George Meade Easby

George Gordon Meade Easby (June 3, 1918 – December 11, 2005), also known as Meade or Mr. Easby, was a multi-talented person, from an artist to acting and producing films. He also served as an employee of the U.S. State Department for over twenty-five years and as a talk host on an AM radio station in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Easby was the great-grandson of General George Meade, victor of the 1863 Battle of Gettysburg against Robert E. Lee, and a descendant of seven signers of the U.S. Declaration of Independence.[1] Easby's mother was a descendant of Nicholas Waln, who came to Philadelphia in 1682 aboard the ship Welcome with William Penn, and was later given the section of the city now known as Frankford.[2][3]

George Meade Easby | |

|---|---|

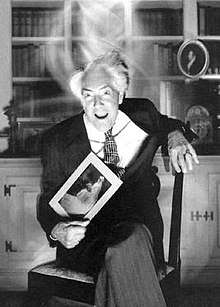

Mr. Easby appearing as a ghostly figure in a late October 1994 People magazine | |

| Born | June 3, 1918 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, US |

| Died | December 11, 2005 (aged 87) |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | Meade |

| Education | Chestnut Hill Academy |

| Alma mater | Philadelphia College of Art |

| Occupation | Actor, producer, radio host, artist, antique collector, author, political commentator |

| Years active | 1936–1982 |

Early life and family background

Easby was born on June 3, 1918 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His father was Major May Stevenson Easby, a banker in Philadelphia and World War I hero.[2] Easby's mother was Henrietta Meade Large Easby, described as "prim and reserved, a Victorian lady of few words".[4] He also had a younger brother Steven who died at a very young age in 1931 from some type of childhood disease.[5] The family "traces its roots to Easby Abbey in 12th Century Yorkshire, England; that crossed over to America in 1683 aboard the Welcome with William Penn, and that counts among its descendants three – "at least three that I know of," says Easby – signers of the Declaration of Independence."[6] General George Meade, victor of the 1863 Battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War, was Easby's great-grandfather through Meade's daughter. "My mother's mother was General (George G.) Meade's daughter," said Easby.[1][2]

Education and careers

Easby graduated from Chestnut Hill Academy in June 1936, after reaching the age of 18. To celebrate all of this, on July 9, 1936, his parents purchased for him a brand new convertible Packard Super Eight luxury automobile from the nearest Packard dealership (Goldner Brothers) on Germantown Avenue.[7] By the fall of the same year, he began studying illustration at the University of the Arts in Center City, Philadelphia.

After the start of World War II in 1939, Easby was drafted into the United States Army and was assigned to patrol (by air) the Atlantic Coast.[8] At the end of World War II Easby continued work as an artist and became a recognized cartoonist. He then got involved in acting and producing low-budget Hollywood films. Later, he worked as a radio talk host and as a U.S. State Department employee for over twenty-five years. He served on the Commission of Fine Arts and often met with highly important figures.

In the meantime, Easby became a major art and antique collector, who inherited more than 100,000 antiques and personal items, many of which had been in his family for centuries.[8] His collection includes items belonging to General George Meade, a chair and other high valued items belonging to Napoleon of France as well as jewelry belonging to Joséphine de Beauharnais. It also includes the very utensils that were used by the founding fathers of the United States during the signing of the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia. Many pieces from his collection have been loaned to the White House, U.S. State Department for its diplomatic reception rooms, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.[2] Some of his pieces are also housed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[9] Easby's furniture items were often traded at auctions such as Christie's and Sotheby's in the above one million dollar range each.[10][11][12] Among many of the antique watches and clocks left to Easby, one was made for the 18th-century Queen Marie Antoinette of France.[8]

Easby was also a collector of antique cars. He owned the 1954 Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith that was previously owned by Prince Aly Khan (husband of the famous American actress Rita Hayworth and father of Aga Khan IV),[13] his first vehicle (the Packard) and a few others.[2]

Following the January 1969 death of his father Easby has been living by himself in the family's Baleroy Mansion, which is located in the historically affluent Chestnut Hill section of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[14] It has been given a title as the "Most Haunted Home in America",[15] due to its infestation of spirits, ghosts, jinns, demons, angels or other supernatural beings that came to the 32-room mansion with the large collection of antiques. In 1990 Easby told The Philadelphia Inquirer, "The neighbors worry that it might become a Disney World with buses and tourists, but heavens, I've assured them that it won't."[6]

Death

Easby died on December 11, 2005, at a hospice (Keystone Hospice) in Wyndmoor, Pennsylvania. He was 87 years old at the time of his death and had no living siblings or children. The cause of his death was reported as "multiple organ failure".[8] According to a 2008 Philadelphia court record:

"... In September 2003, when Meade was released from Chestnut Hill Hospital, Dr. Moock (DR. Paul Moock, MD) prepared a discharge report that listed dementia as part of Meade's medical history. Several months later, Robert (Robert Paul Yrigoyen) asked Dr. Moock to write a letter describing Meade's condition and care requirements for tax purposes; Dr. Moock complied with a letter dated April 7, 2004, stating that he had been treating Meade for "dementia of the Alzheimer type" and because of this and other ailments "it is essential that Mr. Easby have full time nursing care." By April 2004, Dr. Moock testified that he was making house calls to care for Meade because of his refusal to get out of bed even though there was no physical reason preventing him from doing so. In December 2005, Meade was again admitted to Chestnut Hill Hospital. It was determined that he had terminal lung disease and he was given hospice care until he died 3 days later. ...[16]

Easby was buried at Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia. He was known as an extremely kind and generous person.[17]

Further reading

- Nesbitt, Mark and Wilson, Patty A. 2006. "Haunted Pennsylvania: Ghosts and Strange Phenomena of the Keystone State". Stackpole Books, 2006. ISBN 0-81173-298-3.

References

- "Spirited Welcome". People. October 31, 1994. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

Guests at George Easby's Historic Philadelphia Mansion Discover They May Not Be Alone

- Avery, Ron (July 26, 1991). "'Squire' Revels in Domain Baleroy's Items Are Lent To White House And Museums". Philadelphia Media Network. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

- Lear, Len (December 15, 2005). "Visitors didn't stand a "ghost of a chance" George G. Meade Easby, a one-of-a-kind Hiller". Chestnut Hill Local. Archived from the original on August 12, 2010. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

- The Baleroy Mansion

- "May Stevenson Easby, Jr". Retrieved December 17, 2013.

- Ginny Wiegand (December 3, 1990). "A Haunting Tale Of Blue Blood And Red Tape". Philadelphia Media Network. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

- "1935 Packard Super Eight Convertible Sedan (Engine no. 755611 – Vehicle no. 883-209)". Retrieved December 17, 2013.

this Packard Super Eight, which the 18-year-old Easby purchased new on July 9, 1936, from Goldner Brothers, of Germantown, Pennsylvania. In many ways, the convertible sedan represented the ultimate eight-cylinder offering from East Grand Boulevard that year. Built on the 1205 chassis, it stretched 144 inches from axle to axle and was powered by a 150-horsepower, silky-smooth L-head straight eight, sending its power through an all-synchromesh transmission. Befitting a formal car, Easby's Packard was finished in a stately all-over black with green button-tufted leather upholstery and canvas top; only the door saddles were painted cream.

- Ronan Sims, Gayle (December 14, 2005). "George Gordon Meade Easby, 87". Philadelphia Media Network. Retrieved December 17, 2013.

- Lear, Len (December 15, 2005). "Obituaries (George Easby)". Chestnut Hill Local. Archived from the original on December 13, 2009. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

- Solis-Cohen, Lita (January 22, 1990). "A 1776 Phila. Table Sets Auction Record Of $4.62 Million". Philadelphia Media Network. Retrieved December 17, 2013.

- "A Cool Hand and a Keno Eye". New York Magazine. Retrieved December 17, 2013.

- Moonan, Wendy (January 11, 2008). "Americana Dealer Cleans House". The New York Times. Retrieved December 17, 2013.

- "1954 Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith (1954 Short Wheelbase Style 7249 Tourer – LWVH114)". classicdriver.com. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

The automobile reportedly then passed to the Ali Kahn, husband of Rita Hayworth, on its way to its very long term owner, George Gordon Meade Easby.

- "Chestnut Hill's Baleroy Mansion's Many Ghost Stories". chestnuthill.patch.com. October 31, 2011. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

- Coulombe, Charles A. (2004). Haunted Places in America: A Guide to Spooked and Spooky Public Places in the United States. Globe Pequot. p. 184. ISBN 1-5992-1706-6. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

- "Estate of George Gordon Meade Easby, Deceased" (PDF). Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia. 2008. p. 17. Retrieved December 21, 2013.

- "Baleroy Mansion – Chestnut Hill, PA". Archived from the original on September 11, 2013. Retrieved September 5, 2007.