Lepontic language

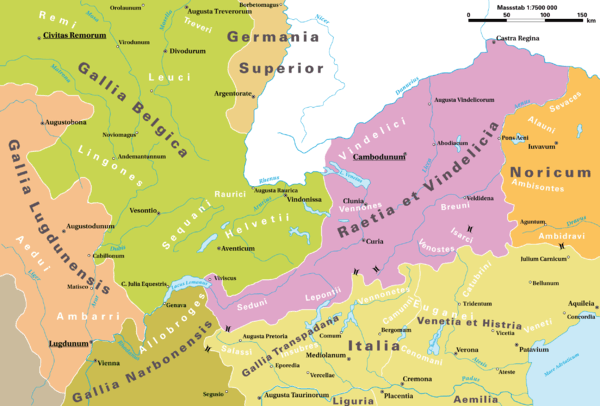

Lepontic is an ancient Alpine Celtic language that was spoken in parts of Rhaetia and Cisalpine Gaul (what is now Northern Italy) between 550 and 100 BC. Lepontic is attested in inscriptions found in an area centered on Lugano, Switzerland, and including the Lake Como and Lake Maggiore areas of Italy.

| Lepontic | |

|---|---|

| Region | Cisalpine Gaul |

| Ethnicity | Lepontii |

| Era | attested 550–100 BC |

Indo-European

| |

| Lugano alphabet (a variant of Old Italic) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | xlp |

xlp | |

| Glottolog | lepo1240[1] |

.png)

Lepontic is a Celtic language.[2][3] While some recent scholarship (e.g. Eska 1998) has tended to consider it simply as an early outlying form of Gaulish and closely akin to other, later attestations of Gaulish in Italy (Cisalpine Gaulish), some scholars (notably Lejeune 1971) continue to view it as a distinct Continental Celtic language.[2][4][5] Within this latter view, the earlier inscriptions found within a 50 km radius of Lugano are considered Lepontic, while the later ones, to the immediate south of this area, are considered Cisalpine Gaulish.[6][7]

Lepontic was assimilated first by Gaulish, with the settlement of Gaulish tribes north of the River Po, and then by Latin, after the Roman Republic gained control over Gallia Cisalpina during the late 2nd and 1st century BC.

Classification

Some scholars view[5] (e.g. Lejeune 1971, Koch 2008) Lepontic as a distinct Continental Celtic language.[2][3] Other scholars (e.g. Evans 1992, Solinas 1995, Eska 1996, McCone 1996, Matasovic 2009)[8][9] consider it as an early form of Cisalpine Gaulish (or Cisalpine Celtic) and thus a dialect of the Gaulish language. An earlier view, which was prevalent for most of the 20th century and until about 1970, regarded Lepontic as a "para-Celtic" western Indo-European language, akin to but not part of Celtic, possibly related to Ligurian (Whatmough 1933 and Pisani 1964). However, Ligurian itself has been considered akin to, but not descended from, Common Celtic, see Kruta 1991 and Stifter 2008.[10][11]

Referring to linguistic arguments as well as archaeological evidence, Schumacher even considers Lepontic a primary branch of Celtic, perhaps even the first language to diverge from Proto-Celtic.[5] In any case, the Lepontic inscriptions are the earliest attestation of any form of Celtic.

Language

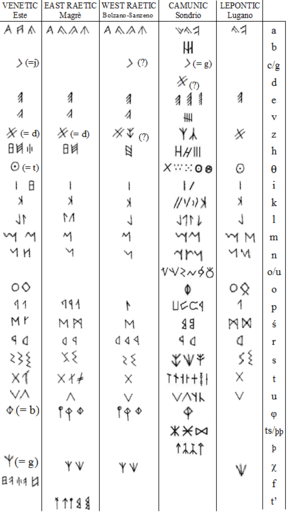

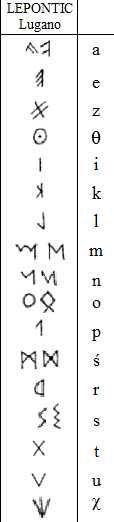

The alphabet

The alphabet of Lugano, based on inscriptions found in northern Italy and Canton Ticino, was used to record Lepontic inscriptions, among the oldest testimonies of any Celtic language, in use from the 7th to the 5th centuries BC. The alphabet has 18 letters, derived from the archaic Etruscan alphabet

The alphabet does not distinguish voiced and unvoiced occlusives, i.e. P represents /b/ or /p/, T is for /t/ or /d/, and K for /g/ or /k/. Z is probably for /ts/. U /u/ and V /w/ are distinguished. Θ is probably for /t/ and X for /g/. There are claims of a related script discovered in Glozel.

Corpus

Lepontic is known from around 140 inscriptions written in the alphabet of Lugano, one of five main Northern Italic alphabets derived from the Etruscan alphabet. Similar scripts were used for writing the Rhaetic and Venetic languages and the Germanic runic alphabets probably derive from a script belonging to this group.

The grouping of all inscriptions written in the alphabet of Lugano into a single language is disputed. Indeed, it was not uncommon in antiquity for a given alphabet to be used to write multiple languages. And, in fact, the alphabet of Lugano was used in the coinage of other Alpine tribes, such as the Salassi, Salluvii, and Cavares (Whatmough 1933, Lejeune 1971).

