Limerick Athenaeum

The Limerick Athenaeum was a centre of learning, established in Limerick city, Ireland, in 1852.

Theatre Royal, Royal Cinema | |

Limerick Athenaeum circa 1880 | |

| Address | 2 Cecil Street Limerick Ireland |

|---|---|

| Owner | Limerick City VEC |

| Capacity | 600 |

| Current use | Idle |

| Construction | |

| Opened | 1855 |

| Closed | 1998 |

| Rebuilt | 1947, 1989, 1991 |

| Years active | 1855-1998 |

| Architect | John Fogerty |

Background

"Athenaeum", also Athenæum or Atheneum, is used in the names of institutions or periodicals for literary, scientific, or artistic study. It may also be used in the names of educational institutions. The name is formed from the name of the classical Greek goddess Athena, the goddess of arts and wisdom.

John Wilson Croker founded the Athenaeum Club in London in 1823, beginning an international movement for the promotion of literary and scientific learning. Croker was of Anglo-Irish parentage with connections in County Limerick. Other founder members of this club included William Blake, Robert Peel, Lord John Russell, Sir Thomas Lawrence, T.R. Malthus, Sir Walter Scott, Michael Faraday, William M. Turner, and others. The club published a literary and scientific journal, The Athenaeum, which survived until 1921.

The Athenaeum movement spread throughout the world. In England, Athenaii were located at Bristol, Leeds, London, and Manchester. In Ireland, the Cork Athenaeum was built by public subscription in 1853 (this was later to become the Cork Opera House), and Dublin had an Athenaeum at 43 Grafton Street in 1856. In Scotland, the Glasgow Athenaeum started in Ingram Street in 1847 and is today's Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. In the United States of America, Athenaii are in Boston, Chicago, New York City, and other cities.

Founder

The founder of the Limerick Athenaeum was William Lane Joynt, who achieved the unique distinction of being elected Mayor of Limerick in 1862 and Lord Mayor of Dublin in 1867. In 1869, he was appointed the Crown and Treasury Solicitor for Ireland. Lane Joynt apprenticed as a solicitor to Matthew Barrington of the leading law firm Barrington and Co. The Barrington family lived at Glenstal Castle and built Barrington's Hospital for the citizens of Limerick. In 1853, Lane Joynt, as president of the Limerick Literary and Scientific Society, proposed the establishment of a Limerick Athenaeum in a letter written to the society's committee. The letter was entitled "Suggestions For The Establishment Of A Limerick Athenaeum", and its embodying suggestions were adopted unanimously.[1][2] He died in 1895, and is buried in the grounds of the churchyard at St. John's Square, Limerick.[3]

Early years

Following a public meeting in April 1853, a fund-raising committee was established, and they had amassed £1200 by October of that year. One of the first subscribers was Sir Richard Bourke, governor of the colony of New South Wales in Australia, who founded the present Australian education system and in 1855 the first farmers' association in Ireland, the Farmers' Club.[4] A building at No. 2 Upper Cecil Street was purchased from Limerick Corporation in February 1855, and work began on its conversion. The building had been constructed in 1833-34 as the offices of St. Michael's Parish Commissioners to the plans of John Fogarty, who is noted for the design of Plassey House, now the nerve centre of the University of Limerick.

It reopened on 3 December 1855 with classes provided by the School of Ornamental Art. The new Athenaeum Hall, which was constructed adjacent to the original building, was opened to the public on 3 January 1856, with the first Annual General Meeting of the Athenaeum Society. It was described as the 'finest hall for its special purposes, in Ireland'.[5] Natural light came from three domes in the high roof, and it had an orchestra gallery and seating for up to 600 people. The building was both lecture hall and theatre, intended for both entertainment and education.

The first show to be staged, in January 1856, was a panorama show of the Crimean War. These shows used early multimedia techniques of sound, provided by an orchestra, visual effects via the magic lantern, and a live narration by an actor to expose the reality of current events. At the time, it was a milestone in communication techniques and a precursor to the factual documentaries of television. Many of the leading international theatrical performers of the day graced the theatre of the Athenaeum over the coming years. Some notable performers included:

- Catherine Hayes, the Limerick-born, internationally acclaimed diva, gave a benefit performance of Handel's Messiah in aid of the procurement of musical instruments for the Limerick Harmonic Society - 1857

- General Tom Thumb and P. T. Barnum - 1858

- Percy French, a leading songwriter and entertainer of his day - 1894, 1899, 1912

- John McCormack, the famous opera singer - 1905

The Athenaeum also hosted a regular series of lectures and debates. Some of the more notable speakers included:

- William Smith O'Brien, an Irish nationalist, Member of Parliament (MP) and leader of the Young Ireland movement - 1857

- John Bright, MP, English orator and statesman - 1868

- Isaac Butt, founder of the Home Rule League - 1872, 1877

- William Abraham, MP and Irish Land League activist - 1875, 1889

- Charles Stewart Parnell, Irish nationalist, political leader, land reform agitator, Home Rule MP - 1880

