Laurel Hill Cemetery

Laurel Hill Cemetery is a historic garden or rural cemetery in the East Falls neighborhood of Philadelphia. Founded in 1836, it was the second major rural cemetery in the United States after Mount Auburn Cemetery in Boston, Massachusetts.

Laurel Hill Cemetery | |

_HABS314296cv.jpg) Laurel Hill Cemetery Gatehouse | |

| |

| Location | 3822 Ridge Avenue, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°00′14″N 75°11′15″W |

| Built | 1836-1839[1] |

| Architect | John Notman[1] |

| Architectural style | Exotic Revival, Gothic, Classical Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 77001185[2] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 28, 1977 |

| Designated PHMC | May 20, 2000[3] |

The cemetery is 74-acre (300,000 m2) in size and overlooks the Schuylkill River. The cemetery grew to its current size through the purchase of four land parcels between 1836 and 1861. It contains over 11,000 family lots and more than 33,000 graves, many adorned with grand marble and granite funerary monuments, elaborately sculpted hillside tombs and mausoleums.[4]

In 1977, Laurel Hill Cemetery was listed on the National Register of Historic Places[5] and in 1998, became the first cemetery in the United States to be designated a National Historic Landmark.[6][7]

History

The cemetery was founded in 1836 by John Jay Smith[8], a librarian and editor with interests in horticulture and real estate, who was distressed at the way his deceased daughter was interred at the Arch Street Meeting House burial ground in Philadelphia. Smith wrote, "Philadelphia should have a rural cemetery on dry ground, where feelings should not be harrowed by viewing the bodies of beloved relatives plunged into mud and water."[9]

Smith joined forces with other prominent Philadelphia citizens including Benjamin Wood Richards, William Strickland and Nathan Dunn to form the Laurel Hill Cemetery Company and create a rural cemetery three miles north of the Philadelphia border on the east bank of the Schuylkill River.[10] The group considered several locations but decided on the 32 acre[4] former estate of businessman Joseph Sims[1] known as "Laurel" or "Laurel Hill".[11] The location was viewed as a haven from urban expansion and a respite from the increasingly industrialized city center. The city later grew past Laurel Hill, but the cemetery retained its rural character.

Designs for the cemetery were submitted by William Strickland and Thomas Ustick Walter[12] but the commission selected Scottish-American architect John Notman.[1] Notman's designs incorporated the topography of the location and included a string of terraces that descended to the river.[12] The cemetery was developed and completed between 1836 and 1839.[1] Notman designed the gatehouse which consists of a massive Roman arch surrounded by an imposing classical colonnade and topped with a large ornamental urn. A large Gothic Revival style chapel was built on the grounds but removed in the 1880s to make room for additional graves.[12]

In 1836, the cemetery purchased a group of three sandstone statues from Scottish sculptor James Thom, known as Old Mortality. The statues were placed in a small enclosure in the central courtyard directly in front of the main gatehouse. The statues are based on a tale by Sir Walter Scott and depict Scott talking to Old Mortality, an elderly man who traveled through the Scottish Highlands re-carving weathered tombstones, along with his pony.[13] A plaster bust of the artist, James Thom, was added to the display in 1872. The owners of the cemetery intended to equate the mission of Old Mortality with their own - to keep the cemetery in perpetual care so future generations may remember the deceased.[4]

To increase its cachet, the cemetery's organizers had the remains of several famous Revolutionary War figures moved there, including Continental Congress secretary Charles Thomson; Declaration of Independence signer Thomas McKean; Philadelphia war veteran and shipbuilder Jehu Eyre; Hugh Mercer, hero of the Battle of Princeton; and David Rittenhouse, first director of the U.S. Mint.

Many of the elaborate funerary monuments were designed by notable artists and architects including Alexander Milne Calder, Alexander Stirling Calder, Harriet Whitney Frishmuth and William Strickland. The monument design styles include Classical Revival, Gothic Revival and Egyptian Revival made out of materials such as marble, granite, cast-iron and sandstone.

