Khafra

Khafra (also read as Khafre, Khefren and Greek: Χεφρήν Chephren) was an ancient Egyptian king (pharaoh) of the 4th Dynasty during the Old Kingdom. He was the son of Khufu and the throne successor of Djedefre. According to the ancient historian Manetho, Khafra was followed by king Bikheris, but according to archaeological evidence he was instead followed by king Menkaure. Khafra was the builder of the second largest pyramid of Giza. The view held by modern Egyptology at large continues to be that the Great Sphinx was built in approximately 2500 BC for Khafra.[2] Not much is known about Khafra, except from the historical reports of Herodotus, writing 2,000 years after his life, who describes him as a cruel and heretical ruler who kept the Egyptian temples closed after Khufu had sealed them.

| Khafra | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khafre, Khefren, Suphis II., Saophis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

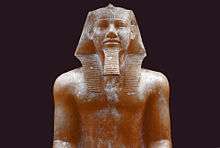

Alabaster statue of Khafra, probably from Memphis, now in the Egyptian Museum at Cairo. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | About 26 years, ca. 2570 BC[1] (4th Dynasty) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Djedefre | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Bikheris (?), Menkaure | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Meresankh III, Khamerernebty I, Persenet, Hekenuhedjet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Nebemakhet, Duaenre, Niuserre, Khentetka, Shepsetkau, Menkaure, Khamerernebty II, Sekhemkare, Nikaure, Ankhmare, Akhre, Iunmin, Iunre, Rekhetre, and Hemetre | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Khufu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Meritites I or Henutsen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Pyramid of Khafra | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monuments | Pyramid of Khafra | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Family

Khafra was a son of king Khufu and the brother and successor of Djedefre.[3] Khafra is thought by some to be the son of Queen Meritites I due to an inscription where he is said to honor her memory.

Kings-wife, his beloved, devoted to Horus, Mertitytes.

King's-wife, his beloved, Mertitytes; beloved of the Favorite of

the Two Goddesses; she who says anything whatsoever and it is done

for her. Great in the favor of Snefr[u] ; great in the favor

of Khuf[u], devoted to Horus, honored under Khafre. Merti[tyt]es.[Breasted; Ancient Records]

Others argue that the inscription just suggests that this queen died during the reign of Khafre.[4] Khafre may be a son of Queen Henutsen instead.[5]

Khafra had several wives and he had at least 12 sons and 3 or 4 daughters.

- Queen Meresankh III was the daughter of Kawab and Hetepheres II and thus a niece of Khafra. She was the mother of Khafra's sons Nebemakhet, Duaenre, Niuserre and Khentetka, and a daughter named Shepsetkau.

- Queen Khamerernebty I was the mother of Menkaure and his principal queen Khamerernebty II.

- Hekenuhedjet was a wife of Khafra. She is mentioned in the tomb of her son Sekhemkare.

- Persenet may have been a wife of Khafra based on the location of her tomb. She was the mother of Nikaure.[3]

Other children of Khafra are known, but no mothers have been identified. Further sons include Ankhmare, Akhre, Iunmin, and Iunre. Two more daughters named Rekhetre and Hemetre are known as well.[3]

Reign

There is no agreement on the date of his reign. Some authors say it was between 2558 BC and 2532 BC. While the Turin King List length for his reign is blank, and Manetho exaggerates his reign as 66 years, most scholars believe it was between 24 and 26 years, based upon the date of the Will of Prince Nekure which was carved on the walls of this Prince's mastaba tomb. The will is dated anonymously to the Year of the 12th Count and is assumed to belong to Khufu since Nekure was his son. Khafra's highest year date is the "Year of the 13th occurrence" which is a painted date on the back of a casing stone belonging to mastaba G 7650.[6] This would imply a reign of 24–25 years for this king if the cattle count was biannual during the Fourth Dynasty.

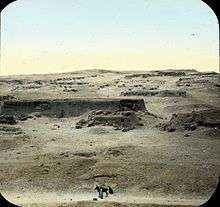

Pyramid complex

Khafra built the second largest pyramid at Giza. The Egyptian name of the pyramid was Wer(en)-Khafre which means "Khafre is Great".[7]

The pyramid has a subsidiary pyramid, labeled GII a. It is not clear who was buried there. Sealings have been found of a King's eldest son of his body etc. and the Horus name of Khafre.[7]

Valley Temple

The valley temple of Khafre was located closer to the Nile and would have stood right next to the Sphinx temple. Inscriptions from the entrance way have been found which mention Hathor and Bubastis. Blocks have been found showing the partial remains of an inscription with the Horus name of Khafre (Weser-ib). Mariette discovered statues of Khafre in 1860. Several were found in a well in the floor and were headless. But other complete statues were found as well.[7]

Mortuary Temple

The mortuary temple was located very close to the pyramid. From the mortuary temple come fragments of maceheads inscribed with Khafre's name as well as some stone vessels.[7]

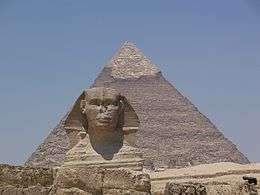

Great Sphinx and Sphinx temple

The sphinx is said to date to the time of Khafra. This is supported by the proximity of the sphinx to Khafra's pyramid temple complex, and a certain resemblance (despite damage) to the facial structure seen in his statues. The Great Sphinx of Giza may have been carved out as a guardian of Khafra's pyramid, and as a symbol of royal power. It became deified during the time of the New Kingdom.[8]

Khafra in ancient Greek traditions

The ancient Egyptian historian Manetho called Khafra “Sûphis II.” and credited him with a rulership of 66 years, but didn't make any further comments about him.[9][10][11][12]

The ancient Greek historians Diodorus and Herodotus instead depicted Khafra as a heretic and cruel tyrant: They were writing 2,000 years after his time that Khafra (whom they both called “Khêphren”) followed his father Khêops on the throne, after the megalomaniac despot had died. Then Herodotus and Diodorus say that Khafra ruled for 56 years and that the Egyptians had to suffer under him like under his father before. Since Khufu was said to have ruled for 50 years, the authors claim that the poor Egyptians had to suffer under both kings for altogether 106 years.[9][10][11]

But then they describe a king Menkaura (whom they call “Mykerînós”) as the follower of Khafra and that this king was the counterpart of his two predecessors: Herodotus describes Menkaura as being saddened and disappointed about Khufu's and Khafra's cruelty and that Menkaura brought peace and piety back to Egypt.[9][10][11]

Modern Egyptologists evaluate Herodotus's and Diodorus's stories as some sort of defamation, based on both authors' contemporary philosophy. Oversized tombs such as the Giza pyramids must have appalled the Greeks, and even the later priests of the New Kingdom because they surely remembered the heretic pharaoh Akhenaten and his megalomaniacal building projects. This extremely negative picture was obviously projected onto Khafra and his daunting pyramid. This view was possibly promoted by the fact that during Khafra's lifetime the authority to give permission for the creation of oversized statues made of precious stone and for their display in open places in public was restricted to the king only. In their eras, the Greek authors and mortuary priests and temple priests couldn't explain the impressive monuments and statues of Khafra as anything other than the result of a megalomaniacal character. These views and resulting stories were avidly snapped up by the Greek historians and so they made their also negative evaluations about Khafra, since scandalous stories were easier to sell to the public than positive (and therefore boring) tales.[9][10][11][12]

References

- Thomas Schneider: Lexikon der Pharaonen. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3, page 102.

- "Sphinx Project: Why Sequence is Important". 2007. Archived from the original on July 26, 2010. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- Dodson, Aidan and Hilton, Dyan. The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. 2004. ISBN 0-500-05128-3

- Grajetzki, Ancient Egyptian Queens: A Hieroglyphic Dictionary, Golden House Publications, London, 2005, ISBN 978-0-9547218-9-3

- Tyldesley, Joyce. Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt. Thames & Hudson. 2006. ISBN 0-500-05145-3

- Anthony Spalinger, Dated Texts of the Old Kingdom, SAK 21 (1994), p.287

- Porter, Bertha and Moss, Rosalind, Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Reliefs and Paintings Volume III: Memphis, Part I Abu Rawash to Abusir. 2nd edition (revised and augmented by Dr Jaromir Malek, 1974. Retrieved from gizapyramids.org Archived 2008-10-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Markowitz, Haynes, Freed (2002). Egypt in the Age of the Pyramids.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Siegfried Morenz: Traditionen um Cheops. In: Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde, vol. 97, Berlin 1971, ISSN 0044-216X, page 111–118.

- Dietrich Wildung: Die Rolle ägyptischer Könige im Bewußtsein ihrer Nachwelt. Band 1: Posthume Quellen über die Könige der ersten vier Dynastien (= Münchener Ägyptologische Studien. Bd. 17). Hessling, Berlin 1969, page 152–192.

- Wolfgang Helck: Geschichte des Alten Ägypten (= Handbuch der Orientalistik, vol. 1.; Chapter 1: Der Nahe und der Mittlere Osten, vol 1.). BRILL, Leiden 1968, ISBN 9004064974, page 23–25 & 54–62.

- Aidan Dodson: Monarchs of the Nile. American Univ in Cairo Press, 2000, ISBN 9774246004, page 29–34.

Further reading

- James H. Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, Part I, §§ 192, (1906) on 'The Will of Nekure'.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Khafra. |