Osorkon II

Usermaatre Setepenamun Osorkon II was the fifth king[1] of the Twenty-second Dynasty of Ancient Egypt and the son of King Takelot I and Queen Kapes. He ruled Egypt from approximately 872 BC to 837 BC from Tanis, the capital of that dynasty.

| Osorkon II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Pendant bearing the cartouche of Osorkon II seated King Osorkon flanked by Horus and Isis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 872–837 BC (22nd Dynasty) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Takelot I | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Shoshenq III | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Karomama I | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Tjesbastperu, Nimlot C, Shoshenq D, Hornakht | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 837 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | NRT-I Tanis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

After succeeding his father, Osorkon II was faced with the competing rule of his cousin, King Harsiese A, who controlled both Thebes and the Western Oasis of Egypt. Potentially, Harsiese's kingship could have posed a serious challenge to the authority of Osorkon, however, when Harsiese died in 860 BC, Osorkon II acted to ensure that no king would replace Harsiese. He appointed his son, Nimlot C, as the high priest of Amun at Thebes, which would have been the source for a successor to Harsiese. This consolidated the king's authority over Upper Egypt and thereafter, Osorkon II ruled over a united Egypt. Osorkon II's reign was a time of prosperity for Egypt and large-scale monumental building ensued.

Foreign policy and monumental program

Despite his astuteness in dealings with matters at home, Osorkon II was forced to be aggressive on the international scene. The growing power of Assyria was accompanied with increased meddling in the affairs of Israel and Syria – territories well within Egypt's sphere of influence.

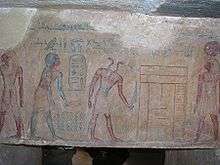

Osorkon II devoted considerable resources into his building projects by adding to the temple of Bastet at Bubastis,[2] which featured a substantial new hall decorated with scenes depicting his Sed festival and images of his queen, Karomama. Monumental construction during his reign also was performed at Thebes, Memphis, Tanis, and Leontopolis. Osorkon II also built Temple J at Karnak during the final years of his reign and it was decorated by his high priest, Takelot F (the future king, Takelot II). Takelot F was the son of the deceased high priest Nimlot C and, thus, Osorkon II's grandson.

Now, all of Osorkon II's sizeable stone statues are known to be re-used works of earlier periods that merely were re-inscribed for Osorkon II, including the famous "Cairo-Philadelphia statue of Osorkon II".[3] Osorkon II was the last great Twenty-second Dynasty king of Tanis, ruling Egypt from the Delta to Upper Egypt. His successor, Shoshenq III, lost the effective control of Middle and Upper Egypt that Osorkon II had assembled into a united Egypt.

Many officials may be dated to the reign of Osorkon II. Ankhkherednefer was inspector of the palace, Paanmeny probably was his chief physician, Djeddjehutyiuefankh was the fourth prophet of Amun,[4] and Bakenkhons was another prophet of Amun during his reign.[5]

Reign length

Approximately 837 BC, Osorkon II died and he was buried in Tomb NRT I at Tanis. Currently, he is believed to have reigned for more than 30 years, rather than just 25 years as had been interpreted earlier. The celebration of his first Sed Jubilee previously was thought to have occurred in his Year 22, but the Heb Sed date in his Great Temple of Bubastis is damaged and also may be read as Year 30, as Edward Wente notes.[6] The fact that this king's own grandson, Takelot F, served him as High Priest of Amun at Thebes–as the inscribed walls of Temple J prove – supports the hypothesis of a longer reign for Osorkon II.

Recently, it has been demonstrated that Nile Level Text 14 (dated to Year 29 of an Usimare Setepenamun) belongs to Osorkon II on palaeographical grounds.[7] This finding suggests that Osorkon II likely did celebrate his first Heb Sed in his Year 30 as was traditionally the case with other Libyan era kings, such as Shoshenq III and Shoshenq V. In addition, a Year 22 Stela from his reign preserves no mention of any Heb Sed celebrations in that year, as would be expected (see Von Beckerath, 'infra').

