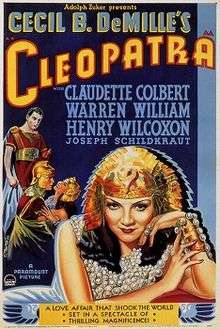

Cleopatra (1934 film)

Cleopatra is a 1934 American epic film directed by Cecil B. DeMille and distributed by Paramount Pictures. A retelling of the story of Cleopatra VII of Egypt, the screenplay was written by Waldemar Young and Vincent Lawrence and was based on Bartlett Cormack's adaptation of historical material.[2] Claudette Colbert stars as Cleopatra, Warren William as Julius Caesar, and Henry Wilcoxon as Mark Antony.

| Cleopatra | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Cecil B. DeMille |

| Produced by | Cecil B. DeMille |

| Written by | Waldemar Young Vincent Lawrence Bartlett Cormack (adaptation: historical material) |

| Starring | Claudette Colbert Warren William Henry Wilcoxon |

| Music by | Rudolph G. Kopp Milan Roder (uncredited) |

| Cinematography | Victor Milner |

| Edited by | Anne Bauchens (uncredited) |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date | August 16, 1934[1] |

Running time | 100 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $842,908[2] |

| Box office | $1,929,161[2] |

Nominated for five Academy Awards, Cleopatra was the first DeMille film to receive a nomination for Best Picture.[3] Victor Milner won the Academy Award for Best Cinematography.[4]

Plot

In 48 BC, Cleopatra vies with her brother Ptolemy for control of Egypt. Pothinos (Leonard Mudie) kidnaps her and Apollodorus (Irving Pichel) and strands them in the desert. When Pothinos informs Julius Caesar that the queen has fled the country, Caesar is ready to sign an agreement with Ptolemy when Apollodorus appears, bearing a gift carpet for the Roman. When Apollodorus unrolls it, Cleopatra emerges, much to Pothinos' surprise. He tries to deny who she is. However, Caesar sees through the deception and Cleopatra soon beguiles Caesar with the prospect of the riches of not only Egypt, but also India. Later, when they are seemingly alone, she spots a sandal peeking out from underneath a curtain and thrusts a spear into the hidden Pothinos, foiling his assassination attempt. Caesar makes Cleopatra the sole ruler of Egypt, and begins an affair with her.

Caesar eventually returns to Rome with Cleopatra to the cheers of the masses, but Roman unease is directed at Cleopatra. Cassius (Ian Maclaren), Casca (Edwin Maxwell), Brutus (Arthur Hohl) and other powerful Romans become disgruntled, rightly suspecting that he intends to abolish the Roman Republic and make himself emperor, with Cleopatra as his empress (after divorcing Calpurnia, played by Gertrude Michael). Ignoring the forebodings of Calpurnia, Cleopatra, and a soothsayer (Harry Beresford) who warns him about the Ides of March, Caesar goes to announce his intentions to the Senate. Before he can do so, he is assassinated.

Cleopatra is heartbroken at the news. At first, she wants to go to him, but Apollodorus tells her that Caesar did not love her, only her power and wealth, and that Egypt needs her. They return home.

Bitter rivals Marc Antony and Octavian (Ian Keith) are named co-rulers of Rome. Antony, disdainful of women, invites Cleopatra to meet with him in Tarsus, intending to bring her back to Rome as a captive. Enobarbus (C. Aubrey Smith), his close friend, warns Antony against meeting Cleopatra, but he goes anyway. She entices him to her barge and throws a party with many exotic animals and beautiful dancers, and soon seduces him. Together, they sail to Egypt.

King Herod (Joseph Schildkraut), who has secretly allied himself with Octavian, visits the lovers. He informs Cleopatra privately that Rome and Octavian can be appeased if Antony were to be poisoned. Herod also tells Antony the same thing, with the roles reversed. Antony laughs off his suggestion, but a reluctant Cleopatra, reminded of her duty to Egypt by Apollodorus, tests a poison on a condemned murderer (Edgar Dearing) to see how it works. Before Antony can drink the fatal wine, however, they receive news that Octavian has declared war.

Antony orders his generals and legions to gather, but Enobarbus informs him that they have all deserted out of loyalty to Rome. Enobarbus tells his comrade that he can wrest control of Rome away from Octavian by having Cleopatra killed, but Antony refuses to consider it. Enobarbus bids Antony goodbye, as he will not fight for an Egyptian queen against Rome. A short montage sequence shows the fighting between the forces of Antony and Octavian, ending in the naval Battle of Actium.

Antony fights on with the Egyptian army, and is defeated. Octavian and his soldiers surround and besiege Antony and Cleopatra. Antony is mocked when he offers to fight them one by one. Without his knowledge, Cleopatra opens the gate and offers to cede Egypt in return for Antony's life in exile, but Octavian turns her down. Meanwhile, Antony believes that she has deserted him for his rival and stabs himself. When Cleopatra returns, she is heartbroken to find him dying. They reconcile before he perishes. Then, with the gates breached, Cleopatra kills herself with a poisonous snake and is found sitting on her throne, dead.

Cast

The closing credits list 32 actors and the names of their characters:

|

|

Production

The shoot was a difficult one due to Colbert contracting appendicitis on the set of her previous film, Four Frightened People, leaving her only able to stand for a few minutes at a time. Heavy costumes complicated matters further.[6] Due to Colbert's fear of snakes, DeMille put off her death scene for as long as possible. At the time of shooting, he walked onto the set with a boa constrictor wrapped around his neck and handed Colbert a tiny garden snake.[6]

On July 1, 1934,[7] the Motion Picture Production Code began to be rigidly enforced and expanded by Joseph Breen. Talkie films made before that date are generally referred to as "pre-Code" films. However, DeMille was able to get away with using more risqué imagery than he would be able to do in his later productions. He opens the film with an apparently naked, but strategically lit slave girl holding up an incense burner in each hand as the title appears on screen.