From its inception, Laurel Hill was intended as a civic institution designed for public use. In an era before public parks, museums and arboretums, it was a multi-purpose cultural attraction[14] where the general public could experience the art and refinement previously known only to the wealthy.[15] By the 1840s, Laurel Hill was an immensely popular destination and required tickets for admission. Writer Andrew Jackson Downing reported "nearly 30,000 persons…entered the gates between April and December, 1848."

In 1844, due to increasing popularity, Laurel Hill purchased the 27 acre former estate of jurist William Rawle, half a mile south and named it South Laurel Hill.[4] In 1849, a set of iron gates on sandstone piers was built in the southeastern corner of the cemetery and served as a secondary entrance.[4]

In 1855, the Pennsylvania State Assembly authorized the cemetery to purchase an additional 10 acres from Frederick Stoever known as the Stoever Tract. The Yellow Fever Monument was built in this section in 1859 to honor the "Doctors, Druggists and Nurses" who helped fight the epidemic in Portsmouth, Virginia.[16]

In 1860, Laurel Hill Cemetery had an estimated 140,000 people visit annually.[17]

In 1861, the 21-acre estate of George Pepper between the two cemeteries was purchased and named Central Laurel Hill.[4] With these additions, the cemetery reached the current size of approximately 95 acres. A bridge was built over Hunting Park Avenue to connect Central and South Laurel Hill.[18]

The cemetery association restricted who could buy lots and the majority of burials were for white Protestants. The cemetery discouraged unmarried people from buying lots in order to keep the cemetery as a family destination.[19]

During and after the American Civil War, Laurel Hill became the final resting place of hundreds of military figures, including 40 Civil War-era generals. Laurel Hill also became the favored burial place for many of Philadelphia's most prominent political and business figures, including Matthias W. Baldwin, founder of the Baldwin Locomotive Works; Henry Disston, owner of the largest saw factory in the world (the Disston Saw Works); and financier Peter A. B. Widener.[9]

.jpg)

In 1913, a Doric receiving vault made of terra cotta was built in South Laurel Hill near the bridge connecting it to Central Laurel Hill.[4]

By the 1970s, Laurel Hill Cemetery had fallen out of favor as a burial site. Many bodies were re-interred at the more suburban West Laurel Hill Cemetery in nearby Lower Merion, Pennsylvania and the remaining graves suffered neglect, vandalism and crime.[20]

In 1978, the Friends of Laurel Hill Cemetery, a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization, was founded by descendants of John Jay Smith to support the cemetery.[9] The mission of the Friends is to assist the Laurel Hill Cemetery Company in preserving and promoting the historical character of Laurel Hill. The Friends raise funds and seek contributed services; prepare educational and research materials emphasizing the historical, architectural and cultural importance of Laurel Hill Cemetery; and provide tour guides to educate the public. The organization was instrumental in Laurel Hill Cemetery's placement on the National Register of Historic Places in 1977 and designation as a National Historic Landmark in 1998.[9]

In 2013, a 700-pound, 7 foot 2 inch high bronze statue of a Civil War soldier was relocated and rededicated in Laurel Hill Cemetery. The statue was named "The Silent Sentry", cast at the Bureau Brothers Foundry and dedicated in 1883 at Mount Moriah Cemetery. It was originally placed in the Soldiers' Home of Philadelphia burial plot. In 1970, thieves removed the statue from its base and attempted to sell it for scrap metal to a Camden, New Jersey, scrap yard but the scrap dealer notified the authorities.[21] It was recovered and repaired by the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States. In 2013, the statue was relocated and rededicated in Laurel Hill Cemetery.[22]

Laurel Hill Cemetery remains a popular tourist destination with thousands of visitors annually for historical tours, concerts and physical recreation.[23]

Notable burials

- Robert Adams, Jr. (1849–1906), U.S. Congressman

- Hilary Baker (1746–1798), mayor of Philadelphia

- Matthias W. Baldwin (1795–1866), founder of Baldwin Locomotive Works

- Alexander Biddle (1819–1899), Union Army officer in the U.S. Civil War

- Henry H. Bingham (1841-1912), Brevet Brigadier General, Medal of Honor recipient

