Videocassette recorder

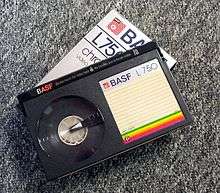

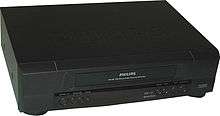

A videocassette recorder (VCR) or video recorder is an electromechanical device that records analog audio and analog video from broadcast television or other source on a removable, magnetic tape videocassette, and can play back the recording. Use of a VCR to record a television program to play back at a more convenient time is commonly referred to as timeshifting. VCRs can also play back prerecorded tapes. In the 1980s and 1990s, prerecorded videotapes were widely available for purchase and rental, and blank tapes were sold to make recordings.

Most domestic VCRs are equipped with a television broadcast receiver (tuner) for TV reception, and a programmable clock (timer) for unattended recording of a television channel from a start time to an end time specified by the user. These features began as simple mechanical counter-based single-event timers, but were later replaced by more flexible multiple-event digital clock timers. In later models the multiple timer events could be programmed through a menu interface displayed on the playback TV screen ("on-screen display" or OSD). This feature allowed several programs to be recorded at different times without further user intervention, and became a major selling point.

History

Early machines and formats

The history of the videocassette recorder follows the history of videotape recording in general. In 1953, Dr. Norikazu Sawazaki developed a prototype helical scan video tape recorder.[1]

Ampex introduced the quadruplex videotape professional broadcast standard format with its Ampex VRX-1000 in 1956. It became the world's first commercially successful videotape recorder using two-inch (5.1 cm) wide tape.[2] Due to its high price of US$50,000, the Ampex VRX-1000 could be afforded only by the television networks and the largest individual stations.[3][4][5]

In 1959, Toshiba introduced a "new" method of recording known as helical scan, releasing the first commercial helical scan video tape recorder that year.[6] It was first implemented in reel-to-reel videotape recorders (VTRs), and later used with cassette tapes.

In 1963 Philips introduced their EL3400 1-inch helical scan recorder, aimed at the business and domestic user, and Sony marketed the 2" PV-100, their first reel-to-reel VTR, intended for business, medical, airline, and educational use.[7]

First home video recorders

The Telcan (Television in a Can), produced by the UK Nottingham Electronic Valve Company in 1963, was the first home video recorder. It was developed by Michael Turner and Norman Rutherford. It could be purchased as a unit or in kit form for £60, equivalent to approximately £1,100 (over US$1,600) in 2014 currency. However, there were several drawbacks as it was expensive, not easy to assemble, and could record only 20 minutes at a time. It recorded in black-and-white, the only format available in the UK at the time.[8][9][10] An original Telcan Domestic Video Recorder can be seen at the Nottingham Industrial Museum.

The half-inch tape Sony model CV-2000, first marketed in 1965, was their first VTR intended for home use.[11] It was the first fully transistorized VCR.[12] Ampex and RCA followed in 1965 with their own reel-to-reel monochrome VTRs priced under US$1,000 for the home consumer market.

The EIAJ format was a standard half-inch format used by various manufacturers. EIAJ-1 was an open-reel format. EIAJ-2 used a cartridge that contained a supply reel; the take-up reel was part of the recorder, and the tape had to be fully rewound before removing the cartridge, a slow procedure.

The development of the videocassette followed the replacement by cassette of other open reel systems in consumer items: the Stereo-Pak four-track audio cartridge in 1962, the compact audio cassette and Instamatic film cartridge in 1963, the 8-track cartridge in 1965, and the Super 8 home movie cartridge in 1966.

