King's Cross Thameslink railway station

King's Cross Thameslink station is a closed railway station in central London, England. It is located on Pentonville Road, around 250 metres (0.2 mi) east of King's Cross mainline station. At the time of closure, in 2007, it was on the Thameslink route between Farringdon and Kentish Town stations and managed by First Capital Connect.

| King's Cross Thameslink | |

|---|---|

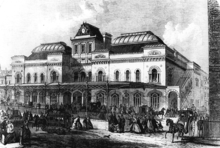

King's Cross Thameslink before its closure | |

| Location | |

| Place | Kings Cross |

| Area | London Borough of Camden |

| Coordinates | 51.5308°N 0.1202°W |

| Grid reference | TQ303830 |

| Operations | |

| Original company | Metropolitan Railway |

| Pre-grouping | Metropolitan Railway |

| Post-grouping | Metropolitan Railway |

| Platforms | 2 at closure (originally 4) |

| Annual rail passenger usage | |

| 2004/05 * | |

| 2005/06 * | |

| 2006/07 * | |

| 2007/08 * | |

| History | |

| 1863 | Opened as King's Cross Metropolitan |

| 1940 | London Underground platforms closed |

| 1979 | Closed as part of the Great Northern Electrification Project |

| 1983 | Reopened as King's Cross Midland City |

| 1988 | Renamed to King's Cross Thameslink |

| 2007 | Closed permanently |

| Disused railway stations in the United Kingdom | |

| * Annual passenger usage based on sales of tickets in stated financial year(s) which end or originate at King's Cross Thameslink from Office of Rail Regulation statistics. Please note: methodology may vary year on year. | |

| Closed railway stations in Britain A B C D–F G H–J K–L M–O P–R S T–V W–Z | |

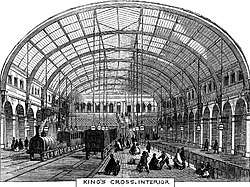

The station opened in 1863 as King's Cross Metropolitan. It was one of the initial seven stations on the Metropolitan Railway, London's first underground line, which ran between Paddington and Farringdon. The Metropolitan had been planning for the station since 1851, when King's Cross mainline station was constructed, to provide a connection between the Great Western Railway at Paddington and the Great Northern Railway (GNR) out of King's Cross. Within a year of opening a pair of tunnels was added, which surfaced on the GNR just north of King's Cross and provided a direct rail connection between the two lines. In 1866 the line was extended east to Moorgate and south through Snow Hill tunnel to join the London, Chatham and Dover Railway at Ludgate Hill, and in 1868 a second pair of tracks known as the City Widened Lines was opened along with a tunnel connection to the Midland Railway near St Pancras station. The route through the station was very busy throughout the remainder of the century, carrying trains from five companies. In 1892 the station was linked to the concourse of King's Cross mainline station by a foot tunnel.

The opening of the Piccadilly and Northern underground lines, as well as the growth of trams on the surface streets, led to a sharp reduction of services on the City Widened Lines in the early twentieth century. The Metropolitan line remained popular, however, following electrification of its tracks in 1905–06. Passenger service was reduced to peak hours only during World War I, with no service through the Snow Hill tunnel, as the lines were used heavily for freight and troop movements. The line and station were closed for five months during World War II, following damage in The Blitz. Only the City Widened Lines platforms remained in use when the station reopened in 1941: the Metropolitan line station was moved to a new pair of platforms which had been built at King's Cross St Pancras tube station, providing a shorter connection to the Piccadilly and Northern lines. Trains from the East Coast main line and Midland main line continued to stop at King's Cross Metropolitan. In the 1980s the City Widened Lines were electrified and the Snow Hill tunnel reopened to passenger traffic as part of the Thameslink programme. The station was renamed, first to King's Cross Midland City and then to its final name, King's Cross Thameslink. Service on the line grew and new destinations were added, and by the 2000s the station could no longer handle the passenger numbers. A new pair of platforms were built at St Pancras, and King's Cross Thameslink closed in 2007. The station was included in the London station group from the group's inception in 1983, and remained so until its closure.

