Venetic language

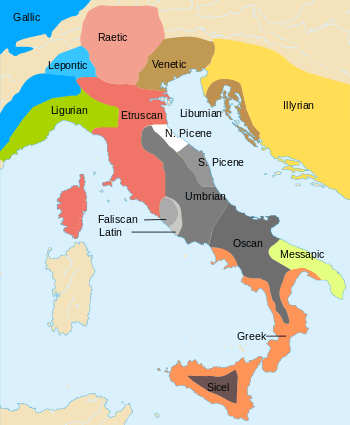

Venetic is an extinct Indo-European language, usually classified into the Italic subgroup, that was spoken by the Veneti people in ancient times in northeast Italy (Veneto and Friuli) and part of modern Slovenia, between the Po River delta and the southern fringe of the Alps.[3][1][4]

| Venetic | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Italy |

| Region | Veneto |

| Ethnicity | Adriatic Veneti |

| Era | attested 6th–1st century BC[1] |

Indo-European

| |

| Old Italic (Venetic alphabet) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | xve |

xve | |

| Glottolog | vene1257[2] |

The language is attested by over 300 short inscriptions dating from the 6th to the 1st century BC. Its speakers are identified with the ancient people called Veneti by the Romans and Enetoi by the Greeks. It became extinct around the 1st century when the local inhabitants were assimilated into the Roman sphere. Inscriptions dedicating offerings to Reitia are one of the chief sources of knowledge of the Venetic language.[5]

Venetic should not be confused with Venetian, a Romance language spoken in the same general region, which developed from Vulgar Latin, another Italic language.

Linguistic classification

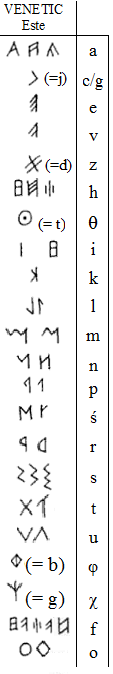

Venetic is a centum language. The inscriptions use a variety of the Northern Italic alphabet, similar to the Etruscan alphabet.

The exact relationship of Venetic to other Indo-European languages is still being investigated, but the majority of scholars agree that Venetic, aside from Liburnian, shared some similarities with the Italic languages and so is sometimes classified as Italic. However, since it also shared similarities with other Western Indo-European branches (particularly Celtic languages and Germanic languages), some linguists prefer to consider it an independent Indo-European language. Venetic may also have been related to the Illyrian languages once spoken in the western Balkans, though the theory that Illyrian and Venetic were closely related is debated by current scholarship.

While some scholars consider Venetic plainly an Italic language, more closely related to the Osco-Umbrian languages than to Latin, many authorities suggest, in view of the divergent verbal system, that Venetic was not part of Italic proper, but split off from the core of Italic early.[6]

Recent research has concluded that Venetic was a relatively archaic language significantly similar to Celtic, on the basis of morphology, while it occupied an intermediate position between Celtic and Italic, on the basis phonology. However these phonological similarities may have arisen as an areal phenomenon.[7] Phonological similarities to Rhaetian have also been pointed out.[8]

Fate

During the period of Latin-Venetic bilingual inscriptions in the Roman script, i.e. 150–50 BCE, Venetic becomes flooded with Latin loanwords. The shift from Venetic to Latin resulting in language death is thought by scholarship to have already been well under way by that time.[9]

Features

Venetic had about six or even seven noun cases and four conjugations (similar to Latin). About 60 words are known, but some were borrowed from Latin (liber.tos. < libertus) or Etruscan. Many of them show a clear Indo-European origin, such as vhraterei < PIE *bʰréh₂trey = to the brother.

Phonology

In Venetic, PIE stops *bʰ, *dʰ and *gʰ developed to /f/, /f/ and /h/, respectively, in word-initial position (as in Latin and Osco-Umbrian), but to /b/, /d/ and /g/, respectively, in word-internal intervowel position (as in Latin). For Venetic, at least the developments of *bʰ and *dʰ are clearly attested. Faliscan and Osco-Umbrian have /f/, /f/ and /h/ internally as well.