In 1972, videocassettes of movies became available for home use.[13]

Sony U-matic

Sony demonstrated a videocassette prototype in October 1969, then set it aside to work out an industry standard by March 1970 with seven fellow manufacturers. The result, the Sony U-matic system, introduced in Tokyo in September 1971, was the world's first commercial videocassette format. Its cartridges, resembling larger versions of the later VHS cassettes, used 3/4-inch (1.9 cm) tape and had a maximum playing time of 60 minutes, later extended to 80 minutes. Sony also introduced two machines (the VP-1100 videocassette player and the VO-1700, also called the VO-1600 video-cassette recorder) to use the new tapes. U-matic, with its ease of use, quickly made other consumer videotape systems obsolete in Japan and North America, where U-matic VCRs were widely used by television newsrooms (Sony BVU-150 and Trinitron DXC 1810 video camera) schools and businesses. But the high cost - US$1,395 in 1971 for a combination TV/VCR, equivalent to $8,850 in 2020 dollars – kept it out of most homes.[14]

Philips "VCR" format

In 1970, Philips developed a home video cassette format specially made for a TV station in 1970 and available on the consumer market in 1972. Philips named this format "Video Cassette Recording" (although it is also referred to as "N1500", after the first recorder's model number).[15]

The format was also supported by Grundig and Loewe. It used square cassettes and half-inch (1.3 cm) tape, mounted on coaxial reels, giving a recording time of one hour. The first model, available in the United Kingdom in 1972, was equipped with a simple timer that used rotary dials. At nearly £600, it was expensive and the format was relatively unsuccessful in the home market. This was followed by a digital timer version in 1975, the N1502. In 1977 a new, incompatible, long-play version ("VCR-LP") or N1700, which could use the same blank tapes, sold quite well to schools and colleges.

Avco Cartrivision

The Avco Cartrivision system, a combination television set and VCR from Cartridge Television Inc. that sold for US$1,350, was the first videocassette recorder to have pre-recorded tapes of popular movies available for rent. Like the Philips VCR format, the square Cartrivision cassette had the two reels of half-inch tape mounted on top of each other, but it could record up to 114 minutes, using an early form of video format that recorded every other video field and played it back three times.

Cassettes of major movies such as The Bridge on the River Kwai and Guess Who's Coming to Dinner were ordered via catalog at a retailer, delivered by parcel mail, and then returned to the retailer after viewing. Other cassettes on sports, travel, art, and how-to topics were available for purchase. An optional monochrome camera could be bought to make home videos. Cartrivision was first sold in June 1972, mainly through Sears, Macy's, and Montgomery Ward department stores in the United States. The system was abandoned thirteen months later after poor sales.

Mass-market success

VCR started gaining mass market traction in 1975. Six major firms were involved in the development of the VCR: RCA, JVC, AMPEX, Matsushita Electric / Panasonic, Sony, and Toshiba. Of these, the big winners in the growth of this industry were Japanese companies Matsushita Electric / Panasonic, JVC, and Sony, which developed more technically advanced machines with more accurate electronic timers and greater tape duration. The VCR started to become a mass market consumer product; by 1979 there were three competing technical standards using mutually incompatible tape cassettes.

The industry boomed in the 1980s as more and more customers bought VCRs. By 1982, 10% of households in the United Kingdom owned a VCR. The figure reached 30% in 1985 and by the end of the decade well over half of British homes owned a VCR.[16]

Earlier machines used mechanically-operated control switches; these were replaced by microswitches, solenoids and motor-driven mechanisms.

VHS vs. Betamax

The two major standards were Sony's Betamax (also known as Betacord or just Beta), and JVC's VHS (Video Home System), which competed for sales in what became known as the format war.[17]

Betamax was first to market in November 1975, and was argued by many to be technically more sophisticated in recording quality,[18] although many users did not perceive a visual difference. The first machines required an external timer, and could only record one hour, or two hours at lower quality (LP). The timer was later incorporated within the machine as a standard feature.

The rival VHS format, introduced in Japan by JVC in September 1976, introduced in the United States in July 1977 by RCA, had a longer two-hour recording time with a T-120 tape, or four hours in lower-quality "long play" mode (RCA SelectaVision models, introduced in September 1977).