- John Redmond, MP and leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party - 1882, 1889

- Michael Davitt, Irish Republican and founder of the Irish National Land League - 1884

- Oscar Wilde[6] - 1884

- Maud Gonne, the Irish revolutionary, feminist, and actress - 1900

- Michael Cusack, co-founder of the GAA - 1903

- Christabel Pankhurst, suffragette and daughter of Emmeline Pankhurst - 1911

- Sir Roger Casement and Patrick Pearse, Irish Republicans and architects of the 1916 Easter Rising - 1915

Sports clubs

The Athenaeum provided meeting rooms where people got together to form a variety of sporting clubs. The Athenaeum Archives have the Reports of AGMs of many of these clubs, which taken with the accounts of the fund-raising social events and concerts, provide insight into sporting life in the city in the 19th century. Some of the notable clubs that can trace their foundations back to the Athenaeum are:

- Limerick Boat Club - founded in 1870

- Garryowen Football Club - founded in 1884[7]

- Limerick Golf Club - founded in 1891[8]

Athenaeum Permanent Picturedrome

The Athenaeum Hall began to double as a theatre and cinema in the early 1900s, a common trend in theatres with the advancement of silent films, newsreels and 'talkies' into the 1930s. Control of the Athenaeum had been passed to Limerick Corporation and the Technical Education Committee (later the Vocational Education Committee) in 1896. In 1912, the Technical Education classes and part of the Limerick School of Art moved from the Athenaeum building to newly constructed premises in O'Connell Avenue. The now-vacant lecture hall was leased out by the Technical Education Committee of the Corporation and reopened as the Athenaeum Permanent Picturedrome. It operated successfully until the effects of the Second World War began to take hold in the early 1940s. The first newsreel shown at the Athenaeum was in 1913 with a film of the Garryowen v University College Cork rugby match, which created intense excitement in the city. Notably, the Athenaeum opened its 'talkie' programme with the Al Jolson musical film Say It with Songs to celebrate St Patrick's Day in 1930.

In October 1930, the Athenaeum installed the ultramodern Western Electric Sound System, in time for the newly released Juno and the Paycock, an Alfred Hitchcock adaption of Seán O'Casey's play. However, the film only received one showing before members of the Limerick Confraternity raided the projection box and stole two reels of the film which were later burnt outside the cinema by a mob of at least 20 men in Cecil Street.[9] Outbreaks of moral condemnation from Limerick's pulpits had "filthy" cinema posters removed by lay vigilantes, including 1932's Blonde Venus, starring Marlene Dietrich, and Cecil B. DeMille's 1934 version of Cleopatra. The Sunday Times previewed Sotheby's spring 1996 auction of old cinema posters in which their investment analyst stated, "(they) have become an art genre in their own right" and placed an estimate of £6,000 and £10,000 on the posters, respectively.[10]

The effects of the Second World War became too much for the tenants, and they gave up their lease in 1941. Attempts by other interested parties, including theatre groups, to negotiate a lease with the VEC proved unsuccessful, with only sporadic openings over the next few years. The last films in the Athenaeum Cinema were shown in November 1946.[3]

The Royal Cinema

The completely reconstructed Royal Cinema, with 600 seats, opened with a fanfare of publicity on 17 November 1947. The first film to be shown was Cole Porter's musical Night and Day.[11] Limerick cinema goers enjoyed many films at the Royal over the next 30 years or so. In the early 1980s, a number of factors began to impact the cinema trade. The growing popularity and availability of videocassette recorders inspired the growing trade of the video rental shops, which in turn accelerated a decline in cinema audiences. A further problem in Ireland was the 23% VAT rate on cinema admissions. Indeed, this was cited as an "intolerable burden" and the reason for the ultimate closure of the cinema.[12] A Limerick Leader article noted that Limerick, which once had 4,600 cinema seats, was now reduced to one cinema, the Carlton.[12] Efforts by Alderman Jim Kemmy, TD, and others to save the cinema, failed. The last film to be screened at the cinema was Police Academy 2, in March 1985.

The Theatre Royal

The dereliction of the old Athenaeum continued until 1989, when it was purchased by a local businessman. In an interview with the Limerick Post, a director of the new Theatre Royal Company said, "We see it primarily as a theatre and would compare it to the Olympia or the Gaiety in Dublin..."[13] During the renovation, many of the architectural features of the original hall were carefully restored, including the three ceiling domes.[14]

According to the new management, the purpose of the new theatre was to provide live music concerts to young people and to provide them with an alternative venue.[14] After a slow start, the venue began to gain in popularity, and for Mary Black's concert in December 1989, Limerick audiences queued in the streets outside the theatre for the first time since John McCormack's concert in 1905.[3] In February 1990, classical music was reintroduced to the theatre when the Tuckwell Wind Quartet gave a performance, and two weeks later, the Irish Operatic Repertory Company from Cork revived opera at the Royal with a choir of 45 singers.[3]

Disaster struck the Theatre Royal on 6 March 1990, when the newly restored theatre went on fire. The cause was an electrical fault. No personal injuries were sustained, but the damage to the theatre was severe.[3] The theatre required major reconstruction once again and was reopened on Sunday, 3 February 1991, by Mr Brendan Daly, T.D., Minister of State for Heritage Affairs, Department of the Taoiseach, in the presence of the mayor, Mr. Madden, and members of Limerick Corporation, to a musical performance by Mary Black.

