7, which states that "every woman who prays or prophesies with her head uncovered dishonors her head".[72] This view may have been influenced by Roman pagan customs, such as the head covering worn by the priestesses of Vesta (Vestal Virgins), rather than Jewish practices.[72] In turn, the rigid norms pertaining to veiling and seclusion of women found in Christian Byzantine literature have been influenced by ancient Persian traditions, and there is evidence to suggest that they differed significantly from actual practice.[73]

Intermixing of populations resulted in a convergence of the cultural practices of Greek, Persian, and Mesopotamian empires and the Semitic peoples of the Middle East.[7] Veiling and seclusion of women appear to have established themselves among Jews and Christians before spreading to urban Arabs of the upper classes and eventually among the urban masses.[7] In the rural areas it was common to cover the hair, but not the face.[7]

Leila Ahmed argues that "Whatever the cultural source or sources, a fierce misogyny was a distinct ingredient of Mediterranean and eventually Christian thought in the centuries immediately preceding the rise of Islam."[74] Ahmed interprets veiling and segregation of sexes as an expression of a misogynistic view of shamefulness of sex which focused most intensely on shamefulness of the female body and danger of seeing it exposed.[74]

During Muhammad's lifetime

Available evidence suggests that veiling was not introduced into Arabia by Muhammad, but already existed there, particularly in the towns, although it was probably not as widespread as in the neighboring countries such as Syria and Palestine.[75] Similarly to the practice among Greeks, Romans, Jews, and Assyrians, its use was associated with high social status.[75] In the early Islamic texts, term hijab does not distinguish between veiling and seclusion, and can mean either "veil" or "curtain".[76] The only verses in the Qur'an that specifically reference women's clothing are those promoting modesty, instructing women to guard their private parts and wear scarves that fall onto their breast area in the presence of men.[77] The contemporary understanding of the hijab dates back to Hadith when the "verse of the hijab" descended upon the community in 627 CE.[78] Now documented in Sura 33:53, the verse states, "And when you ask [his wives] for something, ask them from behind a partition. That is purer for your hearts and their hearts".[79] This verse, however, was not addressed to women in general, but exclusively to Muhammad's wives. As Muhammad's influence increased, he entertained more and more visitors in the mosque, which was then his home. Often, these visitors stayed the night only feet away from his wives' apartments. It is commonly understood that this verse was intended to protect his wives from these strangers.[80] During Muhammad's lifetime the term for donning the veil, darabat al-hijab, was used interchangeably with "being Muhammad's wife".[75]

Later pre-modern history

The practice of veiling was borrowed from the elites of the Byzantine and Persian empires, where it was a symbol of respectability and high social status, during the Arab conquests of those empires.[81] Reza Aslan argues that "The veil was neither compulsory nor widely adopted until generations after Muhammad's death, when a large body of male scriptural and legal scholars began using their religious and political authority to regain the dominance they had lost in society as a result of the Prophet's egalitarian reforms".[80]

Because Islam identified with the monotheistic religions of the conquered empires, the practice was adopted as an appropriate expression of Qur'anic ideals regarding modesty and piety.[82] Veiling gradually spread to upper-class Arab women, and eventually it became widespread among Muslim women in cities throughout the Middle East. Veiling of Arab Muslim women became especially pervasive under Ottoman rule as a mark of rank and exclusive lifestyle, and Istanbul of the 17th century witnessed differentiated dress styles that reflected geographical and occupational identities.[7] Women in rural areas were much slower to adopt veiling because the garments interfered with their work in the fields.[83] Since wearing a veil was impractical for working women, "a veiled woman silently announced that her husband was rich enough to keep her idle."[84]

By the 19th century, upper-class urban Muslim and Christian women in Egypt wore a garment which included a head cover and a burqa (muslin cloth that covered the lower nose and the mouth).[7] The name of this garment, harabah, derives from early Christian and Judaic religious vocabulary, which may indicate the origins of the garment itself.[7] Up to the first half of the twentieth century, rural women in the Maghreb and Egypt put on a form of niqab when they visited urban areas, "as a sign of civilization".[85]

Modern history

.jpg)

Western clothing largely dominated in Muslim countries the 1960s and 1970s.[86][87] For example, in Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran, many liberal women wore short skirts, flower printed hippie dresses, flared trousers,[88] and went out in public without the hijab. This changed following the Soviet–Afghan War, military dictatorship in Pakistan, and Iranian revolution of 1979, when traditional conservative attire including the abaya, jilbab and niqab made a comeback.[89][90] There were demonstrations in Iran in March 1979, after the hijab law was brought in, decreeing that women in Iran would have to wear scarves to leave the house.[91] However, this phenomenon did not happen in all countries with a significant Muslim population, in countries such as Turkey, there has been a decline on women wearing the hijab in recent years.,[92] although under Erdoğan Turkey is becoming more conservative and Islamic, as Turkey repeals the Atatürk-era hijab,[93][94] and the founding of new fashion companies catering to women who want to dress more conservatively.[95]

In 1953, Egyptian leader President Gamal Abdel Nasser claims that he was told by the leader of the Muslim Brotherhood organization that they wanted to enforce the wearing of the hijab, to which Nasser responded, "Sir, I know you have a daughter in college, and she doesn't wear a headscarf or anything! Why don't you make her wear the headscarf? So you can't make one girl, your own daughter, wear it, and yet you want me to go and make ten million women wear it?"