- Robert Montgomery Bird (1803–1854), American novelist, playwright, and physician

- David Bispham (1857–1921), opera singer

- George A.H. Blake (1810-1884), calvary officer in the U.S. Army

- Charles E. Bohlen (1904–1974), U.S. diplomat

- Francis Bohlen (1868-1942), legal scholar at the University of Pennsylvania

- Henry Bohlen (1810–1862), Civil War Union Brigadier General

- George Henry Boker (1823–1890), poet, playwright, and diplomat

- Joseph Bonnell (1802–1840), West Point graduate, hero of the Texas Revolution

- Adolph E. Borie (1809–1880), Secretary of the Navy

- John Bouvier (1781-1851), jurist and legal lexicographer

- Charles Brown (1797–1883), U.S. Congressman

- George Bryan (1731-1791), colonial Pennsylvania businessman and politician

- Lewis C. Cassidy (1829-1889), Pennsylvania State Attorney General

- John Cassin (1813–1869), ornithologist

- George William Childs (1829–1894), newspaper publisher

- Thomas Clyde (1812-1885), founder of the Clyde Line of steamers

- William P. Clyde (1839–1923), American shipping magnate

- Walter Colton (1797–1851), Chaplain, Alcalde of Monterey, author, publisher of California's first newspaper

- David Conner (1792–1856), U.S. naval officer

- Robert T. Conrad (1810–1858), mayor of Philadelphia

- Joel Cook (1842–1910), U.S. Congressman

- Robert Cornelius (1809–1893), pioneering photographer

- Martha Coston (1826–1904), inventor and businesswoman

- Thomas Jefferson Cram (1804-1883), engineer in the U.S. Corps of Topographical Engineers during the U.S. Civil War

- Samuel W. Crawford (1829–1892), Civil War Union army general

- Alexander Cummings (1810-1879), third Governor of the Territory of Colorado

- Louisa Knapp Curtis (1851–1910), journalist and magazine publisher

- John A. Dahlgren (1809–1870), U.S. naval officer, inventor of the Dahlgren gun

- Ulric Dahlgren (1842-1864), Union Army Captain during the Civil War, namesake of The Dahlgren Affair

- Richard Dale (1756–1826), Revolutionary War naval officer

- Henry Deringer (1786–1868), gunsmith

- Franklin Archibald Dick (1823-1885), attorney

- Hamilton Disston (1844-1896), industrialist and real-estate developer

- Henry Disston (1819–1878), businessman, Disston Saw Works

- Ida Dixon (1854–1916), socialite and first female golf course architect in the United States

- Percival Drayton (1812-1865), U.S. Navy officer

- William Drayton (1776-1846), politician, banker and writer

- William Duane (1760-1835), journalist

- William Duane (1872-1935), physicist

- William J. Duane (1780-1865), U.S. Secretary of the Treasury in 1833

- Stephen Duncan (1787-1867), Mississippi planter and banker

- Robley Dunglison, (1798-1869), "Father of American Physiology"

- Nathan Dunn (1782-1844), businessman and philanthropist

- John Price Durbin (1800-1876), Chaplain of the Senate and president of Dickinson College

- George Meade Easby (1918–2005), great-grandson of General George Meade and a celebrity figure

- George Nicholas Eckert (1802–1865), U.S. Congressman

- William Lukens Elkins (1832-1903), businessman, inventor, art collector

- Charles Ellet, Jr. (1810-1862), civil engineer

- Charles Rivers Ellet (1843-1863), Colonel in the Union Army during the U.S. Civil War

- Alfred L. Elwyn (1804-1884), Physician and pioneer in the management of the mentally disabled

- Jehu Eyre (1738-1781), businessman, veteran of the French and Indian War and American Revolutionary War

- Edwin Henry Fitler (1825-1896), 75th mayor of Philadelphia

- Wilmot E. Fleming (1916-1978), Pennsylvania State Representative and Senator

- Robert H. Foerderer (1860–1903), U.S. Congressman

- Stanely Hamer Ford (1877-1961), U.S. Army General

- Adam Forepaugh (1831–1890), an entrepreneur, businessman, and circus owner

- Anne Francine (1917-1999) actress and cabaret singer

- Samuel Gibbs French (1818–1910), Confederate General has a cenotaph in his family's plot in Laurel Hill.