Naming

The station was officially known as King's Cross Metropolitan when it opened by the Metropolitan Railway in 1863,[1] although on timetables and maps it was often just called King's Cross or King's Cross (Met.).[2] The Metropolitan line part of the station was renamed to King's Cross & St Pancras in 1925 and then to King's Cross St Pancras in 1933,[3] when the Metropolitan Railway was merged with the Underground Electric Railways Company of London to form the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB).[4] The station was then part of the King's Cross St Pancras tube station complex. The City Widened Lines platforms continued to be signed as King's Cross through to the 1970s.[5] When the station reopened in 1983, following electrification, it was known as King's Cross Midland City and acquired its final name, King's Cross Thameslink, in 1988.[1]

Location and layout

King's Cross Thameslink is located in a cutting around 250 metres (0.2 mi) east of King's Cross mainline station.[6][1] The station's main entrance was on the north side of the station at the western end of Pentonville Road,[7] part of the London Inner Ring Road. This replaced an earlier entrance located south of the tracks on Gray's Inn Road.[1] The Thameslink platforms were linked directly by stairs and a tunnel to the Victoria and Piccadilly line platforms at King's Cross St Pancras, and via both sets of platforms to the Circle, Hammersmith & City, Metropolitan and Northern lines as well as the mainline stations at King's Cross and St Pancras.[8]

The station had four platforms. The two to the south were for the Metropolitan line, and were used from 1863 to 1940. The two northern platforms, used from 1863 to 1979 and from 1983 to 2007, served the City Widened Lines and later the Thameslink service. The southbound Metropolitan and northbound Widened shared an island platform. After closure of the Metropolitan platforms a high wall was built on that island.[1] The two platforms in use during the King's Cross Thameslink era were lettered rather than numbered,[9] to avoid confusion with the platforms at nearby King's Cross among staff who worked at both stations.[10]

In 1983, British Rail introduced the London station group, a group of stations in central London which were regarded as a single destination for ticketing and fare purposes. King's Cross Midland City, as it was then called, was one of the original eighteen stations in the group,[11] and it retained this status until closure in 2007.[12]

History

Early history

The area of King's Cross was previously a village known as Battle Bridge, an ancient crossing of the River Fleet. The river flowed along what is now the west side of Pancras Road until it was rerouted underground in 1825.[13] The mainline King's Cross station was built in 1851–52 as the London terminus of the Great Northern Railway (GNR), and was the fifth London terminal to be constructed.[14] The station took its name from the King's Cross building, a monument to King George IV that stood in the area and was demolished in 1845.[15] Plans for the station were made in December 1848 under the direction of George Turnbull, resident engineer for constructing the first 20 miles (32 km) of the Great Northern Railway out of London.[16][17] The station opened on 14 October 1852.[14] The first suburban services to and from King's Cross began operating in 1861, initially to Seven Sisters Road station (which was renamed to Finsbury Park in 1869), and later to Hornsey and beyond.[18]

King's Cross Metropolitan

The first underground station at King's Cross was planned in 1851, during construction of the mainline station. The intention was to connect the Great Western Railway (GWR) at Paddington with the Great Northern Railway (GNR) at King's Cross.[19][20] The line was opened on 10 January 1863, along with six other stations,[3] as part of the original section of the Metropolitan Railway, which would later become part of the London Underground.[21] King's Cross Metropolitan, the predecessor of King's Cross Thameslink, opened at the same time and was located to the east of the mainline station.[22] The line was initially dual gauge, enabling both the GWR's broad gauge trains and other standard gauge stock to run.[23] Later that year a pair of tunnels—the York Road Curve for southbound trains and the Hotel Curve for northbound trains—were built, joining the GNR lines north of King's Cross mainline with the Metropolitan's line at King's Cross Metropolitan.[24] The GWR ran the first trains on the line, but relations towards the Metropolitan quickly became strained and the GWR withdrew from the route in August 1863. The Metropolitan was able to continue operating by leasing rolling stock from the GNR, which it brought on to the line through the York Road tunnel.[23] The GNR started routing all its suburban trains through the tunnels to Farringdon Street (now Farringdon) station in October. Trains into London stopped at a new platform known as King's Cross York Road to the north east of the mainline station, and again at the Metropolitan station, while trains out of London stopped at the Metropolitan station, and again at the mainline station, by reversing into a platform after exiting the Hotel Curve.[22]