While Osorkon II's precise reign length is unknown, some Egyptologists, such as Jürgen von Beckerath – in his 1997 book Chronology of the Egyptian Pharaohs[8] – and Aidan Dodson have suggested a range of between 38 and 39 years.[9] However, these much higher figures are not verified by the current monumental evidence. Gerard Broekman gives Osorkon II a slightly shorter reign of 34 years.[10] English Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen, in a 2006 Agypten und Levante article, now accepts that if Nile Level Text 14 is correctly attributed to Year 29 of Osorkon II, then the reference to Osorkon's Sed Festival jubilee should be amended from Year 22 to Year 30.[11] Kitchen suggests that Osorkon II would have died shortly afterward, in his Year 31.[12]

Marriages and children

Osorkon II is known to have had at least four wives:

- Queen Karomama is the best known of Osorkon's wives. Karomama was the mother of at least two sons and three daughters:[13][14]

- Isetemkheb is known to be the mother of a daughter named, Tjesbastperu, who was married to the High Priest of Ptah Takelot B.[13]

- Djedmutesakh IV was the mother of the High Priest of Amun Nimlot C.[13] Nimlot C was a son of Osorkon II and the father of Takelot F, who would become Takelot II.

- Mutemhat was another of his wives.

Other children of record included:

- Prince Shoshenq D was High Priest of Ptah

- Prince Hornakht was the High Priest of Amun in Tanis[15] Osorkon II appointed Hornakht as the chief priest of Amun at Tanis to strengthen his authority in Lower Egypt; however, this was clearly a political move since Hornakht died prematurely before the age of ten.[16]

- Princess Tashakheper may have served as God's Wife of Amun during the reign of Takelot III

- Princess Karomama C, who may be identical to Karomama Meritmut, a God's Wife of Amun

- Princess Taiirmer

Other possible children attributed to Osorkon II include his successor Shoshenq III and the King's Daughter Tentsepeh (D), the wife of General Ptahudjankhef, who was a son of Nimlot C and hence, a grandson of Osorkon II.[13]

Successor

David Aston has argued in a JEA 75 (1989) paper that Osorkon II was succeeded by Shoshenq III at Tanis rather than Takelot II Si-Ese as Kitchen presumed because none of Takelot II's monuments have been found in Lower Egypt where other genuine Tanite kings, such as Osorkon II, Shoshenq III, and even the short-lived Pami (at 6-7 years) are attested on donation stelas, temple walls, and annal documents.[17] Other Egyptologists, such as Gerard Broekman, Karl Jansen-Winkeln, Aidan Dodson, and Jürgen von Beckerath have endorsed this position as well. Von Beckerath also identifies Shoshenq III as the immediate successor of Osorkon II and places Takelot II as a separate king in Upper Egypt.[18] Gerard Broekman writes in a recent 2005 GM article that, "in light of the monumental and genealogical evidence", Aston's chronology for the position of the twenty-second dynasty kings "is highly preferable" to Kitchen's chronology.[19] The only documents that mention a king Takelot in Lower Egypt, such as a royal tomb at Tanis, a Year 9 donation stela from Bubastis, and a heart scarab featuring the nomen 'Takelot Meryamun' — now have been attributed exclusively to king Takelot I by Egyptologists today, including Kitchen.[20]

The English Egyptologist Aidan Dodson, in his book The Canopic Equipment of the Kings of Egypt, observes that Shoshenq III built "a dividing wall, with a double scene showing Osorkon II" and him "each adoring an unnamed deity" in the antechamber of Osorkon II's tomb.[21] Dodson concludes that while one may argue Shoshenq III erected the wall to hide Osorkon II's sarcophagus, it made no sense for Shoshenq to create such an elaborate relief if Takelot II really had intervened between him and Osorkon II at Tanis for 25 years, unless Shoshenq III was Osorkon II's immediate successor. Shoshenq III must, hence, have wished to associate himself with his predecessor – Osorkon II.[22] Consequently, the case for establishing Takelot II as a Twenty-second Dynasty king and successor to Osorkon II disappears, as Dodson writes. Takelot II instead founded the twenty-third dynasty of Egypt and ruled a divided Egypt by administering Middle and Upper Egypt.

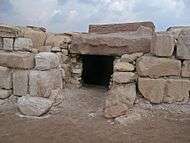

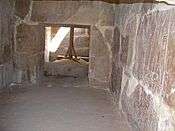

Tomb

The French excavator Pierre Montet discovered Osorkon II's plundered royal tomb at Tanis on February 27, 1939. It revealed that Osorkon II was buried in a massive granite sarcophagus with a lid carved from a Ramesside-era statue. Only some fragments of a hawk-headed coffin and canopic jars remained in the robbed tomb to identify him.[23] While the tomb had been looted in antiquity, what jewellery that remained "was of such high quality that existing conceptions of the wealth of the northern Twenty-first and Twenty-second dynasties had to be revised."[24]

References

- Osorkon (II) Usermaatre, Digital Egypt for Universities.

- Mohamed I. Bakr and Helmut Brandl, "Bubastis and the Temple of Bastet", in: M.I. Bakr, H. Brandl, and F. Kalloniatis (eds.), Egyptian Antiquities from Kufur Nigm and Bubastis. M.i.N. (Museums in the Nile Delta) 1, Cairo/Berlin 2010, pp. 27-36

- H. Sourouzian, "Seti I, not Osorkon II. A new join to the statue from Tanis, CG 1040 in the Cairo Museum", in: O. El-Aguizy – M. Sherif Ali (eds), Echoes of Eternity. Studies presented to Gaballa Aly Gaballa, Philippika 35, Wiesbaden 2010, pp. 97–105; Helmut Brandl, Bemerkungen zur Datierung von libyerzeitlichen Statuen aufgrund stilistischer Kriterien, in: G. P. F. Broekman, R. J. Demarée, O. E. Kaper (eds.), The Libyan Period in Egypt. Egyptologische Uitgaven 23, Leiden 2008, pp. 60-66, pl. I-II. (https://www.academia.edu/8241577/Bemerkungen_zur_Datierung_von_libyerzeitlichen_Statuen_aufgrund_stilistischer_Kriterien

- Statue, Cairo CG 42206, 42207

- Cairo CG 42213

- Edward Wente, Review of Kenneth Kitchen's The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt c.1100-650 BC, JNES 35(1976), pp.275-278

- Gerard Broekman, "The Nile Level Records of the Twenty-Second and Twenty-Third Dynasties in Karnak," JEA 88(2002), pp.174-178

- Jürgen von Beckerath, Chronologie des Pharaonischen Ägypten, MAS:Philipp von Zabern, (1997), p.98 & p.191

- Aidan Dodson, A new King Shoshenq confirmed?, GM 137(1993), p.58

- Gerard Broekman, 'The Reign of Takeloth II, a Controversial Matter,' GM 205(2005), pp.31 & 33

- Kenneth Kitchen, Agypten und Levante 16 (2006), p.299 point No.7

- Kitchen, Agypten und Levante 16 (2006), p.301 section 16

- Aidan Dodson & Dyan Hilton: The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson, 2004, ISBN 0-500-05128-3

- Kitchen, The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100–650 BC). 3rd ed. Warminster: Aris & Phillips Limited. 1996

- .Nos ancêtres de l'Antiquité, 1991. Christian Settipani, p.153 and 166

- Nicolas Grimal, A History of Ancient Egypt, Blackwell Books, 1992. p.325

- Aston, pp.139-153

- Jürgen von Beckerath, "Chronologie des Pharaonischen Ägypten," MÄS 46 (Philipp von Zabern), Mainz: 1997. p.94

- Gerard Broekman, 'The Reign of Takeloth II, a Controversial Matter,' GM 205(2005), pp.31

- K.A. Kitchen, in the introduction to his 3rd 1996 edition of "The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (c.1100-650 BC)," Aris & Phillips Ltd. pp.xxxii-xxxiii

- Aidan Dodson, "The Canopic Equipment of the Kings of Egypt," (Kegan Paul Intl: 1994), p.95

- Dodson, The Canopic Equipment of the Kings of Egypt, p.95

- "San el-Hagar". Archived from the original on 2009-01-20. Retrieved 2006-02-18.

- Bob Brier, Egyptian Mummies: Unravelling the Secrets of an Ancient Art, William Morrow & Company Inc., New York, 1994. p.144

Further reading

- Bernard V. Bothmer, The Philadelphia-Cairo Statue of Osorkon II, JEA 46 (1960), 3-11.

- M.G. Daressy, une Stèle de Mit Yaich, ASAE 22 (1922), 77.

- Helen K. Jaquet-Gordon, The Inscriptions on the Philadelphia-Cairo Statue of Osorkon II, JEA 46 (1960), 12-23.