The late-twentieth century saw a resurgence of the hijab in Egypt after a long period of decline as a result of westernization. Already in the mid-1970s some college aged Muslim men and women began a movement meant to reunite and rededicate themselves to the Islamic faith.[96][97] This movement was named the Sahwah,[98] or awakening, and sparked a period of heightened religiosity that began to be reflected in the dress code.[96] The uniform adopted by the young female pioneers of this movement was named al-Islāmī (Islamic dress) and was made up of an "al-jilbāb—an unfitted, long-sleeved, ankle-length gown in austere solid colors and thick opaque fabric—and al-khimār, a head cover resembling a nun's wimple that covers the hair low to the forehead, comes under the chin to conceal the neck, and falls down over the chest and back".[96] In addition to the basic garments that were mostly universal within the movement, additional measures of modesty could be taken depending on how conservative the followers wished to be. Some women choose to also utilize a face covering (al-niqāb) that leaves only eye slits for sight, as well as both gloves and socks in order to reveal no visible skin.

Soon this movement expanded outside of the youth realm and became a more widespread Muslim practice. Women viewed this way of dress as a way to both publicly announce their religious beliefs as well as a way to simultaneously reject western influences of dress and culture that were prevalent at the time. Despite many criticisms of the practice of hijab being oppressive and detrimental to women's equality,[97] many Muslim women view the way of dress to be a positive thing. It is seen as a way to avoid harassment and unwanted sexual advances in public and works to desexualize women in the public sphere in order to instead allow them to enjoy equal rights of complete legal, economic, and political status. This modesty was not only demonstrated by their chosen way of dress but also by their serious demeanor which worked to show their dedication to modesty and Islamic beliefs.[96]

Controversy erupted over the practice. Many people, both men and women from backgrounds of both Islamic and non-Islamic faith questioned the hijab and what it stood for in terms of women and their rights. There was questioning of whether in practice the hijab was truly a female choice or if women were being coerced or pressured into wearing it.[96] Many instances, such as the Islamic Republic of Iran's current policy of forced veiling for women, have brought these issues to the forefront and generated great debate from both scholars and everyday people.

As the awakening movement gained momentum, its goals matured and shifted from promoting modesty towards more of a political stance in terms of retaining support for Pan-Islamism and a symbolic rejection of Western culture and norms. Today the hijab means many different things for different people. For Islamic women who choose to wear the hijab it allows them to retain their modesty, morals and freedom of choice.[97] They choose to cover because they believe it is liberating and allows them to avoid harassment. Many people (both Muslim and non-Muslim) are against the wearing of the hijab and argue that the hijab causes issues with gender relations, works to silence and repress women both physically and metaphorically, and have many other problems with the practice. This difference in opinions has generated a plethora of discussion on the subject, both emotional and academic, which continues today.

Ever since 11 September 2001, the discussion and discourse on the hijab has intensified. Many nations have attempted to put restrictions on the hijab, which has led to a new wave of rebellion by women who instead turn to covering and wearing the hijab in even greater numbers.[97][100]

Iran

In Iran women act to transform the hijab by challenging the regime subsequently reinventing culture and women's identity within Iran. The female Iranian fashion designer, Naghmeh Kiumarsi, challenges the regime's notion of culture through publicly designing, marketing, and selling clothing pieces that feature tight fitting jeans, and a “skimpy” headscarf.[101] Kiumarsi embodies her own notion of culture and identity and utilizes fashion to value the differences among Iranian women, as opposed to a single identity under the Islamic dress code and welcomes the evolution of Iranian culture with the emergence of new style choices and fashion trends.

Women's resistance in Iran is gaining traction as an increasing number of women challenge the mandatory wearing of the hijab. Smith (2017) addressed the progress that Iranian women have made in her article, “Iran surprises by realizing Islamic dress code for women,”[102] published by The Times, a reputable news organization based in the UK. The Iranian government has enforced their penal dress codes less strictly and instead of imprisonment as a punishment have implemented mandatory reform classes in the liberal capital, Tehran. General Hossein Rahimi, the Tehran's police chief stated, “Those who do not observe the Islamic dress code will no longer be taken to detention centers, nor will judicial cases be filed against them” (Smith, 2017). The remarks of Tehran's recent police chief in 2017 reflect political progress in contrast with the remarks of Tehran's 2006 police chief.[102][103] Iranian women activists have made a headway since 1979 relying on fashion to enact cultural and political change.

Academic studies on the hijab

Although the field is quite new, several academic studies on the hijab have been conducted, and there is growing body of research. It is hypothesized that the beneficial mental health effects of the hijab is due to religiosity rather than the article of clothing itself, and the hijab acts as a proxy for religiosity,[104] but it's also possible use of the hijab may protect Muslim women from appearance-based public scrutiny.[105]

Canada

Muslim women who dressed more modestly were more secure about their body image, and less likely to be pressured by Western media beauty standards. Whereas Muslim women who did not wear hijabs and wore Western clothing were more insecure about their body. Non-Western cultures in the Middle East and Asia, which were incompatible with Islamic values, such as not properly wearing a hijab as is Islamically prescribed, also resulted in similar insecurity as wearing Western clothing.[104]

On the question of the hijab being a "symbol of female oppression", findings from Montreal[106] finds that much of this is baseless and often the result of hypersexualized Western culture trying to deny Muslim women, who do not wish to be sexualized and objectified, their voices. One Muslim woman interviewed states that "I find that Québec women are like [sex] symbols. They are used to sell stuff: toilet paper, cell phones, etc. In school, girls want to impress boys. To get men’s attention, they’re gonna dress sexy. There’s no end to it. It’s a form of submissiveness!"[106] The hijab is viewed by Muslim women as a symbol of cultural resistance to Western imperialism.