In 1866 the Snow Hill tunnel was opened, joining the Metropolitan Railway at Farringdon Street to the London, Chatham and Dover Railway (LCDR) terminus at Ludgate Hill.[22] This allowed goods and passenger trains to run from the GNR lines south through to Herne Hill and beyond.[22] The lines became very congested, leading to the opening in 1868 of a new pair of lines known as the City Widened Lines. These ran alongside the original tracks from King's Cross through to Moorgate,[25] and allowed GNR and Metropolitan traffic to run along the line simultaneously.[26] The same year the Metropolitan built a pair of tunnels to the Midland Railway tracks north of its new terminus at St Pancras station.[27] This enabled the Midland to begin running a service from Bedford through to Moorgate.[24] The Midland tunnels as well as the original York Road and Hotel Curve tunnels from King's Cross mainline station were connected to the City Widened Lines, while the link to the original Metropolitan lines was removed.[28] The original Metropolitan tracks became part of the Inner Circle (later known as the Circle line), which ran partly on Metropolitan tracks and partly on District Railway tracks. The line was completed in 1884.[29] Services were provided by both the Metropolitan, which ran the clockwise trains and the District, which ran anticlockwise.[30]

The route through King's Cross Metropolitan remained busy throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century, with trains from five companies—the Metropolitan, GNR, Midland, LCDR and the South Eastern Railway (SER)—and routes including Victoria to Peterborough as well as services from north London to Chatham and Dover.[31] A service operated from Liverpool to Paris via the Widened Lines, departing at 08:00 and arriving in Paris by 22:50, having travelled by across the English Channel in a paddle steamer.[32] Trains continued to ascend up the Hotel Curve from the Metropolitan station and reverse into the mainline station until 1878, when a new platform was built on the western side of the GNR tracks. This became known as the King's Cross Suburban station, but suffered from several problems including a steep incline and sharp curve, along with a build-up of smoke because of its proximity to the mouth of the tunnel.[33] Congestion was somewhat alleviated when a connection between Finsbury Park and Canonbury allowed use of the North London Railway tracks to take some of the traffic from the GNR lines into Broad Street station in the City of London rather than down the Metropolitan line.[34] In 1892 the station was linked to the concourse of the mainline station by a foot tunnel.[35]

Arrival of the deep tube and relocation of Metropolitan platforms

The advent of deep-level tube lines at the turn of the twentieth century caused major changes in the underground network. The Great Northern, Piccadilly & Brompton Railway, later known as the Piccadilly line, opened a station serving King's Cross and St Pancras in 1906, and the City & South London Railway, now part of the Northern line, opened its station the following year.[36] The tube platforms were linked to King's Cross Metropolitan through the same foot tunnel as the mainline, making one station complex.[35] The Metropolitan line part of the station was amalgamated in 1933 with the deep-level lines as part of the newly-formed the LPTB.[4] The arrival of the Piccadilly and Northern lines, as well as the growth of trams on the surface streets, led to a sharp reduction of services on the City Widened Lines.[24] The SER, LCDR, and GNR services were withdrawn in 1907, and the Midland and LC&DR joint service in June the following year.[37] The decreased passenger service allowed a growth in freight traffic through the station. During World War I the line was used for freight and troop movements with 250,000 tons of freight and 26,047 special troop trains passing through. Passenger service was reduced to four hours per day during morning and evening peak hours from 1915.[24] The Snow Hill tunnel closed to passenger service during the war, and the north–south link was used only by freight in the postwar years.[38] Service on the Circle and Metropolitan line tracks increased over subsequent years, however, following electrification of those tracks in 1905–06.[39]

The infrastructure around King's Cross was bombed by Germany in 1940 during the Blitz early in World War II. The Circle line between Euston Square and King's Cross was particularly damaged and services stopped completely for five months.[40] When the line reopened in March 1941 a new pair of platforms were opened to the west, making use of abandoned tunnels from the 1860s and providing a shorter connection to the Piccadilly and Northern lines.[24] This scheme, part of what is now Kings Cross St Pancras tube station, had been planned by the MR since 1935.[10] The original platforms were abandoned but are still in place and visible from passing trains as of 2019.[24] After the war, national rail services continued to use the City Widened Lines platforms of the original station from the GNR route (now known as the East Coast Mainline) and from the Midland Mainline.[24]