In 1978 the majority of consumers in the U.K. chose to rent rather than purchase this new expensive home entertainment technology. JVC introduced the HR3300 model[19] with E-30, E-60, (E-120 VHS-1 1976), E-180 minute cassette tapes with up to three hours=(VHS-2 1977)) recording time, a thinner 4 hour length (E240 tape VHS-3 1981) soon followed (E-400 VHS-5 last edition 1999).

The rental market was a contributing factor for acceptance of the VHS, for a variety of reasons. In those pre-digital days TV broadcasters could not offer the wide choice of a rental store, and tapes could be played as often as desired. Material was available on tape with violent or sexual scenes not available on broadcasts. Home video cameras allowed tapes to be recorded and played back.

Two hours and 4 hours recording times were considered enough for recording movies and sports. Although Sony later introduced L-500 (2 hour) and L-750 (3 hour) Betamax tapes in addition to the L-250 (1 hour) tape, the consumer market had swiftly moved toward the VHS system as a preferred choice. During the 1980s dual-speed (long play) models of both Beta and VHS recorders were introduced, allowing much longer recording times. The recording length on World Wide Standard on consumer video recorders (VHS) Was 8hrs with PAL colour encoding and 5hs-46mins with NTSC color encoding. The total recording length on The World Wide Standard On Professional Broadcasting (Betamax) was 3hrs 35mins on PAL colour configuration, and 5hrs on NTSC color configuration.

Longer tapes became available a few years later, extending to 10hrs and then 12hrs LP on PAL (Europe) and 7hrs 50mins and then further extended with VHS-5 (Final edition of the Video Home System) in 1999 TO 8hrs 16mins on NTSC (North America, Japan). Betamax tape length was extended only using a DigiBetacam-40 or HDCAM cassette to 4hrs 20mins on PAL and 6hrs 30mins on NTSC models.

With the introduction of DVD recorders, combined VHS and DVD recorders were produced, allowing both types of media to be played, and transfer of tape material to DVD.

Philips Video 2000

A third format, Video 2000, or V2000 (also marketed as "Video Compact Cassette") was developed and introduced by Philips in 1978, sold only in Europe. Grundig developed and marketed their own models based on the V2000 format. Most V2000 models featured piezoelectric head positioning to dynamically adjust tape tracking. V2000 cassettes had two sides, and like the audio cassette could be flipped over halfway through their recording time, which gave them up to twice the recording length of VHS tapes. User switchable record-protect levers were used instead of the breakable lugs on VHS and Beta cassettes.

The half-inch tape used contained two parallel quarter-inch tracks, one for each side. It had a recording time of 4 hours per side, later extended to 8 hours per side on a few models. Machines had a 'real time' tape position counter with the information retained on the tape, so when tapes were loaded the position was known; this feature was only implemented on VHS recorders much later. V2000 became available in early 1979, later than its two rivals. The V2000 system did not sell well, and was discontinued in 1985.

Other early formats

Some less successful consumer videocassette formats include:

- V-Cord, launched by Sanyo in 1974

- VX, launched by Panasonic in 1975

- Compact Video Cassette (CVC), developed by Funai and Technicolor and introduced in 1980.

Legal challenges

In the early 1980s US film companies fought to suppress the VCR in the consumer market, citing concerns about copyright violations. In Congressional hearings, Motion Picture Association of America head Jack Valenti decried the "savagery and the ravages of this machine" and likened its effect on the film industry and the American public to the Boston strangler:

I say to you that the VCR is to the American film producer and the American public as the Boston strangler is to the woman home alone.

— Hearings before the Subcommittee on Courts, Civil Liberties and the Administration of Justice of the Committee of the Judiciary, House of Representatives, Ninety-seventh Congress, Second Session on H.R. 4783, H.R. 4794 H.R. 4808, H.R. 5250, H.R. 5488, and H.R. 5705, Serial No 97, Part I, Home Recording of Copyrighted Works, April 12, 1982. US Government Printing Office.[20]

In the case Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc., the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the device was allowable for private use. Subsequently the film companies found that making and selling video recordings of their productions had become a major income source.