The film is also memorable for the sumptuous art deco look of its sets (by Hans Dreier) and costumes (by Travis Banton), the atmospheric music composed and conducted by Rudolph George Kopp, and for DeMille's legendary set piece of Cleopatra's seduction of Antony, which takes place on Cleopatra's barge. Colbert later said, "DeMille's films were special: somehow when he put everything together, there was a special kind of glamour and sincerity."[8]

Release

Cleopatra received its world premiere on August 16, 1934 at the Paramount Theatre in New York City.[9] The premiere audience, which gave the film an ovation, included social leaders, diplomats, and famous stars of stage and film.[9] In its first week at the Paramount, the film set an annual record with 110,383 admissions.[10]

Reception

Mordaunt Hall of The New York Times called it "one of the director's most ambitious spectacles" and singled out Wilcoxon's performance as "excellent, especially in the more dramatic sequences."[11] Film Daily called it a "sumptuous historical drama" with a "strong cast" and "good entertainment values".[12] John Mosher of The New Yorker wrote that "Even as extravaganza it's moderate", and called the dialogue "the worst I have ever heard in the talkies."[13] Variety agreed that "Often the lines drew titters that are not being angled for", but maintained, "Photographically the picture is superb."[14]

In his Movie Guide, film critic Leonard Maltin gave Cleopatra 3.5 out of 4 stars and wrote, "Opulent DeMille version of Cleopatra doesn't date badly, stands out as one of his most intelligent films, thanks in large part to fine performances by all."[15]

The film was one of Paramount's biggest hits of the year.[16]

Accolades

At the 7th Academy Awards in 1935, Cleopatra won for Best Cinematography (Victor Milner).[4] It was nominated for four more awards: Outstanding Production (Paramount), Best Assistant Director (Cullen Tate), Best Film Editing (Anne Bauchens), and Best Sound Recording (Franklin Hansen).[4] In the January 1935 issue of The New Movie Magazine, Claudette Colbert's performance in Cleopatra was named the "Movie Highlight of the Year" for August 1934,[17] the month in which the film premiered.

In 2002, the American Film Institute nominated Cleopatra for the AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions list.[18]

Home media

Cleopatra, along with The Sign of the Cross, Four Frightened People, The Crusades and Union Pacific, was released on DVD in 2006 by Universal Studios as part of the five-disc box set "The Cecil B. DeMille Collection".[19]

It has been released for home viewing several times in the United States of America, including a 75th anniversary DVD edition in 2009 by Universal Studios Home Entertainment.[20]

In the United Kingdom, Cleopatra was released in a Dual Format DVD and Blu-ray edition on September 24, 2012 by Eureka as part of their Masters of Cinema range.[21]

On April 10, 2018, Universal Pictures Home Entertainment released the film on Blu-ray.[22]

References

- "Calendar of Current Releases". Variety. New York. August 28, 1934. p. 23. Retrieved June 6, 2018.

- Birchard 2004, p. 275.

- Orrison, Katherine (1999). Written in Stone: Making Cecil B. DeMille's Epic The Ten Commandments. Vestal Press. p. 3. ISBN 9781461734819.

- "The 7th Academy Awards (1935)". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- "Claudette Colbert, 80 and Busy". The New York Times. April 16, 1984. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- McGillicuddy, Genevieve. "Cleopatra (1934)". Turner Classic Movies. Turner Entertainment. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- Birchard 2004, p. 276.

- Kakutani, Michiko (November 16, 1979). "Claudette Colbert Still Tells DeMille Stories". The New York Times. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- "Ovation for "Cleopatra" at Swanky B'way Premiere". The Film Daily. LXVI (40): 1, 8. August 17, 1934.

- "110,383 See "Cleopatra" in First Week". The Film Daily. LXVI (47): 1. August 25, 1934.

- Hall, Mordaunt (August 17, 1934). "Movie Review – Cleopatra". The New York Times. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- "Reviews of Features and Shorts". Film Daily. New York: Wid's Films and Film Folk, Inc. July 25, 1934. p. 13.

- Mosher, John C. (August 25, 1934). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. pp. 42, 44.

- "Cleopatra". Variety. New York. August 21, 1934. p. 17.

- Maltin, Leonard (2017). Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide: The Modern Era, Previously Published as Leonard Maltin's 2015 Movie Guide. Penguin. p. 260. ISBN 9780525536314.

- Churchill, Douglas W. The Year in Hollywood: 1934 May Be Remembered as the Beginning of the Sweetness-and-Light Era (gate locked); New York Times 30 Dec 1934: X5. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

- "Movie Highlights of the Year". The New Movie Magazine. XI (1): 37, 59. January 1935.

- "America's Greatest Love Stories 400 Nominated Films" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- Kehr, Dave (May 23, 2006). "New DVD's: A Box of DeMille". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- Chaney, Jen (April 9, 2009). "A Pair of DVDs From a 'Loose' Era". Washington Post. Retrieved April 12, 2009.

- "Masters of Cinema - Eureka". eurekavideo.co.uk.

- "DeMille's Cleopatra Coming to Blu-ray in April -- 3 Day Special Price". ClassicFlix. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

Bibliography

- Birchard, Robert S. (2004). Cecil B. DeMille's Hollywood. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813123240.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eyman, Scott (2010). Empire of Dreams: The Epic Life of Cecil B. DeMille. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781439180419.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cleopatra (1934 film). |