Thameslink programme

The Snow Hill tunnel, which had seen no passenger services since 1916, closed completely on 24 March 1969 with the withdrawal of freight services; the tracks were lifted in May 1971.[41] Services from the East Coast line then ended in 1976 after the Northern City Line was transferred from London Underground control to British Rail, allowing services to run from Finsbury Park directly to Moorgate avoiding King's Cross.[42] A handful of services from the Midland line continued to run, but the Widened Lines were almost unused in the late 1970s.[42]

In 1979 an £80 million project was launched to electrify the Midland Mainline from Bedford to St Pancras and the City Widened Lines.[42] The station was closed, along with the line, and work was completed by May 1982. The tracks were lowered to allow for overhead power cables to be installed and several bridges were remodelled. Despite completion of the line and availability of rolling stock by early 1983, the opening of the line was delayed over a dispute with the Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen (ASLEF) union regarding driver-only operation on the new electric trains.[43] The station eventually reopened later in 1983, with the new name of King's Cross Midland City. Trains ran between Bedford and Moorgate, via St Pancras and the tunnels from the Midland mainline to the City Widened Lines.[44]

In 1988 Network SouthEast, one of the newly created sectors of the state-owned British Rail,[45] implemented a scheme first proposed in the 1960s to reopen the Snow Hill tunnel to passenger traffic.[38] The project, and the new north–south connection created, was called Thameslink. Trains ran between Bedford and Brighton using Class 319 dual-voltage trains which could run on both the Midland Mainline's overhead AC system and the Brighton Mainline's third-rail system.[45] Five years after its previous rename, the station at King's Cross was once again renamed, this time to King's Cross Thameslink.[24] Services on the line grew and new stations were added, including a station at the southern end of the Snow Hill tunnel named City Thameslink, which replaced the earlier terminal Holborn Viaduct station which was not on the through route.[46]

At around the time Thameslink was launched, British Rail began active planning for the Channel Tunnel Rail Link, a new high-speed line to link London with the Channel tunnel. The initial proposal was for the line to end at a new "King's Cross Low Level" station, which would run from north west to south east underneath the Great Northern Hotel and the mainline terminal, and would become a joint station for Eurostar and Thameslink services.[47] This plan was developed in some detail by architect Norman Foster, but was ultimately vetoed by the government in 1990 due to high costs.[48] The project, which became known as High Speed 1, was eventually completed in 2007 with terminal platforms at St Pancras rather than King's Cross.[49]

Closure and relocation

In the mid-2000s, Network Rail began work on the Thameslink Programme, a scheme originally proposed in around 1990 but delayed several times.[50][51] The plan involved increasing the service frequency between King's Cross and Blackfriars up to 24 trains per hour.[50] Planners for the programme decided that the existing King's Cross Thameslink station would be unable to cope with this increase. They criticised its substandard platform widths and lengths, lack of step-free access and fire escape routes, as well as the poor-quality passenger environment.[52] They decided to move the station rather than upgrade it at its existing location. The surrounding infrastructure made this impractical and it would also have caused serious disruption to the Circle, Hammersmith & City and Metropolitan Underground lines as well as nearby roads.[52] The siting of the High Speed 1 terminus under St Pancras rather than King's Cross also meant that the Thameslink platforms were a long distance by foot from the planned Eurostar platforms.[53]

Network Rail initially considered reusing the abandoned Norman Foster proposal, which had called for a combined Eurostar and Thameslink station underneath King's Cross mainline station, but updated to be for Thameslink only. This would have the advantage of fewer closures to the line during construction, as the site was not on the existing line. Ultimately though, due to the cost of relocating the lines and the political issues with demolishing the Grade-II-listed Great Northern Hotel, Network Rail decided to build the new platforms on the existing alignment, under the St Pancras complex.[48] The new platforms are close to the High Speed 1 platforms used by Eurostar trains, and provide an easier connection to the mainline stations at St Pancras and King's Cross.[54] The work required closure of the through Thameslink line for eight months in 2004–05, with trains from the north terminating at St Pancras.[53][55] The project then stalled but was rescued by extra funding of £63 million in February 2006.[55] The last train at King's Cross Thameslink was the 23:59 from Haywards Heath, which called at the station at 01:08 on Sunday 9 December 2007.[56] From 9 December 2007, Thameslink services started to call at the new platforms at St Pancras.[57]