Shortcomings

The video cassette recorder is sensitive to changes in temperature and humidity. If the machine (or tape) was moved from a cold to a hotter environment there could be condensation of moisture on the internal parts, such as the rotating video head drum. Some later models were equipped with a moisture detector which would prevent operation in this case, but it could not detect moisture on the surface of a tape.

Magnetic tapes could be mechanically damaged when ejected from the machine due to moisture or other problems. Rubber drive belts and rollers hardened with age, causing malfunctions.[21] Faults such as these damaged the tape irreversibly, a particular problem with irreplaceable tapes filmed by users. VHS tapes recorded in LP or EP/SLP mode were more sensitive to minor head misalignment over time or from machine to machine. Tapes recorded on a machine made before 1995 tend to not play well on newer machines due to slight changes in helical scanning head design.

Decline

The videocassette recorder remained in home use throughout the 1980s and 1990s, despite the advent of competing technologies such as LaserDisc (LD) and Video CD (VCD). While Laserdisc offered higher quality video and audio, the discs are heavy (weighing about one pound each), cumbersome, much more prone to damage if dropped or mishandled, and furthermore only home LD players, not recorders, were available. The VCD format found a niche with Asian film imports, but did not sell widely. Many Hollywood studios did not release feature films on VCD in North America because the VCD format had no means of preventing perfect copies being made on CD-R discs, which were already popular when the format was introduced. In an attempt to lower costs, manufacturers began dropping nonessential features from their VCR models. The built-in display was dropped in favor of on screen display for setup, programming, and status, and many buttons were eliminated from the VCR's front panel, their functions accessible only from the VCR's remote control.

From about 2000 DVD became the first universally successful optical medium for playback of pre-recorded video, as it gradually overtook VHS to become the most popular consumer format. DVD recorders and other digital video recorders dropped rapidly in price, making the VCR obsolete. DVD rentals in the United States first exceeded those of VHS in June 2003.

The declining market combined with a US Federal Communications Commission mandate effective 1 March 2007, that all new TV tuners in the US be ATSC tuners encouraged major electronics makers, except Funai, JVC, and Panasonic, to end production of standalone units for the US market. Most new standalone VCRs in the US since then can only record from external baseband sources (usually composite video), including CECBs which (by NTIA mandate) all have composite outputs, as well as those ATSC tuners (including TVs) and cable boxes that come with composite outputs. However, JVC did ship one model of D-VHS deck with a built-in ATSC tuner, the HM-DT100U, but it remains extremely rare, and therefore expensive. In July 2016, Funai Electric, the last remaining manufacturer of VHS recorders, announced it would cease production of VHS recorders by the end of the month.[22][23]

As a result of winning the format war over HD DVD, the new high definition optical disc format Blu-ray Disc was expected to replace the DVD format. However, with many homes still having a large supply of VHS tapes and with all Blu-ray players designed to play regular DVDs and CDs by default, some manufacturers began to make VCR/Blu-ray combo players.[24]

Remaining niche in recording

Although consumers have passed over videocassettes for home video playback in favor of DVDs since the early 2000s, VCRs still retained a significant share in home video recording during that decade. While the adoption of DVD players has been strong, DVD recorders for home theater use have been slow to pick up (although DVD recorder-writer drives became de facto standard equipment in personal computers in the mid-2000s).

Although technologically superior to VHS, there were several main drawbacks with recordable DVDs that slowed their adoption. When standalone DVD recorders first appeared on the Japanese consumer market in 1999, these early units were expensive, costing between US$2500–$4000. Different DVD recordable formats also caused confusion, as early units supported only DVD-RAM and DVD-R discs, but the more recent units can record to all major formats DVD-R, DVD-RW, DVD+R, DVD+RW, DVD-R DL and DVD+R DL. Some of these DVD formats are not rewritable, whereas videocassettes could be recorded over repeatedly (notwithstanding physical wear). Another important drawback of DVD recording is that one single-layer DVD is limited to around 120 minutes of recording if the quality is not to be significantly reduced, while VHS tapes are readily available up to 210 minutes (standard play) in NTSC areas and even 300 minutes in PAL areas. Dual layer DVDs, which increase the high quality recording mode to almost four hours, are increasingly available, but the cost of this medium was still relatively high compared to standard single-layer discs. Another factor was the increasing use of digital video file formats and online video sharing, skipping physical media entirely. For these reasons, DVD recorders never took hold of the video recording market like VCRs had.

Digital video recorders have since come to dominate the market for home recording of television shows.

Special features

Multi standard

One of the problems faced with the use of video recorders was the exchange of recordings between PAL, SECAM and NTSC countries. Multi Standard video recorders and TV sets gradually overcame these incompatibility problems.

High quality audio (Nicam, AFM, and HiFi)

The U-matic machines were always made with Stereo, and both Betamax and VHS recorded the audio tracks using a fixed linear recording head. However the relatively slow tape speed of Beta and VHS was inadequate for good quality audio, and significantly limited the sound quality. Betamax's release of Beta Hi-Fi in the early 1980s was quickly followed by JVCs release of HiFi audio on VHS (model HR-D725U). Both systems delivered flat full-range frequency response (20 Hz to 20 kHz), excellent 70 dB signal-to-noise ratio (in consumer space, second only to the compact disc), dynamic range of 90 dB, and professional audio-grade channel separation (more than 70 dB). In VHS the incoming HiFi audio is frequency modulated ("Audio FM" or "AFM"), modulating the two stereo channels (L, R) on two different frequency-modulated carriers and recorded using the same high-bandwidth helical scanning technique used for the video signal.

To avoid crosstalk and interference from the primary video carrier, VHS used depth multiplexing, in which the modulated audio carrier pair was placed in the hitherto-unused frequency range between the luminance and the color carrier (below 1.6 MHz), and recorded first. Subsequently, the video head erases and re-records the video signal (combined luminance and color signal) over the same tape surface, but the video signal's higher center frequency results in a shallower magnetization of the tape, allowing both the video and residual AFM audio signal to coexist on tape. (PAL versions of Beta Hi-Fi use the same technique). During playback, VHS Hi-Fi recovers the depth-recorded AFM signal by subtracting the audio head's signal (which contains the AFM signal contaminated by a weak image of the video signal) from the video head's signal (which contains only the video signal), then demodulates the left and right audio channels from their respective frequency carriers. The end result of the complex process is audio of outstanding fidelity, which was uniformly solid across all tape-speeds (EP, LP or SP.)

Such devices were often described as "HiFi audio", "Audio FM" / "AFM" (FM standing for "Frequency Modulation"), and sometimes informally as "Nicam" VCRs (due to their use in recording the Nicam broadcast audio signal). They remained compatible with non-HiFi VCR players since the standard audio track was also recorded, and were at times used as an alternative to audio cassette tapes due to their exceptional bandwidth, frequency range, and extremely flat frequency response.

The 8 mm format always used the video portion of the tape for sound, with an FM carrier between the band space of the chrominance and luminance on the tape. 8 mm could be upgraded to Stereo, by adding an extra FM signal for Stereo difference.

The professional Betacam SP format of videocassette also used AFM on the higher-end "BVW"-series of Betacam SP deck models from Sony (such as the BVW-75) to offer 2 extra tracks of audio alongside the 2 standard Dolby C-encoded linear audio tracks for the format, for a total of 4 audio tracks. However, the 2 AFM tracks were accessible only on those decks equipped with AFM audio (like the BVW-75).

Quality

Due to the path followed by the video and Hi-Fi audio heads being striped and discontinuous—unlike that of the linear audio track—head-switching is required to provide a continuous audio signal. While the video signal can easily hide the head-switching point in the invisible vertical retrace section of the signal, so that the exact switching point is not very important, the same is obviously not possible with a continuous audio signal that has no inaudible sections. Hi-Fi audio is thus dependent on a much more exact alignment of the head switching point than is required for non-HiFi VHS machines. Misalignments may lead to imperfect joining of the signal, resulting in low-pitched buzzing.[25] The problem is known as "head chatter", and tends to increase as the audio heads wear down.

The sound quality of Hi-Fi VHS stereo is comparable to the quality of CD audio, particularly when recordings were made on high-end or professional VHS machines that have a manual audio recording level control. This high quality compared to other consumer audio recording formats such as compact cassette attracted the attention of amateur and hobbyist recording artists. Home recording enthusiasts occasionally recorded high quality stereo mixdowns and master recordings from multitrack audio tape onto consumer-level Hi-Fi VCRs. However, because the VHS Hi-Fi recording process is intertwined with the VCR's video-recording function, advanced editing functions such as audio-only or video-only dubbing are impossible. A short-lived alternative to the hifi feature for recording mixdowns of hobbyist audio-only projects was a PCM adaptor so that high-bandwidth digital video could use a grid of black-and-white dots on an analog video carrier to give pro-grade digital sounds though DAT tapes made this obsolete.

Copy protection

Introduced in 1983, Macrovision is a system that reduces the quality of recordings made from commercial video tapes, DVDs and pay-per-view broadcasts by adding random peaks of luminance to the video signal during vertical blanking. These confuse the automatic level adjustment of the recording VCR which causes the brightness of the picture to constantly change, rendering the recording unwatchable.

When creating a copy-protected videocassette, the Macrovision-distorted signal is stored on the tape itself by special recording equipment. By contrast, on DVDs there is just a marker asking the player to produce such a distortion during playback. All standard DVD players include this protection and obey the marker, though unofficially many models can be modified or adjusted to disable it.

Also, the Macrovision protection system may fail to work on older VCR's made before 1986 and some high end decks built afterwards, usually due to the lack of an AGC system. Newer VHS and S-VHS machines (and DVD recorders) are susceptible to this signal; generally, machines of other tape formats are unaffected, such as all 3 Betamax variants. VCRs designated for "professional" usage typically have an adjustable AGC system, a specific "Macrovision removing" circuit, or Time Base Corrector (TBC) and can thus copy protected tapes with or without preserving the protection. Such VCRs are usually overpriced and sold exclusively to certified professionals (linear editing using the 9-Pin Protocol, TV stations etc.) via controlled distribution channels in order to prevent their being used by the general public (however, said professional VCRs can be purchased reasonably by consumers on the second-hand/used market, depending on the VCR's condition). Nowadays, most DVDs still have copyright protection, but certain DVDs do not have it, usually pornography and bootlegs. However, some DVDs, such as certain DVD sets, do not have the protection against VHS copying, possibly due to the VHS format no longer used as a major retail medium for home video.

Flying erase heads

The flying erase head is a feature that may be found in some high end home VCRs as well as some broadcast grade VCRs to cleanly edit the video.

Normally, the tape is passed longitudinally through two fixed erase heads, one located just before the tape moves to the video head drum and the other right next to the audio/control head stack. Upon recording, the erase heads erase any old recording contained on the tape to prevent anything already recorded on it from interfering with what is being recorded.

However, when trying to edit footage deck to deck, portions of the old recording's video may be between the erase head and video recording heads. This results in a faint rainbow-like noise at and briefly after the point of the cut as the old video recording missed by the fixed erase head is never completely erased as the new recording is printed.

The flying erase head is so-called because an erase head is mounted on the video head drum and rotates around in the same manner as the video heads. In the record mode, the erase head is active and erases the video precisely down to the recorded video fields. The flying erase head runs over the tape and the video heads record the signal virtually instantly after the flying erase head has passed.

Since the erase head erases the old signal right before the video heads write onto the tape, there is no remnant of the old signal to cause visible distortion at and after the moment a cut is made, resulting in a clean edit. In addition, the ability of flying erase heads to erase old video off the tape right before recording new video on it allows the ability to perform insert editing, where new footage can be placed within an existing recording with clean cuts at the beginning and end of the edit.

Variants

In addition to the standard home VCR, a number of variants have been produced over the years. These include combined "all-in-one" devices such as the TV/VCR combo (a TV and VCR in one unit) and DVD/VCR units and even TV/VCR/DVD all-in-one units.

Dual-deck VCRs (marketed as "double-decker") have also been sold, albeit with less success.

Most camcorders produced in the 20th century also feature an integrated VCR. Generally, they include neither a timer nor a TV tuner. Most of these use smaller format videocassettes, such as 8 mm, VHS-C, or MiniDV, although some early models supported full-size VHS and Betamax. In the 21st century, digital recording became the norm while videocassette tapes dwindled away gradually; tapeless camcorders use other storage media such as DVDs, or internal flash memory, hard drive, and SD card.[26]

In addition, VCR/Blu-ray combo players exist. These players can support up to six formats: VHS, CD (including VCD), DVD, Blu-ray, USB flash drives and SD cards.

See also

- Telerecording

- TV/VCR combo

- VCR/DVD combo

- Kinescope

- Write protection

- Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc.

- Dew warning

- Blu-ray Disc

References

- SMPTE Journal: Publication of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers, Volume 96, Issues 1-6; Volume 96, page 256, Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers

- "Ampex VRX-1000 – The First Commercial Videotape Recorder in 1956". Cedmagic.com. 14 April 1956. Retrieved 31 May 2010.

- Richard N. Diehl. "Labguy'S World: The Birth Of Video Recording". Labguysworld.com. Retrieved 31 May 2010.

- "50 Years of the Video Cassette Recorder". www.wipo.int. November 2006.

- "The History of Video and Related Innovations". inventors.about.com.

- World's First Helical Scan Video Tape Recorder, Toshiba

- "Sony Global - Sony History". Sony.net. Archived from the original on 7 September 2009. Retrieved 31 May 2010.

- "The quest for home video: Telcan home video recorder". Terramedia.co.uk. 22 October 2001. Retrieved 31 May 2010.

- "Total Rewind". Total Rewind. Retrieved 31 May 2010.

- "BBC History". BBC.co.uk. 24 June 1963. Retrieved 31 May 2010.

- "Sony CV Series Video". Smecc.org. Retrieved 31 May 2010.

- "Trends in the Semiconductor Industry: 1970s". Semiconductor History Museum of Japan. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- Howe, Tom. "Cartrivision - The First VCR with Prerecorded Sale/Rental Tapes in 1972". Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- Sony sold 15,000 U-matic machines in the U.S. in its first year. "Television on a Disk", Time, 18 September 1972. Nicknamed in latter years "Betamax-VHS" The U-matic vcr Format was manufactured to as soon as 1990 arrived (VP means video player, VO means recorder "Video Office")

- "VCR". www.computerhope.com.

- "In Pictures | Thatcher years in graphics". BBC News. 18 November 2005. p. 15. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- "The Betamax vs VHS Format War, Author: Dave Owen, Originally published: 2005". Mediacollege.com. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- "Why is Beta better". Web.archive.org. 8 June 2007. Archived from the original on 8 June 2007. Retrieved 31 May 2010.

- "JVC HR3300". Rewind museum company 2010. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- "Jack Valenti Testimony at 1982 House Hearing on Home Recording of Copyrighted Works". Cryptome.org. Retrieved 2010-05-31.

- "VCR eats tapes". The Sci.Electronics.Repair (S.E.R) FAQ. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- Samuel Gibbs (22 July 2016). "VHS is dead, but at least it outlived Betamax tapes by nine months". Guardian. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- "VHS, Beloved Home Video Format, Dies at 40". ScreenCrush. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- SquareTrade. "Panasonic DMP-BD70V Blu-ray Disc/VHS Multimedia Player: Electronics". Amazon.com. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- stason.org, Stas Bekman: stas (at). "14.18 Is VHS Hi-Fi sound perfect? Is Beta Hi-Fi sound perfect?". Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- "CES 2011 Camcorder Coverage". CamcorderInfo.com. Archived from the original on 2 January 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Video recorders. |