- Harriet Whitney Frishmuth (1880-1980), sculptor

- Frank Furness (1839–1912), architect, Medal of Honor recipient

- Horace Howard Furness (1833-1912), American Shakespearean scholar

- William Henry Furness (1802-1896), American clergyman, theologian, Transcendentalist, abolitionist, and reformer

- William Gilmore (1895-1969), Olympic rower

- Charles Gilpin (1809-1891), Mayor of Philadelphia from 1851 to 1854

- Henry D. Gilpin (1801–1860), U.S. Attorney General

- Louis Antoine Godey (1804–1878) American editor and publisher

- Thomas Godfrey (1704–1749), optician and inventor

- Sylvanus William Godon (1809-1879), U.S. Naval officer

- Frederick Graff (1775-1847), hydraulic engineer, designer of the Fairmount Water Works

- George Rex Graham (1813-1894), journalist, editor and publisher

- Frederick Gutekunst (1831-1917), prominent photographer

- Henry Schell Hagert (1826–1885), writer, poet, Philadelphia district attorney

- Sarah Josepha Hale (1788–1879), writer, poet

- Frederick Halterman (1831–1907), U.S. Congressman

- James Harper (1780–1873), U.S. Congressman

- Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler (1770–1843), first superintendent of the United States Coast Survey

- Joseph Hemphill (1770–1842), U.S. Congressman

- Alexander Henry (1823–1883), mayor of Philadelphia from 1858 to 1865

- Henry Wilson Hodge (1865–1919), engineer

- Isaac Hull (1773–1843), Commodore, USN, captained Constitution to victory over HMS Guerriere

- Caroline Furness Jayne (1873-1909) American ethnologist

- Owen Jones (1819–1878), U.S. Congressman

- James Juvenal (1874-1942), Olympic rower

- Harry Kalas (1936–2009), Philadelphia Phillies Hall of Fame broadcaster

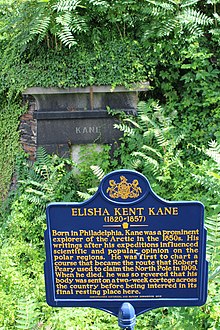

- Elisha Kent Kane (1820–1857), polar explorer

- John K. Kane (1795-1858), U.S. District Judge, Attorney General of Pennsylvania

- William D. Kelley (1814–1890), U.S. Congressman

- Florence Kelley (1859-1932), social and political reformer

- Samuel George King (1816-1899), 73rd mayor of Philadelphia

- William J. Kirkpatrick (1838–1921), composer

- James Kitchenman (1825–1909), textile manufacturer

- Lon Knight (1853-1932), professional baseball player

- Elie A. F. La Vallette (1790-1862), U.S. Navy, one of first rear admirals appointed in 1862

- Henry Charles Lea (1825–1909), historian

- Isaac Lea (1792-1886), conchologist, geologists and publisher

- Mathew Carey Lea (1823-1897), chemist and lawyer

- Michael Leib (1760–1822), U.S. Congressman

- Lewis Charles Levin (1808–1860), U.S. Congressman

- Rachel Lloyd (1839-1900), first U.S. woman to receive Ph.D. in chemistry

- George Horace Lorimer (1868–1937), editor-in-chief of The Saturday Evening Post

- Harry Luff (1856-1916), Major League Baseball player

- Anna Lukens (1844-1917), physician

- Charles Macalester (1798–1873), businessman, Presbyterian Church philanthropist, and namesake of Macalester College

- Alexander Kelly McClure (1828-1909), Pennsylvania State Senator

- George Deardorff McCreary (1846-1915), U.S. Congressman

- Thomas McKean (1734–1817), lawyer and politician, Signer of the Declaration of Independence