The foot tunnel from King's Cross St Pancras tube station to the ticket office of the former Thameslink station remains open from 07:00 to 20:00 on Mondays to Fridays, to provide extra access to London Underground platforms from Pentonville Road.[58]

Services

The off-peak service pattern for King's Cross Thameslink in 2007, the year of its closure, was as follows:[59]

- 4 tph to Brighton via London Bridge and Gatwick Airport

- 4 tph to Sutton, 2 tph via Wimbledon and 2 tph via Mitcham Junction.

- 4 tph to Bedford via St Albans City, Luton Airport and Luton.

- 2 tph to Luton via St Pancras International, St Albans City and Luton Airport

- 2 tph to St Albans City via Hendon

| Preceding station | Historical railways | Following station | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Kentish Town Line and station open | First Capital Connect Thameslink | Farringdon Line and station open |

||

| London King's Cross York Road (southbound) Suburban (northbound) Lines closed, station open |

Great Northern Railway City Widened Lines |

|||

| London, Chatham & Dover Railway City branch |

||||

| Camden Road Line open, station closed |

Midland Railway | |||

| Preceding station | Following station | |||

| Euston Square | Metropolitan Railway 1863–1933 |

Farringdon | ||

| Metropolitan line 1933–1940 |

||||

Notes

- Pedroche 2011, pp. 30–31.

- Thomas 1971, p. 228.

- Rose 2016.

- Saxton 2015, p. 78.

- Nick Catford. "Kings Cross Station in May 1976". Disused Stations. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- "King's Cross Station, Euston Road, London to Kings Cross Caledonian Road (Stop X)" (Map). Google Maps. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "Station Facilities: King's Cross Thameslink". National Rail. Archived from the original on 8 April 2008. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "King's Cross St Pancras platform diagram" (Map). London Underground. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "Electric Railway". 49–50. Doppler Press. 2004: 20. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Nick Catford. "King's Cross Thameslink". Disused Stations. Archived from the original on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "1.5: Routeing of Tickets". Selective Prices Manual Number 27. London: British Railways Board. 22 May 1983. p. A3.

- NFM 97. National Fares Manuals. London: Association of Train Operating Companies (ATOC Ltd). May 2007. Section A.

- Godfrey, Walter H; Marcham, W McB., eds. (1952). Battle Bridge Estate. Survey of London. 24, the Parish of St Pancras Part 4: King's Cross Neighbourhood. London. pp. 102–113. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- Weinreb et al. 2010, p. 463.

- Thornbury, Walter (1878). "Highbury, Upper Holloway and King's Cross". Old and New London. London. 2: 273–279. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- Diaries of George Turnbull (Chief Engineer, East Indian Railway Company) held at the Centre of South Asian Studies at Cambridge University, England.

- Page 87 of George Turnbull, C.E. 437-page memoirs published privately 1893, scanned copy held in the British Library, London on compact disk since 2007.

- Nock 1974, pp. 63–64.

- Day & Reed 2010, p. 9.

- Wolmar 2012, p. 30.

- Day & Reed 2010, p. 14.

- Jackson 1984, p. 70.

- Thomas 1971, pp. 82–83.

- Phil Haigh (19 October 2018). "Widening the horizons..." Rail Magazine. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- Jackson 1984, p. 71.

- Day & Reed 2010, pp. 16–17.

- Wolmar 2012, p. 62.

- Nock 1974, p. 70.

- Simpson, Bill (2003). A History of the Metropolitan Railway. Volume 1: The Circle and Extended Lines to Rickmansworth. Lamplight Publications. pp. 23–24. ISBN 1-899246-07-X.

- Bruce 1983, p. 11.

- Nock 1974, pp. 72–73.

- Martin 2013, p. 56.

- Jackson 1984, p. 72.

- Jackson 1984, p. 73.