While many of the later inscriptions clearly appear to be written in Cisalpine Gaulish, some, including all of the older ones, are said to be in an indigenous language distinct from Gaulish and known as Lepontic. Until the publication of Lejeune 1971, this Lepontic language was regarded as a pre-Celtic language, possibly related to Ligurian (Whatmough 1933, Pisani 1964). Following Lejeune 1971, the consensus view became that Lepontic should be classified as a Celtic language, albeit possibly as divergent as Celtiberian, and in any case quite distinct from Cisalpine Gaulish (Lejeune 1971, Kruta 1991, Stifter 2008).[10][11] Some have gone further, considering Lepontic and Cisalpine Gaulish essentially one and the same (Eska 1998). However, an analysis of the geographic distribution of the inscriptions shows that the Cisalpine Gaulish inscriptions are later and from an area to the south of the earlier (Lepontic) inscriptions, with which they display significant differences as well as similarities.[11]

While the language is named after the tribe of the Lepontii, which occupied portions of ancient Rhaetia, specifically an Alpine area straddling modern Switzerland and Italy and bordering Cisalpine Gaul, the term is currently used by some Celticists (e.g. Eska 1998) to apply to all Celtic dialects of ancient Italy. This usage is disputed by those who continue to view the Lepontii as one of several indigenous pre-Roman tribes of the Alps, quite distinct from the Gauls who invaded the plains of Northern Italy in historical times.

The older Lepontic inscriptions date back to before the 5th century BC, the item from Castelletto Ticino being dated at the 6th century BC and that from Sesto Calende possibly being from the 7th century BC (Prosdocimi, 1991). The people who made these inscriptions are nowadays identified with the Golasecca culture, a Celtic culture in northern Italy (De Marinis 1991, Kruta 1991 and Stifter 2008).[10][11] The extinction date for Lepontic is only inferred by the absence of later inscriptions.

Texts

See also

References

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Lepontic". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- LinguistList: Lepontic

- John T. Koch (ed.) Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia ABC-CLIO (2005) ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0

- Koch 2006; 1142.

- Schumacher, Stefan; Schulze-Thulin, Britta; aan de Wiel, Caroline (2004). Die keltischen Primärverben. Ein vergleichendes, etymologisches und morphologisches Lexikon (in German). Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachen und Kulturen der Universität Innsbruck. pp. 84–85. ISBN 3-85124-692-6.

- Kruta, Venceslas (1991). The Celts. Thames and Hudson. p. 55.

- Stifter, David (2008). Old Celtic Languages (PDF). p. 12.

- Pinault, Georges-Jean (2007). Gaulois et celtique continental (in French). Librairie Droz. p. 375. ISBN 9782600013376.

- Matasović, Ranko (2009). Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic. Brill. pp. 13 & 16. ISBN 9789004173361.

- Kruta, Venceslas (1991). The Celts. Thames and Hudson. pp. 52–56.

- Stifter, David (2008). Old Celtic Languages (PDF). pp. 24–37.

Sources

- De Marinis, R.C. (1991). "I Celti Golasecchiani". In Multiple Authors, I Celti, Bompiani.

- Eska, J. F. (1998). "The linguistic position of Lepontic". In Proceedings of the twenty-fourth annual meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society vol. 2, Special session on Indo-European subgrouping and internal relations (February 14, 1998), ed. B. K. Bergin, M. C. Plauché, and A. C. Bailey, 2–11. Berkeley: Berkeley Linguistics Society.

- Eska, J. F., and D. E. Evans. (1993). "Continental Celtic". In The Celtic Languages, ed. M. J. Ball, 26–63. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-01035-7.

- Gambari, F. M.; G. Colonna (1988). "Il bicchiere con iscrizione arcaica de Castelletto Ticino e l'adozione della scrittura nell'Italia nord-occidentale". Studi Etruschi. 54: 119–64.

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO.

- Lejeune, M. (1970–71). "Documents gaulois et para-gaulois de Cisalpine". Études Celtiques. 12: 357–500.

- Lejeune, M. (1971). Lepontica. Paris: Société d'Éditions 'Les Belles Lettres'.

- Lejeune, M. (1978). "Vues présentes sur le celtique ancien". Académie Royale de Belgique, Bulletin de la Classe des Lettres et des Sciences morales et politiques. 64: 108–21.

- Lejeune, M. (1988). Recueil des inscriptions gauloises: II.1 Textes gallo-étrusques. Textes gallo-latins sur pierre. Paris: CNRS.

- Pisani, V. (1964). Le lingue dell'Italia antica oltre il latino (2nd ed.). Turin: Rosenberg & Sellier.

- Prosdocimi, A.L. (1991). "Lingua e scrittura dei primi Celti". In Multiple Authors, I Celti, pp. 50–60, Bompiani.

- Tibiletti Bruno, M. G. (1978). "Ligure, leponzio e gallico". In Popoli e civiltà dell'Italia antica vi, Lingue e dialetti, ed. A. L. Prosdocimi, 129–208. Rome: Biblioteca di Storia Patria.

- Tibiletti Bruno, M. G. (1981). "Le iscrizioni celtiche d'Italia". In I Celti d'Italia, ed. E. Campanile, 157–207. Pisa: Giardini.

- Whatmough, J. (1933). The Prae-Italic Dialects of Italy, vol. 2, "The Raetic, Lepontic, Gallic, East-Italic, Messapic and Sicel Inscriptions", Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press

External links

- Lexicon Leponticum, by David Stifter, Martin Braun and Michela Vignoli, University of Vienna – free online lexicon and corpus

- Francesca Ciurli (translation revised by Melanie Rockenhaus) (2008–2017). "Celtic, Lepontic - About 7th – 6th century B.C". Mnamon - Ancient Writing Systems in the Mediterranean. Scuola Normale Superiore. Retrieved 15 October 2018.CS1 maint: date format (link)