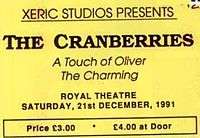

In December 1991, a relatively unknown local band called The Cranberries played to a small audience in the theatre. Word spread quickly, and their second performance a few weeks later was a sell-out.[3] The band went on to sell an estimated 43 million albums worldwide[15] before disbanding in 2003. The band returned to play in the theatre a number of times up to 1994.

Channel 4 filmed a sequence of their award-winning comedy series, Father Ted, in the theatre in December 1995. Indeed, both Dermot Morgan and Ardal O'Hanlon were regular performers at the theatre during the 1990s.[3] The Corrs (1994), Boyzone (1994, 1995) and The Prodigy (1995) all performed at the Theatre Royal before they achieved mainstream popularity. Other notable performers included Dolores Keane, Sharon Shannon, Don Baker, Paul Brady, Davy Spillane, Liam Ó Maonlaí, Julian Lloyd Webber, and The Saw Doctors. Despite the relative success of the venue, the Theatre Royal closed for the last time in 1998.[16]

In Darren Shan's 2000 novel Cirque du Freak, the eponymous freak show takes place in an old abandoned theatre based on the writer's recollections of the Theatre Royal.[17]

Current use

The original Athenaeum Building was used as a school from the 1940s to the 1960s and was known in Limerick as the "One Day" Boys School.[18] In 1973, the City VEC moved its administrative headquarters from O'Connell Street to the Athenaeum Building. In 2003, a €1m Department of Education and Science-funded refurbishment programme was completed. This refurbishment project was carefully designed to preserve the historical building's important architectural features, including external facade, internal stairways, and sash windows, while at the same time providing the most modern in terms of access, furnishing, and technology.[18]

In the late 1990s, ownership of the Athenaeum Hall reverted to the VEC.[18] In 2012, the VEC applied for planning permission for a film and digital media centre in the hall. The project involves the provision of three auditoriums, multipurpose lecture and performance space, digital lounge, editing studios, meeting rooms, and a cáfe. The objectives of the centre are to provide a centre of excellence in film and digital media and create opportunities for the hundreds of media and computer science students who graduate from Limerick colleges every year.[19] Limerick City Council granted planning permission in late 2012 and the first phase of the development it is expected to be ready for fit-out by mid-2014. Further development of the site is to include incubation space for business start-ups and a permanent home for the Limerick Museum of Film. The museum will house a private collection which is the second-largest in the country after that of the Irish Film Institute.[19]

References

- Lane Joynt, William, Suggestions For The Establishment Of A Limerick Athenaeum, 1853. George McKern & Sons, Limerick.

- Lane Joynt, William, Suggestions For The Establishment Of A Limerick Athenaeum, Limerick Chronicle, 9, 13, 16, 20 April 1853.

- MacMahon, James A. (1996) If Walls Could Talk - The Limerick Athenaeum: The Story Of An Irish Theatre Since 1852 Archived 17 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Limerick Chronicle, 10 June 1997.

- Limerick Chronicle, 5 December 1855.

- Ryan, L., UL to host commemoration of Wilde's visit to Limerick, Limerick Leader, 12 June 2013.

- Garryowen FC Website - History Archived 9 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Cotter, Patrick J., A History of Limerick Golf Club, 1891-1991, 1991, p.42

- Limerick Chronicle, 11 November 1930.

- The Sunday Times, 10 December 1995.

- Limerick Leader, 15 November 1947.

- Limerick Leader, 9 March 1985.

- Limerick Post, 29 July 1989.

- Limerick Post, 28 October 1989.

- FAQ - The Cranberries Russian Fan-Site Archived 30 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Lost Theatres, Concert and Music Halls In Ireland. Archived 28 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Interview with Darren Shan". 7 March 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- Limerick VEC Website - Building History

- €10 million Royal plan to kickstart city regeneration, The Limerick Post, 5 January 2013.

Further reading

- From Small Beginnings - The Story of the Limerick School of Art and Design, 1852–2002, J.J. Hogan, Limerick Institute of Technology, 2002

- If Walls Could Talk - The Limerick Athenaeum: The Story Of An Irish Theatre Since 1852, James A. MacMahon, 1996