- Morton McMichael (1807-1879), editor The Saturday Evening Post, publisher The North American, veteran American Civil War. Mayor of Philadelphia (1866-1869)

- George Gordon Meade (1815–1872), Civil War Union Army Major General, victor at the Battle of Gettysburg

- Charles Delucena Meigs (1792-1869), American obstetrician who opposed anesthesia

- George Wallace Melville (1841-1912), U.S. Navy Admiral, engineer, Arctic explorer, author

- Hugh Mercer (1726–1777), Continental general in the American Revolution

- Samuel Mercer (1799-1862), Union naval officer

- Helen Abbott Michael (1857–1904), plant chemist

- William Millward (1822–1871), U.S. Congressman

- E. Coppée Mitchell (1836-1887), Professor and Dean of the University of Pennsylvania Law School

- John Moffet (1831–1884), U.S. Congressman-elect

- Edward Joy Morris (1815–1881), U.S. Congressman

- James St. Clair Morton (1829-1864), Union Army General in the Civil War

- Samuel George Morton (1799-1855), physician, natural scientist and writer

- Alexander Murray (1755-1821), American officer during the Revolutionary War

- Henry Morris Naglee (1815-1886), Union Army General during the U.S. Civil War

- Charles Naylor (1806–1872), U.S. Congressman

- Matthew Newkirk (1794-1868), businessman, railroad president

- John Notman (1810–1865), architect and designer of Laurel Hill

- Joshua T. Owen (1822-1887), Union brigadier general during the Civil War

- Francis E. Patterson (1821–1862), Union general in the Civil War

- Robert Patterson (1792-1881), Irish-born United States major general during the American Civil War

- Franklin Peale (1795-1870), 3rd chief coiner at United States Mint at Philadelphia

- Titian Peale (1799–1885), artist

- John C. Pemberton (1814–1881), Confederate Civil War General

- Garrett J. Pendergrast (1802–1862), U.S. Civil War naval officer

- Mary Engle Pennington (1872–1952), US scientist and refrigeration pioneer

- Boies Penrose (1860–1921), U.S. Senator

- Charles B. Penrose (1798-1857), Pennsylvania State Senator and Solicitor of the U.S. Treasury

- William Pepper (1843-1898), physician, Provost of University of Pennsylvania, founder Free Library of Philadelphia

- Alonzo Potter (1800-1865), third Episcopal bishop of the Diocese of Pennsylvania

- Samuel J. Randall (1828–1890), U.S. Congressman

- George C. Read (1788-1862), U.S. Naval officer

- Thomas Buchanan Read (1822–1872), American poet, sculptor, portrait-painter

- Joseph Reed (1741–1785), Continental Congressman

- John E. Reyburn (1845–1914), U.S. Congressman, mayor of Philadelphia

- William S. Reyburn (1882–1946), U.S. Congressman

- Benjamin Wood Richards (1797-1851), mayor of Philadelphia

- David Rittenhouse (1732–1796), astronomer, inventor, mathematician, surveyor[27]

- John Robbins (1808–1880), U.S. Congressman

- Moncure Robinson (1802-1891), civil engineer and railroad planner

- Fairman Rogers (1833-1900), civil engineer, educator and philanthropist

- William Ronckendorff (1812-1891), U.S. Naval officer

- Richard Rush (1780–1859), U.S. Attorney General

- John Morin Scott (1789-1858), mayor of Philadelphia from 1841 to 1844

- John Sergeant (1779-1852), U.S. Congressman and 1832 Republican vice presidential nominee

- Jonathan Dickinson Sergeant (1746–1793), Continental Congressman

- Adam Seybert (1773-1825), U.S. Congressman

- George Sharswood (1810-1883) Pennsylvania jurist, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania

- William M. Singerly (1832-1898), businessman and newspaper publishers

- Charles Ferguson Smith (1807–1862), Civil War Union Army General

- John Rowson Smith (1810-1864), panorama painter

- John T. Smith (1801-1864), U.S. Congressman for Pennsylvania's 3rd congressional district from 1843-1845