United States

In a study comparing Muslim women with non-Muslim women, Muslim women wearing conservative Islamic clothing (i.e., hijabs/abayas) had higher self-esteem, better body image, healthier body weight, felt less sexually objectified, and more respected, compared to non-Muslim Western women who wore Western clothing. Women who wore more conservative Islamic clothing felt less pressure to have an unhealthy thinner body, as well as in reality had a much healthier BMI on the more thinner side. Muslim women who wore Western clothing felt similar "thin-ideal" pressure as non-Muslim women.[107]

Wearing hijab and more conservative Islamic clothing resulted in lower rates of sexual objectification and sexual harassment. Wearing hijabs was negatively correlated with reports of sexual harassment.[108] Men report being more uncomfortable approaching women who wore hijabs or niqabs.[109] This concurred with the Islamic reasons and the reason many Muslim women also give for wearing hijab, aside from God commanding them.[108]

It was found that despite some feminists attempting to speak for Muslim women to claim that Islam and the hijab is "oppressive", such narratives fails to take into account the voices of some real Muslim women. When surveyed, Muslim women contradicted myths about the hijab, and argued that Islam protects them.[110]

Australia

Another study comparing Muslim and non-Muslim women, finds that Islamic values such as wearing more modest clothing protects a Muslim woman's body image and mental health from unrealistic Western beauty standards. More religiosity was correlated to lower body dissatisfaction, sexual objectification, and less eating disorders.[105]

Britain

Other findings show effects appear to be driven by the hijab specifically, rather than religiosity, which was a significant covariate. The use of the hijab, results in more positive body image, less fixation with appearance, and less reliance on Western media beauty standards.[111]

France

A replication of these studies in a French setting finds Muslim women who wore the hijab reported lower weight discrepancy, body dissatisfaction, drive for thinness, and pressure to conform to Western media beauty standards. The effects are attributed to use of the hijab specifically, even after controlling for religiosity. The authors conclude that in the absence of data to the contrary, lawmakers should not rush to demonize the hijab, and should highlight the positive mental health effects of the hijab.[112]

Turkey

The first study done in a Muslim majority country; finds that both the hijab (the clothing itself) and religiosity are both major factors in of themselves, in contributing to positive body image. Muslim women with high religiosity but who did not wear the hijab had higher rates of social appearance anxiety, whereas Muslim women with both high religiosity and wore a hijab did not. Confirming previous findings that these effects persist regardless of nationality or culture.[113]

Compulsion and pressure

Some governments encourage and even oblige women to wear the hijab, while others have banned it in at least some public settings. In many parts of the world women also experience informal pressure for or against wearing hijab, including physical attacks.

Legal enforcement

Iran went from banning all types of veils in 1936, to making Islamic dress mandatory for women following the Islamic Revolution in 1979.[114] In April 1980, it was decided that women in government offices and educational institutions would be mandated to veil.[114] The 1983 penal code prescribed punishment of 74 lashes for women appearing in public without Islamic hijab (hijab shar'ee), leaving the definition of proper hijab ambiguous.[115][116] The same period witnessed tensions around the definition of proper hijab, which sometimes resulted in vigilante harassment of women who were perceived to wear improper clothing.[114][115] In 1984, Tehran's public prosecutor announced that a stricter dress-code should be observed in public establishments, while clothing in other places should correspond to standards observed by the majority of the people.[114] A new regulation issued in 1988 by the Ministry of the Interior based on the 1983 law further specified what constituted violations of hijab.[117] Iran's current penal code stipulates a fine or 10 days to two months in prison as punishment for failure to observe hijab in public, without specifying its form.[118][119] The dress code has been subject of alternating periods of relatively strict and relaxed enforcement over the years, with many women pushing its boundaries, and its compulsory aspect has been a point of contention between conservatives and the current president Hassan Rouhani.[118][120][121] The United Nations Human Rights Council recently called on Iran to guarantee the rights of those human rights defenders and lawyers supporting anti-hijab protests.[122] In governmental and religious institutions, the dress code requires khimar-type headscarf and overcoat, while in other public places women commonly wear a loosely tied headscarf (rousari). The Iranian government endorses and officially promotes stricter types of veiling, praising it by invoking both Islamic religious principles and pre-Islamic Iranian culture.[123]

The Indonesian province of Aceh requires Muslim women to wear hijab in public.[124] Indonesia's central government granted Aceh's religious leaders the right to impose Sharia in 2001, in a deal aiming to put an end to the separatist movement in the province.[124]

In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the dress code used to legally require women, local and foreign, to wear an abaya, a garment that covers the body and arms in public.[125][126] According to most Salafi scholars, a woman is to cover her entire body, including her face and hands, in front of unrelated men. Hence, the vast majority of traditional Saudi women are expected to cover their body and hair in public.[127][128][129][130][131] The Saudi niqab usually leaves a long open slot for the eyes; the slot is held together by a string or narrow strip of cloth.[132] It is widely believed that the abaya is increasingly becoming more of a fashion statement in Saudi Arabia than a religious one with Saudi women wearing colorful, stylish Abayas along with western-style clothing.[133] Women in Saudi Arabia are not legally required to wear headcover or the black abaya – the loose-fitting, full-length robes symbolic of Islamic piety – as long as their attire is "decent and respectful", the kingdom's reform-minded crown prince said.[134]

Legal bans

Muslim world

The tradition of veiling hair in Iranian culture has ancient pre-Islamic origins,[135] but the widespread custom was forcibly ended by Reza Shah's regime in 1936, as he claimed hijab to be incompatible with his modernizing ambitions and ordered "unveiling" act or Kashf-e hijab. The police arrested women who wore the veil and would forcibly remove it, and these policies outraged the Shi'a clerics, and ordinary men and women, to whom appearing in public without their cover was tantamount to nakedness. Many women refused to leave the house out of fear of being assaulted by Reza Shah's police.[136] In 1941, the compulsory element in the policy of unveiling was abandoned.