- Jackson 1984, p. 78.

- Day & Reed 2010, p. 47.

- Jackson 1986, p. 50.

- Russell Haywood (2016). Railways, Urban Development and Town Planning in Britain: 1948–2008. Routledge. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- Thomas 1971, pp. 93–94.

- London Passenger Transport Board (1945). Twelfth annual report and statement of accounts. p. 14.

- Brown 2015, p. 32.

- Day 1979, p. 153.

- Trevor Skeet (21 February 1983). "Bedford-St. Pancras Railway Line (Electrification)". House of Commons adjournment debate. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- John Christopher (2012). Kings Cross Station Through Time. Amberley Publishing Limited. p. 171. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- Rail Magazine (3 June 2017). "Thameslink's road to fruition".

- Simmons & Biddle 1997, p. 506.

- Schabas 2017, p. 145.

- Schabas 2017, p. 146.

- Schabas 2017, p. 160.

- "Rail masterplan at a glance". BBC News. 14 January 2002. Archived from the original on 23 May 2006. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- Laurence Knight (20 February 2011). "London's overlooked rail project". BBC News. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- "Thameslink 2000 Closures Statement of Reasons" (PDF). Network Rail. 4 November 2005. p. 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2006. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- Schabas 2017, p. 155.

- Schabas 2017, p. 156.

- "Thameslink station given go-ahead". BBC News. 8 February 2006. Archived from the original on 24 December 2007. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- "St Pancras International". First Capital Connect. Archived from the original on 17 May 2007.

- Clark, Emma (10 December 2007). "New station sets the standard". Watford Observer. Archived from the original on 24 February 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- Tim Dunn (16 December 2016). "The hidden tunnels beneath King's Cross station". London Transport Museum. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- "Train Times: 10 December 2006 – 19 May 2007" (PDF). First Capital Connect. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 January 2007. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

References

- Brown, Joe (2015) [2006]. London Railway Atlas (4th ed.). Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-3819-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bruce, J Graeme (1983). Steam to Silver. A history of London Transport Surface Rolling Stock. Capital Transport. ISBN 0-904711-45-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Day, John R (1979) [1963]. The Story of London's Underground. London Transport Executive. ISBN 0853290946.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Day, John R; Reed, John (2010) [1963]. The Story of London's Underground (11th ed.). Capital Transport. ISBN 9781854143419.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jackson, Alan (1984) [1969]. London's Termini. David & Charles. ISBN 0330027476.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jackson, Alan (1986). London's Metropolitan Railway. David & Charles. ISBN 0715388398.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martin, Andrew (2013). Underground Overground: A Passenger's History of the Tube. London: Profile Books. ISBN 978-1-846-68478-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nock, Oswald Stevens (1974) [1958]. The Great Northern Railway. ISBN 9780711004948.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pedroche, Ben (2011). Do Not Alight Here: Walking London's lost underground and railway stations. Capital History. ISBN 9781854143525.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rose, Douglas (2016) [1980]. The London Underground : A Diagrammatic History (Map) (9th ed.). Capital Transport Publishing. ISBN 9781854144041.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Saxton, Peter (2015). Making Tracks: A Whistle-stop Tour of Railway History. Michael O'Mara Books. p. 78.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schabas, Michael (2017). The Railway Metropolis: how planners, politicians and developers shaped modern London. ICE Publishing. ISBN 9780727761804.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simmons, Jack; Biddle, Gordon (1997). The Oxford companion to British railway history: from 1603 to the 1990s. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192116975.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thomas, David St. John (1971). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Greater London. David and Charles. ISBN 9780715353370.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weinreb, Ben; Hibbert, Christopher; Keay, Julia; Keay, John (2010). The London Encyclopedia. Pan MacMillan. ISBN 9781405049245.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wolmar, Christian (2012) [2004]. The Subterranean Railway. Atlantic Books. ISBN 9780857890696.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to King's Cross Thameslink railway station. |

- "Kings Cross Thameslink". Disused Stations. Subbrit. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014.

- "Kings Cross Thameslink". London's Abandoned Stations. Archived from the original on 28 September 2008.

- "First Capital Connect website". First Capital Connect. Archived from the original on 30 December 2005.