- Persifor Frazer Smith (1798-1858), U.S. Army officer

- John Batterson Stetson (1830-1906), hat manufacturer, reinterred to West Laurel Hill Cemetery[20]

- William S. Stokely (1823-1902), 72nd mayor of Philadelphia

- Witmer Stone (1866–1939), ornithologist, botanist

- Alfred Sully (1820-1879), soldier, painter, actor

- Thomas Sully (1783–1872), portrait painter

- Charles Thomson (1729–1824), secretary of the Continental Congress

- George Washington Toland (1796–1869), U.S. Congressman

- Laura Matilda Towne (1825-1901), abolitionist and educator

- Levi Twiggs (1793–1847), U.S. Marine Corps officer

- Hector Tyndale (1821-1880), Union general during the American Civil War and protector of the wife of abolitionist John Brown

- Job Roberts Tyson (1803–1858), U.S. Congressman

- Pinkerton R. Vaughn (1841-1866), Medal of Honor recipient

- Richard Vaux (1816–1895), U.S. Congressman, mayor of Philadelphia

- Thomas Ustick Walter (1804–1887), architect

- Joseph Wharton (1826-1909), American industrialist who founded the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, co-founded the Bethlehem Steel company, and was one of the founders of Swarthmore College

- Jonathan Williams (1751–1815), U.S. Army officer and first superintendent of West Point

- Eleanor Elkins Widener, wife of George Widener, survivor of RMS Titanic sinking, responsible for Harry Elkins Widener Library at Harvard University

- Peter A. B. Widener (1834–1915), business tycoon, philanthropist

- Joseph E. Widener (1871–1943), thoroughbred owner/breeder

- John Rhea Barton Willing (1864-1913), music enthusiast and violin collector

- Isaac J. Wistar (1827–1905), Union Army general and penologist

- Owen Wister (1860–1938), novelist, author of The Virginian

- Jacob Zeilin (1806–1880), 7th Commandant of the U.S. Marine Corps, Marine Corps' first general officer

In popular culture

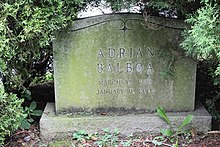

- Tombstones for the fictional characters Adrian Balboa and Paulie Pennino from the Rocky movies are located in the cemetery.[28] The Adrian Balboa tombstone was used as a prop in the 2006 motion picture Rocky Balboa and both were used in the 2015 motion picture Creed.[29] The two films show Rocky visiting the gravesite in the South Laurel Hill section of the cemetery. The tombstones were relocated to the current location near the main gatehouse.[25]

- In 2009, Laurel Hill was a movie location for the films Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen[30] and Law Abiding Citizen.[31]

- The 2009 young adult book Tombstone Tea[32] by Joanne Dahme takes place in Laurel Hill Cemetery and some of the well-known people buried there, such as Adam Forepaugh and Elisha Kent Kane, appear as characters.

Gallery

William J. Mullen was a prisoner's agent at Moyamensing Prison and had his monument built by Daniel Kornbau and exhibited at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition[24][33]

William J. Mullen was a prisoner's agent at Moyamensing Prison and had his monument built by Daniel Kornbau and exhibited at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition[24][33] Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler was the Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey and Standards of Weight and Measures

Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler was the Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey and Standards of Weight and Measures- The Mother and Twins Monument was carved by Polish sculpture Henry Dmochowski-Saunders. It depicts his deceased wife Helena Schaff and their two deceased children[34]

- The sculpture Aspiration by Harriet Whitney Frishmuth

Sculpture on William Warner memorial by Alexander Milne Calder depicting a woman releasing a soul from a sarcophagus[18]

Sculpture on William Warner memorial by Alexander Milne Calder depicting a woman releasing a soul from a sarcophagus[18] Levi Twiggs was a U.S. Marine Corps Officer who served during the War of 1812, the Seminole Wars and the Mexican-American War

Levi Twiggs was a U.S. Marine Corps Officer who served during the War of 1812, the Seminole Wars and the Mexican-American War- Sculpture on the Francis E. Patterson monument

Edwin Henry Fitler memorial

Edwin Henry Fitler memorial Memorial for Robert Patterson, Union General during the Civil War

Memorial for Robert Patterson, Union General during the Civil War Samuel Gibbs French was a Confederate Army Major General. He is buried in Florida but his family built this cenotaph to him in Laurel Hill.