Turkey had a ban on headscarves at universities until recently. In 2008, the Turkish government attempted to lift a ban on Muslim headscarves at universities, but were overturned by the country's Constitutional Court.[137] In December 2010, however, the Turkish government ended the headscarf ban in universities, government buildings and schools.[138]

In Tunisia, women were banned from wearing hijab in state offices in 1981 and in the 1980s and 1990s, more restrictions were put in place.[139] In 2017, Tajikistan banned hijabs. Minister of Culture, Shamsiddin Orumbekzoda, told Radio Free Europe Islamic dress was "really dangerous". Under existing laws, women wearing hijabs are already banned from entering the country's government offices.[140][141]

Europe

On 15 March 2004, France passed a law banning "symbols or clothes through which students conspicuously display their religious affiliation" in public primary schools, middle schools, and secondary schools. In the Belgian city of Maaseik, the niqāb has been banned since 2006.[142] On 13 July 2010, France's lower house of parliament overwhelmingly approved a bill that would ban wearing the Islamic full veil in public. It became the first European country to ban the full-face veil in public places,[143] followed by Belgium, Latvia, Bulgaria, Austria, Denmark and some cantons of Switzerland in the following years.

Belgium banned the full-face veil in 2011 in places like parks and on the streets. In September 2013, the electors of the Swiss canton of Ticino voted in favour of a ban on face veils in public areas.[144] In 2016, Latvia and Bulgaria banned the burqa in public places.[145][146] In October 2017, wearing a face veil became also illegal in Austria. This ban also includes scarves, masks and clown paint that cover faces to avoid discriminating against Muslim dress.[143] In 2016, Bosnia-Herzegovina's supervising judicial authority upheld a ban on wearing Islamic headscarves in courts and legal institutions, despite protests from the Muslim community that constitutes 40% of the country.[147][148] In 2017, the European Court of Justice ruled that companies were allowed to bar employees from wearing visible religious symbols, including the hijab. However, if the company has no policy regarding the wearing of clothes that demonstrate religious and political ideas, a customer cannot ask employees to remove the clothing item.[149] In 2018, Danish parliament passed a law banning the full-face veil in public places.[150]

In 2016, more than 20 French towns banned the use of the burqini, a style of swimwear intended to accord with rules of hijab.[151][152][153] Dozens of women were subsequently issued fines, with some tickets citing not wearing "an outfit respecting good morals and secularism", and some were verbally attacked by bystanders when they were confronted by the police.[151][154][155][156] Enforcement of the ban also hit beachgoers wearing a wide range of modest attire besides the burqini.[151][156] Media reported that in one case the police forced a woman to remove part of her clothing on a beach in Nice.[154][155][156] The Nice mayor's office denied that she was forced to do so and the mayor condemned what he called the "unacceptable provocation" of wearing such clothes in the aftermath of the Nice terrorist attack.[151][156]

A team of psychologists in Belgium have investigated, in two studies of 166 and 147 participants, whether the Belgians' discomfort with the Islamic hijab, and the support of its ban from the country's public sphere, is motivated by the defense of the values of autonomy and universalism (which includes equality), or by xenophobia/ethnic prejudice and by anti-religious sentiments. The studies have revealed the effects of subtle prejudice/racism, values (self-enhancement values and security versus universalism), and religious attitudes (literal anti-religious thinking versus spirituality), in predicting greater levels of anti-veil attitudes beyond the effects of other related variables such as age and political conservatism.[157]

In 2019, Austria banned the hijab in schools for children up to ten years of age. The ban was motivated by the equality between men and women and improving social integration with respect to local customs. Parents who send their child to school with a headscarf will be fined 440 euro.[158]

In 2019, Staffanstorp Municipality in Sweden banned all veils for school pupils up to sixth grade.[159]

Unofficial pressure to wear hijab

Muslim girls and women have fallen victim to honor killings in both the Western world and elsewhere for refusing to wearing the hijab or for wearing it in way considered to be improper by the perpetrators.[160]

Successful informal coercion of women by sectors of society to wear hijab has been reported in Gaza where Mujama' al-Islami, the predecessor of Hamas, reportedly used "a mixture of consent and coercion" to "'restore' hijab" on urban educated women in Gaza in the late 1970s and 1980s.[161]

Similar behaviour was displayed by Hamas itself during the First Intifada in Palestine. Though a relatively small movement at this time, Hamas exploited the political vacuum left by perceived failures in strategy by the Palestinian factions to call for a "return" to Islam as a path to success, a campaign that focused on the role of women.[162] Hamas campaigned for the wearing of the hijab alongside other measures, including insisting women stay at home, segregation from men and the promotion of polygamy. In the course of this campaign women who chose not to wear the hijab were verbally and physically harassed, with the result that the hijab was being worn "just to avoid problems on the streets".[163]

Wearing of the hijab was enforced by the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. The Taliban required women to cover not only their head but their face as well, because "the face of a woman is a source of corruption" for men not related to them.[164]

In Srinagar, the capital of Indian-administered Kashmir, a previously unknown militant group calling itself Lashkar-e-Jabbar claimed responsibility for a series of acid attacks on women who did not wear the burqa in 2001, threatening to punish women who do not adhere to their vision of Islamic dress. Women of Kashmir, most of whom are not fully veiled, defied the warning, and the attacks were condemned by prominent militant and separatist groups of the region.[165][166]

In 2006, radicals in Gaza have been accused of attacking or threatening to attack the faces of women in an effort to intimidate them from wearing allegedly immodest dress.[168]

In 2014 the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant was reported to have executed several women for not wearing niqab with gloves.[169]

In April 2019 in Norway, telecom company Telia received bomb threats after featuring a Muslim woman taking off her hijab in a commercial. Although the police did not evaluate the threat likely to be carried out, delivering threats is still a crime in Norway.[170]

Unofficial pressure against wearing hijab

In recent years, women wearing hijab have been subject of verbal and physical attacks in Western countries, particularly following terrorist attacks.[171][172][173][174] Louis A. Cainkar writes that the data suggest that women in hijab rather than men are the predominant target of anti-Muslim attacks not because they are more easily identifiable as Muslims, but because they are seen to represent a threat to the local moral order that the attackers are seeking to defend.[172] Some women stop wearing hijab out of fear or following perceived pressure from their acquaintances, but many refuse to stop wearing it out of religious conviction even when they are urged to do so for self-protection.[172]

Kazakhstan has no official ban on wearing hijab, but those who wear it have reported that authorities use a number of tactics to discriminate against them.[175]

In 2015, authorities in Uzbekistan organized a "deveiling" campaign in the capital city Tashkent, during which women wearing hijab were detained and taken to a police station. Those who agreed to remove their hijab were released "after a conversation", while those who refused were transferred to the counterterrorism department and given a lecture. Their husbands or fathers were then summoned to convince the women to obey the police. This followed an earlier campaign in the Fergana Valley.[176]

In 2016 in Kyrgyzstan, the government has sponsored street banners aiming to dissuade women from wearing the hijab.[177]

Workplace discrimination against hijab-wearing women

The issue of discrimination of Muslims is more prevalent among Muslim women due to the hijab being an observable declaration of faith. Particularly after the September 11 attacks and the coining of the term Islamophobia, some of Islamophobia's manifestations are seen within the workplace.[178] Women wearing the hijab are at risk of discrimination in their workplace because the hijab helps identify them for anyone who may hold Islamophobic attitudes.[179][180] Their association with the Islamic faith automatically projects any negative stereotyping of the religion onto them.[181] As a result of the heightened discrimination, some Muslim women in the workplace resort to taking off their hijab in hopes to prevent any further prejudice acts.[182]

A number of Muslim women who were interviewed expressed that perceived discrimination also poses a problem for them.[183] To be specific, Muslim women shared that they chose not to wear the headscarf out of fear of future discrimination.[183]

The discrimination Muslim women face goes beyond affecting their work experience, it also interferes with their decision to uphold religious obligations. In result of discrimination Muslim women in the United States have worries regarding their ability to follow their religion because it might mean they are rejected employment.[184] Ali, Yamada, and Mahmoud (2015)[185] state that women of color who also follow the religion of Islam are considered to be in what is called “triple jeopardy”, due to being a part of two minority groups subject to discrimination.

Ali et al. (2015)[185] study found a relationship between the discrimination Muslims face at work and their job satisfaction. In other words, the discrimination Muslim women face at work is associated with their overall feeling of contentment of their jobs, especially compared to other religious groups.[186]

Muslim women not only experience discrimination whilst in their job environment, they also experience discrimination in their attempts to get a job. An experimental study conducted on potential hiring discrimination among Muslims found that in terms of overt discrimination there were no differences between Muslim women who wore traditional Islamic clothing and those who did not. However, covert discrimination was noted towards Muslim who wore the hijab, and as a result were dealt with in a hostile and rude manner.[187] While observing hiring practices among 4,000 employers in the U.S, experimenters found that employers who self-identified as Republican tended to avoid making interviews with candidates who appeared Muslim on their social network pages.[188]

One instance that some view as hijab discrimination in the workplace that gained public attention and made it to the Supreme Court was EEOC v. Abercrombie & Fitch. The U.S Equal Employment Opportunity Commission took advantage of its power granted by Title VII and made a case for a young hijabi female who applied for a job, but was rejected due to her wearing a headscarf which violated Abercrombie & Fitch's pre-existing and longstanding policy against head coverings and all black garments.[189]

Discrimination levels differ depending on geographical location; for example, South Asian Muslims in the United Arab Emirates do not perceive as much discrimination as their South Asian counterparts in the U.S.[190] Although, South Asian Muslim women in both locations are similar in describing discrimination experiences as subtle and indirect interactions.[190] The same study also reports differences among South Asian Muslim women who wear the hijab, and those who do not. For non-hijabis, they reported to have experienced more perceived discrimination when they were around other Muslims.[190]

Perceived discrimination is detrimental to well-being, both mentally and physically.[191] However, perceived discrimination may also be related to more positive well-being for the individual.[192] A study in New Zealand concluded that while Muslim women who wore the headscarf did in fact experience discrimination, these negative experiences were overcome by much higher feelings of religious pride, belonging, and centrality.[192]

See also

- Merve Kavakçı

- Islam and clothing

- List of religious headgear

- Types of hijab

- Women in Islam

- Kashf-e hijab

- Islamic scarf controversy in France

- Covering variants

- Non-Muslim

- Christian headcovering

- Religious habit

- Tichel

- Tzniut

Notes

- "Definition of hijab in Oxford Dictionaries (British & World English)". Oxforddictionaries.com. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- "Hijab – Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary". Merriam-webster.com. 31 August 2012. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- "Hijab noun – definition in British English Dictionary & Thesaurus – Cambridge Dictionary Online". Dictionary.cambridge.org. 16 April 2013. Archived from the original on 24 June 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- "Definition of hijab". Collins English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- Glasse, Cyril, The New Encyclopedia of Islam, Altamira Press, 2001, p.179-180

- Lane's Lexicon page 519 and 812

- El Guindi, Fadwa; Sherifa Zahur (2009). Hijab. The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195305135.001.0001. ISBN 9780195305135.

- Contemporary Fatwas by Sheik Yusuf Al Qaradawi, vol. 1, pp. 453-455

- Ruh Al Ma’ani by Shihaab Adeen Abi Athanaa’, vol. 18, pp. 309, 313

- Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World (2003), p. 721, New York: Macmillan Reference USA

- Martin et al. (2003), Encyclopedia of Islam & the Muslim World, Macmillan Reference, ISBN 978-0028656038

- Fisher, Mary Pat. Living Religions. New Jersey: Pearson Education, 2008.

- "Irfi.org". Archived from the original on 21 December 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- "Moroccoworldnews.com". Archived from the original on 27 December 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- Aslan, Reza, No God but God, Random House, (2005), p.65–6

- Ahmed, Leila (1992). Women and Gender in Islam: Historical Roots of a Modern Debate. ISBN 9780300055832. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- Bucar, Elizabeth, The Islamic Veil. Oxford, England: Oneworld Publications, 2012.

- Evidence in the Qur'an for Covering Women's Hair, IslamOnline.

- Hameed, Shahul. "Is Hijab a Qur’anic Commandment?," IslamOnline.net. 9 October 2003.

- Islam and the Veil: Theoretical and Regional Contexts, page 111-113]

- Islam and the Veil: Theoretical and Regional Contexts, page 114]

- "Hijab: Fard (Obligation) or Fiction?". virtualmosque.com. 15 October 2012. Archived from the original on 9 November 2018. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- "How Should We Understand the Obligation of Khimar (Head Covering)?". seekershub.org. 25 September 2017. Archived from the original on 8 November 2018. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- Kamali, Mohammad (2005). Principles of Islamic Jurisprudence (3 ed.). Islamic Texts Society. p. 63. ISBN 0946621810. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 November 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 February 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Hsu, Shiu-Sian. "Modesty." Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an. Ed. Jane McAuliffe. Vol. 3. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishers, 2003. 403-405. 6 vols.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 14 February 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- al-Sistani, Ali. "Question & Answer » Hijab (Islamic Dress)". The Official Website of the Office of His Eminence Al-Sayyid Ali Al-Husseini Al-Sistani. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- "Fatwas of the Permanent Committee: Women covering their faces and hands". General Presidency of Scholarly Research and Ifta'. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Archived from the original on 7 November 2018. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Rispler-Chaim, Vardit. "The siwāk: A Medieval Islamic Contribution to Dental Care." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 2.1 (1992): 13-20.

- Heba G. Kotb M.D., Sexuality in Islam, PhD Thesis, Maimonides University, 2004

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Quran Surah Al-Ahzaab ( Verse 53 )". Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- Volk, Anthony. "Islam and Liberalism: Conflicting Values?." Harvard International Review 36.4 (2015): 14.

- Syed, Ibrahim B. (2001). "Women in Islam: Hijab".

- Ahmed, Leila (1992). Women and Gender in Islam: Historical Roots of a Modern Debate. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300055832.

- V.A. Mohamad Ashrof (2005). Islam and gender justice. Gyan Books, 2005. p. 130. ISBN 9788178354569. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- Asma Afsaruddin; A. H. Mathias Zahniser (1997). Humanism, culture, and language in the Near East. Eisenbrauns, 1997. p. 87. ISBN 9781575060200. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- Asma Afsaruddin; A. H. Mathias Zahniser (1997). Humanism, culture, and language in the Near East. Eisenbrauns, 1997. p. 95. ISBN 9781575060200. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- "Is it ok to take off the kimar and niqab in front of a blind man?". Islamqa.info. Archived from the original on 5 September 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- Women revealing their adornment to men who lack physical desire Archived 27 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine retrieved 25 June 2012

- Queer Spiritual Spaces: Sexuality and Sacred Places – Page 89, Kath Browne, Sally Munt, Andrew K. T. Yip - 2010

- "Female Muslim Dress Survey Reveals Wide Range Of Preferences On Hijab, Burqa, Niqab, And More". Huffington Post. 23 January 2014. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- RICH MORIN (14 January 2014). "Q&A with author of U. Mich. study on preferred dress for women in Muslim countries". Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- Shounaz Meky (9 October 2014). "Under wraps: Style savvy Muslim women turn to turbans". Al Arabiya. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- Yasmin Nouh (11 May 2016). "The Beautiful Reasons Why These Women Love Wearing A Hijab". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 10 September 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- "Lifting The Veil: Muslim Women Explain Their Choice". NPR. 21 April 2011. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- "Muslim Americans: No Signs of Growth in Alienation or Support for Extremism; Section 2: Religious Beliefs and Practices". Pew Research Center. 30 August 2011. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- "Playing cat and mouse with Iran′s morality police". Qantara.de. Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- Yara Elmjouie (19 June 2014). "Iran's morality police: patrolling the streets by stealth". Tehran Bureau/The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- Rainsford, Sarah (7 November 2006). "Headscarf issue challenges Turkey". BBC News. Archived from the original on 20 April 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- Rainsford, Sarah (2 October 2007). "Women condemn Turkey constitution". BBC News. Archived from the original on 13 August 2008. Retrieved 4 August 2008.

- Jonathan Head (31 December 2010). "Quiet end to Turkey's college headscarf ban". BBC News. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- Clark-Flory, Tracy (23 April 2007). "Head scarves to topple secular Turkey?". Salon. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 4 August 2008.

- Ayman, Zehra; Knickmeyer, Ellen. Ban on Head Scarves Voted Out in Turkey: Parliament Lifts 80-Year-Old Restriction on University Attire Archived 19 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Washington Post. 10 February 2008. Page A17.

- "Turkey Lifts Longtime Ban on Head Scarves in State Offices". NY Times. 8 October 2013. Archived from the original on 5 December 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- "Turkey-lifts-ban-on-headscarves-at-high-schools". news24.com/. 23 September 2014. Archived from the original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- "From hijab to burqa - a guide to Muslim headwear". Channel 4 News. 24 October 2013. Archived from the original on 5 September 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- "Niqab". BBC. Archived from the original on 12 December 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- "The Islamic veil across Europe". BBC News. 1 July 2014. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- Kahf, Mohja (2008). From Royal Body the Robe was Removed: The Blessings of the Veil and the Trauma of Forced Unveiling in the Middle East. University of California Press. p. 27.

- Ahmed, Leila (1992). Women and Gender in Islam. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 15.

- Ahmed, Leila (1992). Women and Gender in Islam. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 27–28.

- Richard Freund. "The Veiling of Women in Judaism, Christianity and Islam. A Guide to the Exhibition" (PDF). University of Hartford. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 August 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- Ahmed, Leila (1992). Women and Gender in Islam. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 26–28.

- Ahmed, Leila (1992). Women and Gender in Islam. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 35.

- Ahmed, Leila (1992). Women and Gender in Islam. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 55–56.

- Ahmed, Leila (1992). Women and Gender in Islam. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 53–54.

- >Ahmed, Leila (1992). Women and Gender in Islam. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 55.

- Aslan, Reza (2005). No God but God. Random House. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-4000-6213-3.

- "Surat Al-'Ahzab". Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- Aslan, Reza (2005). No God but God. Random House. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-4000-6213-3.

- John L. Esposito, ed. (2014). "Hijab". The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195125580.001.0001. ISBN 9780195125580.

- Ahmed, Leila (1992). Women and Gender in Islam. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 36.

- Esposito, John (1991). Islam: The Straight Path (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 99.

- Bloom (2002), p.47

- Sara Silverstri (2016). "Comparing Burqa Debates in Europe". In Silvio Ferrari; Sabrina Pastorelli (eds.). Religion in Public Spaces: A European Perspective. Routledge. p. 276. ISBN 9781317067542.

- Leila Ahmed (2014). A Quiet Revolution: The Veil's Resurgence, from the Middle East to America. Yale University Press.

- "Retro Middle East: The rise and fall of the miniskirt". albawaba.com. 18 August 2013. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- "Bhutto's Pakistan". Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- "Pakistan's swinging 70s". Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- Robinson, Jeremy Bender, Melia. "25 photos show what Iran looked like before the 1979 revolution turned the nation into an Islamic republic". Business Insider.

- "theguardian.com, 3 September 2015, accessed 23 October 2016". Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- https://en.qantara.de/content/women-in-turkey-the-headscarf-is-slipping?page=0%2C1. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Turkey's fraught history with headscarves". Public Radio International. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Why Turkey Lifted Its Ban on the Islamic Headscarf". National Geographic News. 12 October 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Cover Story". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- El Guindi, Fadwa; Zuhur, Sherifa. "Ḥijāb". The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Archived from the original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- Bullock, Katherine (2000). "Challenging Medial Representations of the Veil". The American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences. 17 (3): 22–53.

- Elsaie, Adel. "Dr". United States of Islam. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012.

- Patrick Johnston (19 August 2016). "Kimia Alizadeh Zenoorin Becomes The First Iranian Woman To Win An Olympic Medal". Reuters/Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- Winter, Bronwyn (2006). "The Great Hijab Coverup". Off Our Backs; A Women's Newsjournal. 36 (3): 38–40. JSTOR 20838653.

- "Naghmeh Kiumarsi Official Website | News". naghmehkiumarsi.org. Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- Istanbul, Hannah Lucinda Smith (29 December 2017). "Iran surprises by relaxing Islamic dress code for women". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- "Fashion police get tough in Tehran". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- Chaker, Zina; Chang, Felicia M.; Hakim-Larson, Julie (1 June 2015). "Body satisfaction, thin-ideal internalization, and perceived pressure to be thin among Canadian women: The role of acculturation and religiosity". Body Image. 14: 85–93. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.04.003. ISSN 1740-1445. PMID 25932974.

- Mussap, Alexander J. (1 March 2009). "Strength of faith and body image in Muslim and non-Muslim women". Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 12 (2): 121–127. doi:10.1080/13674670802358190. ISSN 1367-4676.

- Eid, Paul (2 September 2015). "Balancing agency, gender and race: how do Muslim female teenagers in Quebec negotiate the social meanings embedded in the hijab?". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 38 (11): 1902–1917. doi:10.1080/01419870.2015.1005645. ISSN 0141-9870.

- Dunkel, Trisha M.; Davidson, Denise; Qurashi, Shaji (1 January 2010). "Body satisfaction and pressure to be thin in younger and older Muslim and non-Muslim women: The role of Western and non-Western dress preferences". Body Image. 7 (1): 56–65. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.10.003. ISSN 1740-1445. PMID 19945924.

- Tolaymat, Lana D.; Moradi, Bonnie (2011). "U.S. Muslim women and body image: Links among objectification theory constructs and the hijab". Journal of Counseling Psychology. 58 (3): 383–392. doi:10.1037/a0023461. ISSN 1939-2168. PMID 21604859.

- Swami, V. (2013), Marich, J. (ed.), "The influence of the hijab (Islamic head-cover) on interpersonal judgments of women: a replication and extension", The psychology of women: diverse perspectives from the modern world, Nova Science Publishers, pp. 128–140, ISBN 978-1-62257-899-3, retrieved 15 February 2020

- Droogsma, Rachel Anderson (1 August 2007). "Redefining Hijab: American Muslim Women's Standpoints on Veiling". Journal of Applied Communication Research. 35 (3): 294–319. doi:10.1080/00909880701434299. ISSN 0090-9882.

- Swami, Viren; Miah, Jusnara; Noorani, Nazerine; Taylor, Donna (2014). "Is the hijab protective? An investigation of body image and related constructs among British Muslim women". British Journal of Psychology. 105 (3): 352–363. doi:10.1111/bjop.12045. ISSN 2044-8295. PMID 25040005.

- Kertechian, Sevag K.; Swami, Viren (25 November 2016). "The hijab as a protective factor for body image and disordered eating: a replication in French Muslim women". Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 19 (10): 1056–1068. doi:10.1080/13674676.2017.1312322. ISSN 1367-4676.

- Demmrich, Sarah; Atmaca, Sümeyya; Dinç, Cüneyt (11 December 2017). "Body Image and Religiosity among Veiled and Non-Veiled Turkish Women". Journal of Empirical Theology. 30 (2): 127–147. doi:10.1163/15709256-12341359. ISSN 1570-9256.

- Ramezani, Reza (spring 2007). Hijab dar Iran az Enqelab-e Eslami ta payan Jang-e Tahmili Archived 2 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine [Hijab in Iran from the Islamic Revolution to the end of the Imposed war] (Persian), Faslnamah-e Takhassusi-ye Banuvan-e Shi’ah [Quarterly Journal of Shiite Women] 11, Qom: Muassasah-e Shi’ah Shinasi, pp. 251-300, ISSN 1735-4730

- Elizabeth M. Bucar (2011). Creative Conformity: The Feminist Politics of U.S. Catholic and Iranian Shi'i Women. Georgetown University Press. p. 118. ISBN 9781589017528.

- "قانون مجازات اسلامی (Islamic Penal Code), see ماده 102 (article 102)". Islamic Parliament Research Center. Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- Elizabeth M. Bucar (2011). Creative Conformity: The Feminist Politics of U.S. Catholic and Iranian Shi'i Women. Georgetown University Press. p. 118. ISBN 9781589017528.

exposure of head, hair, arms or legs, use of makeup, sheer or tight clothing, and clothes with foreign words or pictures

- Sanja Kelly; Julia Breslin (2010). Women's Rights in the Middle East and North Africa: Progress Amid Resistance. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 126. ISBN 9781442203976.

- Behnoosh Payvar (2016). Space, Culture, and the Youth in Iran: Observing Norm Creation Processes at the Artists' House. Springer. p. 73. ISBN 9781137525703.

- BBC Monitoring (22 April 2016). "Who are Islamic 'morality police'?". BBC. Archived from the original on 13 April 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- "Iranians worry as morality police go undercover". AP/CBS News. 27 April 2016. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "Iran must protect women's rights advocates". UN OHCHR. 6 May 2019.

- Strategies for promotion of chastity (Persian), the official website of Iranian Majlis (04/05/1384 AP, available online Archived 19 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine)

- Jewel Topsfield (7 April 2016). "Ban on outdoor music concerts in West Aceh due to Sharia law". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- "Saudi's Crown Prince Says Abaya Not Necessary for Women". Expatwoman. 20 March 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- Goldman, Russell (3 May 2016). "What's That You're Wearing? A Guide to public dress". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- Marfuqi, Kitab ul Mar'ah fil Ahkam, pg 133

- Abdullah Atif Samih (7 March 2008). "Do women have to wear niqaab?". Islam Q&A. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- Munajjid (7 March 2008). "Shar'i description of hijab and niqaab". Islam Q&A. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- "Correct view on the ruling on covering the face - islamqa.info".

- Said al Fawaid (7 March 2008). "Articles about niqab". Darul Ifta. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- Moqtasami (1979), pp. 41–44

- "fashion abaya in Saudi Arabia". Reuters. 29 June 2018.

- "Women in Saudi Arabia do not need to wear head cover, says crown prince".

- CLOTHING ii. In the Median and Achaemenid periods at Encyclopædia Iranica

- El-Guindi, Fadwa, Veil: Modesty, Privacy, and Resistance, Berg, 1999

- "Turkey's AKP discusses hijab ruling". Al Jazeera. 6 June 2008. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- "Quiet end to Turkey's college headscarf ban". BBC News. 31 December 2010. Archived from the original on 28 June 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- "Tunisia's Hijab Ban Unconstitutional". 11 October 2007. Archived from the original on 20 July 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- "Country passes law 'to stop Muslim women wearing hijabs'". September 2017. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- "Majority-Muslim Tajikistan passes law to discourage wearing of hijabs". Archived from the original on 29 August 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- Mardell, Mark. "Dutch MPs to decide on burqa ban" Archived 12 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, 16 January 2006. Accessed 6 June 2008.

- Köksal Baltaci (27 September 2017). "Austria becomes latest European country to ban burqas — but adds clown face paint, too". USA Today. Archived from the original on 24 February 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2017.