There are also indications of the developments of PIE *kʷ > kv, *gʷ- > w- and PIE *gʷʰ- > f- in Venetic, the latter two being parallel to Latin; as well as the regressive assimilation of the PIE sequence *p...kʷ... > *kʷ...kʷ..., a feature also found in Italic and Celtic.[10]:p.141

Language sample

A sample inscription in Venetic, found on a bronze nail at Este (Es 45):[3]:p.149

- Venetic: Mego donasto śainatei Reitiiai porai Egeotora Aimoi ke louderobos

- Latin (literal): me donavit sanatrici Reitiae bonae Egetora [pro] Aemo liberis-que

- English: Egetora gave me to Good Reitia the Healer on behalf of Aemus and the children

Another inscription, found on a situla (vessel such as an urn or bucket) at Cadore (Ca 4 Valle):[3]:p.464

- Venetic: eik Goltanos doto louderai Kanei

- Latin (literal): hoc Goltanus dedit liberae Cani

- English: Goltanus sacrificed this for the free Kanis

Scholarship

The most prominent scholars who have deciphered Venetic inscriptions or otherwise contributed to the knowledge of the Venetic language are Carl Eugen Pauli,[11] Hans Krahe,[12] Giovanni Battista Pellegrini,[3] Aldo Luigi Prosdocimi,[3][13][14] and Michel Lejeune.[10] Recent contributors include Loredana Calzavara Capuis[15] and Anna Maria Chieco Bianchi.[16]

See also

References

- Wallace, Rex (2004). Venetic in Roger D. Woodard (ed.), The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World’s Ancient Languages, University of Cambridge, pp. 840-856. ISBN 0-521-56256-2 Online version

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Venetic". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Giovanni Battista Pellegrini; Aldo Luigi Prosdocimi (1967). La Lingua Venetica: I- Le iscrizioni; II- Studi. Padova: Istituto di glottologia dell'Università di Padova.

- The Illyrians by J. J. Wilkes Page 77 ISBN 0-631-19807-5

- Cambridge Ebooks, The Ancient Languages of Europe

- de Melo, Wolfgang David Cirilo (2007). "The sigmatic future and the genetic affiliation of Venetic: Latin faxō "I shall make" and Venetic vha.g.s.to "he made"". Transactions of the Philological Society. 105 (105): 1–21. doi:10.1111/j.1467-968X.2007.00172.x.

- Gvozdanović, Jadranka (2012). "On the linguistic classification of Venetic. In Journal of Language Relationship." p. 34.

- Silvestri, M.; Tomezzoli, G. (2007). Linguistic distances between Rhaetian, Venetic, Latin and Slovenian languages (PDF). Proc. Int'l Topical Conf. Origin of Europeans. pp. 184–190.

- Woodard, Roger D., ed. The ancient languages of Europe. Cambridge University Press, 2008. Page 139.

- Michel Lejeune (1974). Manuel de la langue vénète. Heidelberg: Carl Winter - Universitätsverlag.

- Carl Eugen Pauli (1885–94). Altitalische Forschungen. Leipzig: J.A. Barth.

- Hans Krahe (1954). Sprache und Vorzeit : europäische Vorgeschichte nach dem Zeugnis der Sprache. Heidelberg: Quelle & Meyer.

- Aldo Luigi Prosdocimi (2002), Veneti, Eneti, Euganei, Ateste.

- Aldo Luigi Prosdocimi (2002).Trasmissioni alfabetiche e insegnamento della scrittura, in AKEO. I tempi della scrittura. Veneti antichi: alfabeti e documenti, (Catalogue of an exposition at Montebelluna, 12/2001-05/2002). Montebelluna, pp.25-38.

- Selected bibliography of Loredana Calzavara Capuis Archived 2005-08-06 at Archive.today

- Anna Maria Chieco Bianchi; et al. (1988). Italia: omnium terrarum alumna: la civiltà dei Veneti, Reti, Liguri, Celti, Piceni, Umbri, Latini, Campani e Iapigi. Milano: Scheiwiller.

Further reading

- Beeler, Madison Scott. 1949. The Venetic Language. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press.

- Gambacurta, Giovanna. I Celti e il Veneto. In: Etudes Celtiques, vol. 39, 2013. pp. 31-40. doi:10.3406/ecelt.2013.2396

- Gérard, Raphaël. Observations sur les inscriptions vénètes de Pannonie. In: Revue belge de philologie et d'histoire, tome 79, fasc. 1, 2001. Antiquité - Oudheid. pp. 39-56. doi:10.3406/rbph.2001.4506

- Prósper, Blanca Maria. "The Venetic Inscription from Monte Manicola and Three termini publici from Padua: A Reappraisal". In: Journal of Indo-European Studies (JIES). Volume 46, Number 1 & 2, Spring/Summer 2018. pp. 1-61.

- Šavli, Jožef, Matej Bor, Ivan Tomažič, and Anton Škerbinc. 1996. Veneti: First Builders of European Community: Tracing the History and Language of Early Ancestors of Slovenes. Wien: Editiones Veneti.

External links

| Library resources about Venetic language |

- Víteliú: The Languages of Ancient Italy.

- Venetic inscriptions Adolfo Zavaroni.

- Indo-European database: The Venetic language Cyril Babaev.

- Italic languages - Additional reading Encyclopædia Britannica.