Samuel Gibbs French was a Confederate Army Major General. He is buried in Florida but his family built this cenotaph to him in Laurel Hill. James Kitchenman memorial

James Kitchenman memorial

See also

- West Laurel Hill Cemetery

- List of United States cemeteries

Notes

- "General View of Laurel Hill Cemetery". The Library Company of Philadelphia. World Digital Library. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- "PHMC Historical Markers". Historical Marker Database. Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission. Archived from the original on December 7, 2013. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- National Historic Landmark Nomination, Aaron V. Wunsch, National Park Service, 1998.

- "NPGallery Digital Asset Management System". www.npgallery.nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- Listing Archived 2011-06-06 at the Wayback Machine at the National Park Service

- "Laurel Hill Cemetery". www.associationforpublicart.org. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- Tatman, Sandra L. "Smith, John Jay (1798 - 1881)". Philadelphia Architects and Buildings. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- Keels 2003, p. 21.

- Keels 2003, p. 22.

- Yaster 2017, p. 15.

- Keels 2003, p. 23.

- Smith 1852, pp. 39-44.

- Keels 2003, p. 27.

- Douglas, Ann, The Feminization of American Culture, 1977, New York, Alfred A. Knopf, pp. 208-213.

- Report of the Philadelphia Relief Committee. Philadelphia: Inquirer Printing Office. 1856. pp. 1–5. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- Yalom, Marilyn (2008). The American Resting Place: Four Hundred Years of History Through Our Cemeteries and Burial Grounds. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-618-62427-0.

- Keels 2003, p. 30.

- Keels 2003, p. 26.

- Keels 2003, p. 33.

- "The Silent Sentry will now stand watch in Laurel Hill Cemetery". www.civilwarcavalry.com. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ""Silent Sentry" historic Civil War memorial statue moved to Laurel Hill Cemetery". www.montgomerynews.com. The Review. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Yaster 2017, p. 8.

- Keels 2003, p. 31.

- Akintoye, Dotun. "Why does Rocky's wife get a tombstone at Laurel Hill?". www.mycitypaper.com. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- "Cleo - Laurel Hill Cemetery". www.waymarking.com. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- "David Rittenhouse". www.findagrave.com. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- Baskin, Ben. "Rocky Gets Right: How Creed (and Michael B. Jordan) Give the Boxing Franchise New Life". www.si.com. Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- "Creed (2015) Filming Locations". www.findagrave.com. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- "Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen". www.movie-locations.com. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- Elijah, Andy. "Philly Flix: Law Abiding Citizen". www.cinedelphia.com. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- Tombstone Tea Amazon listing Amazon.com. Retrieved 5 October 2009.

- Mullen Tomb December 26, 1881 article from the New York Times.

- Keels 2003, p. 32.

References

- Keels, Thomas H. (2003). Philadelphia Graveyards & Cemeteries. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-1229-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, R.A. (1852). Smith's Illustrated Guide to and through Laurel Hill Cemetery. Willis P. Hazard.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Warner, Ezra (1964). Generals in Blue: The Lives of the Union Commanders. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-0822-7. LCCN 64-21593.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yaster, Carol (2017). Laurel Hill Cemetery. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4671-2655-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Laurel Hill Cemetery. |

- Official website

- Historic American Buildings Survey, Laurel Hill Cemetery, HABS No. PA-1811 (Adobe .pdf format)

- Laurel Hill Cemetery at Find A Grave

- Laurel Hill Cemetery sculptures, Association for Public Art website

- From the collection of The Library Company of Philadelphia: